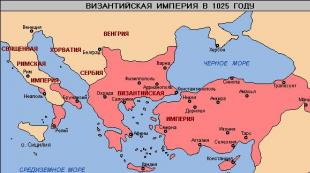

Byzantine Empire (395-1453). Byzantine Empire Map of Byzantium in the 11th century

The great influence that the Byzantine Empire had on the history (as well as religion, culture, art) of many European countries (including ours) in the era of the gloomy Middle Ages is difficult to cover in one article. But we will still try to do this, and tell you as much as possible about the history of Byzantium, its way of life, culture and much more, in a word, using our time machine to send you to the time of the highest heyday of the Byzantine Empire, so get comfortable and let's go.

Where is Byzantium

But before going on a journey through time, first let's deal with the movement in space, and determine where is (or rather was) Byzantium on the map. In fact, at different points in historical development, the boundaries of the Byzantine Empire were constantly changing, expanding during periods of development and shrinking during periods of decline.

For example, this map shows Byzantium in its heyday, and as we can see at that time, it occupied the entire territory of modern Turkey, part of the territory of modern Bulgaria and Italy, and numerous islands in the Mediterranean Sea.

During the reign of Emperor Justinian, the territory of the Byzantine Empire was even larger, and the power of the Byzantine emperor also extended to North Africa (Libya and Egypt), the Middle East, (including the glorious city of Jerusalem). But gradually they began to be ousted from there first, with whom Byzantium was in a state of permanent war for centuries, and then the militant Arab nomads, carrying in their hearts the banner of a new religion - Islam.

And here the map shows the possessions of Byzantium at the time of its decline, in 1453, as we see at that time its territory was reduced to Constantinople with the surrounding territories and part of modern Southern Greece.

History of Byzantium

The Byzantine Empire is the successor of another great empire -. In 395, after the death of the Roman Emperor Theodosius I, the Roman Empire was divided into Western and Eastern. This separation was caused by political reasons, namely, the emperor had two sons, and probably, so as not to deprive any of them, the eldest son Flavius became the emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire, and the youngest son Honorius, respectively, the emperor of the Western Roman Empire. At first, this division was purely nominal, and in the eyes of millions of citizens of the superpower of antiquity, it was still the same one big Roman Empire.

But as we know, the Roman Empire gradually began to lean towards its death, which was largely facilitated by both the decline in morals in the empire itself and the waves of warlike barbarian tribes that now and then rolled onto the borders of the empire. And already in the 5th century, the Western Roman Empire finally fell, the eternal city of Rome was captured and plundered by the barbarians, the end came in the era of antiquity, the Middle Ages began.

But the Eastern Roman Empire, thanks to a happy coincidence, survived, the center of its cultural and political life was concentrated around the capital of the new empire, Constantinople, which became the largest city in Europe in the Middle Ages. The waves of barbarians passed by, although, of course, they also had their influence, but for example, the rulers of the Eastern Roman Empire prudently preferred to pay off gold rather than fight from the ferocious conqueror Attila. Yes, and the destructive impulse of the barbarians was directed precisely at Rome and the Western Roman Empire, which saved the Eastern Empire, from which, after the fall of the Western Empire in the 5th century, a new great state of Byzantium or the Byzantine Empire was formed.

Although the population of Byzantium consisted mainly of Greeks, they always felt themselves to be the heirs of the great Roman Empire and called them accordingly - "Romans", which in Greek means "Romans".

Since the 6th century, during the reign of the brilliant emperor Justinian and his no less brilliant wife (our website has an interesting article about this “first lady of Byzantium”, follow the link), the Byzantine Empire begins to slowly recapture the territories once occupied by barbarians. So the Byzantines from the barbarians of the Lombards captured significant territories of modern Italy, which once belonged to the Western Roman Empire, the power of the Byzantine emperor extends to northern Africa, the local city of Alexandria becomes an important economic and cultural center of the empire in this region. The military campaigns of Byzantium extend to the East, where for several centuries there have been continuous wars with the Persians.

The very geographical position of Byzantium, which spread its possessions on three continents at once (Europe, Asia, Africa), made the Byzantine Empire a kind of bridge between the West and the East, a country in which the cultures of different peoples were mixed. All this left its mark on social and political life, religious and philosophical ideas and, of course, art.

Conventionally, historians divide the history of the Byzantine Empire into five periods, we give a brief description of them:

- The first period of the initial heyday of the empire, its territorial expansion under the emperors Justinian and Heraclius lasted from the 5th to the 8th century. During this period, there is an active dawn of the Byzantine economy, culture, and military affairs.

- The second period began with the reign of the Byzantine emperor Leo III the Isaurian and lasted from 717 to 867. At this time, the empire, on the one hand, reaches the greatest development of its culture, but on the other hand, it is overshadowed by numerous turmoils, including religious ones (iconoclasm), which we will write about in more detail later.

- The third period is characterized on the one hand by the end of unrest and the transition to relative stability, on the other hand by constant wars with external enemies, it lasted from 867 to 1081. Interestingly, during this period, Byzantium was actively at war with its neighbors, the Bulgarians and our distant ancestors, the Russians. Yes, it was during this period that the campaigns of our Kyiv princes Oleg (Prophetic), Igor, Svyatoslav against Constantinople (as the capital of Byzantium Constantinople was called in Rus') took place.

- The fourth period began with the reign of the Komnenos dynasty, the first emperor Alexei Komnenos ascended the Byzantine throne in 1081. Also, this period is known as the "Comnian Renaissance", the name speaks for itself, during this period Byzantium revives its cultural and political greatness, somewhat faded after unrest and constant wars. The Comneni turned out to be wise rulers, skillfully balancing in those difficult conditions in which Byzantium found itself at that time: from the East, the borders of the empire were increasingly pressed by the Seljuk Turks, from the West, Catholic Europe was breathing, considering the Orthodox Byzantines apostates and heretics, which is little better than infidel Muslims.

- The fifth period is characterized by the decline of Byzantium, which, as a result, led to its death. It lasted from 1261 to 1453. During this period, Byzantium is waging a desperate and unequal struggle for survival. The growing strength of the Ottoman Empire, the new, this time the Muslim superpower of the Middle Ages, finally swept away Byzantium.

Fall of Byzantium

What are the main reasons for the fall of Byzantium? Why did an empire that owned such vast territories and such power (both military and cultural) fall? First of all, the most important reason was the strengthening of the Ottoman Empire, in fact, Byzantium became one of their first victims, subsequently the Ottoman Janissaries and Sipahs would shake many other European nations on their nerves, even reaching Vienna in 1529 (from where they were knocked out only by the combined efforts of the Austrian and the Polish troops of King Jan Sobieski).

But in addition to the Turks, Byzantium also had a number of internal problems, constant wars exhausted this country, many territories that it owned in the past were lost. The conflict with Catholic Europe also had an effect, resulting in a fourth one, directed not against infidel Muslims, but against the Byzantines, these "wrong Orthodox Christian heretics" (from the point of view of Catholic crusaders, of course). Needless to say, the fourth crusade, which resulted in the temporary conquest of Constantinople by the crusaders and the formation of the so-called "Latin Republic" was another important reason for the subsequent decline and fall of the Byzantine Empire.

Also, the fall of Byzantium was greatly facilitated by the numerous political unrest that accompanied the final fifth stage in the history of Byzantium. So, for example, the Byzantine emperor John Palaiologos V, who ruled from 1341 to 1391, was overthrown from the throne three times (it is interesting that first by his father-in-law, then by his son, then by his grandson). The Turks, on the other hand, skillfully used the intrigues at the court of the Byzantine emperors for their own selfish purposes.

In 1347, the worst epidemic of the plague swept through the territory of Byzantium, black death, as this disease was called in the Middle Ages, the epidemic claimed about a third of the inhabitants of Byzantium, which was another reason for the weakening and fall of the empire.

When it became clear that the Turks were about to sweep away Byzantium, the latter began again to seek help from the West, but relations with the Catholic countries, as well as the Pope of Rome, were more than strained, only Venice came to the rescue, whose merchants traded profitably with Byzantium, and in Constantinople itself even had a whole Venetian merchant quarter. At the same time, Genoa, the former trade and political opponent of Venice, on the contrary, helped the Turks in every possible way and was interested in the fall of Byzantium (primarily with the aim of causing problems to its commercial competitors, the Venetians). In a word, instead of uniting and helping Byzantium resist the attack of the Ottoman Turks, the Europeans pursued their own interests, a handful of Venetian soldiers and volunteers, yet sent to help Constantinople besieged by the Turks, could not do anything.

On May 29, 1453, the ancient capital of Byzantium, the city of Constantinople, fell (later renamed Istanbul by the Turks), and the once great Byzantium fell with it.

Byzantine culture

The culture of Byzantium is the product of a mixture of cultures of many peoples: Greeks, Romans, Jews, Armenians, Egyptian Copts and the first Syrian Christians. The most striking part of Byzantine culture is its ancient heritage. Many traditions from the time of ancient Greece were preserved and transformed in Byzantium. So the spoken written language of the citizens of the empire was precisely Greek. The cities of the Byzantine Empire retained Greek architecture, the structure of Byzantine cities, again borrowed from ancient Greece: the heart of the city was the agora - a wide square where public meetings were held. The cities themselves were lavishly decorated with fountains and statues.

The best masters and architects of the empire built the palaces of the Byzantine emperors in Constantinople, the most famous among them is the Great Imperial Palace of Justinian.

The remains of this palace in a medieval engraving.

Ancient crafts continued to develop actively in Byzantine cities, the masterpieces of the local jewelers, craftsmen, weavers, blacksmiths, artists were valued throughout Europe, the skills of Byzantine masters were actively adopted by representatives of other peoples, including the Slavs.

Of great importance in the social, cultural, political and sports life of Byzantium were hippodromes, where chariot races were held. For the Romans, they were about the same as football is for many today. There were even their own, in modern terms, fan clubs rooting for one or another team of chariot hounds. Just as modern ultras football fans who support different football clubs from time to time arrange fights and brawls among themselves, the Byzantine fans of chariot racing were also very eager for this matter.

But besides just unrest, various groups of Byzantine fans also had a strong political influence. So once an ordinary brawl of fans at the hippodrome led to the largest uprising in the history of Byzantium, known as "Nika" (literally "win", this was the slogan of the rebellious fans). The uprising of Nika's supporters almost led to the overthrow of Emperor Justinian. Only thanks to the determination of his wife Theodora and the bribery of the leaders of the uprising, he was able to suppress.

Hippodrome in Constantinople.

In the jurisprudence of Byzantium, Roman law, inherited from the Roman Empire, reigned supreme. Moreover, it was in the Byzantine Empire that the theory of Roman law acquired its final form, such key concepts as law, law, and custom were formed.

The economy in Byzantium was also largely driven by the legacy of the Roman Empire. Each free citizen paid taxes to the treasury from his property and labor activity (a similar tax system was also practiced in ancient Rome). High taxes often became the cause of mass discontent, and even unrest. Byzantine coins (known as Roman coins) circulated throughout Europe. These coins were very similar to the Roman ones, but the Byzantine emperors made only a number of minor changes to them. The first coins that began to be minted in the countries of Western Europe, in turn, were an imitation of Roman coins.

This is what coins looked like in the Byzantine Empire.

Religion, of course, had a great influence on the culture of Byzantium, about which read on.

Religion of Byzantium

In religious terms, Byzantium became the center of Orthodox Christianity. But before that, it was on its territory that the most numerous communities of the first Christians were formed, which greatly enriched its culture, especially in terms of the construction of temples, as well as in the art of icon painting, which originated precisely in Byzantium.

Gradually, Christian churches became the center of the public life of Byzantine citizens, pushing aside the ancient agoras and hippodromes with their violent fans in this regard. Monumental Byzantine churches, built in the 5th-10th centuries, combine both ancient architecture (from which Christian architects borrowed a lot of things) and already Christian symbolism. The most beautiful temple creation in this regard can rightfully be considered the Church of St. Sophia in Constantinople, which was later converted into a mosque.

Art of Byzantium

The art of Byzantium was inextricably linked with religion, and the most beautiful thing that it gave to the world was the art of icon painting and the art of mosaic frescoes, which adorned many churches.

True, one of the political and religious unrest in the history of Byzantium, known as Iconoclasm, was connected with icons. This was the name of the religious and political trend in Byzantium, which considered icons to be idols, and therefore subject to extermination. In 730 Emperor Leo III the Isaurian officially banned the veneration of icons. As a result, thousands of icons and mosaics were destroyed.

Subsequently, the power changed, in 787 Empress Irina ascended the throne, who returned the veneration of icons, and the art of icon painting was revived with the same strength.

The art school of Byzantine icon painters set the traditions of icon painting for the whole world, including its great influence on the art of icon painting in Kievan Rus.

Byzantium, video

And finally, an interesting video about the Byzantine Empire.

We do not recognize Byzantium in early Byzantine history with its praetors, prefects, patricians and provinces, but this recognition will become more and more as emperors acquire beards, consuls turn into hypats, and senators into synclitics.

background

The birth of Byzantium will not be clear without a return to the events of the 3rd century, when the most severe economic and political crisis broke out in the Roman Empire, which actually led to the collapse of the state. In 284, Diocletian came to power (like almost all emperors of the 3rd century, he was just a Roman officer of humble origin - his father was a slave) and took measures to decentralize power. First, in 286, he divided the empire into two parts, entrusting the administration of the West to his friend Maximian Herculius, while keeping the East for himself. Then, in 293, wanting to increase the stability of the system of government and ensure the turnover of power, he introduced a system of tetrarchy - a four-part government, which was carried out by two senior Augustus emperors and two junior Caesar emperors. Each part of the empire had an August and a Caesar (each of which had its own geographical area of responsibility - for example, the August of the West controlled Italy and Spain, and the Caesar of the West controlled Gaul and Britain). After 20 years, the Augusts were to transfer power to the Caesars, so that they would become Augusts and elect new Caesars. However, this system proved unviable, and after the abdication of Diocletian and Maximian in 305, the empire again plunged into an era of civil wars.

Birth of Byzantium

1. 312 - Battle of the Mulvian Bridge

After the abdication of Diocletian and Maximian, the supreme power passed to the former Caesars - Galerius and Constantius Chlorus, they became Augusts, but neither the son of Constantius Constantine (later Emperor Constantine I the Great, considered the first emperor of Byzantium), nor Maximian's son Maxentius. Nevertheless, both of them did not leave imperial ambitions and from 306 to 312 alternately entered into a tactical alliance in order to jointly oppose other contenders for power (for example, Flavius Severus, appointed Caesar after the abdication of Diocletian), then, on the contrary, entered the struggle. The final victory of Constantine over Maxentius in the battle on the Milvian bridge across the Tiber River (now within the boundaries of Rome) meant the unification of the western part of the Roman Empire under the rule of Constantine. Twelve years later, in 324, as a result of another war (now with Licinius - Augustus and the ruler of the East of the empire, who was appointed by Galerius), Constantine united East and West.

The miniature in the center depicts the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. From the homily of Gregory the Theologian. 879-882 years

The miniature in the center depicts the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. From the homily of Gregory the Theologian. 879-882 years

MS grec 510 /

The Battle of the Milvian Bridge in the Byzantine mind was associated with the idea of the birth of the Christian empire. This was facilitated, firstly, by the legend of the miraculous sign of the Cross, which Constantine saw in the sky before the battle - Eusebius of Caesarea tells about this (albeit in completely different ways). Eusebius of Caesarea(c. 260-340) - Greek historian, author of the first church history. and Lactants lactation(c. 250---325) - Latin writer, apologist for Christianity, author of the essay "On the Death of the Persecutors", dedicated to the events of the era of Diocletian., and secondly, the fact that two edicts were issued at about the same time Edict- normative act, decree. about religious freedom, legalized Christianity and equalized all religions in rights. And although the publication of edicts on religious freedom was not directly related to the fight against Maxentius (the first one was published in April 311 by Emperor Galerius, and the second - already in February 313 in Milan by Constantine together with Licinius), the legend reflects the internal connection of seemingly independent political steps of Constantine, who was the first to feel that state centralization is impossible without the consolidation of society, primarily in the sphere of worship.

However, under Constantine Christianity was only one of the candidates for the role of a consolidating religion. The emperor himself was for a long time an adherent of the cult of the Invincible Sun, and the time of his Christian baptism is still the subject of scientific disputes.

2. 325 - I Ecumenical Council

In 325 Constantine summoned representatives of the local churches to the city of Nicaea. Nicaea- now the city of Iznik in Northwestern Turkey. to resolve a dispute between Bishop Alexander of Alexandria and Arius, a presbyter of one of the Alexandrian churches, about whether Jesus Christ was created by God Opponents of the Arians briefly summarized their teaching thus: "There was [such a time] when [Christ] did not exist.". This meeting was the first Ecumenical Council - a meeting of representatives of all local churches, with the right to formulate doctrine, which will then be recognized by all local churches. It is impossible to say exactly how many bishops participated in the council, since its acts have not been preserved. Tradition calls the number 318. Be that as it may, it is possible to speak about the “ecumenical” nature of the cathedral only with reservations, since in total at that time there were more than 1,500 episcopal sees.. The First Ecumenical Council is a key stage in the institutionalization of Christianity as an imperial religion: its meetings were held not in the temple, but in the imperial palace, the cathedral was opened by Constantine I himself, and the closing was combined with grandiose celebrations on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of his reign.

First Council of Nicaea. Fresco from the monastery of Stavropoleos. Bucharest, 18th century

First Council of Nicaea. Fresco from the monastery of Stavropoleos. Bucharest, 18th century

Wikimedia Commons

Councils I of Nicaea and the Councils of Constantinople that followed it (meeting in 381) condemned the Arian doctrine about the created nature of Christ and the inequality of the hypostases in the Trinity, and the Apollinarian one, about the incomplete perception of human nature by Christ, and formulated the Nicene-Tsargrad Creed, which recognized Jesus Christ not created, but born (but at the same time eternal), but all three hypostases - possessing one nature. The creed was recognized as true, not subject to further doubt and discussion The words of the Nicene-Tsargrad Creed about Christ, which caused the most fierce disputes, in the Slavonic translation sound like this: Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten, uncreated, consubstantial with the Father, Whom all was.”.

Never before has any direction of thought in Christianity been condemned by the fullness of the universal church and imperial power, and no theological school has been recognized as heresy. The era of the Ecumenical Councils that has begun is the era of the struggle between orthodoxy and heresy, which are in constant self- and mutual determination. At the same time, the same doctrine could alternately be recognized as heresy, then right faith - depending on the political situation (this was the case in the 5th century), however, the very idea of the possibility and necessity of protecting orthodoxy and condemning heresy with the help of the state was questioned in Byzantium has never been set.

3. 330 - transfer of the capital of the Roman Empire to Constantinople

Although Rome always remained the cultural center of the empire, the Tetrarchs chose cities on the periphery as their capitals, from which it was more convenient for them to repel external attacks: Nicomedia Nicomedia- now Izmit (Türkiye)., Sirmium Sirmium- now Sremska Mitrovica (Serbia)., Milan and Trier. During the reign of the West, Constantine I transferred his residence to Milan, then to Sirmium, then to Thessalonica. His rival Licinius also changed the capital, but in 324, when a war broke out between him and Constantine, the ancient city of Byzantium on the banks of the Bosphorus, known from Herodotus, became his stronghold in Europe.

Sultan Mehmed II the Conqueror and the Serpent Column. Miniature of Naqqash Osman from the manuscript "Khyuner-name" by Seyid Lokman. 1584-1588 years

Sultan Mehmed II the Conqueror and the Serpent Column. Miniature of Naqqash Osman from the manuscript "Khyuner-name" by Seyid Lokman. 1584-1588 years Wikimedia Commons

During the siege of Byzantium, and then in preparation for the decisive battle of Chrysopolis on the Asian coast of the strait, Constantine assessed the position of Byzantium and, having defeated Licinius, immediately began a program to renew the city, personally participating in the marking of the city walls. The city gradually took over the functions of the capital: a senate was established in it and many Roman senatorial families were forcibly transported closer to the senate. It was in Constantinople that during his lifetime Constantine ordered to rebuild a tomb for himself. Various curiosities of the ancient world were brought to the city, for example, the bronze Serpentine Column, created in the 5th century BC in honor of the victory over the Persians at Plataea Battle of Plataea(479 BC) — one of the most important battles of the Greco-Persian wars, as a result of which the land forces of the Achaemenid Empire were finally defeated..

The 6th-century chronicler John Malala tells that on May 11, 330, Emperor Constantine appeared at the solemn ceremony of consecrating the city in a diadem - a symbol of the power of the eastern despots, which his Roman predecessors avoided in every possible way. The shift in the political vector was symbolically embodied in the spatial movement of the center of the empire from west to east, which, in turn, had a decisive influence on the formation of Byzantine culture: the transfer of the capital to territories that had been speaking Greek for a thousand years determined its Greek-speaking character, and Constantinople itself turned out to be in the center of the mental map of the Byzantine and identified with the entire empire.

4. 395 - division of the Roman Empire into Eastern and Western

Despite the fact that in 324 Constantine, having defeated Licinius, formally united the East and West of the empire, ties between its parts remained weak, and cultural differences grew. No more than ten bishops arrived at the First Ecumenical Council from the western provinces (out of about 300 participants); most of the arrivals were not able to understand Constantine's welcoming speech, which he delivered in Latin, and it had to be translated into Greek.

Half silicone. Flavius Odoacer on the obverse of a coin from Ravenna. 477 year Odoacer is depicted without the imperial diadem - with an uncovered head, a shock of hair and a mustache. Such an image is uncharacteristic for emperors and is considered "barbaric".

Half silicone. Flavius Odoacer on the obverse of a coin from Ravenna. 477 year Odoacer is depicted without the imperial diadem - with an uncovered head, a shock of hair and a mustache. Such an image is uncharacteristic for emperors and is considered "barbaric". The Trustees of the British Museum

The final division occurred in 395, when Emperor Theodosius I the Great, who for several months before his death became the sole ruler of East and West, divided the state between his sons Arcadius (East) and Honorius (West). However, formally the West still remained connected with the East, and at the very decline of the Western Roman Empire, in the late 460s, the Byzantine emperor Leo I, at the request of the Senate of Rome, made the last unsuccessful attempt to elevate his protege to the western throne. In 476, the German barbarian mercenary Odoacer deposed the last emperor of the Roman Empire, Romulus Augustulus, and sent the imperial insignia (symbols of power) to Constantinople. Thus, from the point of view of the legitimacy of power, parts of the empire were again united: the emperor Zeno, who ruled at that time in Constantinople, de jure became the sole head of the entire empire, and Odoacer, who received the title of patrician, ruled Italy only as his representative. However, in reality, this was no longer reflected in the real political map of the Mediterranean.

5. 451 - Chalcedon Cathedral

IV Ecumenical (Chalcedon) Council, convened for the final approval of the doctrine of the incarnation of Christ in a single hypostasis and two natures and the complete condemnation of Monophysitism Monophysitism(from the Greek μόνος - the only one and φύσις - nature) - the doctrine that Christ did not have a perfect human nature, since his divine nature, during the incarnation, replaced it or merged with it. The opponents of the Monophysites were called dyophysites (from the Greek δύο - two)., led to a deep schism that has not been overcome by the Christian church to this day. The central government continued to flirt with the Monophysites under the usurper Basiliscus in 475-476, and in the first half of the 6th century, under the emperors Anastasius I and Justinian I. Emperor Zeno in 482 tried to reconcile the supporters and opponents of the Council of Chalcedon, without going into dogmatic issues . His conciliatory message, called the Enoticon, ensured peace in the East, but led to a 35-year split with Rome.The main support of the Monophysites were the eastern provinces - Egypt, Armenia and Syria. Religious uprisings regularly broke out in these regions and an independent Monophysite hierarchy and its own church institutions parallel to the Chalcedonian (that is, recognizing the teachings of the Council of Chalcedon) and their own church institutions were formed, which gradually developed into independent, non-Chalcedonian churches that still exist today - Syro-Jacobite, Armenian and Coptic. The problem finally lost its relevance for Constantinople only in the 7th century, when, as a result of the Arab conquests, the Monophysite provinces were torn away from the empire.

Rise of early Byzantium

6. 537 - completion of the construction of the church of Hagia Sophia under Justinian

Justinian I. Fragment of the church mosaic

Justinian I. Fragment of the church mosaic San Vitale in Ravenna. 6th century

Wikimedia Commons

Under Justinian I (527-565), the Byzantine Empire reached its peak. The Code of Civil Law summarized the centuries-old development of Roman law. As a result of military campaigns in the West, it was possible to expand the borders of the empire, including the entire Mediterranean - North Africa, Italy, part of Spain, Sardinia, Corsica and Sicily. Sometimes people talk about the "Justinian Reconquista". Rome became part of the empire again. Justinian launched extensive construction throughout the empire, and in 537 the construction of a new Hagia Sophia in Constantinople was completed. According to legend, the plan of the temple was suggested personally to the emperor by an angel in a vision. Never again in Byzantium was a building of such magnitude built: a grandiose temple, in the Byzantine ceremonial called the "Great Church", became the center of power of the Patriarchate of Constantinople.

The era of Justinian at the same time and finally breaks with the pagan past (in 529 the Academy of Athens was closed Athens Academy - philosophical school in Athens, founded by Plato in the 380s BC. e.) and establishes a line of succession with antiquity. Medieval culture opposes itself to early Christian culture, appropriating the achievements of antiquity at all levels - from literature to architecture, but at the same time discarding their religious (pagan) dimension.

Coming from the bottom, seeking to change the way of life of the empire, Justinian met with rejection from the old aristocracy. It is this attitude, and not the personal hatred of the historian for the emperor, that is reflected in the vicious pamphlet on Justinian and his wife Theodora.

7. 626 - Avaro-Slavic siege of Constantinople

The reign of Heraclius (610-641), glorified in court panegyric literature as the new Hercules, accounted for the last foreign policy successes of early Byzantium. In 626, Heraclius and Patriarch Sergius, who was directly defending the city, managed to repel the Avar-Slavic siege of Constantinople (the words that open the akathist to the Mother of God tell precisely about this victory In the Slavic translation, they sound like this: “To the chosen Voivode, victorious, as if having got rid of the evil ones, we thankfully describe Thy servants, the Mother of God, but as if having an invincible power, free us from all troubles, let us call Ty: rejoice, Bride of the Bride.”), and at the turn of the 20-30s of the 7th century during the Persian campaign against the power of the Sassanids Sasanian Empire- a Persian state centered on the territory of present-day Iraq and Iran, which existed in the years 224-651. the provinces in the East lost a few years earlier were recaptured: Syria, Mesopotamia, Egypt and Palestine. The Holy Cross stolen by the Persians was solemnly returned to Jerusalem in 630, on which the Savior died. During the solemn procession, Heraclius personally brought the Cross into the city and laid it in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher.

Under Heraclius, the last rise before the cultural break of the Dark Ages is experienced by the scientific and philosophical Neoplatonic tradition, coming directly from antiquity: a representative of the last surviving ancient school in Alexandria, Stephen of Alexandria, comes to Constantinople at the imperial invitation to teach.

Plate from a cross with images of a cherub (left) and the Byzantine emperor Heraclius with the Shahinshah of the Sassanids Khosrow II. Valley of the Meuse, 1160-70s

Plate from a cross with images of a cherub (left) and the Byzantine emperor Heraclius with the Shahinshah of the Sassanids Khosrow II. Valley of the Meuse, 1160-70s Wikimedia Commons

All these successes were brought to naught by the Arab invasion, which wiped out the Sassanids from the face of the earth in a few decades and forever wrested the eastern provinces from Byzantium. Legends tell how the prophet Muhammad offered Heraclius to convert to Islam, but in the cultural memory of the Muslim peoples, Heraclius remained precisely a fighter against the emerging Islam, and not with the Persians. These wars (generally unsuccessful for Byzantium) are described in the 18th-century epic poem The Book of Heraclius, the oldest written monument in Swahili.

Dark Ages and Iconoclasm

8. 642 Arab conquest of Egypt

The first wave of Arab conquests in the Byzantine lands lasted eight years - from 634 to 642. As a result, Mesopotamia, Syria, Palestine and Egypt were torn away from Byzantium. Having lost the most ancient Patriarchates of Antioch, Jerusalem and Alexandria, the Byzantine Church, in fact, lost its universal character and became equal to the Patriarchate of Constantinople, which within the empire had no church institutions equal to it in status.

In addition, having lost the fertile territories that provided it with grain, the empire plunged into a deep internal crisis. In the middle of the 7th century, there was a reduction in monetary circulation and the decline of cities (both in Asia Minor and in the Balkans, which were no longer threatened by the Arabs, but by the Slavs) - they turned into either villages or medieval fortresses. Constantinople remained the only major urban center, but the atmosphere in the city changed and the ancient monuments brought there back in the 4th century began to inspire irrational fears in the townspeople.

Fragment of a papyrus letter in the Coptic language of the monks Victor and Psan. Thebes, Byzantine Egypt, circa 580-640 Translation of a fragment of a letter into English at the Metropolitan Museum of Art website.

Fragment of a papyrus letter in the Coptic language of the monks Victor and Psan. Thebes, Byzantine Egypt, circa 580-640 Translation of a fragment of a letter into English at the Metropolitan Museum of Art website. The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Constantinople also lost access to papyrus, which was produced exclusively in Egypt, which led to an increase in the cost of books and, as a result, a decline in education. Many literary genres disappeared, the previously flourishing genre of history gave way to prophecy - having lost their cultural connection with the past, the Byzantines lost interest in their history and lived with a constant feeling of the end of the world. The Arab conquests, which caused this breakdown in the worldview, were not reflected in the literature of their time, their events are brought to us by the monuments of later eras, and the new historical consciousness reflects only an atmosphere of horror, and not facts. The cultural decline lasted for more than a hundred years, the first signs of a revival occur at the very end of the 8th century.

9. 726/730 year According to 9th-century icon-worshipping historians, Leo III issued an edict of iconoclasm in 726. But modern scientists doubt the reliability of this information: most likely, in 726, talks about the possibility of iconoclastic measures began in Byzantine society, the first real steps date back to 730.- start of iconoclastic controversy

Saint Mokios of Amphipolis and the angel killing the iconoclasts. Miniature from the Psalter of Theodore of Caesarea. 1066

Saint Mokios of Amphipolis and the angel killing the iconoclasts. Miniature from the Psalter of Theodore of Caesarea. 1066 The British Library Board, Add MS 19352, f.94r

One of the manifestations of the cultural decline of the second half of the 7th century is the rapid growth of disordered practices of icon veneration (the most zealous ones scraped and ate plaster from the icons of saints). This caused rejection among some of the clergy, who saw in this a threat of a return to paganism. Emperor Leo III the Isaurian (717-741) used this discontent to create a new consolidating ideology, taking the first iconoclastic steps in 726/730. But the most fierce disputes about icons fell on the reign of Constantine V Copronymus (741-775). He carried out the necessary military and administrative reforms, significantly strengthening the role of the professional imperial guard (tagm), and successfully contained the Bulgarian threat on the borders of the empire. The authority of both Constantine and Leo, who repelled the Arabs from the walls of Constantinople in 717-718, was very high, therefore, when in 815, after the teaching of iconodules was approved at the VII Ecumenical Council (787), a new round of war with the Bulgarians provoked a new political crisis, the imperial power returned to the iconoclastic policy.

The controversy over icons gave rise to two powerful strands of theological thought. Although the teachings of the iconoclasts are much less well known than those of their opponents, indirect evidence suggests that the thought of the iconoclasts of Emperor Constantine Copronymus and the Patriarch of Constantinople John the Grammarian (837-843) was no less deeply rooted in the Greek philosophical tradition than the thought of the iconoclast theologian John Damaskin and the head of the anti-iconoclastic monastic opposition Theodore the Studite. In parallel, the dispute developed in the ecclesiastical and political plane, the boundaries of the power of the emperor, patriarch, monasticism and episcopate were redefined.

10. 843 - The triumph of Orthodoxy

In 843, under Empress Theodora and Patriarch Methodius, the dogma of icon veneration was finally approved. It became possible thanks to mutual concessions, for example, the posthumous forgiveness of the iconoclast emperor Theophilus, whose widow was Theodora. The feast "Triumph of Orthodoxy", arranged by Theodora on this occasion, ended the era of the Ecumenical Councils and marked a new stage in the life of the Byzantine state and church. In the Orthodox tradition, he still manages to this day, and anathemas against iconoclasts, named by name, sound every year on the first Sunday of Great Lent. Since then, iconoclasm, which became the last heresy condemned by the entirety of the church, began to be mythologized in the historical memory of Byzantium.

Empress Theodora's daughters learn to read icons from their grandmother Feoktista. Miniature from the Madrid Codex "Chronicle" of John Skylitzes. XII-XIII centuries

Empress Theodora's daughters learn to read icons from their grandmother Feoktista. Miniature from the Madrid Codex "Chronicle" of John Skylitzes. XII-XIII centuries Wikimedia Commons

Back in 787, at the VII Ecumenical Council, the theory of the image was approved, according to which, in the words of Basil the Great, “the honor given to the image goes back to the prototype,” which means that worship of the icon is not an idol service. Now this theory has become the official teaching of the church - the creation and worship of sacred images from now on was not only allowed, but made a duty for a Christian. From that time on, an avalanche-like growth of artistic production began, the habitual appearance of an Eastern Christian church with iconic decoration took shape, the use of icons was integrated into liturgical practice and changed the course of worship.

In addition, the iconoclastic dispute stimulated the reading, copying and study of sources to which the opposing sides turned in search of arguments. Overcoming the cultural crisis is largely due to philological work in the preparation of church councils. And the invention of the minuscule Minuscule- writing in lowercase letters, which radically simplified and cheapened the production of books., perhaps, was due to the needs of the icon-worshipping opposition that existed under the conditions of “samizdat”: icon-worshippers had to quickly copy texts and did not have the means to create expensive uncial Uncial, or majuscule,- writing in capital letters. manuscripts.

Macedonian era

11. 863 - the beginning of the Photian schism

Dogmatic and liturgical differences gradually grew between the Roman and Eastern churches (primarily with regard to the Latin addition to the text of the Creed of the words about the procession of the Holy Spirit not only from the Father, but “and from the Son”, the so-called Filioque filioque- literally "and from the Son" (lat.).). The Patriarchate of Constantinople and the Pope fought for spheres of influence (primarily in Bulgaria, southern Italy and Sicily). The proclamation of Charlemagne as Emperor of the West in 800 dealt a severe blow to the political ideology of Byzantium: the Byzantine emperor found a rival in the person of the Carolingians.

The miraculous salvation of Constantinople by Photius with the help of the robe of the Mother of God. Fresco from the Dormition Knyaginin Monastery. Vladimir, 1648

The miraculous salvation of Constantinople by Photius with the help of the robe of the Mother of God. Fresco from the Dormition Knyaginin Monastery. Vladimir, 1648 Wikimedia Commons

Two opposing parties within the Patriarchate of Constantinople, the so-called Ignatians (supporters of Patriarch Ignatius, who was deposed in 858) and the Photians (supporters of Photius who was erected - not without scandal - instead of him), sought support in Rome. Pope Nicholas used this situation to assert the authority of the papal throne and expand his spheres of influence. In 863, he withdrew the signatures of his envoys who approved the erection of Photius, but Emperor Michael III considered that this was not enough to remove the patriarch, and in 867 Photius anathematized Pope Nicholas. In 869-870, a new council in Constantinople (to this day recognized by Catholics as the VIII Ecumenical) deposed Photius and restored Ignatius. However, after the death of Ignatius, Photius returned to the patriarchal throne for another nine years (877-886).

Formal reconciliation followed in 879-880, but the anti-Latin line laid down by Photius in the District Epistle to the episcopal thrones of the East formed the basis of a centuries-old polemical tradition, the echoes of which were heard during the rupture between the churches in, and during the discussion of the possibility of a church union in XIII and fifteenth centuries.

12. 895 - the creation of the oldest known codex of Plato

Manuscript page E. D. Clarke 39 with the writings of Plato. 895 The rewriting of the tetralogy was commissioned by Aretha of Caesarea for 21 gold coins. It is assumed that the scholia (marginal comments) were left by Aretha himself.

Manuscript page E. D. Clarke 39 with the writings of Plato. 895 The rewriting of the tetralogy was commissioned by Aretha of Caesarea for 21 gold coins. It is assumed that the scholia (marginal comments) were left by Aretha himself. At the end of the 9th century, there is a new discovery of the ancient heritage in Byzantine culture. A circle developed around Patriarch Photius, which included his disciples: Emperor Leo VI the Wise, Bishop Aref of Caesarea and other philosophers and scientists. They copied, studied and commented on the works of ancient Greek authors. The oldest and most authoritative list of Plato's writings (it is kept under the code E. D. Clarke 39 in the Bodleian Library of Oxford University) was created at this time by order of Arefa.

Among the texts that interested the scholars of the era, especially high-ranking church hierarchs, there were also pagan works. Aretha ordered copies of the works of Aristotle, Aelius Aristides, Euclid, Homer, Lucian and Marcus Aurelius, and Patriarch Photius included in his Myriobiblion "Myriobiblion"(literally "Ten thousand books") - a review of the books read by Photius, which, however, in reality were not 10 thousand, but only 279. annotations to Hellenistic novels, evaluating not their seemingly anti-Christian content, but the style and manner of writing, and at the same time creating a new terminological apparatus of literary criticism, different from that used by ancient grammarians. Leo VI himself created not only solemn speeches on church holidays, which he personally delivered (often improvising) after services, but also wrote Anacreontic poetry in the ancient Greek manner. And the nickname Wise is associated with the collection of poetic prophecies attributed to him about the fall and reconquest of Constantinople, which were remembered back in the 17th century in Rus', when the Greeks tried to persuade Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich to campaign against the Ottoman Empire.

The era of Photius and Leo VI the Wise opens the period of the Macedonian Renaissance (named after the ruling dynasty) in Byzantium, which is also known as the era of encyclopedism or the first Byzantine humanism.

13. 952 - completion of work on the treatise "On the management of the empire"

Christ blesses Emperor Constantine VII. Carved panel. 945

Christ blesses Emperor Constantine VII. Carved panel. 945

Wikimedia Commons

Under the patronage of Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (913-959), a large-scale project was implemented to codify the knowledge of the Byzantines in all areas of human life. The measure of Constantine's direct participation cannot always be determined with accuracy, however, the personal interest and literary ambitions of the emperor, who knew from childhood that he was not destined to rule, and was forced to share the throne with a co-ruler for most of his life, are beyond doubt. By order of Constantine, the official history of the 9th century was written (the so-called Successor of Theophanes), information was collected about the peoples and lands adjacent to Byzantium (“On the management of the empire”), on the geography and history of the regions of the empire (“On the themes Fema- Byzantine military-administrative district.”), about agriculture (“Geoponics”), about the organization of military campaigns and embassies, and about court ceremonial (“On the ceremonies of the Byzantine court”). At the same time, church life was regulated: the Synaxarion and the Typicon of the Great Church were created, which determined the annual order of commemoration of the saints and the holding of church services, and a few decades later (about 980), Simeon Metaphrastus began a large-scale project to unify hagiographic literature. Around the same time, a comprehensive encyclopedic dictionary of the Court was compiled, including about 30 thousand entries. But the largest encyclopedia of Constantine is an anthology of information from ancient and early Byzantine authors about all spheres of life, conventionally called "Excerpts" It is known that this encyclopedia included 53 sections. Only the section “On Embassies” has reached its full extent, and partially – “On Virtues and Vices”, “On Conspiracies against Emperors”, and “On Opinions”. Among the missing chapters: “On the peoples”, “On the succession of emperors”, “On who invented what”, “On Caesars”, “On exploits”, “On settlements”, “On hunting”, “On messages”, “ On speeches, On marriages, On victory, On defeat, On strategies, On morals, On miracles, On battles, On inscriptions, On public administration, “On Church Affairs”, “On Expression”, “On the Coronation of Emperors”, “On the Death (Deposition) of Emperors”, “On Fines”, “On Holidays”, “On Predictions”, “On Ranks”, “On the Cause of Wars ”, “On sieges”, “On fortresses”..

The nickname Porphyrogenitus was given to the children of reigning emperors, who were born in the Crimson Chamber of the Grand Palace in Constantinople. Constantine VII, son of Leo VI the Wise from his fourth marriage, was indeed born in this chamber, but formally was illegitimate. Apparently, the nickname was to emphasize his rights to the throne. His father made him his co-ruler, and after his death, the young Constantine ruled for six years under the tutelage of regents. In 919, under the pretext of protecting Constantine from the rebels, the military leader Roman I Lekapenus usurped power, he intermarried with the Macedonian dynasty, marrying his daughter to Constantine, and then was crowned co-ruler. By the time the independent reign began, Constantine had been formally considered emperor for more than 30 years, and he himself was almost 40.

14. 1018 - the conquest of the Bulgarian kingdom

Angels lay the imperial crown on Vasily II. Miniature from Basil's Psalter, Marchian Library. 11th century

Angels lay the imperial crown on Vasily II. Miniature from Basil's Psalter, Marchian Library. 11th century Ms. gr. 17 / Biblioteca Marciana

The reign of Basil II the Bulgar Slayers (976-1025) is the time of an unprecedented expansion of the church and political influence of Byzantium on neighboring countries: the so-called second (final) baptism of Russia takes place (the first, according to legend, took place in the 860s - when the princes Askold and Dir they allegedly were baptized with the boyars in Kiev, where Patriarch Photius sent a bishop specially for this); in 1018, the conquest of the Bulgarian kingdom leads to the liquidation of the autonomous Bulgarian Patriarchate, which had existed for almost 100 years, and the establishment of the semi-independent Archdiocese of Ohrid in its place; as a result of Armenian campaigns, Byzantine possessions in the East were expanding.

In domestic politics, Basil was forced to take tough measures to limit the influence of large landowning clans, who actually formed their own armies in the 970-980s during the civil wars that challenged Basil's power. He tried by harsh measures to stop the enrichment of large landowners (the so-called dinats Dinat ( from the Greek δυνατός) - strong, powerful.), in some cases even resorting to direct land confiscation. But this brought only a temporary effect, centralization in the administrative and military spheres neutralized powerful rivals, but in the long run made the empire vulnerable to new threats - the Normans, Seljuks and Pechenegs. The Macedonian dynasty, which ruled for more than a century and a half, formally ended only in 1056, but in reality, already in the 1020s and 30s, people from bureaucratic families and influential clans gained real power.

The descendants awarded Vasily with the nickname Bulgar Slayer for cruelty in the wars with the Bulgarians. For example, after winning the decisive battle near Mount Belasitsa in 1014, he ordered 14,000 captives to be blinded at once. When exactly this nickname originated is not known. It is certain that this happened before the end of the 12th century, when, according to the 13th century historian George Acropolitan, the Bulgarian Tsar Kaloyan (1197-1207) began to ravage the Byzantine cities in the Balkans, proudly calling himself a Romeo fighter and thereby opposing himself to Basil.

Crisis of the 11th century

15. 1071 - Battle of Manzikert

Battle of Manzikert. Miniature from the book "On the misfortunes of famous people" Boccaccio. 15th century

Battle of Manzikert. Miniature from the book "On the misfortunes of famous people" Boccaccio. 15th century

Bibliothèque nationale de France

The political crisis that began after the death of Basil II continued in the middle of the 11th century: clans continued to compete, dynasties constantly replaced each other - from 1028 to 1081, 11 emperors changed on the Byzantine throne, there was no such frequency even at the turn of the 7th-8th centuries . From the outside, Pechenegs and Seljuk Turks pressed on Byzantium The power of the Seljuk Turks in just a few decades in the 11th century conquered the territories of modern Iran, Iraq, Armenia, Uzbekistan and Afghanistan and became the main threat to Byzantium in the East.- the latter, having won the battle of Manzikert in 1071 Manzikert- now the small town of Malazgirt on the easternmost tip of Turkey near Lake Van., deprived the empire of most of its territories in Asia Minor. No less painful for Byzantium was the full-scale rupture of church relations with Rome in 1054, later called the Great Schism. Schism(from the Greek σχίζμα) - gap., because of which Byzantium finally lost ecclesiastical influence in Italy. However, contemporaries almost did not notice this event and did not attach due importance to it.

However, it was precisely this era of political instability, the fragility of social boundaries and, as a result, high social mobility that gave rise to the figure of Michael Psellos, unique even for Byzantium, an erudite and official who took an active part in the enthronement of emperors (his central work, Chronography, is very autobiographical) , thought about the most complex theological and philosophical issues, studied the pagan Chaldean oracles, created works in all conceivable genres - from literary criticism to hagiography. The situation of intellectual freedom gave impetus to a new typical Byzantine version of Neoplatonism: in the title of "hypata of philosophers" Ipat philosophers- in fact, the main philosopher of the empire, the head of the philosophical school in Constantinople. Psellus was replaced by John Italus, who studied not only Plato and Aristotle, but also such philosophers as Ammonius, Philopon, Porphyry and Proclus and, at least according to his opponents, taught about the transmigration of souls and the immortality of ideas.

Komnenoska revival

16. 1081 - coming to power of Alexei I Komnenos

Christ blesses Emperor Alexei I Komnenos. Miniature from "Dogmatic Panoply" by Euthymius Zigaben. 12th century

Christ blesses Emperor Alexei I Komnenos. Miniature from "Dogmatic Panoply" by Euthymius Zigaben. 12th century In 1081, as a result of a compromise with the Duc, Melissene and Palaiologoi clans, the Komnenos family came to power. It gradually monopolized all state power and, thanks to complex dynastic marriages, absorbed former rivals. Beginning with Alexios I Comnenus (1081-1118), the aristocratization of Byzantine society took place, social mobility decreased, intellectual freedoms curtailed, and imperial power actively intervened in the spiritual sphere. The beginning of this process is marked by the church-state condemnation of John Ital for "Palatonic ideas" and paganism in 1082. Then follows the condemnation of Leo of Chalcedon, who opposed the confiscation of church property to cover military needs (at that time Byzantium was at war with the Sicilian Normans and Pechenegs) and almost accused Alexei of iconoclasm. Massacres against the Bogomils take place Bogomilstvo- a doctrine that arose in the Balkans in the 10th century, in many respects ascending to the religion of the Manichaeans. According to the Bogomils, the physical world was created by Satan cast down from heaven. The human body was also his creation, but the soul is still the gift of the good God. The Bogomils did not recognize the institution of the church and often opposed the secular authorities, raising numerous uprisings., one of them, Basil, was even burned at the stake - a unique phenomenon for Byzantine practice. In 1117, the commentator of Aristotle, Eustratius of Nicaea, appears before the court on charges of heresy.

Meanwhile, contemporaries and immediate descendants remembered Alexei I rather as a ruler who was successful in his foreign policy: he managed to conclude an alliance with the crusaders and inflict a sensitive blow on the Seljuks in Asia Minor.

In the satire "Timarion" the story is told from the perspective of a hero who has traveled to the afterlife. In his story, he also mentions John Itala, who wanted to take part in the conversation of ancient Greek philosophers, but was rejected by them: “I also witnessed how Pythagoras sharply pushed away John Itala, who wanted to join this community of sages. “Scum,” he said, “having put on the Galilean robe, which they call the divine holy robes, in other words, having been baptized, you seek to communicate with us, whose life was devoted to science and knowledge? Either throw off this vulgar dress, or leave our brotherhood right now! ”” (translated by S. V. Polyakova, N. V. Felenkovskaya).

17. 1143 - coming to power of Manuel I Comnenus

The trends that emerged under Alexei I were developed under Manuel I Comnenus (1143-1180). He sought to establish personal control over the church life of the empire, sought to unify theological thought, and he himself took part in church disputes. One of the questions in which Manuel wanted to have his say was the following: what hypostases of the Trinity accept the sacrifice during the Eucharist - only God the Father or both the Son and the Holy Spirit? If the second answer is correct (and this is exactly what was decided at the council of 1156-1157), then the same Son will be both the one who is sacrificed and the one who receives it.

Manuel's foreign policy was marked by failures in the East (the most terrible was the defeat of the Byzantines at Myriokefal in 1176 at the hands of the Seljuks) and attempts at diplomatic rapprochement with the West. Manuel saw the ultimate goal of Western policy as unification with Rome based on the recognition of the supreme authority of a single Roman emperor, which Manuel himself was to become, and the unification of churches that were officially divided in. However, this project was not implemented.

In the era of Manuel, literary creativity becomes a profession, literary circles arise with their own artistic fashion, elements of the folk language penetrate into court aristocratic literature (they can be found in the works of the poet Theodore Prodrom or the chronicler Constantine Manasseh), the genre of the Byzantine love story is born, the arsenal of expressive means and the measure of the author's self-reflection is growing.

Sunset of Byzantium

18. 1204 - the fall of Constantinople at the hands of the crusaders

During the reign of Andronicus I Komnenos (1183-1185) there was a political crisis: he pursued a populist policy (reduced taxes, severed relations with the West and severely cracked down on corrupt officials), which restored a significant part of the elite against him and aggravated the foreign policy position of the empire.

Crusaders attack Constantinople. Miniature from the chronicle of the Conquest of Constantinople by Geoffroy de Villehardouin. Approximately 1330, Villardouin was one of the leaders of the campaign.

Crusaders attack Constantinople. Miniature from the chronicle of the Conquest of Constantinople by Geoffroy de Villehardouin. Approximately 1330, Villardouin was one of the leaders of the campaign. Bibliothèque nationale de France

An attempt to establish a new dynasty of Angels did not bear fruit, the society was deconsolidated. To this were added failures on the periphery of the empire: an uprising rose in Bulgaria; the crusaders captured Cyprus; Sicilian Normans ravaged Thessalonica. The struggle between pretenders to the throne within the family of Angels gave the European countries a formal reason to intervene. On April 12, 1204, members of the Fourth Crusade sacked Constantinople. We read the most vivid artistic description of these events in the "History" by Nikita Choniates and the postmodern novel "Baudolino" by Umberto Eco, who sometimes literally copies the pages of Choniates.

On the ruins of the former empire, several states arose under Venetian rule, only to a small extent inheriting Byzantine state institutions. The Latin empire, centered in Constantinople, was rather a feudal formation of the Western European type, the same character was with the duchies and kingdoms that arose in Thessalonica, Athens and the Peloponnese.

Andronicus was one of the most eccentric rulers of the empire. Nikita Choniates says that he ordered to create in one of the churches of the capital his portrait in the guise of a poor farmer in high boots and with a scythe in his hand. There were also legends about the bestial cruelty of Andronicus. He arranged public burnings of his opponents at the hippodrome, during which the executioners pushed the victim into the fire with sharp peaks, and who dared to condemn his cruelty, the reader of Hagia Sophia George Disipat threatened to roast on a spit and send to his wife instead of food.

19. 1261 - the reconquest of Constantinople

The loss of Constantinople led to the emergence of three Greek states that equally claimed to be the full heirs of Byzantium: the Nicaean Empire in northwestern Asia Minor under the rule of the Laskar dynasty; The Empire of Trebizond in the northeastern part of the Black Sea coast of Asia Minor, where the descendants of the Komnenos settled - the Great Komnenos, who took the title of "emperors of the Romans", and the Kingdom of Epirus in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula with the dynasty of Angels. The revival of the Byzantine Empire in 1261 took place on the basis of the Nicaean Empire, which pushed aside competitors and skillfully used the help of the German emperor and the Genoese in the fight against the Venetians. As a result, the Latin emperor and patriarch fled, and Michael VIII Palaiologos occupied Constantinople, was re-crowned and proclaimed "the new Constantine."

In his policy, the founder of the new dynasty tried to reach a compromise with the Western powers, and in 1274 he even agreed to a church union with Rome, which set the Greek episcopate and the Constantinopolitan elite against him.

Despite the fact that the empire was formally revived, its culture lost its former “constantinopolecentricity”: the Palaiologians were forced to put up with the presence of the Venetians in the Balkans and the significant autonomy of Trebizond, whose rulers formally renounced the title of “Roman emperors”, but in reality did not leave imperial ambitions.

A vivid example of the imperial ambitions of Trebizond is the Cathedral of Hagia Sophia of the Wisdom of God, built there in the middle of the 13th century and still making a strong impression today. This temple simultaneously contrasted Trebizond with Constantinople with its Hagia Sophia, and at the symbolic level turned Trebizond into a new Constantinople.

20. 1351 - approval of the teachings of Gregory Palamas

Saint Gregory Palamas. Icon of the master of Northern Greece. Early 15th century

Saint Gregory Palamas. Icon of the master of Northern Greece. Early 15th century

The second quarter of the 14th century saw the beginning of the Palamite controversy. St. Gregory Palamas (1296-1357) was an original thinker who developed the controversial doctrine of the difference in God between the divine essence (with which a person can neither unite nor know it) and the uncreated divine energies (with which connection is possible) and defended the possibility contemplation through the "intelligent feeling" of the Divine light, revealed, according to the Gospels, to the apostles during the transfiguration of Christ For example, in the Gospel of Matthew, this light is described as follows: “After six days, Jesus took Peter, James and John, his brother, and brought them up to a high mountain alone, and was transformed before them: and His face shone like the sun, and his clothes They became as white as the light” (Matt. 17:1-2)..

In the 40s and 50s of the XIV century, the theological dispute was closely intertwined with political confrontation: Palamas, his supporters (Patriarchs Kallistos I and Philotheus Kokkinos, Emperor John VI Kantakuzen) and opponents (later converted to Catholicism, the philosopher Barlaam of Calabria and his followers Gregory Akindin, Patriarch John IV Kalek, philosopher and writer Nicephorus Gregory) alternately won tactical victories, then suffered defeat.

The Council of 1351, which approved the victory of Palamas, nevertheless did not put an end to the dispute, the echoes of which were heard in the 15th century, but forever closed the way for the anti-Palamites to the highest church and state power. Some researchers following Igor Medvedev I. P. Medvedev. Byzantine humanism of the XIV-XV centuries. SPb., 1997. they see in the thought of the anti-Palamites, especially Nikifor Grigora, tendencies close to the ideas of the Italian humanists. Humanistic ideas were even more fully reflected in the work of the Neoplatonist and ideologist of the pagan renewal of Byzantium, Georgy Gemist Plifon, whose works were destroyed by the official church.

Even in serious scholarly literature one can sometimes see that the words "(anti)palamites" and "(anti)hesychasts" are used interchangeably. This is not entirely true. Hesychasm (from the Greek ἡσυχία [hesychia] - silence) as a hermit prayer practice, which makes it possible to directly experience communication with God, was substantiated in the works of theologians of earlier eras, for example, Simeon the New Theologian in the X-XI centuries.

21. 1439 - Ferrara-Florence Union

Union of Florence by Pope Eugene IV. 1439 Compiled in two languages - Latin and Greek.

Union of Florence by Pope Eugene IV. 1439 Compiled in two languages - Latin and Greek. British Library Board/Bridgeman Images/Fotodom

By the beginning of the 15th century, it became clear that the Ottoman military threat called into question the very existence of the empire. Byzantine diplomacy actively sought support in the West, negotiations were underway on the unification of churches in exchange for military assistance from Rome. In the 1430s, a fundamental decision on unification was made, but the venue of the cathedral (on Byzantine or Italian territory) and its status (whether it would be designated as “unifying” in advance) became the subject of bargaining. In the end, the meetings took place in Italy - first in Ferrara, then in Florence and in Rome. In June 1439, the Ferrara-Florence Union was signed. This meant that formally the Byzantine Church recognized the correctness of the Catholics on all controversial issues, including the issue. But the union did not find support from the Byzantine episcopate (Bishop Mark Eugenicus became the head of its opponents), which led to the coexistence in Constantinople of two parallel hierarchies - Uniate and Orthodox. 14 years later, immediately after the fall of Constantinople, the Ottomans decided to rely on the anti-Uniates and installed a follower of Mark Eugenicus, Gennady Scholarius, as patriarch, but formally the union was abolished only in 1484.

If in the history of the church the union remained only a short-lived failed experiment, then its trace in the history of culture is much more significant. Figures like Bessarion of Nicaea, a disciple of the neo-pagan Plethon, a Uniate metropolitan, and then a cardinal and titular Latin patriarch of Constantinople, played a key role in the transmission of Byzantine (and ancient) culture to the West. Vissarion, whose epitaph contains the words: “Through your labors, Greece moved to Rome,” translated Greek classical authors into Latin, patronized Greek emigrant intellectuals, and donated his library to Venice, which included more than 700 manuscripts (at that time the most extensive private library in Europe), which became the basis of the Library of St. Mark.

The Ottoman state (named after the first ruler Osman I) arose in 1299 on the ruins of the Seljuk Sultanate in Anatolia and during the 14th century increased its expansion in Asia Minor and the Balkans. A brief respite for Byzantium was given by the confrontation between the Ottomans and the troops of Tamerlane at the turn of the 14th-15th centuries, but with the coming to power of Mehmed I in 1413, the Ottomans again began to threaten Constantinople.

22. 1453 - the fall of the Byzantine Empire

Sultan Mehmed II the Conqueror. Painting by Gentile Bellini. 1480

Sultan Mehmed II the Conqueror. Painting by Gentile Bellini. 1480

Wikimedia Commons

The last Byzantine emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos, made unsuccessful attempts to repel the Ottoman threat. By the early 1450s, Byzantium retained only a small region in the vicinity of Constantinople (Trapezund was actually independent from Constantinople), and the Ottomans controlled both most of Anatolia and the Balkans (Thessalonica fell in 1430, Peloponnese was devastated in 1446). In search of allies, the emperor turned to Venice, Aragon, Dubrovnik, Hungary, the Genoese, the Pope, but real help (and very limited) was offered only by the Venetians and Rome. In the spring of 1453, the battle for the city began, on May 29 Constantinople fell, and Constantine XI died in battle. About his death, the circumstances of which are not known to scientists, many incredible stories were composed; in Greek folk culture for many centuries there was a legend that the last Byzantine king was turned into marble by an angel and now rests in a secret cave at the Golden Gate, but is about to wake up and drive out the Ottomans.

Sultan Mehmed II the Conqueror did not break the line of succession with Byzantium, but inherited the title of Roman Emperor, supported the Greek Church, and stimulated the development of Greek culture. The time of his reign is marked by projects that at first glance seem fantastic. The Greek-Italian Catholic humanist George of Trebizond wrote about building a world empire led by Mehmed, in which Islam and Christianity would unite into one religion. And the historian Mikhail Kritovul created a story in praise of Mehmed - a typical Byzantine panegyric with all the obligatory rhetoric, but in honor of the Muslim ruler, who, nevertheless, was not called the sultan, but in the Byzantine manner - the basil.

Around the end of the 12th century. Byzantium was experiencing a period of rise in its power and influence in the world. After that, the era of its decline began, which progressed, which ended with the complete collapse of the empire and its disappearance forever from the political map of the world in the middle of the 15th century. It is unlikely that anyone could have predicted such an end to the brilliant state at the beginning of the 11th century, when the Macedonian dynasty was in power. In 1081 she was replaced on the throne by a no less imposing dynasty of emperors from the Komnenos family, which remained ruling until 1118.

Byzantium was considered one of the most powerful and wealthy states in the world, its possessions covered a vast territory - about 1 million square meters. km with a population of 20-24 million people. The capital of the state, Constantinople, with its millionth population, majestic buildings, countless treasures for the European peoples, was the center of the entire civilized world. The gold coin of the Byzantine emperors - the bezant - remained the universal currency of the Middle Ages. The Byzantines considered themselves the main custodians of the cultural heritage of antiquity and at the same time the stronghold of Christianity. No wonder the sacred writings of Christians around the world - the Gospels - were also written in Greek.

The growing power of the Byzantine Empire was reflected in an active foreign policy, which rested on military achievements as much as on the missionary activities of the church. According to the revived ideology of Byzantine ecumenism, the empire retained historical and legal rights to all territories that were once part of it or were dependent on it. The return of these lands was considered a priority of Byzantine foreign policy. The troops of the empire won one victory after another, adding to it new provinces in the Middle East, southern Italy, Transcaucasia, and the Balkans. The Byzantine navy, equipped with "Greek fire", drove the Arabs out of the Mediterranean.

The missionary activity of the Orthodox Church acquired an unprecedented scope before. its main destinations were the Balkans, Eastern and Central Europe. In a fierce competition with Rome, Byzantium managed to win in Bulgaria, including it in the orbit of Byzantine culture and politics. A huge success of imperial foreign policy was the Christianization of Rus'. Byzantine influences became more and more tangible in the territory of Moravia and Pannonia.

Until the 20th century. the classical Byzantine model of civilization finally took shape with all the features of its state, socio-economic and cultural life, which fundamentally distinguished it from Western Europe. The most characteristic feature of Byzantium was the omnipotence of a centralized state in the form of an unlimited autocratic monarchy. At its center was the emperor, who was considered the only legitimate heir to the Roman rulers, the father of a great family of all peoples and states that belonged to the sphere of influence of Byzantium. The all-pervading control of a rigidly centralized state machine over society, its petty regulation and constant guardianship would be impossible without a powerful caste of state officials. This model had a clear hierarchy of positions and titles, consisting of 18 classes and 5 categories - a kind of "Table of Ranks". The faceless army of bureaucrats in the center and locally carried out fiscal, administrative, judicial and police functions with zeal and perseverance, which for the population turned into an ever-growing burden of taxes and duties, the flourishing of corruption and servility. Public service provided a person with an honorable place in society, became the main source of its income.

The church was an extremely important component of Byzantine statehood. It ensured the spiritual unity of the country, educated the population in the spirit of imperial patriotism, and played a colossal role in the foreign policy of Byzantium. In the X-XI centuries. the number of monasteries and monks continued to grow, as well as church and monastic land ownership. Although, according to the Byzantine tradition, the church was subordinated to the authority of the emperor, its role in the socio-political and cultural life was constantly growing. To the extent that the power of the emperors weakened, the church became the main bearer of the doctrine of Byzantine ecumenism.

at the same time, in Byzantium, unlike the countries of the West, a civil society with its inherent corporate ties and institutions, a developed system of private property, did not form. The personality there seemed to be one on one with the emperor and God. Such a social system has received in modern historiography the apt name of individualism without freedom.

A characteristic feature of the socio-economic development of Byzantium in the IX-XV centuries. can be considered the dominance of the village over the city. Unlike Western Europe, in Byzantium, feudal relations in the countryside developed very slowly. Private ownership of land remained extremely weak. The long existence of the peasant community, the widespread use of slave labor, state control and tax pressure determined the nature of social development in the countryside. However, over time, large landed estates arose that belonged to secular and church owners. They became the main centers of handicraft production and trade.

The progressive degradation of the city turned out to be another feature of the socio-economic development of Byzantium. In contrast to Western Europe, the city did not become the main center and factor of progress there. Byzantine cities had almost nothing in common with the ancient ones. They rather resembled large villages in appearance, monotonous architecture, primitive amenities, close ties of their inhabitants with agriculture. Traditions of a special urban culture, self-government, awareness of their own municipal interests with their inherent rights and obligations of residents have not been formed in the country. The city was under the strict control of the state. In the Byzantine cities, corporate professional associations of artisans and merchants did not take shape according to the guild model. In the last decades of the existence of the empire, its cities actually turned into an annex to rural crafts and trade, developed in feudal estates.

One of the consequences of the decline of the Byzantine city was the degradation of trade. Byzantine merchants gradually lost their capital and influence in society. The state did not protect their interests. The main monetary income of the social elite was brought not by trade, but by public service and land ownership. Therefore, almost all of the external and internal trade of Byzantium eventually passed into the hands of the Venetian and Genoese merchants.