Years of Constantine's reign 1. Is Emperor Constantine a Christian or a secret pagan? Executions of Crispus and Fausta

Having defeated all his rivals, he became the sole ruler and, for political reasons, moved the capital of the empire to Byzantium, later called Constantinople.

1. Parents

Secretly, during the absence of Galerius, Constantine escaped from captivity and went to his father in the city of York, in Great Britain, who, before his death, managed to transfer power over the west to him. The gallery had to come to terms with this, but under the pretext that Constantine was still very young, he recognized him only as a Caesar. August he appointed Severus. Formally, Constantine held the position of a subordinate in relation to Flavius Severus, but in reality this was not the case. In Gaul, where the residence of Constantine was located, there were legions personally devoted to him, the population of the province supported him, thanks to the mild and fair policy of his father. Flavius Severus did not have such a solid foundation.

2.1. Revolt of Maxentius

3.2. Politics in the sphere of religion

At the beginning of his reign, Constantine, like all emperors, was a pagan. In the year after visiting the sacred grove of Apollo, he allegedly even had a vision of the sun god. However, already 2 years later, during the war with Maxentius, according to Constantine, Christ appeared to him in a dream, who ordered the letters to be drawn on the shields and banners of his army RH, the next day Constantine saw in the sky to find the cross. After defeating Licinius in the year, Constantine pressed for his acceptance of religious freedom by issuing the Edict of Milan. Constantine himself was baptized only before his death, which did not prevent him from intervening in subtle religious disputes, for example, at the First Council of Nicaea, he strongly supported catholists against the Arians. Churches were built throughout the empire. Sometimes old pagan temples were dismantled for their construction.

3.3. Monetary reform

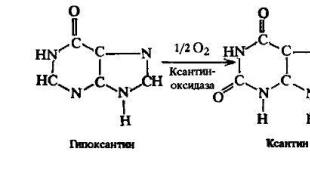

After rampant inflation in the third century, associated with the production of paper money to pay for government spending, Diocletian tried to restore the reliable minting of silver and gold coins. Constantine abandoned this conservative monetary policy, preferring instead to concentrate on the minting of a large number of good standard gold coins - solidus, gold-silver alloy - to ensure that fiduciary coinage could be maintained along with the gold standard. An anonymous author may contemporary in Treatise on Warfare Where Rebus Bellikis held that as a result of this monetary policy, the rift between classes widened: the wealthy benefited greatly from stable purchasing power on gold coin, while the poor were constantly humiliated. Later emperors such as Julian the Apostate tried to mint copper coins.

Constantine's monetary policy was closely linked to his religious beliefs, in that the increase in coinage was due to measures to confiscate - taken after and in - all gold, silver and bronze statues from pagan temples that were declared imperial property. and like cash. Two imperial commissaries for each province were given the task of collecting these statues and melting them down for immediate minting - with the exception of the total number of bronze statues, which were used as public monuments to equip the new capital in Constantinople.

3.4. The construction of Constantinople

Constantine was no exception to this rule. The first time he visited Rome after the victory over Maxentius, subsequently visiting there only twice. Constantine burned with the dream of creating a new capital, which would symbolize the beginning of a new era in the history of Rome. The basis for the future city was the ancient Greek city of Byzantium, located on the European coast of the Bosporus. The old city was expanded and surrounded by impregnable fortress walls. It had a hippodrome and many temples, both Christian and pagan. Works of art were brought to Byzantium from all over the empire: paintings, sculptures. Construction began in the year and after 6 years on May 11, Constantine officially transferred the capital of the Roman Empire to Byzantium and named it New Rome(gr. Νέα Ῥώμη , lat. Nova Roma), However, this name was soon forgotten, and already during the life of the emperor, the city began to be called Constantinople- that is, the city of Constantine.

3.5. Executions of Crispus and Fausta

Shortly before his death, Constantine led a successful war against the Goths and Sarmatians. At the beginning of the year, the sick emperor went to Helenopolis to use the baths. Feeling worse, he ordered to be transported to Nicomedia, and here, on Constantine's deathbed, the Arian bishop Eusebius of Nicomedia was baptized in Christianity. Before his death, having gathered the bishops, he admitted that he dreamed of being baptized in the waters of the Jordan, but by the will of God he accepts him here (Eusebius: "Life of Constantine", 4, 62).

Constantine had previously divided the Roman Empire among his three sons: Constantine II (ruled 337-340) received Great Britain, Spain and Gaul; Constantius II (ruled 337-361) received Egypt and Asia; Constans (reigned 337–350) received Africa, Italy and Pannonia, and after his brother Constantine II's death

Constantine I, known as the Great (288? - 337), is a Roman emperor. Born on February 27, presumably 288 AD. in Naissa (now Nish) in Upper Moesia (Serbia). He was the illegitimate son of Constantius and Flavia Helena (according to the description of St. Ambrose, the owner of a roadside inn). As a boy, Constantine was sent - practically as a hostage - to the court of the rulers of the eastern part of the Roman Empire. In 302 he accompanied the emperor Diocletian

Rise to power.

Constantine's patience was soon rewarded. Galerius died in 311. And Maximinus Daia (who in 310 assumed the title of August of the East) immediately led an army to the shores of the Bosporus and at the same time entered into negotiations with Maxentius. This threw Licinius into the hands of Constantine, who entered into an alliance with him and gave him his half-sister Constance as a bride. In the spring of 312, Constantine crossed the Alps—before Maxentius had finished his preparations—with an army that, according to his panegyrist (perhaps an underestimation of his numbers), numbered 25,000, and according to Zonoras, about 100,000 men. He stormed Susa, defeated the generals Maxentius at Turin and Verona, and headed back to Rome. This bold move, quite out of step with Constantine's usual caution, seems to have been the result of a single event: as Eusebius' Life of Constantine says, Constantine's eyes had a miraculous vision of a Flaming Cross appearing in the sky at noon with an inscription below it in Greek: "Evtouta vika" ("By this you will overcome"), and it led to his conversion to Christianity.

Eusebius claims to have heard this story from the mouth of Constantine; but he wrote after the death of the emperor, and she was obviously unfamiliar to him in this form when he wrote the History of the Church. The author of another work, On the Death of the Persecutors ("De mortibus persecutorum"), was a well-informed contemporary of Constantine (this work is attributed to Lactantius, a writer and orator who lived under Diocletian and died in 317), and he tells us that the sign of the Burning Cross appeared Constantine in a dream; and even Eusebius adds that it was not a vision of the day, but a dream of the night. Be that as it may, Konstantin began to wear a monogram of his own invention ( see the picture on the right).Maxentius, believing in numerical superiority, set out from Rome, ready to challenge the crossing in the north of the Tiber across the Miliev Bridge (Pons Vulvius - now Ponte Molle). The army, perfectly trained by Constantine for six years, immediately proved its superiority. The Gallic cavalry drove the left flank of the enemy into the Tiber, and Maxentius died with him, as they said, due to the collapse of the bridge (October 28, 312). The remnants of his army surrendered of their own accord, and Constantine incorporated them into the ranks of his army, with the exception of the Praetorian Guard, which was eventually disbanded.

Thus, Constantine became the undisputed ruler of Rome and the West, and Christianity, though not yet accepted as the official religion, was secured by the Edict of Mediolanum (now Milan) tolerant attitude throughout the empire. This edict was the result of a meeting between Constantine and Licinius in 313 at Mediolanum, where the latter married Constance, Constantine's sister. In 314, a war broke out between the two Augusts, the cause of which, as historians tell us, was the betrayal of Bassian, the husband of Constantine's sister Anastasia, whom he wanted to raise to the rank of Caesar. After two hard-won victories, Constantine went to the world, annexing Illyricum and Greece to his dominions. In 315 Constantine and Licinius were consuls. Peace lasted for about nine years, during which Constantine, acting wisely as a ruler, strengthened his position, while Licinius (who resumed the persecution of Christians in 312) constantly lost his position. Both emperors raised powerful armies, and in the spring of 323 Licinius, whose troops are said to have been outnumbered, declared war. He was defeated twice - first at Andrianopolis (July 1), then at Chrysopolis (September 18), when he tried to lift the siege of Byzantium and, finally, was captured in Nicomedia. The intercession of Constance saved his life, and he was interned at Thessalonica, where he was executed the following year on charges of criminal correspondence with barbarians.

Constantine is the emperor of East and West.

Constantine now reigned as sole emperor in East and West, and in 325 presided over the Council of Nicaea. The following year, his eldest son Crispus was banished to Pola, and there he was put to death on charges brought against him by Fausta. Shortly thereafter, Constantine seemed to be convinced of his innocence and ordered the execution of Fausta. The true nature of the circumstances of this case remains a mystery.

In 326, Constantine decided to move the seat of government from Rome to the East, and by the end of the year the foundation stone of Constantinople had been laid. Constantine considered at least two more locations for a new capital, Serdika (now Sofia) and Troy, before choosing Byzantium. This move was probably related to his decision to make Christianity the official religion of the empire. Rome, naturally, was the stronghold of paganism, which the senate majority clung to with ardent devotion.

In 332, Constantine was asked to help the Sarmatians in the fight against the Goths, over whom his son won a major victory. Two years later, when 300,000 Sarmatians settled on the territory of the empire, war broke out again on the Danube. In 335, an uprising in Cyprus gave Constantine a pretext for executing the young Licinius. In the same year, he divided the empire between his three sons and two nephews, Dalmatius and Annibalian. The latter received the vassal kingdom of Pontus and, in spite of the Persian rulers, the title of king of kings, while others ruled as Caesars in their provinces. At the same time, Constantine remained the supreme ruler. Finally, in 337, Shapur II, the Persian king, laid claim to the provinces conquered by Diocletian, and war broke out. Constantine was ready to personally lead his army, but fell ill and, after unsuccessful treatment with baths, died in Ankiron, a suburb of Nicomedia, on May 22, shortly before his death, having received Christian baptism from the hands of Eusebius. He was buried in the Church of the Apostles in Constantinople.

Constantine and Christianity.

Constantine received the right to be called "Great" rather by virtue of his deeds than by what he was; and it is true that his intellectual and moral qualities were not so high as to secure this title for him. His claim to greatness rests chiefly on the fact that he foresaw the future that awaited Christianity and determined to profit from it for his empire, and on the accomplishments that completed the work begun by Aurelian and Diocletian, by which a quasi-constitutional monarchy, or "principate" August, was transformed into naked absolutism, sometimes called "dominate". There is no reason to doubt the sincerity of Constantine's conversion to Christianity, although we cannot attribute to him the passionate piety that Eusebius bestows on him, nor can we accept as true the stories that go around his name. The moral precepts of the new religion could not but influence his life. And he gave his sons a Christian education. However, for reasons of political expediency, Constantine delayed the full recognition of Christianity as the state religion until he became the sole ruler of the empire. Although he not only ensured a tolerant attitude towards him immediately after the victory over Maxentius, but already in 313 he came to his defense against the opposition movement of the Donatists and the next year presided over the council in Arelate. In a number of acts, he freed the Catholic Church and the clergy from taxes and granted them various privileges that did not apply to heretics, and gradually the attitude of the emperor towards paganism was revealed: it could be called contemptuous tolerance. From the heights of a state-recognised religion, it has slid down to mere superstition. At the same time, pagan rites were allowed, except in places where they were considered undermining moral principles. And even in the last years of the reign of Constantine, we find laws in favor of the local priests - the flamens and their colleges. In 333 or later, the cult of the Flavian family, as the imperial family was called, was established; however, sacrifices in the new temple were strictly forbidden. Only after the final victory of Constantine over Licinius did the pagan symbols disappear from the coins, and a distinct Christian monogram appeared on them (which already served as the mark of the mint). From that time on, the heresy of Arianism demanded the constant attention of the emperor, and by the fact that he presided over the council at Nicaea, and subsequently, having sentenced Athanasius to exile, he not only spoke more frankly than before about his involvement in Christianity, but also showed determination to assert his supremacy in affairs of the Church. Not at all doubting that his rank of Pontiff Great gives him supreme authority over the religious affairs of the entire empire and putting Christianity in order is within his competence. In this matter, his insight betrayed him. It was comparatively easy to apply coercion to the Donatists, whose resistance to temporal power was not wholly spiritual, but was largely the result of not-so-pure motives. But the heresy of Arianism raised fundamental questions which, according to Constantine, could be reconciled, but in fact, as Athanasius rightly believed, they exposed essential contradictions of the doctrine. The result foreshadowed the emergence of a process that led to the fact that the Church, which Constantine hoped to make an instrument of absolutism, became a determined opponent of the latter. Not worthy of more than a cursory mention is the legend according to which Constantine, stricken with leprosy after the execution of Crispus and Fausta, received absolution and was baptized by Sylvester I and, with his donation to the bishop of Rome, laid the foundation for the secular power of the papacy.

Political system of Constantine.

Constantine's political system was the end result of a process which, although it lasted as long as the empire existed, took distinct shape under Aurelian. It was Aurelian who surrounded the person of the emperor with oriental splendor, wore a diadem and a robe adorned with precious stones, took the rank of dominus (lord) and even deus (god); turned Italy into a kind of province and gave the official way to the economic process, which replaced the treaty regime with the regime of status. Diocletian tried to protect the new form of despotism from usurpation by the army by creating a cunning system of joint rule of the empire with two lines of succession of power, bearing the names of Jupiter and Hercules, but this succession was carried out not by inheritance, but by adoption. This artificial system was destroyed by Constantine, who established dynastic absolutism in favor of his family - the Flavian clan, evidence of whose cult was found both in Italy and in Africa. In order to surround himself with the royal court, he created an official aristocracy to replace the senatorial order, which the "soldier emperors" of the 3rd century AD. practically devoid of any significance. This aristocracy he showered with titles and special privileges, so, for example, he created a modified patricianism, freed from the tax burden. Since the senate now meant nothing, Constantine was able to allow its members to be admitted to the career of provincial administrators, which since the reign of Gallienus had been almost closed to them, and to grant them some empty privileges, such as free election of quaestors and praetors, and on the other hand, the right to be judged by his equals was taken away from the senator, and he passed under the jurisdiction of the provincial governor.

Administrative structure of the Roman Empire under Constantine.

In the matter of the administrative structure of the empire, Constantine completed what Diocletian had begun by separating civil and military functions. Under him, the praetorian prefects completely ceased to perform military duties and became heads of the civil administration, especially in matters of legislation: in 331 their decisions became final, and no appeal to the emperor was allowed. The civil governors of the provinces had no authority over the military forces commanded by the dukes; and in order to secure the most reliable protection against usurpation, which served as a division of power, Constantine hired comites, who constituted a significant part of the official aristocracy, to observe and report on how the military was doing, as well as an army of so-called agents who, under the guise of inspecting the imperial The postal service carried out a massive espionage system. As regards the organization of the army, Constantine subordinated command to military magistrates in charge of infantry and cavalry. He also opened access for the barbarians, especially the Germans, to positions of high responsibility.

Legislation of Constantine.

The organization of society according to the principle of strict heredity in corporations or professions, in part, no doubt, had already ended before Constantine came to power. But his legislation continued to forge the fetters that tied each person to the caste from which he came from. Such originales (hereditary estates) are mentioned in the very first laws of Constantine, and in 332 the hereditary status of the agricultural estate of the colones is recognized and affirmed in life.

|

In general legislation, Constantine's reign was a time of feverish activity. About three hundred of his laws have come down to us in codes, especially in the code of Theodosius. In these codes, a sincere desire for reform and the influence of Christianity can be seen, for example, in demanding humane treatment of prisoners and slaves and punishment for crimes against morality. However, they are often crude in thought and pompous in style, and were clearly written by official rhetoricians rather than experienced lawyers. Like Diocletian, Constantine believed that the time had come when society needed to be restructured by decrees of despotic power, and it is important to note that since then we have met with the undisguised assertion of the will of the emperor as the only source of law. In fact, Constantine embodies the spirit of absolute power, which was to dominate for many centuries both in the Church and in the state.

The history of Istanbul is about 2,500 years old. In 330, the capital of the Roman Empire was transferred to Byzantium (this was the original name of the city of Istanbul) by Emperor Constantine the Great. Constantine, who converted to Christianity, contributed to the strengthening of the Christian Church, which actually occupied a dominant position under him, and to the formation of the Byzantine Empire, as the successor of the Roman. For his deeds, he was canonized as a Saint Equal-to-the-Apostles in the Orthodox Church.

Emperor Constantine the Great receives the sign of the Cross of God

Constantine the Great biography

The biography of Constantine the Great is quite well studied, thanks to the numerous surviving testimonies. The future emperor was born approximately in 272 on the territory of modern Serbia. His father was Constantius I Chlorus (who later became Caesar), and his mother was Elena (the daughter of a simple innkeeper). She played a very important role both in the life of her son and in the development of Christianity as the state religion of the Byzantine Empire. Elena, the mother of Constantine the Great, was canonized by the Orthodox Church as a Saint Equal-to-the-Apostles for her pilgrimage to the Holy Land, during which many churches were founded and parts of the Cross of the Lord and other Christian shrines were found.

Constantius, the father of Constantine, was forced to divorce Helen and marry the stepdaughter of Emperor Augustus Maximilian Herculius Theodora, from this marriage Constantine had half-sisters and brothers.

Life of Constantine the Great (Byzantine)

As a result of the political struggle, the father of Constantine the Great, Constantius came to power in the status of Caesar, and then the full emperor of the western part of the Roman Empire, on a par with Emperor Galerius, who then ruled the eastern part. Constantius was already weak and old. Anticipating his imminent death, he invited his son Konstantin to his place. After the death of Constantius, the army of the western part of the empire proclaimed Constantine their emperor, which, in turn, did not please Galerius, who did not officially recognize this fact.

Constantine the Great - the first Christian emperor

At the beginning of the 4th century, the Roman Empire was a politically fragmented state. In fact, up to 5 rulers were in power, calling themselves both Augusts (senior emperors) and Caesars (junior emperors).

In 312, Constantine defeated the troops of Emperor Maxentius in Rome, in honor of which the triumphal arch of Constantine was erected there. In 313, Constantine's main competitor, Emperor Licinius, defeated all his opponents and consolidated most of the Roman Empire in his hands. Constantine was now subject to Gaul, Italy, African possessions and Spain, and Licinius - all of Asia, Egypt and the Balkans. Over the next 11 years, Constantine gained power throughout the empire by defeating Licinius and on September 18, 324, he was declared the sole emperor.

After Constantine the Great became emperor, he first of all changed the administrative structure of the empire and, as they would say today, strengthened the vertical of power, since a country that had experienced 20 years of civil wars needed stability.

Coins of Constantine the Great can be found in fairly good condition and are now at international auctions.

Golden solidus of Emperor Constantine, 314

Constantine the Great and Christianity

During his reign, Emperor Constantine the Great, in fact, made Christianity the state religion. He actively led the reunification of various parts of the church, resolving all internal contradictions, in particular, in 325, he gathered the famous Council of Nicaea, which condemned the Arians and eliminated the emerging schism within the church.

Throughout the empire, Christian churches were actively built, for their construction, pagan temples were often destroyed. The church was gradually freed from all taxes and duties. In fact, Constantine gave Christianity a special status, which marked the rapid development of this religion, and made Byzantium the future center of the Orthodox world.

Founding of Constantinople by Emperor Constantine the Great

The empire under the newly proclaimed emperor Constantine needed a new capital, both because of external threats and because of the elimination of the problem of internal political struggle. In 324, Constantine's choice fell on the city of Byzantium, which had an excellent strategic position on the banks of the Bosporus. This year, the active construction of the new capital begins, various cultural values from all over the empire are delivered to it by order of the emperor. Palaces, temples, hippodrome, defensive walls are being erected. It was under Constantine that the famous was founded. On May 6, 330, the emperor officially transferred the capital to Byzantium, and named it New Rome, which almost immediately began to be called Constantinople in his honor, since the population of the city did not accept the official name.

Constantine the Great presents the city of Constantinople as a gift to the Mother of God. Fresco of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul

Death and canonization of the Holy Equal-to-the-Apostles Tsar Constantine

Emperor Constantine the Great died on May 22, 337 in what is now Turkey. Before his death, he was baptized. It so happened that the great helper and companion of the Church of Christ, who made Christianity the state religion of the largest country in the world at that time, was himself baptized in the last days of his life. This did not prevent him, for all his deeds aimed at strengthening the power of the Christian Church, from being canonized as a saint in the rank of Equal-to-the-Apostles — equal to the Apostles of Christ themselves (Saint Equal-to-the-Apostles Tsar Constantine). The reckoning of Constantine to the saints took place after the division of the churches into Orthodox and Catholic, which is why the Roman Catholic Church did not include him in the list of its saints.

It is absolutely clear that both Emperor Constantine the Great himself and his mother Helen made a huge contribution to the formation of the Byzantine civilization, the cultural heirs of which are a number of modern states.

Exaltation of the Holy Cross. Emperor Constantine and his mother Helena

Film Constantine the Great

In 1961, the film Constantino the Great (Italian Costantino il grande) was filmed in Italy. The picture tells about the youth of Emperor Constantine. The film takes place before the famous Battle of the Milvian Bridge. Filming took place in Italy and Yugoslavia. Directed by Lionello De Felice, starring Cornel Wilde as Constantine, Belinda Lee as Fausta, Massimo Serato as Maxentius. Duration - 120 minutes.

ANCIENT WORLD HISTORY:

East, Greece, Rome/

I.A. Ladynin and others.

Moscow: Eksmo, 2004

Section V

Late Empire era (dominate)

Chapter XX.

Formation of the dominant system (284-337)

20.2. Reign of Constantine the Great (306-337)

Soon after the abdication of Diocletian, a struggle for power broke out between his heirs (306-324). In July 306, 56-year-old Constantius I Chlorus died in Eborac, and his legions proclaimed Caesar the son of Constantius, 20-year-old Gaius Flavius Valerius Constantine (306-337). Instead of Constantius, Galerius appointed Severus Augustus and reluctantly recognized Constantine as Caesar. At the end of October 306, Maxentius, the son of Maximian Herculius, seized power in Rome: first he declared himself Caesar, and the next year - in August. Soon the 66-year-old Maximian himself returned to power. He entered into an alliance with Constantine, married his daughter to him and recognized him as Augustus. So in 307, the empire turned out to have 5 August at once.

Having suffered a defeat in the fight against Maxentius and Maximian, in April 307 Severus perished. In November 308, Galerius declared Valery Licinius August, and in 309 Maximinus Daza. Soon, as irrepressible in his lust for power as the treacherous Maximian, who quarreled with his son and betrayed his son-in-law, suffered a complete defeat and died (310). In May 311 Galerius, the most active enemy of the Christians, died in Nicomedia. Before his death, he issued an edict on religious tolerance, in which he repented for the 8-year persecution of Christians. Galerius' successor in the East was Licinius. In 312, Constantine, at the head of his Gallic army, invaded Italy and utterly defeated the troops of Maxentius in the battle of Verona. At the end of October of the same year, in the battle of the Milvian Bridge, Maxentius was finally defeated and died. Constantine entered Rome and, having executed the two sons of Maxentius, declared a general amnesty, which won the favor of the Romans.

In the summer of 313, Maximinus Daza died in the fight against Licinius. All the eastern provinces were under the rule of Licinius. In the same year, Constantine and Licinius published the so-called. Mediolan (or Milan) edict, which recognized the equality of Christianity with all other religions. Property confiscated from Christian communities was subject to return or compensation. Constantine and Licinius divided the empire: the first got the West, the second the East. In 314, a conflict broke out between them, followed by a redistribution of possessions: the defeated Licinius gave Constantine the Balkan Peninsula (with the exception of Thrace). Peace lasted about 10 years. In 324, a war broke out between Constantine and Licinius over disputed Thrace. In September of the same year, Licinius was completely defeated, capitulated, and a few months later was killed on the orders of Constantine. The latter became the sole ruler of the empire (324-337).

The political course of Constantine became a direct continuation of the policy of Diocletian. In 314, he carried out a new monetary reform. A new gold coin was introduced into circulation in the West of the empire (since 324 and in the East) - solidus (minted at the rate of 72 coins per pound). In addition to the solidus, changeable silver denarii were in circulation in the provinces. The innovation made it possible to stabilize the financial system and somewhat revive the market.

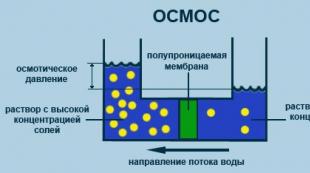

Under Constantine, the process of attachment to the place of residence and work of curials, artisans and columns, which had begun under Diocletian, continued. The obligations of the curials, financially responsible for tax revenues from the townspeople, were lifelong and hereditary. The ranks of the bankrupt curials were forcibly replenished by wealthy people. Membership in craft colleges also became hereditary. In particular, associations of artisans who served the imperial workshops were subjected to enslavement. In relation to the performance of duties, members of corporations were bound by mutual responsibility. The attachment of columns to the land received its legal formalization in the constitution of Constantine "On the runaway columns" (332), where for the first time the forced return of runaway columns to their place of residence was recorded. The number of columns increased due to the captured barbarians. Unbearable tax oppression and abuses of imperial officials brought to life such a legal institution as the patrocinium. Peasants, artisans and curials voluntarily passed under the patronage of local magnates and became their colonies. They received their former landed property already on the rights of precarious (conditional) possession. In return, the magnates provided their colonies with protection from the oppression of the authorities.

Constantine continued the military reform of Diocletian. He disbanded the praetorian cohorts (312), and from the composition of the mobile troops he singled out privileged palace units stationed in Rome and the residences of the emperor. The army was replenished with detachments of barbarians, who received Roman citizenship for their service, and with it the opportunity to make a career in the military-bureaucratic structures of the Late Empire. Gradually, the military profession also became hereditary. The time of Constantine (if you do not take into account the bloody struggle for power) was relatively calm: only minor border wars were fought under him (in particular, on the Danube).

Under Constantine, the territory of the empire was divided into 4 large administrative districts - prefectures, headed by the praetorian prefects. The military command was in the hands of 4 military masters. Praetorian prefects and military masters were appointed by the emperor. The former administrative division into provinces and dioceses has been preserved. The cumbersome military-bureaucratic system was based on the principle of a strict hierarchy and the subordination of lower managers to those of higher rank. All ranks of the upper echelon of the administrative apparatus were divided into 6 categories: “the most noble”, “radiant”, “most venerable”, “brightest”, “most perfect” and “outstanding” (the lowest rank). Their owners were considered as personal servants of the emperor (comites, domestici). Palace positions associated with the service of the “sacred person” of the emperor were considered the highest in the empire (head of the “sacred bed”, groom, keeper of the “sacred garment”, head of the main office, etc.).

In the field of religious policy, Constantine pursued a fundamentally different course than Diocletian. He saw in Christian doctrine and ecclesiastical organization a potential pillar of the emperor's absolute power. Being a sober-minded and pragmatic politician, he was well aware of the futility of the policy of persecution. Constantine himself, like his father, initially had a reputation among Christians as a ruler who was completely loyal to Christianity. Therefore, the publication of the Edict of Mediolanum in 313 was a completely logical and politically justified step (as for his colleague Licinius, his attitude towards Christians was not consistent: in 320 he again subjected them to persecution). Even earlier, Constantine freed the Christian clergy from all personal duties in favor of the state. The edict of 315 guaranteed free prayer meetings for Christians. Christians were given back their civil rights taken from them under Diocletian and Galerius. Constantine himself remained a pagan (he was baptized only on the eve of his death). Nevertheless, he closed some pagan temples, abolished a number of priestly offices and confiscated part of the temple valuables.

Meanwhile, the church itself was shaken by confessional disputes. There were such mass heresies as Donatism and Arianism (the latter soon spread widely throughout the empire). It was in the interests of the emperor to prevent a church schism, so he invariably took the side of the orthodox episcopate and severely persecuted heretics. To put an end to disagreements, Constantine summoned all the bishops of East and West to the First Ecumenical Council, held in 325 in the Asia Minor city of Nicaea. At the council, under pressure from the emperor, most of the bishops (about 300 people) condemned Arianism. Then the first Creed was adopted. True, a few years later Constantine began to lean towards Arianism and in 337, while on his deathbed, was baptized by the Arian Bishop Bsebius of Nicomedia. Nevertheless, Constantine's services to the church were so significant that after the death of the emperor, the clergy honored him with the name "Great" and canonization (although this treacherous and cruel despot killed his eldest son and nephew, executed his wife and committed many other crimes).

In 330, Constantine solemnly transferred the capital of the empire to Constantinople (New Rome), which stood on the European coast of the Thracian Bosporus on the site of the ancient Greek city of Byzantium. Enormous funds were spent on the construction and decoration of Constantinople. Palaces, a stadium, a hippodrome, baths and libraries were built in the city, surrounded by powerful fortifications (the so-called "Constantine Wall"). A huge number of statues were taken from Rome to the new capital. The transfer of the capital to the East had a symbolic meaning: there was a complete and final break with the traditions of the "republican monarchy". From now on, the emperor was no longer "first among equals." He was an absolute monarch, before whom his subjects obsequiously prostrated themselves, as before some oriental despot. Diocletian and Constantine wore a diadem and luxurious, jeweled robes. At court, a strict ceremony was introduced with bows and kissing of the hands and feet of the ruler.

Constantine the Great. Bronze. 4th century Rome.

About 285 AD e. in Naissus, Caesar Flavius Valerius Constantius I Chlorus, the Roman governor in Gaul, and his wife Helen Flavius had a son, Flavius \u200b\u200bValerius Constantine. Constantius Chlorus himself was a modest, gentle and courteous man. Religiously, he was a monotheist, worshiped the sun god Sol, who during the time of the Empire was identified with eastern deities, especially with the Persian god of light Mitra - the god of the sun, the god of contract and consent. It was to this deity that he dedicated his family. Elena, according to some sources, was a Christian (there were many Christians around Constantius, and he treated them very kindly), according to others, she was a pagan. In 293, Constantius and Helen were forced to divorce for political reasons, but the ex-wife still occupied a place of honor at his court. The son of Constantius had to be sent from a young age to the court of Emperor Diocletian in Nicomedia.

By that time, the Christian Church already played a very important role in the life of the Empire, and millions of people were Christians - from slaves to the highest officials of the state. There were many Christians at the court in Nicomedia. However, in 303, Diocletian, under the influence of his son-in-law Galerius, a rude and superstitious pagan, decided to destroy the Christian Church. The most terrible persecution of the new religion of an all-imperial character began. Thousands and thousands of people were brutally tortured for belonging to the Church alone. It was at this moment that young Constantine found himself in Nicomedia and witnessed a bloody bacchanalia of murders that caused grief and regret in him. Brought up in an atmosphere of religious tolerance, Constantine did not understand the politics of Diocletian. Constantine himself continued to honor Mitra-Sun, and all his thoughts were aimed at strengthening his position in that difficult situation and finding a way to power.

In 305, Emperor Diocletian and his co-ruler Maximian Heruclius relinquished power in favor of successors. In the east of the Empire, power passed to Galerius, and in the west - to Constantius Chlorus and Maxentius. Constantius Chlorus was already seriously ill and asked Galerius to release his son Constantine from Nicomedia, but Galerius delayed the decision, fearing a rival. Only a year later, Konstantin finally managed to get Galerius' consent to leave. The terminally ill father blessed his son and gave him command of the troops in Gaul.

In 311, suffering from an unknown illness, Galerius decided to stop the persecution of Christians. Apparently, he suspected that his illness was "the revenge of the God of Christians." Therefore, he allowed the Christians to "assemble freely for their meetings" and "offer prayers for the safety of the emperor." A few weeks later Galerius died; under his successors, the persecution of Christians resumed, albeit on a smaller scale.

Maxentius and Licinius were two Augusts, and Constantine was proclaimed by the senate as Chief Augustus. The next year, war broke out in the west of the Empire between Constantine and Maxentius, as Maxentius claimed to be the sole ruler. Licinius joined Constantine. Of the 100,000-strong army stationed in Gaul and at the disposal of Constantine, he was able to allocate only a fourth, while Maxentius had 170,000 infantry and 18,000 cavalry. Constantine's campaign against Rome began, therefore, in unfavorable conditions for him. Sacrifices were made to the pagan gods in order for the gods to reveal the future, and their predictions were bad. In the autumn of 312 Constantine's small army approached Rome. Constantine, as it were, challenged the eternal city - everything was against him. It was at this time that visions began to appear to the religious Caesar, which strengthened his spirit. First, he saw in a dream in the eastern part of the sky a huge fiery cross. And soon angels appeared to him, saying: "Konstantin, with this you will win." Inspired by this, Caesar ordered that the sign of the name of Christ be inscribed on the shields of the soldiers. Subsequent events confirmed the emperor's visions.

The ruler of Rome, Maxentius, did not leave the city, having received the oracle's prediction that he would die if he left the gates of Rome. The troops were successfully commanded by his commanders, relying on a huge numerical superiority. The fateful day for Maxentius was the anniversary of his gaining power - October 28th. The battle broke out under the walls of the city, and the soldiers of Maxentius had a clear advantage and a better strategic position, but the events seem to confirm the proverb: "Whom God wants to punish, he deprives him of reason." Suddenly, Maxentius decided to seek advice from the Sibylline Books (a collection of sayings and predictions that served for official divination in ancient Rome) and read in them that the enemy of the Romans would die that day. Encouraged by this prediction, Maxentius left the city and appeared on the battlefield. When crossing the Mulvinsky bridge near Rome, the bridge collapsed behind the emperor; Maxentius' troops were seized with panic, they rushed to run. Crushed by the crowd, the emperor fell into the Tiber and drowned. Even the pagans saw Constantine's unexpected victory as a miracle. He himself, of course, had no doubt that he owed his victory to Christ.

It was from that moment that Constantine began to consider himself a Christian, but he has not yet accepted baptism. The emperor understood that the strengthening of his power would inevitably be associated with actions contrary to Christian morality, and therefore was in no hurry. The rapid adoption of the Christian faith might not please the supporters of the pagan religion, who were especially numerous in the army. Thus, a strange situation arose when a Christian was at the head of the empire, who was not formally a member of the Church, because he came to faith not through the search for truth, but as an emperor (Caesar), seeking God, protecting and sanctifying his power. This ambiguous position subsequently became the source of many problems and contradictions, but so far, at the beginning of his reign, Constantine, like the Christians, was enthusiastic. This is reflected in the Edict of Milan on religious tolerance, drawn up in 313 by the emperor of the West Constantine and the emperor of the East (Galerius' successor) Licinius. This law differed significantly from the decree of Galerius of 311, which was also poorly implemented.

The Edict of Milan proclaimed religious tolerance: "Freedom in religion should not be constrained, on the contrary, it is necessary to give the right to take care of Divine objects to the mind and heart of everyone, according to his own will." It was a very bold move that made a huge difference. The religious freedom proclaimed by Emperor Constantine remained a dream of mankind for a long time. The emperor himself subsequently changed this principle more than once. The edict gave Christians the right to spread their teachings and convert others to their faith. Until now, this was forbidden to them as a "Jewish sect" (conversion to Judaism was punishable by death under Roman law). Constantine ordered the return to the Christians of all property confiscated during the persecution.

Although during the reign of Constantine the equality of paganism and Christianity proclaimed by him was respected (the emperor allowed the ancestral cult of the Flavians and even the construction of a temple "to his deity"), all the sympathies of the authorities were on the side of the new religion, and Rome was decorated with a statue of Constantine with his right hand raised for the sign of the cross.

The emperor was careful to ensure that the Christian Church had all the privileges that pagan priests used (for example, exemption from official duties). Moreover, soon the bishops were given the right of jurisdiction (trial, legal proceedings) in civil cases, the right to release slaves to freedom; thus the Christians received, as it were, their own judgment. 10 years after the adoption of the Edict of Milan, Christians were allowed not to participate in pagan festivities. Thus, the new significance of the Church in the life of the Empire received legal recognition in almost all areas of life.

The political life of the Roman Empire meanwhile went on as usual. In 313, Licinius and Constantine remained the sole rulers of Rome. Already in 314, Constantine and Licinius began to fight among themselves; the Christian emperor won two battles and achieved the annexation of almost the entire Balkan Peninsula to his possessions, and after another 10 years a decisive battle took place between the two rival rulers. Constantine had 120 thousand infantry and cavalry and 200 small ships, while Licinius had 150 thousand infantry, 15 thousand cavalry and 350 large three-oared galleys. Nevertheless, the army of Licinius was defeated in a land battle near Adrianople, and the son of Constantine Crispus defeated the fleet of Licinius in the Hellespont (Dardanelles). After another defeat, Licinius surrendered. The winner promised him life in exchange for renunciation of power. However, the drama didn't end there. Licinius was exiled to Thessaloniki and executed a year later. In 326, on the orders of Constantine, his ten-year-old son, Licinius the Younger, was also killed, despite the fact that his mother, Constantia, was Constantine's half-sister.

At the same time, the emperor ordered the death of his own son Crispus. The reasons for this are unknown. Some contemporaries believed that the son was involved in some kind of conspiracy against his father, others that he was slandered by the second wife of the emperor, Fausta (Crispus was the son of Constantine from his first marriage), trying to clear the way to power for their children. A few years later, she also died, suspected by the emperor of adultery.

Despite the bloody events in the palace, the Romans loved Constantine - he was strong, handsome, polite, sociable, loved humor and was in perfect control of himself. As a child, Konstantin did not receive a good education, but he respected educated people.

Constantine's domestic policy was to gradually promote the transformation of slaves into dependent peasants - colones (simultaneously with the growth of dependence and free peasants), to strengthen the state apparatus and increase taxes, to widely grant the senatorial title to wealthy provincials - all this strengthened his power. The emperor dismissed the Praetorian Guard, rightly considering it a source of domestic conspiracies. Barbarians - Scythians, Germans - were widely involved in military service. There were a lot of Franks at court, and Constantine was the first to open access to high positions for the barbarians. However, in Rome, the emperor felt uncomfortable and in 330 founded the new capital of the state - New Rome - on the site of the Greek trading city of Byzantium, on the European coast of the Bosphorus. After some time, the new capital became known as Constantinople. Over the years, Constantine gravitated more and more towards luxury, and his court in the new (eastern) capital was very similar to the court of the eastern ruler. The emperor dressed in colorful silk robes embroidered with gold, wore false hair and walked around in gold bracelets and necklaces.

In general, the 25-year reign of Constantine I passed peacefully, except for the church turmoil that began under him. The reason for this turmoil, in addition to religious and theological disputes, was that the relationship between the imperial power (Caesar) and the Church remained unclear. While the emperor was a pagan, Christians resolutely defended their inner freedom from encroachment, but with the victory of the Christian emperor (albeit not yet baptized), the situation changed fundamentally. According to the tradition that existed in the Roman Empire, it was the head of state who was the supreme arbiter in all disputes, including religious ones.

The first event was a schism in the Christian Church of Africa. Some believers were unhappy with the new bishop, as they considered him connected with those who renounced the faith during the period of persecution under Diocletian. They chose another bishop for themselves - Donat (they began to be called pre-natists), refused to obey the church authorities and turned to the court of Caesar. "What folly to demand judgment from a man who himself awaits the judgment of Christ!" exclaimed Konstantin. Indeed, he was not even baptized. However, wanting peace for the Church, the emperor agreed to act as judge. After listening to both sides, he decided that the Donatists were wrong, and immediately showed his power: their leaders were sent into exile, and the property of the Donatist Church was confiscated. This intervention of the authorities in the intra-church dispute was contrary to the spirit of the Edict of Milan on religious tolerance, but was perceived by everyone as completely natural. Neither the bishops nor the people objected. And the Donatists themselves, victims of persecution, did not doubt that Constantine had the right to resolve this dispute - they only demanded that persecution befall their opponents. The schism gave rise to mutual bitterness, and persecution gave rise to fanaticism, and real peace did not come to the African Church very soon. Weakened by internal unrest, this province in a few decades became an easy prey for vandals.

But the most serious split occurred in the east of the Empire in connection with the dispute with the Arians. Back in 318, a dispute arose in Alexandria between Bishop Alexander and his deacon Arius about the person of Christ. Very quickly, all Eastern Christians were drawn into this dispute. When in 324 Constantine annexed the eastern part of the Empire, he faced a situation close to schism, which could not but depress him, since both as a Christian and as an emperor he passionately desired church unity. "Give me back peaceful days and calm nights, so that I can finally find solace in the pure light (i.e. - the one Church. - Note. ed,)", - he wrote. To resolve this issue, he convened a council of bishops, which took place in Nicaea in 325 (I Ecumenical or Nicean Council 325).

Constantine received the 318 bishops who arrived solemnly and with great honor in his palace. Many bishops were persecuted by Diocletian and Galerius, and Constantine looked at their injuries and scars with tears in his eyes. The minutes of the First Ecumenical Council have not been preserved. It is only known that he condemned Arius as a heretic and solemnly proclaimed that Christ is consubstantial with God the Father. The council was chaired by the emperor and resolved a few more issues related to worship. In general, for the entire empire, this was, of course, the triumph of Christianity.

In 326 Constantine's mother Helen made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, where the cross of Jesus Christ was found. On her initiative, the cross was raised and slowly turned to the four cardinal points, as if consecrating the whole world to Christ. Christianity has won. But peace was still very far away. The court bishops, and above all Eusebius of Caesarea, were friends of Arius. At the council in Nicaea, they agreed with his condemnation, seeing the mood of the vast majority of bishops, but then they tried to convince the emperor that Arius was condemned by mistake. Constantine (who had not yet been baptized!), of course, listened to their opinion and therefore returned Arius from exile and ordered, again resorting to his imperial power, to accept him back into the bosom of the Church (this did not happen, since Arius died on the way to Egypt). All the irreconcilable opponents of Arius and the supporters of the Council of Nicaea, and above all the new Bishop of Alexandria Athanasius, he sent into exile. This happened in 330-335.

The intervention of Constantine led to the fact that the Arian schism stretched out for almost the entire 4th century and was eliminated only in 381 at the II Ecumenical Council (Council of Constantinople in 381), but this happened after the death of the emperor. In 337, Constantine felt the approach of death. All his life he dreamed of being baptized in the waters of the Jordan, but political affairs interfered with this. Now, on his deathbed, it was no longer possible to postpone, and before his death he was baptized by the same Eusebius of Caesarea. On May 22, 337, Emperor Constantine I died in the Aquirion Palace, near Nicomedia, leaving three heirs. His ashes were buried in the Apostolic Church in Constantinople. Church historians called Constantine the Great and proclaimed him a model of a Christian.

The significance of Constantine I the Great is enormous. In fact, a new era began with him both in the life of the Christian Church and in the history of mankind, which was called the “epoch of Constantine,” a complex and contradictory period. Constantine was the first of the Caesars to realize all the greatness and all the complexity of the combination of the Christian faith and political power, the first to try to realize his power as Christian service to people, but at the same time he inevitably acted in the spirit of the political traditions and customs of his time. Constantine gave the Christian Church freedom by releasing it from the underground, and for this he was called equal to the apostles, but nevertheless he too often acted as an arbiter in church disputes, thereby subordinating the Church to the state. It was Constantine who first proclaimed the high principles of religious tolerance and humanism, but could not put them into practice. The "thousand-year epoch of Constantine" that began further will carry all these contradictions of its founder.