What does theoretical argument mean? theoretical reasoning. What is argumentation

General statements, scientific laws, principles, etc. cannot be substantiated purely empirically, by reference only to experience. They also require a theoretical justification based on reasoning and referring to other accepted statements. Without this, there is neither abstract theoretical knowledge nor well-founded beliefs.

It is not possible to prove a general statement by referring to evidence relating to any particular instance of its applicability. Universal generalizations of science are a kind of hypotheses built on the basis of essentially incomplete series of observations. Such universal statements cannot be proved not only on the basis of the observations in the course of generalization of which they were put forward, but also on the basis of the subsequent extensive and detailed series of predictions derived from them and found their confirmation in experience.

Theories, concepts and other generalizations of empirical material are not logically deduced from this material. The same set of facts can be generalized in different ways and covered by different theories. However, none of them will be fully consistent with all the facts known in their field. The facts and theories themselves not only constantly diverge from each other, but they are never clearly separated from each other.

All this suggests that the agreement of the theory with experiments, facts or observations is not enough for an unambiguous assessment of its acceptability. Empirical argumentation always requires the addition of a theoretical one. Not empirical experience, but theoretical reasoning is usually decisive when choosing one of the competing concepts.

Unlike empirical argumentation, the methods of theoretical argumentation are extremely diverse and internally heterogeneous. They include deductive reasoning, systemic reasoning, methodological reasoning, etc. There is no single, consistent classification of methods of theoretical argumentation.

1. Deductive justification

One of the important ways of theoretical argumentation is deductive argumentation.

An argument in which some statement follows (logically follows) from other statements is called deductive, or simply deduction.

Deductive reasoning is the derivation of a substantiated position from other, previously accepted statements.

If the advanced position can be logically (deductively) deduced from already established provisions, this means that it is acceptable to the same extent as these provisions themselves.

Suppose someone who is not familiar with the basics of the theory of electricity, conjectures that direct current is characterized not only by strength, but also by voltage. To confirm this conjecture, it is enough to open any reference book and find out that every current has a certain voltage. From this general position it follows that direct current also has voltage.

In the story of Leo Tolstoy (The Death of Ivan Ilyich) there is an episode that is directly related to logic.

Ivan Ilyich felt that he was dying and was in constant despair. In an agonizing search for some kind of light, he even seized on his old idea that the rules of logic, which are always true for everyone, are inapplicable to him. “That example of the syllogism that he studied in Kizevetter’s logic: Kai is a man, people are mortal, therefore Kai is mortal, seemed to him throughout his life to be correct only in relation to Kai, but not in any way to him. It was Kai - a man, a man in general, and it was absolutely fair; but he was not Kai and not a man in general, but he was a very, very special being from all the others ... And Kai is definitely mortal, and it’s right for him to die, but not for me, Vanya, Ivan Ilyich, with all my feelings, thoughts, - It's a different matter for me. And it can't be that I should die. It would be too terrible."

The course of Ivan Ilyich's thoughts is dictated, of course, by the despair that gripped him. Only it can make one assume that what is true always and for everyone will suddenly turn out to be inapplicable at a particular moment to a particular person. In a mind not terrified, such an assumption cannot even arise. However undesirable the consequences of our reasoning may be, they must be accepted if the premises are accepted.

Deductive reasoning is always, in some sense, coercion. When we think, we constantly feel pressure and unfreedom. It is no coincidence that Aristotle, who was the first to emphasize the unconditional nature of logical laws, noted with regret:

“Thinking is suffering,” for “if a thing is necessary, it is a burden to us.”

In normal reasoning processes, fragments of deductive reasoning usually appear in a very abbreviated form. Often the result of deduction looks like an observation rather than the result of a reasoning.

Good examples of deductions, in which the conclusion appears as an observation, are given by A. Conan Doyle in stories about Sherlock Holmes.

“Dr. Watson, Mr. Sherlock Holmes,” Stamford introduced us to each other.

Hello! Holmes said kindly. - I see you lived in Afghanistan.

How did you guess? I wondered...

Due to a long habit, the chain of inferences arises in me so quickly that I came to a conclusion without even noticing the intermediate premises. However, they were, these parcels. The course of my thoughts was as follows: “This person is a doctor by type, but he has a military bearing. So, a military doctor. He has just arrived from the tropics - his face is swarthy, but this is not the natural shade of his skin, since his wrists are much whiter. The face is emaciated, - obviously, he has suffered a lot and endured the disease. He was wounded in his left hand - he holds it motionless and a little unnaturally. Where, under the tropics, could an English military doctor suffer hardships and get a wound? Of course, in Afghanistan” 58 .

Justifying the statement by deriving it from other accepted provisions, we do not make this statement absolutely reliable and irrefutable. But we fully transfer to it the degree of certainty that is inherent in the propositions accepted as premises of deduction. If, say, we are convinced that all people are mortal and that Ivan Ilyich, with all his particularity and uniqueness, is a man, we are obliged to admit that he is also mortal.

It may seem that deductive justification is, so to speak, the best of all possible methods of justification, since it gives the justified assertion the same firmness as the premises from which it is deduced. However, such an estimate would be clearly overstated. It is far from always possible to derive new general propositions from established truths. The most interesting and important statements that can be premises of justification, as a rule, are themselves general and cannot be consequences of existing truths. Statements requiring substantiation usually speak of relatively new, not studied in detail phenomena that are not yet covered by universal principles.

Justifying some statements by referring to the truth or acceptability of other statements is not the only function performed by deduction in the processes of argumentation. Deductive reasoning also serves to verify (indirectly confirm) statements: from the verified position, its empirical consequences are deductively derived; confirmation of these consequences is evaluated as a possible argument in favor of the original position. Deductive reasoning can also be used to falsify hypotheses. In this case, it is demonstrated that the consequences arising from the hypotheses are false. Unsuccessful falsification of data is a weakened version of verification: failure to disprove the empirical consequences of the hypothesis being tested is an argument, albeit a very weak one, in support of this hypothesis. And finally, deduction is used to systematize a theory, trace the logical connections of its constituent statements, build explanations based on the general principles offered by the theory. The clarification of the logical structure of the theory, the strengthening of its empirical base and the identification of its general premises is, as will be clear from what follows, a contribution to the substantiation of the statements included in it.

Deductive reasoning is applicable in all areas of reasoning and in any audience.

Here is an example of such an argument, taken from the theological literature: “I want to prove here,” writes C.S. life, but I refuse to believe that He was God.” That's what you shouldn't say. What great teacher of life, being just a man, would say what Christ said? In that case, he would either be crazy - no better than a sick man pretending to be a boiled egg - or a real devil. There is no escape from the choice. Either this man was and remains the Son of God, or he was insane, or even worse ... You can not listen to Him, considering Him foolish, you can spit on Him and kill Him, considering Him the devil, or you can fall at His feet, calling Him Lord God. Let's not just carry any patronizing nonsense About the teachers of life. He didn’t leave us such a choice, and He didn’t want to leave us” 59 . This argument is typically deductive, although its structure is not particularly clear.

More simple and clear is the reasoning of the medieval philosopher I.S. Eriugena: “And if bliss is nothing but eternal life, and eternal life is the knowledge of the truth, then bliss is nothing but the knowledge of the truth” 60 . This reasoning is a deductive inference, namely a categorical syllogism (the first figure, mode Barbara).

The share of deductive reasoning in different fields of knowledge is significantly different. It is used very widely in mathematics and mathematical physics, and only occasionally in history or philosophy. Aristotle wrote, having in mind just the scope of application of deductive reasoning: "Scientific evidence should not be required from the speaker, just as emotional conviction should not be required from mathematics" 61 . A similar thought was expressed by F. Bacon: "...Excessive pedantry and cruelty, requiring too strict proofs, and even more negligence and readiness to be satisfied with very superficial proofs in others, brought great harm to science and greatly retarded its development" 62 . Deductive reasoning is a very powerful tool, but like any such tool, it must be used narrowly.

Depending on how widely deductive reasoning is used, all sciences are usually divided into deductive and inductive. In the former, deductive reasoning is predominantly or even exclusively used. Secondly, such argumentation plays only a deliberately auxiliary role, and in the first place is empirical argumentation, which has an inductive, probabilistic character. Mathematics is considered a typical deductive science, and the natural sciences are an example of inductive sciences.

The division of sciences into deductive and inductive, which was widespread several decades ago, has now largely lost its former significance. It is focused on science, considered in statics, primarily as a system of reliably established truths.

Applying the rules of deduction to any premises guarantees conclusions that are as reliable as the premises themselves. If the premises are true, then the conclusions deduced from them are also true.

On this basis, the ancient mathematicians, and after them the ancient philosophers, insisted on the exclusive use of deductive reasoning.

Medieval philosophers and theologians also overestimated the importance of deductive reasoning. They were interested in the most general truths concerning God, man and the world. But in order to convince someone that God is essentially good, that man is his likeness, and that the divine order reigns in the world, deductive reasoning, starting from a few general principles, is much more suitable than induction and empirical argument. It is characteristic that all the proposed proofs of the existence of God were conceived by their authors as deductions from self-evident premises.

Here is how, for example, Thomas Aquinas sounded the "argument of a motionless engine." Things are divided into two groups - some are only moved, others move and at the same time move. Everything that is moved is set in motion by something, and since an infinite inference from effect to cause is impossible, at some point we must arrive at something that moves without being itself moved. This motionless engine is God. Thomas Aquinas gave four more proofs of the existence of God, which were again clearly deductive in nature: the proof of the first cause, which again rests on the impossibility of an endless inference from effect to cause; proof that there must be a finite source of all necessity; the proof that we find various degrees of perfection in the world, which must have their source in something absolutely perfect; proof that we find that even lifeless things serve a purpose which must be a purpose set by some being outside of them, that only living beings can have an inner purpose 63 . The logical structure of all these proofs is very obscure. And yet, at the time, they seemed extremely convincing.

In the early modern period, Dakart argued that mathematics, and geometry in particular, is a model for how science works. He believed that the fundamental scientific method is the deductive method of geometry, and imagined this method as a rigorous reasoning based on self-evident axioms. He thought that the subject of all physical sciences should be in principle the same as the subject of geometry, and that from the point of view of science, the only important characteristics of things in the physical world are the spatial characteristics studied by geometry. Descartes proposed a picture of the world in which the only realities besides God are, on the one hand, a purely mathematical substance that has no characteristics other than spatial ones, and, on the other hand, purely mental substances, the existence of which essentially consists in thinking, and in in particular in their ability to grasp self-evident axioms and their deductive consequences. There are, therefore, on the one hand, the object of geometry, and, on the other hand, souls capable of mathematical or geometric reasoning. Cognition is only the result of the application of this ability.

Deductive reasoning was overestimated as long as the study of the world was speculative and alien to experience, observation and experiment.

The concept of deduction is a general methodological one. In logic, it corresponds to the concept of proof.

A proof is usually defined as a procedure for substantiating the truth of a statement by citing those true statements from which it logically follows.

This definition includes two central concepts of logic: truth and logical consequence. Both of these concepts are not sufficiently clear, which means that the concept of proof defined through them cannot be classified as clear either.

Many of our statements are neither true nor false, they lie outside the "category of truth." These include requirements, warnings, etc. They indicate what the given situation should become, in which direction it should be transformed. We have the right to demand from descriptions that they are true. But a good order, advice, etc. we characterize as effective or expedient, but not as true.

The standard definition of proof uses the notion of truth. To prove a thesis means to logically deduce it from other, which are true positions. But, as we see, there are statements that are not connected with the truth. It is also obvious that, in dealing with them, one must be both logical and conclusive.

Thus, the question arises of a significant expansion of the concept of proof. It should cover not only descriptions, but also statements such as estimates and norms.

The problem of redefining the proof has not yet been solved either by the logic of estimates or by the logic of norms. As a result, the concept of proof remains not entirely clear in its meaning 64 .

This concept is defined through the law of logic: statement (or system of statements) A logically implies statement B if and only if the expression "if A, then B" is a law of logic.

This definition is only a general outline of an infinite number of possible definitions. Specific definitions of logical consequence are obtained from it by indicating the logical system that defines the concept of a logical law. There are, in principle, an infinite number of logical systems claiming the status of a law of logic. Well-known, in particular, are the classical definition of logical consequence, its intuitionistic definition, the definition of consequence in relevant logic, etc. However, none of the definitions of logical law and logical consequence available in modern logic is free from criticism and from what can be called “paradox logical following".

In particular, classical logic says that anything logically follows from a contradiction. For example, from the contradictory statement "Tokyo is a big city, and Tokyo is not a big city" follow, along with any others, the statements: "Mathematical set theory is consistent", "The moon is made of green cheese", etc. But there is no substantive connection between the original statement and these statements supposedly arising from it. This is a clear departure from the usual, or intuitive, notion of following. The situation is exactly the same with the classical proposition that logical laws follow from any statements. Our logical experience refuses to admit that, say, the statement "Ice is cold or ice is not cold" can be deduced from statements like "Two are less than three" or "Aristotle was the teacher of Alexander the Great." The consequence that is deduced must be somehow connected in its content with that from which it is deduced. Classical logic neglects this obvious circumstance.

These paradoxes concerning logical consequence also take place in intuitionistic logic. But in the latter, the law of the excluded middle, which is indisputable for classical logic, does not operate. A number of other logical laws are also discarded, which make it possible to prove the existence of objects that cannot be built or calculated. Among those rejected are, in particular, the law of removal of double negation and the law of reduction to absurdity, which gives the right to assert that a mathematical object exists if the assumption of its non-existence leads to a contradiction. This means that a proof carried out using classical logic will not necessarily be considered a proof from the point of view of intuitionistic logic as well.

More perfect than the classical and intuitionistic description of logical consequence has been given by relevant logic. She succeeded, in particular, in eliminating the standard paradoxes of logical consequence. Many other theories of logical consequence have also been proposed. Each of them has its own understanding of evidence.

The model of proof, which in one way or another tends to be followed in all sciences, is mathematical proof. “There is no real evidence anywhere,” wrote B. Pascal, “except in the science of geometers and where it is imitated” 65 . By "geometry" Pascal meant, as was common in his day, all of mathematics.

For a long time it was believed that mathematical proof is a clear and undeniable process. In our century, the attitude towards mathematical proof has changed. Mathematicians are divided into groups, each of which adheres to its own version of the proof. This was due to several factors. First of all, ideas about the logical principles underlying the proof have changed. Confidence in their uniqueness and infallibility has disappeared. There was also disagreement about how far the realm of logic extended. Logicists were convinced that logic was sufficient to justify all of mathematics; according to the formalists, logic alone is not enough for this, and logical axioms must be supplemented with purely mathematical ones; representatives of the set-theoretic direction were not particularly interested in logical principles and did not always indicate them explicitly; Intuitionists, for reasons of principle, considered it necessary not to go into logic at all. Summing up this revision of the concept of proof in mathematics, R. L. Wilder writes that mathematical proof is nothing more than “testing the products of our intuition ... It is quite clear that we have not possessed and, apparently, we never will possess a criterion of proof independent of time, of what is to be proved, or of those who use the criterion, be it an individual or a school of thought. Under these conditions, it is perhaps most reasonable to admit that, as a rule, there is no absolutely true proof in mathematics, although the general public is convinced of the opposite.

Mathematical proof is the paradigm of proof in general, but even in mathematics it is not absolute and final. “New counterexamples undermine old proofs, depriving them of their strength. The evidence is revised and the new versions are erroneously considered definitive. But, as history teaches, this only means that the time has not yet come for a critical review of the proof.

The mathematician does not rely on rigorous proof to the extent that is commonly believed. “Intuition can be more satisfactory and inspire more confidence than logic,” writes M. Kline. - When a mathematician asks himself why a given result is true, he seeks an answer in an intuitive way. Having discovered a misunderstanding, the mathematician subjects the proof to the most thorough critical revision. If the proof seems right to him, he will do his best to understand why his intuition failed him. The mathematician longs to understand the inner reason why a chain of syllogisms works successfully... The progress of mathematics has undoubtedly been mainly promoted by people endowed not so much with the ability to carry out rigorous proofs as with an unusually strong intuition” 68 .

Thus, even a mathematical proof does not have absolute persuasiveness and guarantees only relative certainty in the correctness of the proven position. As K. Aidukevich writes, “to say that in the deductive sciences such statements are considered justified for which a deductive proof is given, it means little to say, since we do not clearly know what constitutes that deductive proof, which makes the acceptance of the proved legitimate in the eyes of a mathematician. assertion or which constitutes its justification” 69 .

The overestimation of the role of evidence in argumentation is connected with the implicit assumption that a rational discussion should be in the nature of evidence, justification, or logical derivation from some initial principles. These principles themselves must be taken on faith if we are to avoid endless peipecca, references to more and more principles. However, real discussions only in rare cases take the form of deducing the provisions under discussion from some more general truths.

Catalog: book -> philosophy

philosophy -> Meaning of life and acme: 10 years of searching Proceedings of VIII x symposia Ed. A. A. Bodaleva, G. A. Vaiser, N. A. Karpova, V. E. Chukovsky Part 1 Moscow Smysl 2004

Logical culture, which is an important part of the general human culture, includes many components. But the most important of them, connecting, as in an optical focus, all other components, is the ability to reason argumentation.

Argumentation is the presentation of arguments, or arguments, with the intent to arouse or increase the support of the other side (audience) for the proposition put forward. "Argumentation" is also called the totality of such arguments.

The purpose of the argumentation is the acceptance by the audience of the provisions put forward. Truth and goodness can be intermediate goals of argumentation, but its ultimate goal is always to convince the audience of the justice of the position offered to its attention and, possibly, the action suggested by it. This means that the oppositions "truth-false" and "good-evil" are not central either in the argument or, respectively, in its theory. Arguments can be given not only in support of theses that seem true, but also in support of deliberately false or vague theses. Argumentation can be defended not only by goodness and justice, but also by what seems or later turns out to be evil. The theory of argumentation, proceeding not from abstract philosophical ideas, but from real practice and ideas about a real audience, should, without discarding the concepts of truth and goodness, put the concepts of "belief" and "acceptance" at the center of its attention.

The argument distinguishes thesis- a statement (or a system of statements) that the arguing party considers it necessary to inspire the audience, and an argument, or argument, - one or more related statements intended to support the thesis.

Argumentation theory explores the diverse ways of persuading an audience with the help of speech influence. You can influence the beliefs of listeners or viewers not only with the help of speech and verbal arguments, but also in many other ways: gesture, facial expressions, visual images, etc. Even silence in certain cases turns out to be a strong enough argument. These methods of influence are studied by psychology, the theory of art, but are not affected by the theory of argumentation. Beliefs can be further influenced by violence, hypnosis, suggestion, subconscious stimulation, drugs, drugs, and the like. Psychology deals with these methods of influence, but they clearly go beyond the framework of even a widely interpreted theory of argumentation.

Argumentation is a speech action that includes a system of statements designed to justify or refute an opinion. It is addressed primarily to the mind of a person who is able, by reasoning, to accept or refute this opinion. The argument is thus characterized by the following features: it is always expressed in language, takes the form of spoken or written statements, argumentation theory explores the relationships of these statements, and not the thoughts, ideas and motives behind them; is purposeful activity, whose task is to strengthen or weaken someone's beliefs; This social activity, since it is directed at another person or other people, involves dialogue and an active reaction of the other side to the arguments; argumentation suggests reasonableness those who perceive it, their ability to rationally weigh arguments, accept them or challenge them.

The theory of argumentation, which began to take shape in antiquity, has gone through a long history, rich in ups and downs. Now we can talk about the formation new argumentation theory, emerging at the intersection of logic, linguistics, psychology, philosophy, hermeneutics, rhetoric, eristics, etc. The actual task is to build a general theory of argumentation that answers such questions as: the nature of argumentation and its boundaries; ways of argumentation; originality of argumentation in different areas of knowledge and activity, starting with the natural and human sciences and ending with philosophy, ideology and propaganda; a change in the style of argumentation from one era to another due to a change in the culture of the era and its characteristic style of thinking, etc.

The central concepts of the general theory of argumentation are: persuasion, acceptance (statements or concepts), audience, method of argumentation, position of the participant in the argumentation, dissonance and consonance of positions, truth and value in argumentation, argumentation and proof, etc.

The general contours of a new theory of argumentation have been outlined in the last two or three decades. It restores the positive that was in ancient rhetoric and is sometimes called "new rhetoric" on this basis. It became obvious that the theory of argumentation is not reducible to the logical theory of proof, which is based on the concept of truth and for which the concepts of persuasion and audience are completely foreign. The theory of argumentation is also not reducible to the methodology of science or the theory of knowledge. Argumentation is a certain human activity that takes place in a specific social context and has as its ultimate goal not knowledge in itself, but the conviction of the acceptability of some provisions. The latter may include not only descriptions of reality, but also assessments, norms, advice, declarations, oaths, promises, etc. Argumentation theory is not limited to eristic- the theory of the dispute, because the dispute is only one of many possible situations of argumentation.

The works of H. Perelman, G. Johnston, F. van Yemeren, R. Grootendorst and others played an important role in the formation of the main ideas of the new theory of argumentation. hardly visible field of different opinions on the subject of this theory, its main problems and development prospects.

In the theory of argumentation, argumentation is considered from three different positions that complement each other: from the point of view of thinking, from the point of view of human And societies, and finally, in terms of stories. Each of these aspects of consideration has its own specific features and is divided into a number of subdivisions.

The analysis of argumentation as a human activity of a social nature involves the study audiences in which it unfolds. The narrowest audience includes only the one who puts forward a certain position or opinion, and the one whose beliefs he seeks to strengthen or change. A narrow audience can be, for example, two people arguing or a scientist putting forward a new concept, and the scientific community called to evaluate it. The wider audience in these cases will be all those who are present at the dispute, or all those who are involved in the discussion of a new scientific concept, including non-specialists recruited to one side through propaganda. The study of the social dimension of argumentation also involves an analysis of the dependence of the manner of argumentation on the general characteristics of that particular holistic society or community within which it takes place. A typical example is the features of argumentation in the so-called “collectivist (closed) societies” (totalitarian society, medieval feudal society, etc.) or “collectivist communities” (“normal science”, army, church, totalitarian political party, etc.). The study of the historical dimension of argumentation includes three time slices:

Accounting for that historically specific time in which the argumentation takes place and which leaves its fleeting mark on it.

The study of the style of thinking of the historical era and those features of its culture that leave their indelible imprint on any argument relating to this era. Such a study allows us to single out five fundamentally different, replacing each other types, or styles, of argumentation: archaic (or primitive) argumentation, ancient argumentation, medieval (or scholastic) argumentation, “classical” argumentation of the New Age and modern argumentation.

An analysis of the changes that argumentation undergoes throughout human history. It is in this context that it becomes possible to compare the styles of argumentation of different historical eras and raise questions about the comparability (or incomparability) of these styles, the possible superiority of some of them over others, and, finally, about the reality of historical progress in the field of argumentation.

The theory of argumentation interprets argumentation not only as a special technique for persuading and substantiating the propositions put forward, but also as a practical art that involves the ability to choose from a variety of possible methods of argumentation that combination and that of their configuration that are effective in a given audience and are due to the peculiarities of the problem under discussion.

2. Rationale

In the most general sense, to substantiate a statement means to give those convincing or sufficient grounds (arguments), by virtue of which it should be accepted.

The substantiation of theoretical propositions, as a rule, is a complex process that cannot be reduced to the construction of a separate conclusion or the conduct of a single-act empirical, experimental verification. Justification usually includes a whole series of procedures concerning not only the proposition under consideration, but also that system of statements, that theory, of which it is an integral element. An essential role in the justification mechanism is played by deductive reasoning, although only in rare cases can the process of justification be reduced to an inference or a chain of inferences.

The knowledge validity requirement is commonly referred to as principle of sufficient reason. This principle was first explicitly formulated by the German philosopher and mathematician G. Leibniz. “Everything that exists,” he wrote, “has sufficient grounds for its existence,” due to which not a single phenomenon can be considered real, not a single statement is true or just without indicating its basis.

All the diverse ways of substantiation, which ultimately provide sufficient grounds for accepting the statement, are divided into absolute And comparative. Absolute justification is the presentation of those convincing, or sufficient grounds, by virtue of which the justified position should be adopted. Comparative justification - a system of convincing arguments in support of the fact that it is better to accept a justified position than another position that is opposed to it. The set of arguments given in support of the justified position is called basis.

The general scheme, or structure, of absolute justification: " A must be taken into effect WITH", Where A- substantiated position and WITH- basis of justification. Comparative Rationale Structure: “It is better to take A, how B, due to C. For example, the expression “We must accept that the sky is blue under normal conditions, since direct observation speaks in favor of this” is an absolute justification, its summarizing part. The expression “It is better to accept that the sky is blue than to accept that it is red, based on the provisions of atmospheric physics” is the resulting stage of the comparative justification of the same statement “The sky is blue”. Comparative justification is sometimes also called rationalization: in conditions when absolute justification is unattainable, comparative justification is a significant step forward in improving knowledge, in bringing it closer to the standards of rationality. Clearly, comparative justification is not reducible to absolute justification: if it can be justified that one statement is more plausible than another, this result cannot be expressed in terms of the isolated validity of one or both of these statements.

The requirements of absolute and comparative validity of knowledge (its validity and rationality) play a leading role both in the system of theoretical and practical thinking, and in the field of argumentation. All other topics of epistemology intersect and concentrate in these requirements, and it can be said that validity and rationality are synonymous with the ability of the mind to comprehend reality and draw conclusions regarding practical activity. Without these requirements, argumentation loses one of its essential qualities: it ceases to appeal to the mind of those who perceive it, to their ability to rationally evaluate the arguments presented and, on the basis of such an assessment, accept or reject them.

The problem of absolute justification was central to modern epistemology. The specific forms of this problem have changed, but in the thinking of a given era they have always been associated with its characteristic idea of the existence of absolute, unshakable and unreviewed foundations of any genuine knowledge, with the idea of a gradual and consistent accumulation of “pure” knowledge, with the opposition of truth, which allows justification, and subjective values that change from person to person, with a dichotomy of empirical and theoretical knowledge and other "classical prejudices". It was about a method or procedure that would provide unconditionally solid, undeniable foundations for knowledge.

With the decomposition of "classical" thinking, the meaning of the problem of substantiation has changed significantly. Three things became clear:

There are no absolutely reliable and not revised over time grounds and theoretical and even more so practical knowledge, and we can only talk about their relative reliability;

In the process of substantiation, numerous and varied techniques are used, the proportion of which varies from case to case and which are not reducible to some limited, canonical set of them, representing what can be called the "scientific method" or more broadly the "rational method";

Justification itself has limited applicability, being primarily a procedure of science and related technology and not allowing automatic transfer of justification patterns that have developed in some areas (and, above all, in science) to any other areas.

In modern epistemology, the “classical” problem of justification has been transformed into the task of investigating that variety of ways to justify knowledge, devoid of clear boundaries, with the help of which an acceptable level of justification is achieved in this area - but never absolute. The search for "solid foundations" for individual scientific disciplines has ceased to be an independent task, isolated from the solution of specific problems that arise in the course of the development of these disciplines.

Substantiation and argumentation are related to each other as a goal and a means: the methods of substantiation in the aggregate constitute the core of all the diverse methods of argumentation, but do not exhaust the latter.

The argumentation uses not only correct methods, which include methods of justification, but also incorrect methods (lies or treachery), which have nothing to do with justification. In addition, the argumentation procedure, as a living, direct human activity, must take into account not only the thesis being defended or refuted, but also the context of the argumentation, and primarily its audience. Justification techniques (proof, reference to confirmed results, etc.), as a rule, are indifferent to the context of the argumentation, in particular, to the audience.

Argumentation techniques can be, and almost always are, richer and sharper than justification techniques. But all methods of argumentation that go beyond the scope of methods of justification are obviously less universal and, in most audiences, less convincing than methods of justification.

Depending on the nature of the basis, all methods of argumentation can be divided into generally valid (universal) and contextual.

Valid argumentation applicable to any audience; efficiency contextual reasoning limited to certain audiences.

Commonly valid methods of argumentation include direct and indirect (inductive) confirmation; deduction of the thesis from the accepted general provisions; checking the thesis for compatibility with other adopted laws and principles, etc. Contextual ways of argumentation include reference to intuition, faith, authorities, tradition, and so on.

Obviously, not always contextual methods of argumentation are also methods of justification: for example, a reference to beliefs shared by a narrow friend of people, or to authorities recognized by this circle, is one of the common methods of argumentation, but definitely does not apply to methods of justification.

3. Empirical reasoning

All the various ways of substantiation (argument), which ultimately provide “sufficient grounds” for accepting a statement, can be divided into empirical And theoretical. The former rely primarily on experience, the latter on reasoning. The difference between them is, of course, relative, just as the very boundary between empirical and theoretical knowledge is relative.

Empirical methods of justification are also called confirmation, or verification(from lat. verus - true and facere - to do). Validation can be divided into direct And indirect.

Direct confirmation is the direct observation of those phenomena that are referred to in the test statement.

Indirect confirmation - confirmation in the experience of the logical consequences of the justified position.

A good example of direct confirmation is the proof of the hypothesis of the existence of the planet Neptune: soon after the hypothesis was put forward, this planet was seen through a telescope.

Based on the study of disturbances in the orbit of Uranus, the French astronomer J. Le Verrier theoretically predicted the existence of Neptune and indicated where telescopes should be directed in order to see a new planet. When Le Verrier himself was offered to look through a telescope at the planet found at the “tip of the pen”, he refused: “This does not interest me, I already know for sure that Neptune is exactly where it should be, judging by the calculations.”

It was, of course, unjustified self-confidence. No matter how accurate Le Verrier's calculations were, the assertion of the existence of Neptune remained until the observation of this planet, albeit highly probable, but only an assumption, and not a reliable fact. It could turn out that the perturbations in the orbit of Uranus are caused not by a yet unknown planet, but by some other factors. This is exactly what happened in the study of perturbations in the orbit of another planet - Mercury.

The sensory experience of a person - his sensations and perceptions - is a source of knowledge that connects him with the world. Justification by reference to experience gives confidence in the truth of such statements as "It's hot", "Twilight has come", "This chrysanthemum is yellow", etc.

It is not difficult, however, to notice that even in such simple statements there is no "pure" sensuous intuition. In a person, it is always permeated with thinking, without concepts and without an admixture of reasoning, he is not able to express even his simplest observations, to fix the most obvious facts.

We say, for example, "This house is blue" when we see the house in normal light and our senses are not disturbed. But we will say "This house looks blue" if there is little light or we doubt our ability to observe. To perception, to sensory "data", we add a certain idea of how objects are seen in ordinary conditions and what these objects are in other circumstances, in the case when our senses are able to deceive us. “Even our experience, obtained from experiments and observations,” writes the philosopher K. Popper, “does not consist of“ data ”. Rather, it consists of a web of conjectures—speculations, expectations, hypotheses, and so on—with which the traditional scientific and non-scientific knowledge and prejudices we have adopted are linked. There is simply no such thing as pure experience, obtained as a result of an experiment or observation.”

The "hardness" of sensory experience, of facts, is thus relative. It is not uncommon for facts that at first seem to be reliable, and in the course of their theoretical rethinking, have to be revised, clarified, or even completely discarded. The biologist K.A. Timiryazev drew attention to this. “Sometimes they say,” he wrote, “that a hypothesis must be in agreement with all known facts; it would be more correct to say - or to be able to detect the inconsistency of what is incorrectly recognized as facts and is in contradiction with it.

For example, it seems certain that if an opaque disk is placed between the screen and a point source of light, then a solid dark circle of shadow is formed on the screen, cast by this disk. In any case, at the beginning of the last century, this seemed an obvious fact. The French physicist O. Fresnel put forward a hypothesis that light is not a stream of particles, but the movement of waves. It followed from the hypothesis that there should be a small bright spot in the center of the shadow, since waves, unlike particles, are able to bend around the edges of the disk. There was a clear contradiction between hypothesis and fact. Subsequently, more carefully set up experiments showed that a bright spot does indeed form in the center of the shadow. As a result, it was not Fresnel's hypothesis that was discarded, but a fact that seemed obvious.

The situation is especially difficult with facts in the sciences of man and society. The problem is not only that some facts may turn out to be doubtful, or even simply untenable. It also lies in the fact that the full meaning of a fact and its specific meaning can only be understood in a certain theoretical context, when considering the fact from some general point of view. This particular dependence of the facts of the humanities on the theories within which they are established and interpreted was emphasized more than once by the philosopher A.F. Losev. In particular, he said that all so-called facts are always random, unexpected, fluid and unreliable, often incomprehensible; therefore, willy-nilly, one often has to deal not only with facts, but even more with those generalities, without which it is impossible to understand the facts themselves.

Direct confirmation is possible only in the case of statements about single objects or their limited collections. Theoretical propositions usually concern unlimited sets of things. The facts used in such confirmation are by no means always reliable and largely depend on general, theoretical considerations. There is nothing strange, therefore, that the scope of application of direct observation is rather narrow.

There is a widespread belief that in substantiating and refuting statements, the main and decisive role is played by facts, direct observation of the objects under study. This belief needs, however, substantial clarification. Bringing true and indisputable facts is a reliable and successful way of substantiating. Contrasting such facts with false or dubious propositions is a good method of refutation. An actual phenomenon, an event that is not consistent with the consequences of some universal proposition, refutes not only these consequences, but also the proposition itself. Facts, as you know, are stubborn things. When confirming statements relating to a limited range of objects, and refuting erroneous, divorced from reality, speculative constructions, the “stubbornness of facts” is manifested especially clearly.

And yet facts, even in their narrow application, do not have absolute "hardness." Even taken together, they do not constitute a completely reliable, unshakable foundation for the knowledge based on them. Facts mean a lot, but not everything.

As already mentioned, the most important and at the same time universal method of confirmation is indirect confirmation – derivation of logical consequences from the substantiated position and their subsequent experimental verification.

Here is an example of indirect confirmation that has already been used.

It is known that a strongly cooled object in a warm room is covered with dew drops. If we see that a person entering a house immediately fogs up his glasses, we can conclude with reasonable certainty that it is frosty outside.

The importance of empirically substantiating claims cannot be overemphasized. It is primarily due to the fact that the only source of our knowledge is experience - in the sense that knowledge begins with a living, sensual contemplation, with what is given in direct observation. Sensory experience connects a person with the world, theoretical knowledge is only a superstructure on an empirical basis.

However, the theoretical is not completely reducible to the empirical. Experience is not an absolute and indisputable guarantor of the irrefutability of knowledge. He, too, can be criticized, tested and revised. “In the empirical basis of objective science,” writes K. Popper, “there is nothing ‘absolute’. Science does not rest on a solid foundation of facts. The rigid structure of her theories rises, so to speak, above the swamp. It is like a building erected on stilts. These piles are driven into the swamp, but do not reach any natural or "given" foundation. If we stopped driving piles further, it was not at all because we had reached solid ground. We simply stop when we are satisfied that the piles are strong enough to support, at least for a while, the weight of our structure.”

Thus, if we limit the circle of ways of substantiating statements by their direct or indirect confirmation in experience, then it will turn out to be incomprehensible how it is still possible to move from hypotheses to theories, from assumptions to true knowledge.

4. Facts as examples and illustrations

Empirical data can be used in the course of argumentation as examples, illustrations And samples.

An example is a fact or special case used as a starting point for a subsequent generalization and to reinforce the generalization made.

“Next I say,” wrote the 18th century philosopher. J. Berkeley, - that sin or moral depravity does not consist in external physical action or movement, but in an internal deviation of the will from the laws of reason and religion. For killing an enemy in battle, or carrying out a death sentence on a criminal, is not considered sinful according to the law, although the external action here is the same as in the case of murder. Two examples are given here (murder in war and in the execution of a death sentence) to support the general proposition of sin or moral corruption. The use of facts or particular cases as examples must be distinguished from their use as illustrations or sample. Acting as an example, a particular case makes generalization possible; as an illustration, it reinforces an already established position; as a model, it encourages imitation.

An example can be used not only to support descriptive statements, but also as a starting point for descriptive generalizations. The example is incapable of supporting judgments and assertions, which, like norms, oaths, promises, recommendations, declarations, and the like, gravitate toward judgments. An example cannot serve as a starting material for evaluative and similar statements. What is sometimes presented as an example, designed to somehow support an assessment, a norm, etc., is in fact not an example, but a model. The difference between an example and a sample is significant: an example is a description, while a sample is an assessment related to some particular case and setting a particular standard, ideal, etc.

The purpose of the example is to lead to the formulation of the general proposition and, to some extent, to be an argument in support of the latter. Related to this is the selection criteria for the example. First of all, the fact or particular case chosen as an example should look clear and undeniable. It must also clearly enough express the tendency to generalization. With the requirement of tendentiousness, or typicality, of facts taken as an example, there is a recommendation to list several examples of the same type, if taken one by one they do not suggest with the necessary certainty the direction of the forthcoming generalization or do not reinforce the generalization already made. If the intention to argue with an example is not explicitly declared, the fact itself and its context should show that listeners are dealing with an example, and not with a description of an isolated phenomenon, perceived as simple information. The event used as an example should be taken, if not as usual, then at least as logically and physically possible. If this is not so, then the example simply breaks off the sequence of reasoning and leads just to the opposite result or comic effect. The example must be chosen and formed in such a way that it encourages a transition from the singular or particular to the general, and not from the particular again to the particular.

The opinion is sometimes expressed that an example should be given before the formulation of the generalization to which it pushes and which it supports. It is unlikely that this opinion is justified. The order of presentation is not particularly important for arguing by example. It may precede the generalization, but may also follow it. The function of an example is to push the thought towards a generalization and to support this generalization with a specific and typical example. If the emphasis is on giving thought movement and helping it to inertia come to a generalizing position, then the example usually precedes the generalization. If the reinforcing function of the example comes to the fore, then perhaps it is better to give it after generalization. However, these two tasks facing the example are so closely related that their separation and even more so their opposition, which affects the sequence of presentation, is possible only in abstraction. Rather, here we can talk about another rule related to the complexity and surprise of the generalization that is made on the basis of an example. If it is difficult or simply unexpected for the audience, it is better to prepare its introduction with an example that precedes it. If the generalization is known in general terms to the listeners and does not sound like a paradox to them, then an example can follow its introduction into the presentation.

An illustration is a fact or a special case, designed to strengthen the audience's conviction in the correctness of an already known and accepted position. An example pushes the thought to a new generalization and reinforces this generalization, an illustration clarifies a well-known general position, demonstrates its meaning with the help of a number of possible applications, enhances the effect of its presence in the minds of the audience. The difference between the tasks of the example and the illustration is related to the difference in the criteria for their selection. The example should look rather “solid”, unambiguously interpreted fact. An illustration has the right to cause slight doubts, but at the same time it should especially vividly influence the imagination of the audience, stop its attention on itself. An illustration, to a much lesser extent than an example, runs the risk of being misinterpreted, since behind it there is an already known position. The distinction between an example and an illustration is not always clear cut. Aristotle distinguished two uses of an example, depending on whether the speaker has any general principles or not: for a witness worthy of faith is useful even when he is alone.”

The role of special cases, according to Aristotle, is different depending on whether they precede the general position to which they refer, or follow it. The point, however, is that the facts given before the generalization are, as a rule, examples, while one or the few facts given after it are illustrations. This is also evidenced by Aristotle's warning that the listener's demands, for example, are higher than for illustrations. An unfortunate example casts doubt on the general position that it is intended to reinforce. A contradictory example can even refute this proposition. The situation is different with an unsuccessful, inadequate illustration: the general position to which it is given is not questioned, and an inadequate illustration is regarded rather as a negative characteristic of the one who applies it, indicating a lack of understanding of the general principle or his inability to choose a successful illustration. An inadequate illustration can have a comic effect: “You have to respect your parents. When one of them scolds you, immediately object to him. The ironic use of illustration is especially effective when describing a particular person: first, a positive characterization is given to this person, and then an incompatible characterization is given. Thus, in Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, Anthony, constantly reminding that Brutus is an honest man, cites one after another evidence of his ingratitude and betrayal.

Concretizing the general position with the help of a particular case, the illustration enhances the effect of presence. On this basis, it is sometimes seen as an image, a living picture of an abstract thought. The illustration, however, does not set itself the goal of replacing the abstract with the concrete and thereby transferring consideration to other objects. It does analogy, the illustration is nothing more than a special case, confirming the already known general position or facilitating its clearer understanding.

Often an illustration is chosen based on the emotional resonance it can evoke. This is what Aristotle does, for example, who prefers a periodical style to a coherent style that does not have a clearly visible end: “...because everyone wants to see the end; for this reason (competitors on the run) suffocate and weaken on the turns, while before they did not feel tired, seeing the limit of the run in front of them.

A comparison used in argumentation that is not a comparative assessment (preference) is usually an illustration of one case by another, while both cases are considered as concretizations of the same general principle. A typical example of comparison: “People are shown by circumstances. So, when some circumstance falls to you, remember that it was God, like a gymnastics teacher, who pushed you to a rough end.

5. Theoretical reasoning

All general provisions, scientific laws, principles, etc. cannot be substantiated purely empirically, by reference only to experience. They also require theoretical justification based on reasoning and referring us to other accepted statements. Without this, there is neither abstract theoretical knowledge nor firm, justified beliefs.

One of the important ways to theoretically substantiate the assertion is deriving it from some more general propositions. If the put forward assumption can be logically (deductively) deduced from some established truths, this means that it is true.

Suppose someone who is not familiar with the basics of the theory of electricity, conjectures that direct current is characterized not only by strength, but also by voltage. To confirm this conjecture, it is enough to open any reference book and find out that any current in general has a certain voltage. From this general position it follows that direct current also has voltage.

In Leo Tolstoy's story "The Death of Ivan Ilyich" there is an episode that is directly related to logic.

Ivan Ilyich felt that he was dying and was in constant despair. In an agonizing search for some kind of light, he even seized on his old idea that the rules of logic, which are always true for everyone, are inapplicable to him. “That example of the syllogism that he studied in logic: Kai is a man, people are mortal, therefore Kai is mortal, seemed to him throughout his life to be correct only in relation to Kai, but not to him. It was Kai - a man, a man in general, and it was absolutely fair; but he was not Kai and, in general, a man, but he was a very, very special being from all the others ... And Kai is definitely mortal, and it’s right for him to die, but not for me, Vanya, Ivan Ilyich, with all my feelings, thoughts, - for me it’s another thing. And it can't be that I should die. It would be too terrible."

The course of Ivan Ilyich's thoughts is dictated, of course, by the despair that gripped him. Only it gave rise to the idea that what is true always and for everyone will suddenly turn out to be inapplicable at a particular moment to a particular person. In a mind not terrified, such an assumption cannot even arise. However undesirable the consequences of our reasoning may be, they must be accepted if the premises are accepted.

Deductive reasoning is always coercion. When we think, we constantly feel pressure and unfreedom. It is no coincidence that Aristotle, who was the first to emphasize the unconditional nature of logical laws, noted with regret: “Thinking is suffering,” for “if a thing is necessary, it is a burden to us.”

Justifying the statement by deriving it from other accepted provisions, we do not make this statement absolutely reliable and irrefutable. But we fully transfer to it the degree of certainty that is inherent in the propositions accepted as premises of deduction. If, say, we are convinced that all people are mortal and that Ivan Ilyich, with all his particularity and uniqueness, is a man, we are obliged to admit that he is also mortal.

It may seem that deductive justification is, so to speak, the best of all possible methods of justification, since it imparts to the justified assertion the same firmness as the premises from which it is deduced. However, such an estimate would be clearly overstated. The derivation of new propositions from established truths finds only limited application in the process of substantiation. The most interesting and important statements that need to be substantiated are, as a rule, general and cannot be obtained as consequences of existing truths. Statements that require substantiation usually speak of relatively new phenomena that have not been studied in detail and are not yet covered by universal principles.

A substantiated statement must be in agreement with the factual material on the basis of which and for the explanation of which it is put forward. It must also correspond to the laws, principles, theories, etc. available in the area under consideration.. This is the so-called compatibility condition.

If, for example, someone proposes a detailed design of a perpetual motion machine, then we are primarily interested not in the subtleties of the design and not in its originality, but in whether its author is familiar with the law of conservation of energy. Energy, as is well known, does not arise from nothing and does not disappear without a trace, it only passes from one form to another. This means that a perpetual motion machine is incompatible with one of the fundamental laws of nature and, therefore, is in principle impossible, whatever its design.

Being fundamentally important, the condition of compatibility does not, of course, mean that every new provision should be required to fully, passively adapt to what is commonly considered "law" today. Like the correspondence with the facts, the correspondence with the theoretical truths found should not be interpreted too straightforwardly. It may happen that new knowledge will force us to take a different look at what was accepted before, to clarify or even discard something from the old knowledge. Consistency with accepted theories is reasonable as long as it is aimed at finding the truth, and not at maintaining the authority of the old theory.

If the compatibility condition is understood absolutely, then it excludes the possibility of intensive development of science. Science is given the opportunity to develop by extending already discovered laws to new phenomena, but it is deprived of the right to revise the already formulated provisions. But this is tantamount to a virtual denial of the development of science.

The new position should be in agreement not only with well-established theories, but also with certain general principles that have developed in the practice of scientific research. These principles are heterogeneous, they have varying degrees of generality and specificity, compliance with them is desirable, but not necessary.

The most famous of them is simplicity principle. It requires using as few independent assumptions as possible in explaining the phenomena under study, and the latter should be as simple as possible. The principle of simplicity runs through the history of the natural sciences. Many eminent naturalists pointed out that he repeatedly played a leading role in their research. In particular, I. Newton put forward a special requirement "not to overdo it" in the causes when explaining phenomena.

However, the concept of simplicity is not unambiguous. We can talk about the simplicity of the assumptions underlying the theoretical generalization, about the independence of such assumptions from each other. But simplicity can also be understood as ease of manipulation, ease of learning, etc. It is also not obvious that the desire to get by with a smaller number of premises, taken by itself, increases the reliability of the conclusion drawn from them.

“It would seem reasonable to look for the simplest solution,” writes the logician and philosopher W. Quine. “But this supposed property of simplicity is much easier to feel than to describe.” And yet, he continues, “the current standards of simplicity, difficult as they may be to formulate, are playing an increasingly important role. The competence of the scientist includes the generalization and extrapolation of exemplary data and, consequently, the comprehension of laws covering more phenomena than was taken into account; and simplicity in his understanding is precisely what serves as the basis for extrapolation. Simplicity refers to the essence of statistical inference. If a scientist's data is represented as points in a graph, and the law is to be represented as a curve through those points, then he draws the smoothest, simplest curve he can. He even slightly affects the points to simplify the task, justifying himself with inaccurate measurements. If he can get a simpler curve by omitting some points altogether, he tries to explain them in a special way… Whatever simplicity is, it is not just a hobby.”

Another general principle often used in evaluating the assumptions put forward is the so-called familiarity principle. He recommends avoiding unjustified innovations and trying, as far as possible, to explain new phenomena with the help of known laws. “The usefulness of the habitual principle for the continuous activity of the creative imagination,” writes W. Quine, “is a kind of paradox. Conservatism, preferring an inherited or developed conceptual scheme to one's own work done, is both a defense of laziness and a strategy of discovery. If, however, simplicity and conservatism give opposite recommendations, simplicity should be preferred.

The picture of the world developed by science is not unambiguously predetermined by the studied objects themselves. Under these conditions of incomplete certainty, a variety of general recommendations are unfolding, helping to choose one of several competing ideas about the world.

Another way of theoretical substantiation is analysis of the statement in terms of the possibility of its empirical confirmation and refutation.

Scientific statements are required to admit the fundamental possibility of refutation and to presuppose certain procedures for their confirmation. If this is not the case, it is impossible to say with respect to the proposition put forward which situations and facts are incompatible with it, and which ones support it. The position, which in principle does not allow refutation and confirmation, turns out to be beyond constructive criticism; it does not outline any real ways for further research. An assertion that is incomparable either with experience or with existing knowledge cannot, of course, be recognized as justified.

If someone predicts that tomorrow it will rain or it will not rain, then this assumption is fundamentally impossible to refute. It will be true both if it rains the next day, and if it does not. At any time, regardless of the weather, it either rains or it doesn't. It will never be possible to refute this kind of "weather forecast". It also cannot be confirmed.

It can hardly be called justified and the assumption that in exactly ten years in the same place it will be sunny and dry. It is not based on any facts, one cannot even imagine how it could be refuted or confirmed, if not now, then at least in the near future.

At the beginning of this century, the biologist G. Driesch tried to introduce some kind of hypothetical "life force" inherent only in living beings and forcing them to behave the way they behave. This force - Driesch called it "entelechy" - supposedly has different types, depending on the stage of development of organisms. In the simplest unicellular organisms, entelechy is comparatively simple. In humans, it is much larger than the mind, because it is responsible for everything that every cell does in the body. Driesch did not define how the entelechy of, say, an oak differs from that of a goat or a giraffe. He simply said that every organism has its own entelechy. He interpreted the ordinary laws of biology as manifestations of entelechy. If you cut off a limb from a sea urchin in a certain way, then the urchin will not survive. If cut off in another way, the hedgehog will survive, but it will grow only an incomplete limb. If the incision is made differently and at a certain stage of sea urchin growth, then the limb will recover completely. All these relationships, known to zoologists, Driesch interpreted as evidence of the action of entelechy.

Could the existence of a mysterious "life force" be tested experimentally? No, because it did not manifest itself in anything other than the known and explainable and without it. She added nothing to the scientific explanation, and no concrete facts could touch her. The entelechy hypothesis, which had no fundamental possibility of empirical confirmation, was soon abandoned as useless.

Another example of a fundamentally unverifiable assertion is the assumption about the existence of supernatural, non-material objects that do not manifest themselves in any way and do not reveal themselves in any way.

Propositions that, in principle, cannot be verified must, of course, be distinguished from statements that cannot be verified only today, at the current level of development of science. A little over a hundred years ago, it seemed obvious that we would never know the chemical composition of distant celestial bodies. Various hypotheses on this score seemed fundamentally untestable. But after the creation of spectroscopy, they became not only testable, but also ceased to be hypotheses, turning into experimentally established facts.

Assertions that cannot be checked immediately are not discarded if it is possible in principle to check them in the future. But usually such claims do not become the subject of serious scientific discussions.

This is the case, for example, with the assumption of the existence of extraterrestrial civilizations, the practical possibility of testing which is still negligible.

The methods of theoretical substantiation also include checking the put forward position for its applicability to a wide class of objects under study.. If a statement that is true for one area turns out to be sufficiently universal and leads to new conclusions not only in the original, but also in related areas, its objective significance increases markedly. The tendency to expansion, to expand the scope of its applicability is inherent in all fruitful scientific generalizations to a greater or lesser extent.

A good example here is the quantum hypothesis put forward by M. Planck. At the end of the last century, physicists faced the problem of the radiation of the so-called absolutely black body, i.e. a body that absorbs all radiation falling on it and reflects nothing. In order to avoid infinite quantities of radiated energy that have no physical meaning, Planck assumed that energy is not emitted continuously, but in separate discrete portions - quanta. At first glance, the hypothesis seemed to explain one relatively common phenomenon - the radiation of a completely black body. But if this were indeed the case, then the quantum hypothesis would hardly have survived in science. In fact, the introduction of quanta proved to be extraordinarily fruitful and quickly spread to a number of other areas. Based on the idea of quanta, A. Einstein developed the theory of the photoelectric effect, and N. Bohr developed the theory of the hydrogen atom. In a short time, the quantum hypothesis explained from one basis an extremely wide field of very different phenomena.

The expansion of the field of action of the statement, its ability to explain and predict completely new facts is an undoubted and important argument in its support. The confirmation of some scientific position by facts and experimental laws, the existence of which before its nomination could not even be assumed, directly indicates that this position captures the deep inner relationship of the phenomena under study.

It is difficult to name a statement that would justify itself, in isolation from other statements. Justification is always systemic character. The inclusion of a new provision in a system of other provisions that gives stability to its elements is one of the most important steps in its justification..

Confirmation of the consequences arising from a theory is at the same time a reinforcement of the theory itself. On the other hand, the theory imparts certain impulses and force to the propositions put forward on its basis, and thereby contributes to their justification. An assertion that has become part of a theory is no longer based only on individual facts, but in many respects also on a wide range of phenomena explained by the theory, on its prediction of new, previously unknown effects, on its connections with other scientific theories, etc. Having included the analyzed position in the theory, we thereby extend to it the empirical and theoretical support that the theory as a whole has.

This point has been noted more than once by philosophers and scientists who have been thinking about the justification of knowledge.

Thus, the philosopher L. Wittgenstein wrote about the integrity and systemic nature of knowledge: “It is not an isolated axiom that strikes me as obvious, but a whole system in which consequences and premises mutually support each other.” Consistency extends not only to theoretical positions, but also to the data of experience: “It can be said that experience teaches us some statements. However, he does not teach us isolated statements, but a whole set of interdependent propositions. If they were separate, I might doubt them, because I have no experience directly related to each of them. The foundations of a system of assertions, Wittgenstein notes, do not support this system, but are themselves supported by it. This means that the reliability of the foundations is determined not by them in themselves, but by the fact that an integral theoretical system can be built on top of them. The "foundation" of knowledge appears to be hanging in the air until a stable building is built on it. The claims of scientific theory are mutually intertwined and support each other. They hold on like people on a crowded bus when propped up on all sides, and they don't fall because there is nowhere to fall.

Since the theory gives additional support to its claims, improvement of the theory, strengthening of its empirical base and clarification of its general, including philosophical prerequisites, is at the same time a contribution to the substantiation of the statements included in it.

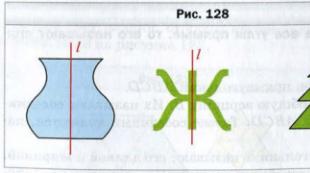

Among the methods of clarifying a theory, a special role is played by revealing the logical connections of its statements, minimizing its initial assumptions, constructing it in the form of an axiomatic system, and, finally, if possible, its formalization.

At axiomatizations theory, some of its provisions are chosen as initial ones, and all other provisions are derived from them in a purely logical way. Assumptions accepted without proof are called axioms(postulates), the provisions proved on their basis - theorems.

The axiomatic method of systematization and clarification of knowledge originated in antiquity and gained great fame thanks to Euclid's "Principles" - the first axiomatic interpretation of geometry. Now axiomatization is used in mathematics, logic, as well as in certain sections of physics, biology, etc. The axiomatic method requires a high level of development of an axiomatizable content theory, clear logical connections of its statements. Associated with this is its rather narrow applicability and the naivety of attempts to rebuild any science along the lines of Euclid's geometry.

In addition, as the logician and mathematician K. Gödel showed, sufficiently rich scientific theories (for example, the arithmetic of natural numbers) do not allow complete axiomatization. This indicates the limitations of the axiomatic method and the impossibility of a complete formalization of scientific knowledge.

Methodological argumentation is the substantiation of a single statement or a holistic concept by referring to the undoubtedly reliable method by which the justified statement or defended concept was obtained.

Ideas about the scope of methodological argumentation have changed from one era to another. Significant importance was attached to it in modern times, when it was believed that it was the methodological guarantee, and not the correspondence to the facts as such, that gave the judgment its validity. The modern methodology of science is skeptical of the view that strict adherence to method can itself provide truth and serve as its reliable justification. The possibilities of methodological argumentation are different in different fields of knowledge. References to the method by which a specific conclusion is obtained are common in the natural sciences, but extremely rare in the humanities and almost never found in practical and even more artistic thinking.