The meaning of arrian, flavius in the collier's dictionary. Arrian flavius Arrian historian

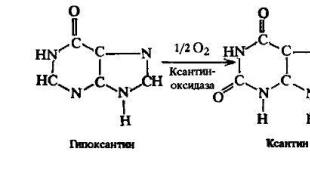

Ancient historians paid great attention to the tactics of the Hellenistic era. Flavius Arrian's Tactics differs from similar works by Asklepiodotus and Elian in that the author has practical experience in the art of war. In his works on military history, Arrian relies not only on the works of previous writers, but also on the events in which he was directly involved. It is quite possible that when writing Tactics, Arrian used the lost work of the same name by Polybius. In Tactics, Arrian describes in sufficient detail the armament and classification of the combat arms, the formation and maneuvers of the phalanx. This book, otherwise called "Tactical Art", in addition to the tactics of the times of Hellenism, contains a treatise on the contemporary author of the Roman cavalry. Completely cite the work of Arrian, translated by S.M. Perevalov. does not allow the format of articles, therefore the text is significantly reduced. Fragments of the Tactics will certainly be interesting and useful to those wargamers and game designers who seriously study weapons and military affairs, not limited to the movement of soldiers' figures and dice rolls.

Flavius Arrian, Tactics

Both foot and horse formations and weapons are varied and varied. So, the armament of the infantry, if divided into the largest [varieties], is divided into three: hoplite, psils and peltasts. Hoplites, the most heavily armed [variety], have shells, shields - round (aspis), or oblong (dash), short swords (mahair) and spears (dorats) - like the Hellenes, or saris - like the Macedonians. Psils have all the [weapons] exactly the opposite of the hoplites, since they have no shell, shield, greaves or helmet, and use long-range weapons: arrows from a bow, darts, slings, stones [thrown] by hand. Peltasts are lighter armed than hoplites - after all, a pelt is smaller and lighter than a round shield, and darts (acontia) are shorter than spears and saris - but heavier than psils. Correctly and heavily armed hoplites are given a helmet, or felt hats - Laconian, or Arcadian, [two] knemids - like the ancient Hellenes, or, - like the Romans, one knemis for that leg that is put forward in battles, and the shells are scaly or woven from thin iron rings.

The armament of the cavalry is either armored (cataphract), or non-armored (afract). Cataphract [weaponry] - that which provides armor protection for both horses and horsemen, and the [horsemen] themselves - with scaly, linen or horny carapaces, as well as legguards, and horses - with ribs and foreheads; afractal [weaponry] is just the opposite. Among them, on the one hand, there are spear-bearers (doratophors) - either pike-bearers (contophores), or lonchophores, on the other - truckers (acrobolists), [of whom] there is only one species. Spearmen are those who, approaching the battle formations of the enemies, fight either with spears (dorats), or with pikes (contos), rushing into the attack, like the Alans and Savromats; acrobolists act with projectiles from afar, like Armenia and the Parthians from those who are not contophores. Of the [horsemen] of the first type, some wear [oblong] shields (dashes) and are called shield-bearers (thyrophores), others [do] without them and fight in the same way, but with spears (dorats) and contes, they are called spear-bearers themselves (doratophores) or contophores, among them there are also xystophores. Acrobolists could be called those who do not converge hand-to-hand, but shoot and throw at a distance. Of these, some use small spears (doration) for shelling, others use bows. [Acrobolists] who fire with small spears are called Tarentines, others are horse archers (hippotoxots). Among the Tarentines themselves, some carry on such a bombardment, by all means keeping [from the enemy] at a distance, or forming a circle when they jump — they are the real Tarentines; others first throw, and then engage in battle with opponents, either with one remaining spear, or using a long sword (spata), and they are called "light" (elaphrs). Among the Romans, some horsemen wear contes and attack in the manner of the Alan and Sauromats, while others have spear-lance (lonchs). A large and wide sword (spata) hangs from their shoulders, they wear wide and oblong shields (dashes), an iron helmet, a forged carapace and small leggings. Spears (lonhi) are worn for both purposes: both in order to throw them from a distance, when necessary, and in order to fight close, [holding them] in hand, and if it is necessary to come together [with the enemy] close hand-to-hand, then fight with swords (spats). Some also carry small axes with blades rounded on all sides.

Each equestrian or foot formation has its own composition, leaders, numbers and names so that [you can] quickly accept orders: this should now be discussed. The first and most important thing in the art of a commander is to take the [just] recruited and disorganized mass of people, place them in the proper formation and order: [that is] distribute among the suckers and group the suckers, establish a proportional and suitable number for battle for the entire army. Loch is the name of [a certain] number of people, from the leader and built behind him in depth down to the last, which is called "closing" (hurricane). Some set the number of the sucker at eight, some at ten, some [add] two to ten, and some at sixteen. We will take the greatest depth at sixteen [people]. This [number] will be commensurate with both the length of the formation and the depth of the phalanx, and also [suitable] for shooting bows or throwing over the [phalanx] from the side of the psils attached to it from behind. And if it is necessary to double the depth to thirty-two husbands, such a construction remains proportionate; and even if the front (metopon) stretches, [reducing the depth] to eight [husbands], the phalanx does not completely lose the depth [of construction]. But if you want to stretch [the phalanx] from eight to four, then it will lose depth. So, a lohag, since from him, as from the first, a goof begins to build, you need to choose the strongest: he is also called the "forward" (protostat) and leader (hegemon). The one behind the lohag is called the “backward” (epistatus), the one after him is the “forward” (protostat), the one behind him is [again] the epistatus, so that the entire row of the sucker is made up of protostats and epistats, standing alternately. It is necessary that not only the lohag be the strongest of the sucker, but also the hurricane is chosen not much weaker: after all, many and no less important combat missions are entrusted to him. So, let the sucker be a row of epistats and protostats, lined up between the sucker and the hurricane.

The entire aggregate structure of the army is called the phalanx; its length could initially be considered a line of lohags, which some call the front (metopon), but there are those who [call] the face (prosopon) and the line (jugon), and there are also those who [call] the same [formation ] jaws (stoma), and others by the "front line of suckers" (protolochia). Everything behind the length, up to hurricane, is called depth. And the arrangement in a straight line [line] in length of the protostats or epistats is called "lining up" (sujugain), while "lining up" (stohein) means [arrangement] in the depth in a straight line between hurricane and lohags. The phalanx is divided into two large parts by dividing the entire front in two along the entire depth. The half of it that [is] on the right is called the right “flank” (keras) and “head” (kefale); the one on the left - the left flank and "tail" (uras). The [place] where the bifurcation occurs is called the “navel” (omphalus), the jaws (stoma), and the bow (araros).

Psils are usually built behind the hoplites, so that they themselves have protection from hoplite weapons, and for the hoplites, in turn, benefit from the throwing from behind. However, when it is necessary, the psils are also located in another place: on both flanks, or, if there is a [natural] obstacle on any one flank: a river, ditch or sea, - only on one [opposite flank], and on dominant height in order to repel an attack in this place of enemies, or to prevent encirclement. Also, the battle formations of the cavalry are placed here and there, so that their location is dictated by usefulness. It is not [the business] of the commander to determine the size of the composition necessary for the army as a whole: however, whatever it may be, he should be taught the formation, exercises and [art] of a quick transition from one formation to another. [Regarding] the number: I would nevertheless advise the commander of the entire [possible] composition to bring into battle such a number that will be convenient for changing battle formations and their regrouping, such as doubling and multiplying, or the same order of decreasing [ranks], or [for] counter-marches (exceligma), or for any other changes in battle formations. Therefore, those who are versed in such things preferred, of all numbers, mainly those numbers that are divisible in two to one: for example, the order of sixteen thousand three hundred and eighty-four, if it concerns hoplites; half of this amount is for psils, and half of the previous one is for horsemen. This number is indeed divisible in half to one, so it is easy to arrange it so that it quickly doubles when collapsing [construction], and when expanded, on the contrary, stretches when necessary. For example, when we set a depth of sixteen men for a sucker, the suckers with this number will be one thousand twenty-four, and they are divided into groups, each of which is given its own name.

Two suckers are called dilochia, out of thirty-two people, and their commander diliohit; four suckers - tetrarchy, and its commander - tetrarch, chief of sixty-four husbands. Two tetrarchies are taxis, there are eight suckers, and a hundred and twenty-eight men, and their commander is a taxiarch. When a unit consists of a hundred, its commander is called accordingly - a centurion (hecatontarch). Two taxis are called syntagma, sixteen suckers, two hundred and fifty-six husbands, and its commander, respectively, is a syntagmatarch. Some call her the xenagia and the xenagus of her commander. For each unit of two hundred and fifty-six [people] there is a selected standard-bearer, hurricane, trumpeter, orderly (hypereth), military herald; the whole syntagma, built by a square, has sixteen [persons] both in length and in depth. The two syntagmas make up [the number in] five hundred and twelve men and thirty-two suckers, and their commander is the pentakosiarch. When it is doubled, a chiliarchy is formed, there are one thousand twenty-four men, sixty-four suckers, and a chiliarch above it. Two chiliarchies - a hierarchy, of two thousand forty-eight people, and its chief is a hierarch, one hundred twenty-eight suckers; some call it telos. Two hierarchies - the phalangarchy, of four thousand ninety-six people, two hundred and fifty-six suckers, and its commander, respectively, is the phalanx. Some call it a strategy, and a commander a strategist. Two phalangarchies - diphalangia, out of eight thousand one hundred ninety-two husbands, five hundred and twelve suckers. This unit is the same as the “unit” (meros) and the “flank” (keras). Two diphalangia are called tetrafalangia, which consists of one thousand twenty-four suckers, [and] sixteen thousand three hundred and eighty-four men, the very total number that we have established for the infantry formation, and it would have two flanks, four phalangarchies, eight hierarchies, chiliarchies sixteen, pentacosyarchies thirty-two, syntagmatarchies sixty-four, taxicarchies one hundred twenty-eight, tetrarchies two hundred fifty-six, dilochias five hundred and twelve, suckers one thousand twenty-four - sequentially.

The phalanx is built in length, where it is necessary to build it more rarefied, if it is expedient for the conditions of the terrain, in depth - where [it is necessary to build] it more dense, if it is necessary to throw off the enemies with cohesion and pressure - as Epaminondas built his Thebans under Leuctra, and under Mantinea - all the Boeotians, forming a semblance of a wedge and leading them to the Lacedaemonians' formation - or, if the attackers have to be repulsed, as it is necessary to build against the Sauromats and Scythians. "Compaction" (pycnosis) is a contraction from the rarer to the denser [structure] along the parastats and epistats, both in length and in depth; "Closing shields" (synaspism) - when you tighten the phalanx to such an extent that the tightness does not allow you to turn the formation in any direction. And on the model of this synaspism, the Romans make a "turtle", mostly square, sometimes round or versatile, depending on the circumstances. Placed on the outer ring of a square or circle, they put up shields in front of them, those standing behind them raise them above their heads, overlapping one [shield] with another. And the entire [formation] is so reliably covered that the projectiles falling from above roll down like on a roof, and even cart stones do not destroy the ceiling, but, having rolled, fall under [their own] weight to the ground.

It is good, among other things, for the suckers to be the tallest, strongest and most experienced in military affairs; for their line keeps [in line] the entire phalanx, and in battles it has the same meaning as the blade of a sword: the latter acts in the same way as all iron weapons. After all, his blow is made precisely by the [hardened] blade, but the rest of the part, even if it is not hardened and soft, still strengthens the blow by its weight; Likewise, someone can consider a line of suckers as the blade of a phalanx, and the army standing behind them as a mass and a weight. It is necessary that the second in valor after the suckers themselves were their epistats: after all, their spear reaches the enemies and they reinforce the onslaught of those who are pushed forward just in front of them. And some people can reach the enemy with a mahaira, striking a blow over the one standing in front of the [lohaga]. If the advanced [warrior] falls or, being wounded, becomes incapable of combat, then the first epistatus, jumping forward, takes the place and position of the lohag, thereby preserving the integrity [of the battle order] of the entire phalanx. The third and fourth ranks should be built, choosing the distance from the first [rank] according to the calculation. From this, the Macedonian phalanx seemed terrible to the enemies not only in deeds, but also in appearance. After all, a hoplite warrior is at most two cubits apart from the others [in a line] in a dense formation (pycnosis), while the length of the sarisa was sixteen feet. Of these, four [feet] extended [behind] to the hand of the holder and the rest of his body, and twelve extended in front of the torso of each of the protostats. The [hoplites] of the second rank, two feet apart from the previous ones, had saris protruding ten feet beyond the protostats, as for the [hoplites] in the third rank, they also raise [the saris] above the protostats eight feet in advance. And the [hoplites] of the fourth [rank] - by six, the fifth - by four, the sixth by two. Thus, in front of each of the protostats, six saris are displayed, arcing backward, so that each hoplite is covered by six saris and, when rushing [forward], presses with sixfold force. Those placed behind the sixth [rank] push — if not with the saris themselves, then with the weight of the bodies — together with those who stand in front of them, so that the onslaught of the phalanx on the enemies becomes insurmountable, and also prevent the protostats from escaping. Urags should be chosen not so much by strength as by their intelligence and experience in military affairs, so that they take care of aligning the ranks and would not allow deserters to leave the battle formations. And when it is required to [form] a synaspism, it is he [hurricane], mainly, that brings those in front of it into a dense formation, and provides full strength to this formation.

,Whose philosophical conversations he wrote down and published.

Arrian wrote historical treatises, for example, about India ("Indika"), about the life and campaigns of Alexander the Great ("Anabasis Alexandru"). A passionate dog hunter, Arrian wrote the book On Hunting.

Links

- Arrian of Nicomedia

Arrian's writings

- Arrian. "Walk of Alexander" ("Anabasis Alexandru").

- Arrian. "India" ("Indika").

- Arrian. "Bypass Euxine Pontus" ("Periplus").

- Fragment (in English) from Photius based on Arrian's book "Events after Alexander".

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.

- Flavian of Constantinople

- Flavius Dalmatius

See what "Flavius Arrian" is in other dictionaries:

Arrian- Lucius Flavius Arrian lat. Lucius Flavius Arrianus Occupation: Historian Date of Birth: about 89 Places ... Wikipedia

ARRIAN Flavius- (between 95,175) Ancient Greek historian and writer. The author of the surviving Anabasis Alexander in 7 books (the history of the campaigns of Alexander the Great), India, philosophical writings (in which he expounded the teachings of Epictetus), treatises on military affairs and ... ... Big Encyclopedic Dictionary

Arrian Flavius- Arrian (Arrianys) Flavius (between 95-175), ancient Greek historian and writer. Born in Nicomedia (M. Asia). Studied in Greece under the Stoic philosopher Epictetus. He held a number of government posts (in 121-124 he was consul) in Rome. About 131-137 ... ... Great Soviet Encyclopedia

Arrian- Flavius (Arrianus) one of the prominent Greek writers during the Roman Empire; genus. in Nicomedia, in Bithynia. Under Hadrian, he reached the consulate, and from about 130-138. was the governor in Cappadocia, then, however, retired from business to his ... ... Encyclopedic Dictionary of F.A. Brockhaus and I.A. Efron

Arrian- Flavius (c. 95 2nd half of the 2nd century AD) Old Greek. historian and writer. Genus. in M. Asia in the city of Nicomedia. Studied in Greece under the Stoic philosopher Epictetus. Lived in Rome, where he studied military. case. OK. 131 137 the governor of Cappadocia, repelled the attack of the Alans. ... ... Ancient world. encyclopedic Dictionary

Arrian- Flavius, from Nicomedia in Bithynia (c. 95 175), Rome. imperial officer, consul, governor of Cappadocia. A. was a student of Epictetus, whose philosophical conversations he wrote down and published. In addition, A. wrote a historian. treatises, for example about India ("Indika") ... Dictionary of antiquity

ARRIAN Flavius- (Flavius Arrianus) (c. 95 c. 180 AD), an ancient Greek historian originally from Nicomedia (Bithynia in Asia Minor). Arrian's father belonged to the local nobility and was a Roman citizen. Arrian was a listener to the philosopher Epictetus, who lived in Nicopolis (Epirus), ... ... Collier's Encyclopedia

Arrian Flavius- (between 95 and 175), ancient Greek historian and writer. The author of the surviving "Anabasis of Alexander" in 7 books (the history of the campaigns of Alexander the Great), "India", philosophical writings (in which he expounded the teachings of Epictetus), treatises on military affairs ... ... encyclopedic Dictionary

ARRIAN- (Arrianos), Flavius (c. 95 2nd half of the 2nd century AD) other Greek. historian and writer. Genus. in M. Asia in the city of Nicomedia. Studied in Greece under the Stoic philosopher Epictetus. Lived in Rome, where he studied military. case. OK. 131,137 governor of Cappadocia, repelled the attack of the Alans ... Soviet Historical Encyclopedia

Arrian, Flavius- (Greek Arrianos) (c. 95 175 AD) Roman statesman and historian, was born into a noble family in Nicomedia, received a good education; disciple of the famous Stoic philosopher Epictetus. A. traveled a lot, visited Athens and Rome. At 131 ... The ancient world. Reference dictionary.

Books

- Tactical art, Arrian, In a work entitled "Tactical Art" the famous historian II century. n. e. Flavius Arrian examines Greco-Macedonian military affairs: types of troops, battle formations, weapons and maneuvers, and in ... Category: Theory and history of military art Series: Fontes scripti antiqui Publisher:

Current page: 1 (the book has a total of 26 pages)

Quintus Eppius Flavius Arrian

Alexander's hike

Arrian and his work "Alexander's Campaign"

In this article, we try to orient the reader on issues related to the life and work of Arrian, and dwell on those passages of his work on the Campaign of Alexander, which require special comments. The fact that the article is partially in the nature of comments causes some fragmentation of its parts.

The literature on this issue is immense, so only a few links to those books to which we are closest are provided.

Age of Hellenism

Interest in the era of Alexander the Great grows as more and more written and material data are discovered that illuminate the life and history of those countries that were once part of his state. This era stands in the midst of that difficult historical period for research, which is called the time of Hellenism. We are still not able to clearly imagine what are the features of that time, when it begins and how long it lasts. For ancient historians, and for historians of the 19th century, this segment of history begins with the time of Alexander. The famous historian Droysen put it as follows: "The name of Alexander means the end of one world era, the beginning of another." 1

U. Wilcken. Griechische Geschichte im Rahmen der Altertumsgeschichte. Berlin, 1958, p. 245.

The Hellenistic period, however, began long before Alexander the Great.

Hellenistic time differs in many ways from the time of the classical period. Large-scale land tenure is developing. The movement of slaves is increasing. Trade ties between states are expanding. The presence of large territorial states is characteristic. City-states are being reborn into capitals, into "royal cities". The monarchy is spreading everywhere. Alien conquerors are increasingly mixing with the aborigines and gradually losing their first role in the social life of the conquered countries. As a result of such a mixture, a new culture appears, a science that is based on the richest research of Aristotle. If before him science was to a large extent part of philosophy, then after the great thinker certain scientific disciplines are freed more and more from the tutelage of philosophy. Therefore, they develop, become more vital and more in line with the needs of human life. Literature and art receive new content. A man, his life, his character traits give, starting with the tragedian Euripides, the plots of a new comedy. Sculpture studies the structure of the human body, more and more acquiring a portrait resemblance. Various branches of science and technology flourish. Such a socio-ecocomic structure will be created, which was the foundation for the Roman Empire. This complex process, the social nature of which is still far from being explored, spreads throughout the Greek world and far beyond it. Hellenism also established itself on the territory of the Bosporus kingdom. However, there are fewer such eloquent monuments, which abound in Egypt and which are found more and more in Asia.

Alexander's campaign to the east is one of the manifestations of Hellenism. He made such a great impression on ancient historians that they considered him the key to the beginning of a new era. This campaign made it possible for the Macedonians and Greeks to get acquainted with unknown or little-known tribes and nationalities, their way of life and culture. Alexander was personally very interested in studying distant Asia with a way of life so alien to the Greeks. And he was surrounded by talented scientists who, in their books, described in detail everything they saw and studied during the campaign. Military disciplines made a big leap forward: tactics and strategy, issues of supplying the army, ensuring communications of troops (building roads, bridges), organizing the rear. In connection with the pursuit of a broad policy of conquest and the expansion of the scale of state activity, the task of organizing the management of the conquered territories arises, as well as the need to find forms of intercourse with foreign states. A special task arose in the field of navigation: it became necessary to adapt Greek ships to sail in the open and stormy seas washing the southern coast of Asia from India to Arabia. Many new problems faced Alexander and his staff during this campaign. therefore, it is not surprising that the personality of Alexander aroused more and more interest. They began to attribute to him innovations and discoveries that were by no means the fruit of his own creativity. He borrowed a lot from the population of the conquered territories, a lot was found and invented by those prominent figures on whom he relied.

Alexander's contemporaries were divided into admiring supporters who adored him, and persons who condemned the campaign, associated with great human sacrifices and ruin. Among his closest friends and co-workers were those who knew how to sensibly appreciate the activities of Alexander, to really weigh his positive and negative actions. Their opinions are especially valuable for historians, and the more we understand through the thickness of literary layers their views, the easier it is to recreate the historical role of Alexander.

Study of the campaign of Alexander the Great in the XX century. entered a new phase 2

W. W. Tarn. Alexander the Great. I – II. London, 1948.

Archaeological studies of the places where the Macedonian troops marched are increasingly shedding light on the history of the tribes that once inhabited these areas. At the same time, we learn a lot to clarify the important details of this campaign: what organizational forms Alexander borrowed from local states for the establishment of policies and for the organization of troops, cult issues that Alexander had to reckon with, etc. In this regard, and a wonderful monument "Alexander's Campaign" as narrated by Arrian becomes clearer.

The historian studying the era of Alexander has at his disposal many monuments: coins, architectural monuments, household monuments, papyri, parchments. There are more and more of them every year. There are also a number of literary texts. Plutarch, Diodorus, Strabo, and many others also wrote about Alexander. All of them have their own tendencies, all in one way or another distort the legend about the Macedonian commander or reflect his appearance distorted by the sources used. Among these literary monuments, the already mentioned "Walk of Alexander", written by the inquisitive Flavius Arrian, stands out.

Arrian's life and work

Arrian was born in Bithynia, in Asia Minor. The year of birth is not known exactly, apparently around 90–95, but died presumably in 175 AD. e. His hometown is Nicomedia, which played a significant role in the history of Rome. Bithynia was at that time a wealthy Roman province with a large number of Greek inhabitants, aspiring, as in other Roman provinces, for a Roman administrative and military career. The inscriptions found in Bithynia tell a lot about these persons and such, for example, writers as Dion, a famous rhetorician from the city of Prusy in Bithynia (approximately 40-120), Pliny the Younger, who corresponded with Emperor Trajan during his travels around Bithynia, other.

He came from a fairly prominent family. Cassius Dpon Kokceian (about 155–235) from the Bithinian Nicaea wrote his biography, but it has not reached us. Therefore, our information about him is only speculative. 4

By the way, Arrian's biographer is related to the aforementioned Dion from Prusa. It is possible that Cassius Dion wrote a biography of his fellow countryman, prompted by a personal acquaintance. Complicated generic name - Eppius Flavius - the result of adoption.

His family began to be called Flavius, along with many other wealthy Bithynian families during the reign of the Flavian emperors, that is, from the second half of the 1st century. n. e. The time when the family or her ancestors received Roman citizenship is difficult to indicate with certainty, perhaps under the same Flavias. It is known that Emperor Vespasian, the founder of the Flavian dynasty, showed great interest and goodwill towards the provincial aristocracy and opened her access to the senatorial estate, having previously endowed her with Roman citizenship 5

N. A. Mashkin. History of Rome. M., 1947, p. 432.

Arrian received an excellent Greek education. Speaking Greek and Roman, he was an extremely convenient person to represent Roman interests in Greek cities. Like all the youths of his circle who were about to make their way into Roman society, he received a good training in the field of rhetoric and philosophy. As a writer, he imitated Xenophon (430–355 BC), a famous student of Socrates. The versatile subject matter of Arrian's writings puts this beyond any doubt. But it seems that both his upbringing and training were built according to this scheme, widespread in the eastern cities of the ancient world. Like Xenophon, he was prepared for a career in military practice, just like Xenophon, he studied eloquence and philosophy. His rhetorical art is illustrated by speeches included in Alexander's Campaign. Arrian's philosophical ideal was Epictetus (approximately AD 50-133). With him, Arrian, apparently, studied in Nicomedia between 112 and 116. This representative of ethical philosophy gained great fame for his teachings, and in addition, he made a great impression on his contemporaries and the way of his life. If Xenophon studied with Socrates and considered it a moral duty to glorify him in his writings, then Arrian did the same in relation to his beloved teacher Epictetus. Like Socrates, Epictetus himself did not write a single line. He was born a slave and began his philosophical career as a representative of the ancient stand. At first, his teachings incurred the hatred of influential Romans, and at the end of the 1st century. n. e. he was expelled from Italy, where he had many supporters, and he settled in the city of Nikopol in Epirus. His teaching of mature years for a long time became the official worldview of the Roman military nobility. Of the philosophical disciplines, he gave preference to ethics, and did not pay attention to physics and logic. In his ethical teaching, there are many thoughts similar to Christianity of the time when it was still the spokesman for some social protest from the lower strata of the Roman slave-owning society. Arrian was so carried away by his teacher that he wrote down the "Conversations of Epictetus" and the "Manual on the Doctrine of Epictetus", apparently without seeking to publish them. The language of these notes is simple, easily accessible to the reader. Probably, Arrian transmitted the teachings of Epictetus, without subjecting his memories to literary processing. This is how his book differs significantly from the "Memoirs of Socrates" and other books about him written by Xenophon and Plato. In these books, the literary side of the story was so dominant that the factual basis receded into the background. The historical image of Socrates cannot be restored from them.

The philosophy of Epictetus, especially popular in the 2nd century, asserted that wise and just providence reigns in the universe. This gave the teachings of Epictetus the character of a monotheistic religion, which the Roman state needed during the period of the empire. He was even supported by some emperors, such as the famous "philosopher on the throne" Marcus Aurelius 6

W. Christ-Schmid. Geschichte der griechischen Literatur, II, 2. München, 1924, p. 830 et seq. This guide contains the most reliable historical and literary data.

According to the teachings of Epictetus, a person must unquestioningly submit to providence and discard everything that can distract him from peace of mind. It is necessary to improve in such a way as to "abstain and endure." The best way to calm the soul - "healing" the soul - is philosophy. The focus on self-improvement was supposed to help divert attention from struggles, especially political ones. This goal was served by the teaching of Epictetus at all times.

As already mentioned, Arrian did not set himself the goal of making a literary work from the records of the teachings of Epictetus. However, they became the property of a wide range of readers, but without the knowledge of the author. Arrian was compared to Xenophon, they even called him "the new Xenophon." The similarity of their subject matter was probably the main reason for this comparison. After his philosophical treatises, Arrian writes about travel and military affairs, as Xenophon did. From our point of view, Arriana should be considered a greater specialist in this area than Kssnophon. From a young age he was well trained in military science both theoretically and practically. The description of the countries clearly reveals in him a specialist-strategist: it is not the beauty of the described places that seduces him, but their importance as strategic points. In our tradition, Arrian opens this kind of work with a description of the Black Sea coast. An accurate knowledge of the area was essential for Roman expansion. This "Description" falls into three parts. The first part he addresses to the Emperor Hadrian; it tells the story of Arrian's visit to the Black Sea, before being received by him in 131 on behalf of the emperor. The second part is stingy with descriptions, it only talks about the distances between points on the coast from the Thracian Bosporus to Trebizond. The third part contained a description of the journey from Sebastopolis (Dioscuriada) to Byzantium. All three parts served different purposes. If the first satisfied more general geographic interests, the other two pursued practical goals; they were navigational guides. In ancient times, the description of such routes was very common. They were used by sailing merchants who set off to unknown countries. They were of particular importance for naval campaigns, giving an idea of where garrisons should be deployed in the newly conquered countries.

Another work, once attributed to Arrian, has survived under the title Travels along the Coasts of the Red Sea. Apparently, the same title and the same plot forced them to be attributed to the same author. And the description of the Red Sea contains a thorough description of the port sea points. This is a very valuable work. It indicates everything that a merchant-sailor needs to know during a long "walk" in the Red Sea, along the shores of southern Arabia, India, etc. However, along with the information that was known to the author from his own observation, there are also fantastic reports, which, perhaps, he himself did not believe, but did not dare to throw away. This kind of literature found imitators at a much later time. However, philological science long ago abandoned the idea of considering Arrian the author of the description of the Red Sea: this is not allowed by both the stylistic manner alien to him, and the peculiarities of his language.

After completing his studies in philosophy with Epictetus, Arrian devotes himself entirely to serving the Roman state. An inscription accidentally discovered mentions Arrian among the imperial delegates in Greece under the command of Avidius Nigrin. This dates back to 116 BC. 7

W. Dittenberger. Sylloge inscriptionum graecarum, Bd. 2. Leipzig, 1918, p. 538.

Then he was, apparently, already a senator. The task of the commission was to determine the exact boundaries of the "sacred" land of the Delphic temple. The office work was carried out in Greek and Latin. This is a small illustration of how the emperors recruited officials from Greek cities for this kind of business. In the years 121-124, Emperor Hadrian conferred on Arrian the rank of consul 8

W. Christ-Schmid, c. cit., II, 2, p. 746.

From 131 to 137, he, as the personal legate of the emperor, ruled the province of Cappadocia, a place of great responsibility. Cappadocia was then subjected to continuous attacks from the Alans, and the emperor Hadrian was forced to send there a person experienced in military affairs. Apparently, the choice was made well. This can be concluded from the very lively judgments about military issues included in Arrian's story about Alexander's campaign. Arrian received solid practical knowledge of military affairs while in the civil service, participating in campaigns. However, we have no data to clarify. By reasoning, we can still form a definite opinion about the knowledge of Arrian. Without his own experience, Arrian would not have been able to understand the sources he used when working on Alexander's Campaign. Remarks about the battle at Gaugamela and in other points, about the battle formations of Alexander's troops, the preference of some sources for others testify not only to Arrian's common sense, but also to his deep knowledge. From the characteristics of the geographical features of Istra, the Inn and Sava rivers, we can conclude that he once visited here 9

Arrianus. Indica, 4.15.

Arrian's remark about how the Romans built bridges is especially characteristic.

The researcher Arrian, analyzing the corresponding place in his work, involuntarily faces the question: did Arrian judge this or that problem only by the sources, or, borrowing reasoning from the source, adds his remarks, or, finally, illuminates the problem based on his own observations, as an eyewitness ...

Arrian's work admits only this latter interpretation. This is supported, firstly, by the fact that the remark about the methods of building bridges by Roman soldiers here interrupts the story of Alexander's progress. The impetus for this logical retreat was given by thinking about that. how Alexander threw a bridge over the Indus River. Arrian knows two kinds of bridges: permanent bridges and temporary bridges. He believes that Alexander was unlikely to build the bridge in the same way as bridges were built at Darius across the Danube or at Kssrkss across the Hellespont. Arrian writes: “... or the bridge was built in the way that, if necessary, the Romans use on Istria, on the Celtic Rhine, on the Euphrates and the Tigris. The fastest way to build bridges among the Romans, I know, is to build a bridge on ships; I'll talk about how it's done now, because it's worth mentioning. " 10

Arrian. Alexander's Campaign, V.7.2–3.

In the first part of the above passage, Arrian used the testimony of Herodotus, and the story of Roman bridge building is presented in such a way that one has to consider it a memory from his own practice. The final phrases are especially interesting: “Everything ends very quickly, and, despite the noise and rumbling, the order in the work is observed. It happens that encouraging cries of encouragement are heard from each ship and abuse is poured on those who lag behind, but this does not interfere with either following orders or working with great speed. " 11

Ibid, V.7.5. Caesar can be compared with this account (Bellum Gallicum. IV. 17).

This description seems to show us the warlord Arrian, surrounded by working sappers, who encourages them by shouting or scolding. He could not read this detail in any source. It is felt that the old officer recalls with some excitement a case from his practice of hurriedly building bridges, i.e. crossings across the Rhine and Istres, the Euphrates and the Tigris during hostilities. These considerations of ours lead us to assume that at some stage of his life he participated in the indicated places in hostilities. Such campaigns could have taken place during the reign of Hadrian (117–138), when the Romans waged a desperate struggle to preserve the integrity of the empire against the Dacians, Celts and in the east. We know that Arrian was well informed, not only theoretically, from his work on the tactics he wrote, apparently in connection with the governorship in Cappadocia. Questions of tactics were discussed even under Trajan. In 136, the emperor Hadrian commissioned Arrian to compose a new work on this issue. Apparently, Adrian wanted such a book to have the character of a textbook. 12

To train military leaders and to take into account the new tactical views of Adrian himself. This guide is divided into two sections. In the first, Arrian outlined the tactics of the previous period, that is, the Greeks and Macedonians, and the second part explained the meaning and significance of Hadrian's reforms in the field of cavalry tactics. For the first part, Arrian had to use special literature, and in the second part he explains the special terminology. The "History of the Alans", which undoubtedly also arose during the rule of Cappadocia, belongs to the same range of questions. From this book survived a passage "Formation against the Alans", which outlines the difference between Greek and Roman tactics.

From the end of the reign of Hadrian, Arrian is removed from participation in Roman state and military life. The reasons for this are unknown to us. But the termination of state and military service in Rome does not mean a complete retirement from business for Arrian: from now on, he, perhaps, more intensively and more than before, devotes himself to literary activity, and he occupies only local positions. In 147, Arrian was elected as an eponymous archon in Athens and awarded civil rights in the demos of Payania. 13

IG, 3, 1116.

This post had no great political significance: the archon-eponym headed only the college of archons, and the year was named after him - for a narrow circle of Athens. Of course, Arrian could only hold this position with the consent of the Roman emperor. Further, it is also testified that Arrian in Nicomedia was chosen as a priest of the goddesses of the underworld of Demeter and Persephone. No further information on his life path is found.

Arrian's book "On the Hunt" is closely related to Xenophon. It was written in Athens, when Arrian was under the spell of this writer. In this work, he supplements Xenophon's information with information from the hunting practice of the Celts. 12

W. Christ-Schmid, c. cit., II, 2, p. 748.

We have to regret that the biographies of Timoleon and Dion, who interested Arrian as strategists, did not reach us. They would help us, perhaps, to understand more clearly what the peculiarities of Arrian the biographer are. In the II century. n. e. this literary genre has already been developed and represented by a number of major writers, of whom Plutarch is the most famous. What, according to Arrian, was included in the concept of biography, you need to know when studying his "Campaign of Alexander", conceived to a large extent as a biographical work.

Arrian also probably owns the lost biography of the robber Tillobor. 14

Luc. Alex., 2; Cic. de off., II.40.

Literary interest in the biographies of "noble robbers" arises even in pre-Hellenistic times. Theopompus talked about the just robber or prince Bardulis. Cicero, in his treatise on duties, on the basis of the relevant literature, speaks of the organization of the relationship between the robbers. We know little about the reason for the emergence of this topic. The Stoics showed by the examples of these "despicable" people that a person is born with a desire for some order, a desire for ethical standards. Perhaps the Stoic Arrian was interested in their social life precisely from this point of view.

In this article, we try to orient the reader on issues related to the life and work of Arrian, and dwell on those passages of his work on the Campaign of Alexander, which require special comments. The fact that the article is partially in the nature of comments causes some fragmentation of its parts.

The literature on this issue is immense, so only a few links to those books to which we are closest are provided.

Age of Hellenism

Interest in the era of Alexander the Great grows as more and more written and material data are discovered that illuminate the life and history of those countries that were once part of his state. This era stands in the midst of that difficult historical period for research, which is called the time of Hellenism. We are still not able to clearly imagine what are the features of that time, when it begins and how long it lasts. For ancient historians, and for historians of the 19th century, this segment of history begins with the time of Alexander. The famous historian Droysen put it as follows: "The name of Alexander means the end of one world era, the beginning of another." The Hellenistic period, however, began long before Alexander the Great.

Hellenistic time differs in many ways from the time of the classical period. Large-scale land tenure is developing. The movement of slaves is increasing. Trade ties between states are expanding. The presence of large territorial states is characteristic. City-states are being reborn into capitals, into "royal cities". The monarchy is spreading everywhere. Alien conquerors are increasingly mixing with the aborigines and gradually losing their first role in the social life of the conquered countries. As a result of such a mixture, a new culture appears, a science that is based on the richest research of Aristotle. If before him science was to a large extent part of philosophy, then after the great thinker certain scientific disciplines are freed more and more from the tutelage of philosophy. Therefore, they develop, become more vital and more in line with the needs of human life. Literature and art receive new content. A man, his life, his character traits give, starting with the tragedian Euripides, the plots of a new comedy. Sculpture studies the structure of the human body, more and more acquiring a portrait resemblance. Various branches of science and technology flourish. Such a socio-ecocomic structure will be created, which was the foundation for the Roman Empire. This complex process, the social nature of which is still far from being explored, spreads throughout the Greek world and far beyond it. Hellenism also established itself on the territory of the Bosporus kingdom. However, there are fewer such eloquent monuments, which abound in Egypt and which are found more and more in Asia.

Alexander's campaign to the east is one of the manifestations of Hellenism. He made such a great impression on ancient historians that they considered him the key to the beginning of a new era. This campaign made it possible for the Macedonians and Greeks to get acquainted with unknown or little-known tribes and nationalities, their way of life and culture. Alexander was personally very interested in studying distant Asia with a way of life so alien to the Greeks. And he was surrounded by talented scientists who, in their books, described in detail everything they saw and studied during the campaign. Military disciplines made a big leap forward: tactics and strategy, issues of supplying the army, ensuring communications of troops (building roads, bridges), organizing the rear. In connection with the pursuit of a broad policy of conquest and the expansion of the scale of state activity, the task of organizing the management of the conquered territories arises, as well as the need to find forms of intercourse with foreign states. A special task arose in the field of navigation: it became necessary to adapt Greek ships to sail in the open and stormy seas washing the southern coast of Asia from India to Arabia. Many new problems faced Alexander and his staff during this campaign. therefore, it is not surprising that the personality of Alexander aroused more and more interest. They began to attribute to him innovations and discoveries that were by no means the fruit of his own creativity. He borrowed a lot from the population of the conquered territories, a lot was found and invented by those prominent figures on whom he relied.

Alexander's contemporaries were divided into admiring supporters who adored him, and persons who condemned the campaign, associated with great human sacrifices and ruin. Among his closest friends and co-workers were those who knew how to sensibly appreciate the activities of Alexander, to really weigh his positive and negative actions. Their opinions are especially valuable for historians, and the more we understand through the thickness of literary layers their views, the easier it is to recreate the historical role of Alexander.

Study of the campaign of Alexander the Great in the XX century. entered a new phase. Archaeological studies of the places where the Macedonian troops marched are increasingly shedding light on the history of the tribes that once inhabited these areas. At the same time, we learn a lot to clarify the important details of this campaign: what organizational forms Alexander borrowed from local states for the establishment of policies and for the organization of troops, cult issues that Alexander had to reckon with, etc. In this regard, and a wonderful monument "Alexander's Campaign" as narrated by Arrian becomes clearer.

The historian studying the era of Alexander has at his disposal many monuments: coins, architectural monuments, household monuments, papyri, parchments. There are more and more of them every year. There are also a number of literary texts. Plutarch, Diodorus, Strabo, and many others also wrote about Alexander. All of them have their own tendencies, all in one way or another distort the legend about the Macedonian commander or reflect his appearance distorted by the sources used. Among these literary monuments, the already mentioned "Walk of Alexander", written by the inquisitive Flavius Arrian, stands out.

Arrian's life and work

Arrian was born in Bithynia, in Asia Minor. The year of birth is not known exactly, apparently around 90–95, but died presumably in 175 AD. e. His hometown is Nicomedia, which played a significant role in the history of Rome. Bithynia was at that time a wealthy Roman province with a large number of Greek inhabitants, aspiring, as in other Roman provinces, for a Roman administrative and military career. The inscriptions found in Bithynia tell a lot about these persons and such, for example, writers as Dion, a famous rhetorician from the city of Prusy in Bithynia (approximately 40-120), Pliny the Younger, who corresponded with Emperor Trajan during his travels around Bithynia, other.

The full name of the author of Alexander's Campaign is Quintus Eppius Flavius Arrian. He came from a fairly prominent family. Cassius Dpon Kokceian (about 155–235) from the Bithinian Nicaea wrote his biography, but it has not reached us. Therefore, our information about him is only speculative. His family began to be called Flavius, along with many other wealthy Bithynian families during the reign of the Flavian emperors, that is, from the second half of the 1st century. n. e. The time when the family or her ancestors received Roman citizenship is difficult to indicate with certainty, perhaps under the same Flavias. It is known that the emperor Vespasian, the founder of the Flavian dynasty, showed great interest and goodwill towards the provincial aristocracy and gave her access to the senatorial estate, having previously endowed her with Roman citizenship.

Arrian received an excellent Greek education. Speaking Greek and Roman, he was an extremely convenient person to represent Roman interests in Greek cities. Like all the youths of his circle who were about to make their way into Roman society, he received a good training in the field of rhetoric and philosophy. As a writer, he imitated Xenophon (430–355 BC), a famous student of Socrates. The versatile subject matter of Arrian's writings puts this beyond any doubt. But it seems that both his upbringing and training were built according to this scheme, widespread in the eastern cities of the ancient world. Like Xenophon, he was prepared for a career in military practice, just like Xenophon, he studied eloquence and philosophy. His rhetorical art is illustrated by speeches included in Alexander's Campaign. Arrian's philosophical ideal was Epictetus (approximately AD 50-133). With him, Arrian, apparently, studied in Nicomedia between 112 and 116. This representative of ethical philosophy gained great fame for his teachings, and in addition, he made a great impression on his contemporaries and the way of his life. If Xenophon studied with Socrates and considered it a moral duty to glorify him in his writings, then Arrian did the same in relation to his beloved teacher Epictetus. Like Socrates, Epictetus himself did not write a single line. He was born a slave and began his philosophical career as a representative of the ancient stand. At first, his teachings incurred the hatred of influential Romans, and at the end of the 1st century. n. e. he was expelled from Italy, where he had many supporters, and he settled in the city of Nikopol in Epirus. His teaching of mature years for a long time became the official worldview of the Roman military nobility. Of the philosophical disciplines, he gave preference to ethics, and did not pay attention to physics and logic. In his ethical teaching, there are many thoughts similar to Christianity of the time when it was still the spokesman for some social protest from the lower strata of the Roman slave-owning society. Arrian was so carried away by his teacher that he wrote down the "Conversations of Epictetus" and the "Manual on the Doctrine of Epictetus", apparently without seeking to publish them. The language of these notes is simple, easily accessible to the reader. Probably, Arrian transmitted the teachings of Epictetus, without subjecting his memories to literary processing. This is how his book differs significantly from the "Memoirs of Socrates" and other books about him written by Xenophon and Plato. In these books, the literary side of the story was so dominant that the factual basis receded into the background. The historical image of Socrates cannot be restored from them.

The philosophy of Epictetus, especially popular in the 2nd century, asserted that wise and just providence reigns in the universe. This gave the teachings of Epictetus the character of a monotheistic religion, which the Roman state needed during the period of the empire. He was even supported by some emperors, such as the famous "philosopher on the throne" Marcus Aurelius. According to the teachings of Epictetus, a person must unquestioningly submit to providence and discard everything that can distract him from peace of mind. It is necessary to improve in such a way as to "abstain and endure." The best way to calm the soul - "healing" the soul - is philosophy. The focus on self-improvement was supposed to help divert attention from struggles, especially political ones. This goal was served by the teaching of Epictetus at all times.

As already mentioned, Arrian did not set himself the goal of making a literary work from the records of the teachings of Epictetus. However, they became the property of a wide range of readers, but without the knowledge of the author. Arrian was compared to Xenophon, they even called him "the new Xenophon." The similarity of their subject matter was probably the main reason for this comparison. After his philosophical treatises, Arrian writes about travel and military affairs, as Xenophon did. From our point of view, Arriana should be considered a greater specialist in this area than Kssnophon. From a young age he was well trained in military science both theoretically and practically. The description of the countries clearly reveals in him a specialist-strategist: it is not the beauty of the described places that seduces him, but their importance as strategic points. In our tradition, Arrian opens this kind of work with a description of the Black Sea coast. An accurate knowledge of the area was essential for Roman expansion. This "Description" falls into three parts. The first part he addresses to the Emperor Hadrian; it tells the story of Arrian's visit to the Black Sea, before being received by him in 131 on behalf of the emperor. The second part is stingy with descriptions, it only talks about the distances between points on the coast from the Thracian Bosporus to Trebizond. The third part contained a description of the journey from Sebastopolis (Dioscuriada) to Byzantium. All three parts served different purposes. If the first satisfied more general geographic interests, the other two pursued practical goals; they were navigational guides. In ancient times, the description of such routes was very common. They were used by sailing merchants who set off to unknown countries. They were of particular importance for naval campaigns, giving an idea of where garrisons should be deployed in the newly conquered countries.

Another work, once attributed to Arrian, has survived under the title Travels along the Coasts of the Red Sea. Apparently, the same title and the same plot forced them to be attributed to the same author. And the description of the Red Sea contains a thorough description of the port sea points. This is a very valuable work. It indicates everything that a merchant-sailor needs to know during a long "walk" in the Red Sea, along the shores of southern Arabia, India, etc. However, along with the information that was known to the author from his own observation, there are also fantastic reports, which, perhaps, he himself did not believe, but did not dare to throw away. This kind of literature found imitators at a much later time. However, philological science long ago abandoned the idea of considering Arrian the author of the description of the Red Sea: this is not allowed by both the stylistic manner alien to him, and the peculiarities of his language.

After completing his studies in philosophy with Epictetus, Arrian devotes himself entirely to serving the Roman state. An inscription accidentally discovered mentions Arrian among the imperial delegates in Greece under the command of Avidius Nigrin. This refers to 116, then, apparently, he was already a senator. The task of the commission was to determine the exact boundaries of the "sacred" land of the Delphic temple. The office work was carried out in Greek and Latin. This is a small illustration of how the emperors recruited officials from Greek cities for this kind of business. In the years 121–124, Emperor Hadrian conferred the rank of consul on Arrian. From 131 to 137, he, as the personal legate of the emperor, ruled the province of Cappadocia, a place of great responsibility. Cappadocia was then subjected to continuous attacks from the Alans, and the emperor Hadrian was forced to send there a person experienced in military affairs. Apparently, the choice was made well. This can be concluded from the very lively judgments about military issues included in Arrian's story about Alexander's campaign. Arrian received solid practical knowledge of military affairs while in the civil service, participating in campaigns. However, we have no data to clarify. By reasoning, we can still form a definite opinion about the knowledge of Arrian. Without his own experience, Arrian would not have been able to understand the sources he used when working on Alexander's Campaign. Remarks about the battle at Gaugamela and in other points, about the battle formations of Alexander's troops, the preference of some sources for others testify not only to Arrian's common sense, but also to his deep knowledge. From the characteristics of the geographical features of Istra, the Inn and Sava rivers, we can conclude that he once visited here. Arrian's remark about how the Romans built bridges is especially characteristic.

The researcher Arrian, analyzing the corresponding place in his work, involuntarily faces the question: did Arrian judge this or that problem only by the sources, or, borrowing reasoning from the source, adds his remarks, or, finally, illuminates the problem based on his own observations, as an eyewitness ...

Arrian's work admits only this latter interpretation. This is supported, firstly, by the fact that the remark about the methods of building bridges by Roman soldiers here interrupts the story of Alexander's progress. The impetus for this logical retreat was given by thinking about that. how Alexander threw a bridge over the Indus River. Arrian knows two kinds of bridges: permanent bridges and temporary bridges. He believes that Alexander was unlikely to build the bridge in the same way as bridges were built at Darius across the Danube or at Kssrkss across the Hellespont. Arrian writes: “... or the bridge was built in the way that, if necessary, the Romans use on Istria, on the Celtic Rhine, on the Euphrates and the Tigris. The fastest way to build bridges among the Romans, I know, is to build a bridge on ships; I’ll talk about how it’s done now, because it’s worth mentioning. ” In the first part of the above passage, Arrian used the testimony of Herodotus, and the story of Roman bridge building is presented in such a way that one has to consider it a memory from his own practice. The final phrases are especially interesting: “Everything ends very quickly, and, despite the noise and rumbling, the order in the work is observed. It happens that from every ship there are encouraging cries and abuse pours down on those who lag behind, but this does not interfere with either following orders or working with great speed. " This description seems to show us the warlord Arrian, surrounded by working sappers, who encourages them by shouting or scolding. He could not read this detail in any source. It is felt that the old officer recalls with some excitement a case from his practice of hurriedly building bridges, i.e. crossings across the Rhine and Istres, the Euphrates and the Tigris during hostilities. These considerations of ours lead us to assume that at some stage of his life he participated in the indicated places in hostilities. Such campaigns could have taken place during the reign of Hadrian (117–138), when the Romans waged a desperate struggle to preserve the integrity of the empire against the Dacians, Celts and in the east. We know that Arrian was well informed, not only theoretically, from his work on the tactics he wrote, apparently in connection with the governorship in Cappadocia. Questions of tactics were discussed even under Trajan. In 136, the emperor Hadrian commissioned Arrian to compose a new work on this issue. Apparently, Adrian wanted such a book to have the character of a textbook for the training of military leaders and to take into account the new tactical views of Adrian himself. This guide is divided into two sections. In the first, Arrian outlined the tactics of the previous period, that is, the Greeks and Macedonians, and the second part explained the meaning and significance of Hadrian's reforms in the field of cavalry tactics. For the first part, Arrian had to use special literature, and in the second part he explains the special terminology. The "History of the Alans", which undoubtedly also arose during the rule of Cappadocia, belongs to the same range of questions. From this book survived a passage "Formation against the Alans", which outlines the difference between Greek and Roman tactics.

From the end of the reign of Hadrian, Arrian is removed from participation in Roman state and military life. The reasons for this are unknown to us. But the termination of state and military service in Rome does not mean a complete retirement from business for Arrian: from now on, he, perhaps, more intensively and more than before, devotes himself to literary activity, and he occupies only local positions. In 147, Arrian was elected as an eponymous archon in Athens and awarded civil rights in the demos of Payania.

This post had no great political significance: the archon-eponym headed only the college of archons, and the year was named after him - for a narrow circle of Athens. Of course, Arrian could only hold this position with the consent of the Roman emperor. Further, it is also testified that Arrian in Nicomedia was chosen as a priest of the goddesses of the underworld of Demeter and Persephone. No further information on his life path is found.

Arrian's book "On the Hunt" is closely related to Xenophon. It was written in Athens, when Arrian was under the spell of this writer. In this work, he supplements Xenophon's information with information from the hunting practice of the Celts.

We have to regret that the biographies of Timoleon and Dion, who interested Arrian as strategists, did not reach us. They would help us, perhaps, to understand more clearly what the peculiarities of Arrian the biographer are. In the II century. n. e. this literary genre has already been developed and represented by a number of major writers, of whom Plutarch is the most famous. What, according to Arrian, was included in the concept of biography, you need to know when studying his "Campaign of Alexander", conceived to a large extent as a biographical work.

Arrian also belongs, probably, to the lost biography of the robber Tillobor. Literary interest in the biographies of "noble robbers" arises even in pre-Hellenistic times. Theopompus talked about the just robber or prince Bardulis. Cicero, in his treatise on duties, on the basis of the relevant literature, speaks of the organization of the relationship between the robbers. We know little about the reason for the emergence of this topic. The Stoics showed by the examples of these "despicable" people that a person is born with a desire for some order, a desire for ethical standards. Perhaps the Stoic Arrian was interested in their social life precisely from this point of view.

Description of Alexander's campaign

The central place in the work of Arrian is undoubtedly his "Campaign of Alexander". This remarkable work is the best exposition of the work of Alexander, which was written in antiquity. From a purely external point of view, we can establish that Arrian writes under the influence of Xenophon. Just as Xenophon in his "Campaign 10,000" tells about the campaign of Cyrus the Younger, Arrian illuminates the campaign of Alexander step by step. This work is divided into seven books - also in imitation of Xenophon. Before Arrian, many works about Alexander appeared. But their authors did not try to communicate the truth about the deeds and days of their hero. Alexander did not find himself a historian who could tell about him "in a dignified manner." If Arrian asserts that about Alexander “is not written either in prose or in verse,” then this, of course, does not correspond to the truth. Indeed, at the beginning of the book about the "Campaign" he asserts that "there is no person at all about whom they write more and more contradictory." Arrian even promises to mention "the stories that circulate about Alexander" as necessary. This is done throughout the book. Arrian ends his assessment of the literature about Alexander in the introduction with the words: “If anyone wonders why it occurred to me to write about Alexander, when so many people wrote about him, then let him first read all their writings, get to know mine - and then let him be surprised ". So the point, of course, is not the absence of literature about Alexander, but the fact that from the point of view of Arrian as a qualified military leader, all these writings are not able to give an adequate idea of

Alexandra. And therefore, they know much more about the commanders, who cannot be compared with Alexander. Alexander did not find such a writer as Cyrus found in the person of Kssnophon. Arrian wanted to be such a writer for Alexander. That Alexander, as a commander, stood immeasurably higher than Cyrus, was for Arrian undoubtedly. “This is what prompted me to write about him; I don’t think I’m not worthy to take on the task of illuminating the deeds of Alexander to people. Therefore, I say, I took up this essay. Who I am, I myself know and do not need to give my name (it is not unknown to people as it is), to name my fatherland and family and talk about what position I was invested in in my homeland. Let me tell you this: these occupations have become my fatherland, family, and position, and this has been so since my youth. Therefore, I believe that I deserve a place among the first Hellenic writers, if Alexander is the first among the warriors. " The thought involuntarily suggests itself that Arrian's plan to describe Alexander's campaign matured in his youth, and it is very likely that not only himself, but also his friends and foes, such an undertaking seemed inconsistent with the forces and position of Arrian, especially since books already existed on this topic. Only many years later, having gained knowledge in the military field and related sciences, having accumulated a lot of life experience, was he able to implement this plan - to become Xenophon for Alexander. Proceeding from this, it seems that the "Campaign" was written by a mature connoisseur, as recommended by both the story itself and his judgments. The "campaign" was written, obviously, at the end or rather after the end of Arrian's active military activities, that is, after the death of Emperor Hadrian. It would be interesting to know what biographical literature about Alexander existed before Arrian, about which he speaks so disapprovingly at the beginning of the book.

We know that Plutarch was interested in the life of Alexander. Excerpts on papyri by unknown authors have come down to us. We know the name of Soterich, who, under the emperor Diocletian, wrote the epic about the capture of Thebes by Alexander the Great. Even in pre-Roman times, the "novel about Alexander" was being composed, which was especially popular in the first three centuries of the Roman Empire. In the II century. n. e. A favorite topic for rhetorical exercises is the fictional correspondence between Darius and Alexander. Such letters have also been found in recent years on papyrus in the sands of Egypt. Compared to Arrian's conscientious work, their historical significance is negligible. The moralizing treatises were especially interested in the moral assessment of Alexander and (page with the picture - Smolyanin) the question of whether Alexander owes his successes to his own merits or "happiness." The time of Emperor Trajan especially encouraged interest in Alexander and the assessment of his activities, since Trajan willingly compared himself with Alexander and favored those who made this comparison. Of course, such a hobby favored the appearance of works about Alexander and could indirectly contribute to the appearance of Arrian's "Campaign of Alexander". The question arose: who is higher as a commander - Alexander or the Roman generals? We learn about this problem from the work of the sophist-orator Aelius Aristides (117-189 CE). He, of course, answered very evasively: Alexander, they say, is the largest commander, but he did not know how to manage the conquered territories. With this answer, he did not humiliate the Macedonian commander, and managed to please the Romans. But it is not the formulation of the question and its solution by Elius Aristides that is important: it is interesting under what conditions Alexander the Great was recognized by the official Rome as a genius commander. Alexander's praise alone could not satisfy Arrian. In his work, with all the positive attitude towards his hero, he tries to recognize the negative features of his behavior.

Arrian's description of India occupies a special place in his "Alexander's Campaign". He was very interested in this country. This was common to all Greeks; India for them was then an unknown country, only fragmentary and contradictory stories, embellished with myth-making, reached about it. Storytellers associated the feats of the ancient gods with this country. In his "Campaign of Alexander" Arrian formulates the questions to which his readers could expect an answer from him: neither about the outlandish animals that live in this country, nor about the fish and monsters that are found in the Indus, Hydaspe, Ganges and other Indian rivers; I do not write about the ants that mine gold, or about the vultures that guard it. All these are stories, created more for entertainment than for the purpose of a truthful description of reality, as well as other ridiculous fables about the Indians, which no one will neither investigate nor refute. " He pays tribute to the discoveries of Alexander and his associates in the field of the life of the Indians, the geography of the region, etc. But he refuses the idea of describing India in more detail than the framework of the story about the "Campaign" allows.

“About the Indians, however, I will write separately: I will collect the authentic in the stories of those who fought with Alexander: Nearchus, who traveled around the Great Indian Seafood, in the writings of two famous men, Eratosthenes and Megasthenes, and I will tell you about the customs of the Indians, about the outlandish animals that are found there, and the journey itself along the Outer Sea. " He refuses to report anything about their teachings in the appropriate place (concerning the movement of the brahmanas). He only says that these are Indian sages. “In a book about India,” he says, “I’ll talk about their wisdom (if they have a net at all).” And Arrian actually wrote a book about India. The source of the book was information provided by Nearchus, the commander of Alexander's fleet. After completing the task of Alexander (that is, sailing from the Indus on the Outer Sea), Nearchus reported in detail to the Macedonian king. “About the voyage of Nearchus from the Indus to the Persian Sea and to the mouths of the Tigris,” says Arriai, “I will write separately, following Nearchus's own work — there is this Greek book about Alexander. I will do it later, if desires and God direct me to this. " Only in one part did Arrian fail to fulfill his promise: he did not write about the teachings of the brahmanas. Attempts already by ancient writers (for example, Strabo) to challenge the authenticity of Nearchus's work on India are untenable. Strabo's distrust is based on the fact that some of the details of India's description could not be explained by the science of modern Strabo. The current knowledge of geography confirms much that at one time seemed incredible.

The rest of Arrian's writings have not survived. This is especially regrettable, since they talked about times that are poorly reflected in other sources. So, in particular, from 10 books of the history of the time after Alexander the Great, pitiful remnants have come down to us. But these 10 books were a very detailed exposition of only a two-year history of the Diadochi, that is, the Hellenistic rulers after the death of the Macedonian conqueror. The loss of the work "History of Bithynia" (in 8 books), ie, the country where the writer was born, is especially annoying, because in this work Arrian probably collected very interesting and reliable information. True, this work embraced only the initial period of the history of Bithynia - up to 75 BC. e., when the country was ruled by king Nicomedes III. Arrian also wrote The History of the Parthians, which consisted of 17 books. Her particular interest was that it was brought before Trajan's Parthian War (113–117), of which Arrian was a contemporary. We know nothing about the time when these works were written; we also know very little about their nature. Papyrus finds bring from time to time information about the era of the Diadochi, but it is not possible to establish how these fragments relate to the works of Arrian.

Arrian's sources

One of the main questions for researchers of Arrian's work about the campaign of Alexander the Great is the problem of its sources, or otherwise - about the reliability of the historical material that makes up the backbone of the narrative. It is also important how Arrian was able to use his sources.

Even under Father Alexander. Philippe, there was a brilliantly organized chancellery at the Macedonian court. Alexander inherited this institution and turned it partly into his field office. In connection with the large scale of Alexander's activities, the duties of the chancellery also increased, the importance of that aspect of its activities, which was associated with the preparation and conduct of wars, increased. This is evidenced by the fact that Eumenes of Cardia stood at the head of the office, a man who, during the campaign, was involved as the leader of the cavalry. The chancellery retained its military character under Alexander until the end of his days. Eumenes was given the title of "supreme secretary". All state correspondence passed through his hands: letters from the tsar, orders, legalizations, etc. The office kept plans for military operations and reports on them, everyday records, in the preparation and preservation of which Alexander was very interested. Thanks to this, the dates of the battle and descriptions of the course of military events have been preserved. We can get an idea of the organization of the chanceries, so to speak, the clerical style of Macedonia from the numerous documents that have come down to us from the offices of senior officials of Ptolemaic Egypt - I mean the so-called "Zeno's archive". Zeno was the right hand of Apollonius, the closest associate of Ptolsmey II Philadelphus, the chief ruler of the economic life of Egypt. The obliging Zeno, with exceptional consistency, made sure that each document from the correspondence contained the following information. When the document arrived, it was written on the back of it: who is the sender, to whom the letter is addressed, what is the content of the letter, where it was received, the date of receipt, i.e. year, month, day, sometimes hour. This made it possible to draw up, if necessary, summaries of letters, reports, etc. Since in important cases the time of departure was indicated in the letter itself, this entry on the back of the letter served as a supporting document in case of a question about the timeliness of delivery (page with a picture. - Smolyanin) letters and the timeliness of the execution of orders. The letter of Apollonius to Zeno is indicative in this respect. It contained an order to send transport animals to meet the envoys of the Bosporus king Pairisad II. The letter is dated (translated into the modern calendar) 254 BC. B.C., September 21. On the back with the other hand, that is, the hand of Zeno's secretary, it is written that the letter was received the same year on September 22 at 1 o'clock and concerns the sending of transport animals for the ambassadors of Payrisad and the ambassadors of the city of Argos. It seems that such a clear style of document registration has been practiced for a long time.