Aleshina individual and family psychological counseling. Aleshina Yu.E Individual and family psychological counseling Aleshina yu individual family psychological counseling

Julia Aleshina

individual

and family

psychological

Consulting

Moscow

Independent firm "Class"

Aleshina Yu.E.

A 51 Individual and family psychological counseling. - Ed. 2nd. - M.: Independent firm "Class", 1999. - 208 p. - (Library of psychology and psychotherapy).

ISBN 5-86375-111-8

Books like this one are often read with a pencil in hand, marking the most important steps in the work. Here is a short and sensible practical guide that describes the basic techniques and techniques of psychological counseling and strategies for working with different types of clients. All illustrative examples from practice reflect the Russian psychological context, and this increases the value of the book.

For students and novice consultants, it will certainly become a desktop one, and it will also help experienced practicing psychologists more than once in organizing and conducting counseling.

Editor-in-Chief and Series Publisher L.M. Crawl

Scientific Advisor Series E.L. Mikhailova

ISBN 5-86375-111-8 (RF)

© 1993, Yu.E. Alyoshin

© 1999, Independent firm “Class”, edition, design

© 1999, E.A. Purtova, foreword

© 1999, L.M. Kroll, foreword

© 1999, V.E. Korolev, cover

www.kroll.igisp.ru

Buy the book "At the KROL"

The exclusive right to publish in Russian belongs to the publishing house “Independent Firm “Class”. The release of a work or its fragments without the permission of the publisher is considered illegal and is punishable by law.

praise predictability

Yulia Aleshina did a lot to make us feel much more comfortable in the space of psychological counseling today. She was among those who, ten years ago, created the first professional association - the Association of Practitioner Psychologists, through whose efforts our profession ceased to look like an exotic plant in the dense taiga. In her book, counseling is presented not as a mystical sacrament, but as an ordinary craft. This is a book-textbook, where each action of a consultant is described in steps: how to get acquainted, how to behave with those who resist, how to explain to clients what counseling is... Such a step-by-step (and per-minute!) description of the rules removes the anxiety of uncertainty and fear of insolvency among beginners, gives hope that if you follow them, then everything will work out as it should. And the truth is, it works. And now, when there is already experience, these rules are somewhere inside, like a metro map. And from station A to station B there are many lines-roads, but the transfer points are still the same: establishing contact, reformulating the request, analyzing typical situations ...

Rereading this book, one is surprised to discover how much has changed in our profession in the six years that have passed since its first publication. Now no one doubts the need for supervisory support, which the author strongly reminds of in each chapter. And it is already obvious to everyone that the "purity" of advisory work is also ensured by the consultant's client experience, his personal elaboration. But six years ago, to recommend to practicing psychologists personal psychotherapy, which was nowhere to be obtained, meant adding another impossibility to this already hardly possible occupation. Note that psychologists still do not have the legal right to engage in psychotherapy. And in those years, desperate courage was required to enter a new field of practice.

During this time, our clients have also changed: now it is rarely necessary for anyone to explain what counseling is, more often they come with an understanding of the need for long-term work, they are more ready to consider themselves as the source of the problem. Yes, and the typical problems are not quite the same. But whatever the client's request, no matter how it changes over time, the counseling techniques described by the author remain a well-functioning tool. And if for beginners it is the techniques that make up the unconditional dignity of the book, then with the acquisition of experience you begin to see generalized counseling strategies, like any psychotherapeutic practice: transferring responsibility for your life to the client, helping to accept their feelings, developing more adequate ways of behavior ... And about this is also stated in the book.

It will be useful for a long time to come - as a primer for those who get acquainted with counseling, a fascinating lesson for those interested in psychology, a systematic guide for those who like to put everything in order.

The significance of the gender category for understanding the psychological characteristics of an individual and the specifics of his life path has been proven by numerous experimental and theoretical studies. However, in Soviet psychology, the problem of gender is presented so poorly that this gave rise to I.S. Kohn call her "genderless". Only in last years the situation began to change: a number of review and empirical works on the problem of sexual socialization were published. One of the steps in this direction is the research project of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR "Socio-psychological problems of socialization and assimilation of sex roles", dedicated to the analysis of the peculiarities of the position of men and women in the USSR, the factors of success in sex role socialization and functioning. This article is summary theoretical concept of this study.

The results of the work carried out over the past 15 years provide more and more evidence in favor of the sociocultural determination of gender differences. If until recently it was considered firmly established that there are three types of sex differences that do not depend on environmental and upbringing factors (spatial imagination, mathematical abilities, verbal intelligence), then the latest data obtained already in the 80s indicate that even there are no biologically determined differences in these parameters.

At the same time in Everyday life we are constantly confronted in one form or another with differences between the sexes, which are in many ways a reflection of some implicit agreement regarding the possibility of displaying certain qualities. In the most generalized form, they are represented by stereotypes of masculinity and femininity. The man is strong, independent, active, aggressive, rational, focused on individual achievements, instrumental; a woman is weak, dependent, passive, soft, emotional, oriented towards others, expressive, etc. Sex-role stereotypes existing in society have a great influence on the process of socialization of children, largely determining its direction. Based on their ideas about the qualities that are characteristic of men and women, parents (and other educators), often without realizing it themselves, encourage children to show precisely these sex-specific traits.

Interestingly, this behavior is not a response to real differences between children. This is demonstrated, in particular, by experiments with the fictitious sex of the child. So, for example, regardless of the real gender, if the baby was presented to observers as a boy, his behavior was described as more active, fearless and cheerful than when he was considered a girl. Wherein negative emotions in the "boy" they were perceived as manifestations of anger, and in the "girl" - fear. Thus, the social world from the very beginning turns to the boy and the girl from different sides.

Let us consider in more detail the specifics of the socialization situation for each sex. No matter how one describes the process of assimilation of a sex role in various psychological orientations, there is no doubt the influence exerted on the child by people who serve him as a model of sex-specific behavior and a source of information about the sex role. In this sense, the boy is in a much less favorable situation than the girl. So, the mother traditionally spends much more time with a small child. The child sees the father a little less often, not in such significant situations, therefore, usually in the eyes of the baby, he is a less attractive object. In this regard, both for a girl and for a boy, in almost any culture, identification with the mother, i.e., feminine, is primary. Moreover, the very basic orientations of the child in relation to the world are feminine in nature, for they include such traditionally feminine features as dependence, subordination, passivity, etc.

Thus, in terms of the formation of gender identity, the boy will have to solve a more difficult task: to change the initial female identification to a male one along the lines of significant adult men and cultural standards of masculinity. However, the solution of this problem is complicated by the fact that almost everyone with whom the child comes into close contact, especially in modern Russian society (educators kindergarten, doctors, teachers), women. Not surprisingly, boys end up being much less aware of male gender role behavior than female gender.

At the same time, the prevalence of traditional ideas about the hierarchical relationship of sex roles leads to the fact that, compared with girls, boys experience stronger social pressure in the direction of the formation of sex-specific behavior. Attention begins to be paid to this earlier, the value of the corresponding gender role and the danger of evading it are more emphasized, and the male stereotypes themselves are much more narrow and categorical.

In combination with the lack of role models, such pressure leads to the fact that the boy is forced to build his gender identity mainly on a negative basis: not to be like girls, not to participate in female activities, etc. At the same time, in our country, the child has relatively there are few opportunities for actually masculine manifestations (for example, aggression, independence, motor activity, etc.), since adults treat them rather ambivalently, as a source of anxiety. (Evidence of the prevalence of this attitude is psychotherapeutic practice, in which hyperactivity and aggressiveness, regardless of the sex of the child, are much more common reasons for parents to seek help than lethargy and inhibition.) Therefore, stimulation from adults is also predominantly negative: not encouraging "male" manifestations, but punishment for "non-male". As an example, we can cite a typical parental statement “it’s shameful to cry, you’re a boy”, and male ways of responding to insult are either not offered or depreciated (“you can’t fight”). Thus, the child is required to do something that is not clear enough for him, and based on reasons that he does not understand, with the help of threats and the anger of those who are close to him. This state of affairs leads to an increase in anxiety, which often manifests itself in excessive efforts to be masculine and panic fear do something feminine. As a result, male identity is formed primarily as a result of identifying oneself with a certain status position, or a social myth “what a man should be like”. Not surprisingly, the identity created on this basis is diffuse, easily vulnerable and at the same time very rigid.

The social pressure on the boy especially intensifies with the transition to the public system of education - a preschool institution or school, since, on the one hand, teachers and educators are distinguished by a significantly higher traditionalism, and on the other hand, the parents themselves, preparing the child for a meeting with a new world. him by the situation of social assessment, increase the rigidity of their normative standards.

All this leads to the fact that the moment comes in the socialization of the boy, when he needs to “disown” the “female world”, his values and create his own, male. The transition to this stage usually begins at the age of 8-12, when the first children's companies arise, close interpersonal relationships with peers are formed, on which the boy can henceforth rely as a source of male role models and a sphere for the realization of masculine qualities. This process, called the male protest, is characterized by a vivid negativism towards girls and the formation of a special “male”, emphatically rude and harsh style of communication.

This exaggerated idea of masculinity, focused on the most striking features of the brutal male image, softens somewhat and becomes more egalitarian only in the future. According to Western data, this happens by the beginning of adolescence, when the boy manages to defend his identification from the pressure of the female world. However, the lack of opportunities for the formation and manifestation of masculinity, which is characteristic of our country, suggests that in our country this process is even more complex and dramatic and ends much later. Thus, the changes in everyday life that have taken place over the past decades have led to the fact that there are almost no “manly affairs” left, and the boy does not have the opportunity to prove himself a real man in the family, where, first of all, the child learns the sex role. Although such changes in the domestic sphere have occurred in almost all developed countries and are even less pronounced in our country, the peculiarity of the situation is that it is no less difficult for a boy to express himself outside the family. An intense ban on negative manifestations of masculinity (smoking, drinking, fighting) is combined in our society with a negative attitude towards activity, competitiveness, and various forms of aggression. (It should be noted that the tolerance of parents and caregivers to children's aggressiveness varies greatly in different cultures; for example, according to cross-cultural studies, American parents are 8-11 times more tolerant of aggression than in all other societies studied.) At the same time, social channels for the manifestation of aggression in acceptable forms (sports, games) we clearly do not have enough. The situation is little better with other “socialized” types of masculine activity of children and adolescents (technical construction, hobbies, independent participation in professional activities, etc.), which could become a powerful source for the formation of a positive male identity.

A particularly sad phenomenon in terms of the formation of models of masculinity is the school. Thus, a study conducted by A.S. Volovich, showed that among those senior students who best meet school requirements, the vast majority (85%) are girls. Yes, and the young men who fell into this category differed from others rather in traditionally feminine qualities (exemplary behavior, perseverance, diligence, etc.), while the qualities that characterize intelligence or social activity were practically not represented.

In this regard, it is interesting to recall the features of the Soviet pedagogical system identified by Yu. Bronfenbrenner, which distinguish it from that adopted in the United States: assessment of the activities and personality of students according to the contribution they made to the overall result; using public criticism or praise as methods of influence; recognition of the most important duty of each to help other members of the team. Thus, primarily feminine qualities are encouraged: orientation towards others, affiliative and expressive tendencies. Apparently, such a difference in the possibilities for the manifestation of masculinity was initially due to the different orientation of education. If the most common notion of parenting goals in the United States is strongly masculine—“in American culture, children are encouraged to be independent and self-reliant,” then for Soviet Union this orientation is rather feminine: "the child must be a worthy member of the team."

What is the big picture? Constant and persistent demands: “be a man,” “you don’t behave like a man,” “you’re a boy,” are combined with the lack of opportunities to form and display a masculine type of behavior in any of the spheres of life. It can be assumed that such a situation leads, first of all, to passivity, refusal of activities that are proposed to be performed in a feminine form and on an equal basis with girls. It is better to be passive than "not a man", because at the same time it remains possible to ascribe to oneself a whole set of masculine qualities, believing that they could manifest themselves in a different, more suitable situation.

There is another way of looking for opportunities to express masculinity - this time not in dreams, but on an extra-social basis. First of all, it is striking that most of the members of the informal associations of adolescents that have recently appeared in large numbers in our country are boys, and masculinity is emphasized both in appearance (leather, metal) and in basic values (the cult of risk, strength) and the way of spending free time (fights, strength exercises, motorcycle racing, etc.). Thus, deviant behavior acts as an additional channel for the assimilation of the male sexual role, since the opportunities provided by society in this regard are small.

Having discussed the difficulties of male socialization, let us analyze the features of the assimilation of the female sex role.

A newborn girl is "lucky", of course, more. From the very beginning, she has a role model corresponding to her sex, so she will not have to give up her primary identification with her mother in the future. Doctors, kindergarten teachers, teachers will only help her form an adequate image of herself as a woman. The absence of a rigid stereotype of a “real woman” in culture, a variety of ideas about truly feminine qualities also facilitate the formation of a gender role identity, giving the girl ample opportunity to conform to the stereotype, remaining herself. At the same time, as modern research shows, the relationship between a girl and her mother already has its own specific problems that have serious consequences for her sex-role socialization.

One of the most important tasks in the formation of a child's personality is the destruction of the primary symbiotic dyad "mother - child", in which the child does not perceive himself and in fact does not exist as a separate subject. Drawing boundaries between herself and her mother is especially relevant for a girl, since, due to the specifics of her own experience (being a woman, a daughter, etc.), a mother tends to perceive her daughter as her continuation more than her son. This manifests itself in many small details: closer physical contact with the baby girl, greater restriction of motor activity, frequent attribution of any needs to the daughter based on identification with her. As a result, the girl's relationship with her mother becomes not only more symbiotic and intense than that of the boy, it is also more charged with ambivalence. This pushes the girl to look for another person who could also give her a sense of security and confidence, but at the same time would not be fraught with the threat of dissolving the still weak child's self in the familiar environment.

Very soon it turns out that in addition to the mother who is always nearby, there is one more person - the father, the importance and significance of which is emphasized in every possible way by others. Moreover, most often it is this “important” person who pays relatively little attention to the girl. The desire to attract him can be associated with a number of negative experiences: firstly, the feeling of being secondary in comparison with the attractive world of men; secondly, the need to somehow prove oneself, demonstrate, in order to get attention. Somewhat coarsening, we can say that it is the intertwining of these two tendencies that further determines the specifics of the sex-role socialization of the girl. Thus, for example, empirical data obtained in the West indicate that the behavior of preschool daughters is twice as likely to be limited by parental intervention than the behavior of sons. Naturally, such a situation also contributes to the formation of a feeling of insignificance in the girl.

This experience is further exacerbated by the influence of traditional cultural patterns. Numerous studies of literature and television programs for children have shown almost everywhere that the most important characteristic of the image of a woman offered in them is its invisibility: women are much less often represented in the main roles, titles, pictures, their activities are less interesting and are not socially rewarded, most often comes down to helping the male protagonist. Based on these data, it is not surprising that from the age of 5-6 years onwards, the number of girls who say that they would like to be boys and play boyish games significantly exceeds the number of boys who express cross-sexual preferences.

In Soviet works for children, along with a similar image of a woman, there is another one, an example of which is “mother-cook” or “mother-policeman” from S. Mikhalkov’s poem: after listing different professions, the author considers it necessary to emphasize: “different mothers are needed”, explicitly assuming that if children are not taught, they will be guided in the “assessment” of mothers by their professional status. Thus, from childhood, a child learns the need to combine a female role with a professional one, and the question of their hierarchy remains open. At the same time, male and professional roles are presented as identical, since no other male manifestations are practically described anywhere. As a result, the female role looks not only secondary, but also more difficult, with a double load. Thus, if it is easier for a girl to achieve gender role identity than for a boy, the formation of gender role preferences (a higher appreciation of everything feminine) turns out to be significantly more difficult. However, a positive solution to this problem can be found based on previous experience in which she has already succeeded (if she succeeded, the nature of her relationship with her father in childhood plays a huge role here) to achieve recognition by showing her own activity. Wherein great importance has the fact that the girl has many opportunities for the manifestation of women's activities and a sufficient number of patterns that she can follow.

So, for example, a model of socialization that is quite successful in this regard takes shape in a family where, doing everyday women's affairs (cleaning, cooking, washing, etc.), without which it is impossible to imagine the life of any Soviet family, the girl learns to responsibility and activity. To a large extent, this is also facilitated by the school, where the main emphasis, as we have already written above, is placed on the development of traditionally female qualities. There are far more girls involved in social work (i.e., showing additional activity) in our schools than boys. This is natural, since the social activity carried out within the framework of the school most often implies the establishment and maintenance of extensive contacts with other people (classmates, patrons, etc.), which corresponds to the female stereotype of behavior. At the same time, this situation leads to the formation of differences between the sexes that do not correspond to the traditional ones. So, in the study of E. V. Novikova, it was shown that high school students are more responsible and active than their classmates.

Such a violation of the sexual stereotype is not accidental and has deep roots in the characteristics of our culture. The proclaimed focus on social equality of men and women leads to the fact that they are being prepared for a very similar life path: regardless of gender, everyone needs to get an education and work, the family for a woman acts only as an “additional” sphere of realization. At the same time, traditional views on gender relations as hierarchical remain very influential in our society, therefore, both the surrounding people and various circumstances (the preferred admission of boys to higher educational establishments, to work, etc.) are constantly reminded of the advantages of men. This situation stimulates the development of masculine qualities in women: competitiveness, striving for dominance, and overactivity.

Thus, sex-role socialization in its modern form leads to paradoxical results: boys are, as it were, pushed into passivity or extra-social activity, while girls, on the contrary, are pushed into hyperactivity and dominance. At the same time, they will have to live in a society largely oriented towards traditional gender role standards.

Let us briefly dwell on what consequences this contradiction can lead to in various spheres of life, namely in the family and professional activities.

The beginning of the formation of any family is a process of courtship. In our culture, it develops quite traditionally - a man is active, expresses his feelings, tries to win attention; while the woman is relatively passive and feminine. Since the traditional form of courtship is one of the few forms of a double standard that directly "benefits" a woman, it is relatively easy for her to assume a dependent position. After marriage, the distribution of roles and responsibilities in the family also begins to take shape in a very traditional way: the wife, striving to be “good” and as feminine as during courtship, takes on most of the responsibilities. However, in this situation, the traditional double standard turns out to be inconvenient. Unequal participation in family affairs(especially noticeable in connection with the acquired idea of gender equality and truly equal involvement in professional activities) ceases to suit a woman rather quickly. And although such a distribution of roles is objectively beneficial for the husband (it leaves more time and more freedom), at the same time it once again emphasizes the active position of the woman and the passivity of the position of the man, which can cause psychological discomfort for him as well.

This situation is even more aggravated when the first-born is born in the family. Studies, both Soviet and foreign, show that after this, the satisfaction with the marriage of the spouses begins to decrease, since the birth of a child leads to a significant traditionalization of the positions of both spouses, when the wife performs purely feminine tasks and duties related to the family and home, and the husband - - male, associated primarily with work. While the child is very young, such a distribution of responsibilities is relatively justified in the eyes of both spouses. The decrease in satisfaction with marriage reaches a maximum by the time the child is 3-4 years old and caring for him, even from the point of view of everyday consciousness, no longer requires any special feminine qualities. During this period, parental leave ends and a woman has a double burden: regardless of her desire, she is forced to go to work and at the same time continues to perform the vast majority of household chores. Naturally, this situation does not suit women, besides, going to work strengthens their masculine orientation, which also contributes to the growth of activity and the need to change the family situation.

In essence, the only way to solve this problem is the active involvement of the husband in the affairs of the family. But such a radical change in his position is very difficult due to a number of factors: previous socialization, which did not prepare the boy for active participation in family affairs; the distribution of roles and responsibilities already established in the family, the inertia of which is not easy to overcome; and finally, the social situation as a whole, where work (and, above all, the work of men) is more valued and, consequently, it is difficult for a man to give up his “social position” and reorient himself towards his family. It is no coincidence, as counseling practice shows, that another variant is more common: the husband, fleeing from the pressure of his wife, is increasingly immersed in a state of passivity1, while the wife becomes more and more demanding and directive. As a result, an active wife and a passive husband turn out to be side by side in the family, which, naturally, in a situation where most women and men are oriented towards traditional patterns of behavior, does not contribute to the growth of family well-being.

Turning to the analysis of the manifestations of the sex-role characteristics of a person in professional activity, it is important to remember that the nature of work, and, consequently, the qualities of an employee are largely determined by the economic and social characteristics of society. In this regard, data on the difference in the qualities required for a worker in a market and directive-centralized economy are interesting: in the first case, this is an orientation, primarily on individual responsibility, activity, initiative, rationalism, etc., and in the second, on collective responsibility. , diligence, instrumental attitude to work, conservatism, etc. It would not be an exaggeration to say that such an opposition surprisingly resembles the dichotomy of male and female principles. This situation leads to a paradoxical conclusion: in the conditions of a directive-centralized economy, it turns out to be difficult to display masculine traits in such a traditionally male area as work, which naturally reduces both the motivation for activity and satisfaction with it, and also contributes to further avoidance of social activity. It would seem that in this situation, women are in a more advantageous position. But is it?

Traditionalism and the effects of the "double standard" characteristic of our society have already been discussed above. Undoubtedly, the influence of these factors on the professional activities of women is quite large, if only because the overwhelming majority of representatives of the administrative apparatus are men, and this despite the fact that 51.4% of workers in our country are women. But there are a few interesting points related to the work of women in our country, which I would like to say especially.

According to many foreign authors, the qualities of female workers should be a continuation of traditional feminine features. There is evidence that women are most attracted to work by the opportunity to help people. Thus, when analyzing the main preferences of working women in the United States, it turned out that in their profession they tend to continue typical family activities: raising children (pedagogy), caring for others (medicine), helping a husband (secretary work), cooking (cooking) - - and manifest themselves in work in traditional feminine roles - mothers, wives, housewives. In addition, if men are more oriented towards social activity and are more dynamic, then women prefer armchair, chamber, not very dynamic work.

Looking through this list, one cannot fail to notice that the emphasis on the prestige of professions in our country is arranged in such a way that all the selected professions are, on the one hand, not prestigious, and on the other, low-paid (this is especially noticeable for professions related to service labor) . Thus, the current situation deliberately deprives feminine women of the possibility of high job satisfaction.

There is another important factor that undoubtedly influences the attitude of women towards their work. Thus, data obtained by a number of authors indicate that women who are forced to work to support themselves and their families are significantly less satisfied with their professional activities than their counterparts engaged in similar work, receiving the same or even less wages, but working exclusively at will (the financial situation of the family allows them not to work at all). In addition, if a woman may not work, but is engaged in professional activities, as this "increases her emotional background and self-esteem", she is more successful and efficient.

What are the motives of women's work in our society? According to some data, 40% of the women surveyed work only for the sake of money. The second most popular motive for work is the desire to be in a team, and only the third is interest in the content of professional activity.

Thus, the labor market in our country practically does not provide opportunities for the realization of either a man or a woman of gender identity, orienting people employed in production to some average, asexual type of worker.

In this article, we have considered only two examples of the negative impact of the current practice of sex-role socialization on the self-realization of the individual in our culture. Undoubtedly, their number can be multiplied. However, it seems to us that this far from complete list already indicates the urgent need for the “rehabilitation” of the category of sex, both in the practical recommendations of psychologists and in research itself, since the cultural specificity in this area is large enough to deprive us of the opportunity to directly appeal to foreign data.

Aleshina Yu.E.

A 51 Individual and family psychological counseling.- Ed. 2nd. - M.: Independent firm "Class", 1999. - 208 p. - (Library of psychology and psychotherapy).

ISBN 5-86375-111-8

Books like this one are often read with a pencil in hand, marking the most important steps in the work. Here is a short and sensible practical guide that describes the basic techniques and techniques of psychological counseling and strategies for working with different types of clients. All illustrative examples from practice reflect the Russian psychological context, and this increases the value of the book.

For students and novice consultants, it will certainly become a desktop one, and it will also help experienced practicing psychologists more than once in organizing and conducting counseling.

Editor-in-Chief and Series Publisher L.M. Crawl Scientific Advisor Series E.L. Mikhailova

The exclusive right to publish in Russian belongs to the publishing house Nezavisimaya Firma Klass. The release of a work or its fragments without the permission of the publisher is considered illegal and punishable by law.

Individual copies of the books in the series can be purchased in Moscow stores:

House of the book "Arbat", Trading houses "Biblio-Globus" and "Young Guard", stores number 47 "Medical Book" and "The Way to Yourself", book salon "KSP +".

Praise for predictability. Foreword by E.A. Purtovoy 3

From the publisher with nostalgia. Foreword by L.M. rabbit 4

Introduction 5

1. General idea of psychological counseling 6

2. The conversation process 13

3. Technology of conversation 23

4. Counseling parents about difficulties in relationships with adult children 33

5. Communication difficulties 42

7. Couple Counseling 55

8. Single Spouse Counseling 66

9. Experiencing separation from a partner 73

Conclusion 83

Literature 84

PRAISE FOR PREDICTABILITY

Yulia Aleshina did a lot to make us feel much more comfortable in the space of psychological counseling today. She was among those who, ten years ago, created the first professional association - the Association of Practitioner Psychologists, through whose efforts our profession ceased to look like an exotic plant in the dense taiga. In her book, counseling is presented not as a mystical sacrament, but as an ordinary craft. This is a book-textbook, where each action of a consultant is described in steps: how to get acquainted, how to behave with those who resist, how to explain to clients what counseling is... Such a step-by-step (and per-minute!) description of the rules removes the anxiety of uncertainty and fear of insolvency among beginners, gives hope that if you follow them, then everything will work out as it should. And the truth is, it works. And now, when there is already experience, these rules are somewhere inside, like a metro map. And from station A to station B there are many lines-roads, but the transfer points are still the same: establishing contact, reformulating the request, analyzing typical situations ...

Rereading this book, one is surprised to discover how much has changed in our profession in the six years that have passed since its first publication. Now no one doubts the need for supervisory support, which the author strongly reminds of in each chapter. And it is already obvious to everyone that the "purity" of advisory work is also ensured by the consultant's client experience, his personal elaboration. But six years ago, to recommend to practicing psychologists personal psychotherapy, which was nowhere to be obtained, meant adding another impossibility to this already hardly possible occupation. Note that psychologists still do not have the legal right to engage in psychotherapy. And in those years, desperate courage was required to enter a new field of practice.

During this time, our clients have also changed: now it is rarely necessary for anyone to explain what counseling is, more often they come with an understanding of the need for long-term work, they are more ready to consider themselves as the source of the problem. Yes, and the typical problems are not quite the same. But whatever the client's request, no matter how it changes over time, the counseling techniques described by the author remain a well-functioning tool. And if for beginners it is the techniques that make up the unconditional dignity of the book, then with the acquisition of experience you begin to see generalized counseling strategies, like any psychotherapeutic practice: transferring responsibility for your life to the client, helping to accept their feelings, developing more adequate ways of behavior ... And about this is also stated in the book.

It will be useful for a long time to come - as a primer for those who get acquainted with counseling, a fascinating lesson for those interested in psychology, a systematic guide for those who like to put everything in order.

Elena Purtova

FROM THE PUBLISHER WITH NOSTALGIA

Yulia Aleshina is the person to whom I and many other people - whether they know it or not - owe their organized training according to proven and serious Western standards (what is called "first hand"). If we imagine that we will someday take seriously the history of our professional life and community, then, in high style, it would certainly be worth a monument to it.

The combination of professional qualities, energy, organizational abilities and social competence combined in her into that precious alloy, which is even more clearly visible over time. Now Julia is an established and recognized professional in the American (and international) psychotherapeutic culture.

It is especially pleasing that a book written more than six years ago is so good and timely today. It seems to me that it is one of the decorations of our series, along with the works of the "first persons" of world psychotherapy. This once again proves that the so-called world psychotherapy lives and develops thanks to the efforts of our people.

As a publisher, I really hope that this is not Yulia's last book in Russian.

Leonid Krol

INTRODUCTION

The manual offered to the attention of readers is an attempt to answer many questions that are primarily of concern to novice practicing psychologists and that arise during the conduct of a wide-profile psychocorrectional technique. The book consists of two parts, the first of which is devoted to the problems of organizing and conducting a consultative reception. It analyzes the conversation process, analyzes in detail the special techniques and methods of conducting it. The second part of the book presents an attempt to analyze the most typical cases of people seeking help from a psychologist and general strategies for managing various types clients.

It is necessary to immediately make a reservation that the types of techniques analyzed in the second part are focused on working with adults, with their problems and complaints. Working with children inevitably requires knowledge of children's and developmental psychology, educational psychology, as well as medical and, above all, psychiatric knowledge about the development of children and adolescents, that is, something that goes far beyond the scope of the proposed manual.

The contents of this book can only give the reader an outline, a general guideline for advisory work. Professional use of everything that will be discussed here, in our deep conviction, can only be done by people who, firstly, have a full education in the field of psychology and, secondly, have the opportunity to work at least for some time in supervisory conditions, then there is supervision and analysis by more experienced colleagues.

A psychological diploma is needed not just because non-specialists do not know and do not understand much. During the years of study at the Faculty of Psychology (if it was sufficiently effective), students develop a special worldview. There are many jokes and ironic statements about it, it has certain costs, but from the point of view of psychological counseling, it is important that it is based on the idea of the complexity, inconsistency of the nature of the psyche and human behavior and the absence of any ordinary norms and dogmas, in within which the client can be uniquely evaluated. Such views of a professional psychologist mean not only a certain attitude towards people in general, and, consequently, towards clients, but also the ability to use these views, based on the data of psychological research, on the work of the classics of practical and scientific psychology (Etkind A.M., 1987).

I would also like to briefly dwell on the features of the use of some words in this manual. So, the words "client" and "consultant" are masculine nouns in Russian and it would be more correct to write "client / -ka /", "consultant", he / she, and, accordingly, use the verbs, relating to them, for example, "client / -ka / did / -a /, said / -a /" (similarly - with the words "husband" and "partner"). However, since this would greatly complicate the perception and understanding of the text, then, averting accusations of sexism from myself in advance, I want to apologize that these terms will be used exclusively in the masculine gender, meaning a person in general. In the text, along with the word "consultant", the word "psychologist" is used to refer to a professional who exercises psychological influence; in this paper they are used as synonyms, just as the words "reception", "conversation", "consulting process" are used as synonyms, denoting the consultative impact as such.

Yulia Aleshina did a lot to make us feel much more comfortable in the space of psychological counseling today. She was among those who, ten years ago, created the first professional association - the Association of Practitioner Psychologists, through whose efforts our profession ceased to look like an exotic plant in the dense taiga. In her book, counseling is presented not as a mystical sacrament, but as an ordinary craft. This is a book-textbook, where each action of a consultant is described in steps: how to get acquainted, how to behave with those who resist, how to explain to clients what counseling is... Such a step-by-step (and per-minute!) description of the rules removes the anxiety of uncertainty and fear of insolvency among beginners, gives hope that if you follow them, then everything will work out as it should. And the truth is, it works. And now, when there is already experience, these rules are somewhere inside, like a metro map. And from station A to station B there are many lines-roads, but the transfer points are still the same: establishing contact, reformulating the request, analyzing typical situations ...

Rereading this book, one is surprised to discover how much has changed in our profession in the six years that have passed since its first publication. Now no one doubts the need for supervisory support, which the author strongly reminds of in each chapter. And it is already obvious to everyone that the "purity" of advisory work is also ensured by the consultant's client experience, his personal elaboration. But six years ago, to recommend to practicing psychologists personal psychotherapy, which was nowhere to be obtained, meant adding another impossibility to this already hardly possible occupation. Note that psychologists still do not have the legal right to engage in psychotherapy. And in those years, desperate courage was required to enter a new field of practice.

During this time, our clients have also changed: now it is rarely necessary for anyone to explain what counseling is, more often they come with an understanding of the need for long-term work, they are more ready to consider themselves as the source of the problem. Yes, and the typical problems are not quite the same. But whatever the client's request, no matter how it changes over time, the counseling techniques described by the author remain a well-functioning tool. And if for beginners it is the techniques that make up the unconditional dignity of the book, then with the acquisition of experience you begin to see generalized counseling strategies, like any psychotherapeutic practice: transferring responsibility for your life to the client, helping to accept their feelings, developing more adequate ways of behavior ... And about this is also stated in the book.

Scales: confidence in communication, mutual understanding between spouses, similarity in the views of spouses, common symbols of the family, ease of communication between spouses, psychotherapeutic communication

Purpose of the test

The technique is designed to study the nature of communication between spouses.

Instructions for the test

Choose the answer that best describes your relationship with your spouse.

Test

1. Can you say that you and your wife (husband), as a rule, like the same films, books, performances?

1. Yes;

2. Rather yes than no;

3. Rather no than yes;

4. No.

2. Do you often have a feeling of community, complete mutual understanding in a conversation with your wife (husband)?

1. Very rarely;

2. Quite rare;

3. Quite often;

4. Very often.

3. Do you have favorite phrases, expressions that mean the same thing to both of you, and do you enjoy using them?

1. Yes;

2. Rather yes than no;

3. Rather no than yes;

4. No.

4. Can you predict whether your wife (husband) will like a movie, book, etc.?

1. Yes;

2. Rather yes than no;

3. Rather no than yes;

4. No.

5. Do you think your wife (husband) feels, do you like what she (he) says or does, if you do not directly tell her (him) about it?

1. Almost always;

2. Quite often;

3. Quite rare;

4. Almost never;

6. Do you tell your wife (husband) about your relationships with other people?

1. I tell almost always;

4. I don't tell anything.

7. Do you and your wife (husband) have disagreements about what kind of relationship to maintain with relatives?

1. Yes, they happen almost constantly;

2. Happen quite often;

3. They happen, quite rarely;

4. No, they almost never happen.

8. How well does your wife (husband) understand you?

1. Understands very well;

2. Rather good than bad;

3. Rather bad than good;

4. Doesn't understand at all.

9. Is it possible to say that your wife (husband) feels that you are offended or annoyed by something, but do not want to show it?

1. Yes, it is;

2. Probably so;

3. This is hardly the case;

4. No, it's not.

10. Do you think your wife (husband) tells you about his failures and mistakes?

1. Tells almost always;

2. Tells often enough;

3. Tells rather rarely;

4. Almost never tells.

11. Does it happen that a certain word or object evokes the same memory in both of you?

1. Very rarely;

2. Quite rare;

3. Quite often;

4. Very often.

12. When you are in trouble, in a bad mood, does it get easier for you from communicating with your wife (husband)?

1. Almost always;

2. Quite often;

3. Quite rare;

4. Almost never.

13. Do you think there are topics on which it is difficult and unpleasant for a wife (husband) to talk to you?

1. There are a lot of such topics;

2. There are quite a few of them;

3. They are quite few;

4. There are very few such topics.

14. Does it happen that in a conversation with your wife (husband) you feel constrained, you cannot find the right words?

1. Very rarely;

2. Quite rare;

3. Quite often;

4. Very often.

15. Do you and your wife (husband) have “family traditions”?

1. Yes;

2. Rather yes than no;

3. Rather no than yes;

4. No.

16. Can your wife (husband) understand without words what mood you are in?

1. Almost never;

2. Rarely enough;

3. Quite often;

4. Almost always;

17. Can you say that you and your wife (husband) have the same attitude towards life?

1. Yes;

2. Rather yes than no;

3. Rather no than yes;

4. No.

18. Does it happen that you do not tell your wife (husband) news that is important to you, but has no direct relation to her (to him)?

1. Very rarely;

2. Quite rare;

3. Quite often;

4. Very often.

19. Does your wife (husband) tell you about her physical condition?

1. Tells almost everything;

2. Tells a lot;

3. Tells quite a bit;

4. Tells almost nothing.

20. Do you feel if your wife (husband) likes what you do or say, if she (he) does not directly say so?

1. Almost always;

2. Quite often;

3. Quite rare;

4. Almost never;

21. Can you say that you agree with each other in the assessments of most of your friends?

1. No;

2. Rather no than yes;

3. Rather no than yes;

4. Yes.

22. Do you think your wife (husband) can predict whether you will like this or that movie, book, etc.?

1. I think so;

2. Rather yes than no;

3. Rather no than yes;

4. I think not.

23. If you happen to make a mistake, do you tell your wife (husband) about your failures?

1. I almost never tell;

2. I tell quite rarely;

3. I tell quite often;

4. I tell almost always.

24. Does it happen that when you are among other people, it is enough for your wife (husband) to look at you to understand how you feel about what is happening?

1. Almost always;

2. Quite often;

3. Quite rare;

4. Almost never;

25. How open do you think your wife (husband) is to you?

1. Fully frank;

2. Rather frank;

3. Rather vague;

4. Not frank at all.

26. Can you say that it is easy for you to communicate with your wife (husband)?

1. Yes;

2. Rather yes than no;

3. Rather no than yes;

4. No.

27. Do you often fool around talking to each other?

1. Very rarely;

2. Quite rare;

3. Quite often;

4. Very often.

28. Does it happen that after you told your wife (husband) about something important for you, you had to regret that you “blabbed too much”?

1. No, almost never;

2. Quite rare;

3. Quite often;

4. Yes, almost always.

29. What do you think, does your wife (husband) have troubles, bad mood, does she (he) get better from communicating with you?

1. No, almost never;

2. Quite rare;

3. Quite often;

4. Yes, almost always.

30. How frank are you with your wife (husband)?

1. Fully frank;

2. Rather frank;

3. Rather vague;

4. Completely indiscreet.

31. Do you always feel when your wife (husband) is offended or annoyed by something, if she does not want to show it to you?

1. Yes, it is;

2. Probably so;

3. This is hardly the case;

4. No, it's not.

32. Does it happen that your views on some important issue for you do not coincide with the opinion of your wife (husband)?

1. Very rarely;

2. Quite rare;

3. Quite often;

4. Very often.

33. Does it happen that your wife (husband) does not share with you news that is important for her (him) personally, but has no direct relation to you?

1. Very often;

2. Quite often;

3. Quite rare;

4. Very rare.

34. Can you understand without words what your wife's (husband's) mood is?

1. Almost always;

2. Quite often;

3. Quite rare;

4. Almost never.

35. Do you and your wife (husband) often have a “we feeling”?

1. Very often;

2. Quite often;

3. Quite rare;

4. Very rare.

36. How well do you understand your wife (husband)?

1. I don't understand at all;

2. Rather bad than good;

3. Rather good than bad;

4. I fully understand.

37. Does your wife (husband) tell you about her relationships with other people?

1. Tells practically nothing;

2. Tells quite a bit;

3. Tells a lot;

4. Tells almost everything.

38. Does it happen that in a conversation with you a wife (husband) feels tense, constrained, cannot find the right words?

1. Very rarely;

2. Quite rare;

3. Quite often;

4. Very often.

39. Do you have secrets from your wife (husband)?

1. Yes;

2. Rather eat than not;

3. Rather not than there;

4. No.

40. Do you often use funny nicknames when addressing each other?

1. Very often;

2. Quite often;

3. Quite rare;

4. Very rare.

41. Are there any topics that you find difficult and unpleasant to talk about with your wife (husband)?

1. There are a lot of such topics;

2. There are quite a few of them;

3. They are quite few;

4. There are very few such topics.

42. Do you and your wife (husband) often have disagreements about how to raise children?

1. Very rarely;

2. Quite rare;

3. Quite often;

4. Very often.

43. Do you think it is possible to say that it is easy for your wife (husband) to communicate with you?

1. Yes;

2. Rather yes than no;

3. Rather no than yes;

4. No.

44. Do you tell your wife (husband) about your physical condition?

1. I tell almost everything;

2. I tell a lot;

3. I tell quite a bit;

4. I don't tell almost anything.

45. Do you think your wife (husband) had to regret that she (he) told (l) you something very important for her (him)?

1. Almost never;

2. Quite rare;

3. Quite often;

4. Almost always.

46. Have you ever had the feeling that you and your wife (husband) have your own language, unknown to anyone around you?

1. Yes;

2. Rather yes than no;

3. Rather no than yes;

4. No.

47. Do you think your wife (husband) has secrets from you?

1. Yes;

2. Rather yes than no;

3. Rather no than yes;

4. No.

48. Does it happen that when you are among other people, it is enough for you to look at your wife (husband) in order to understand how she (he) relates to what is happening?

1. Very often;

2. Quite often;

3. Quite rare;

4. Very rare.

Processing and interpretation of test results

Key to the test

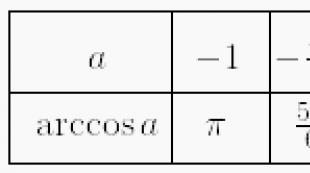

1. Confidence in communication

Self-rating: # +6; +18; -23; +30; -39; +44.

. rating given to the spouse: No. +10; +19; +25; -33; -37; -47.

2. Mutual understanding between spouses

Self-rating: # +4; +20; -24; +31; +34; -36.

. rating given to the spouse: No. +5; +8; +9; -16; +22; +48.

3. Similarity in the views of the spouses: № +1; -7; +17; -21; +32; +42.

4. Common symbols of the family: № +3; -11; +15; +35; +40; +46;

5. Ease of communication between spouses: № -2; +14; +26; -27; +38; +43.

6. Psychotherapeutic communication: № +12; -13; +28; -29; -41; +45.

Handling test results

Points for each answer are awarded according to the following table:

Sign before question number a b c d

+ 4 3 2 1

- 1 2 3 4

The final indicator on the scale is equal to the sum of the points scored by the respondent on this scale, divided by the number of questions in this scale.