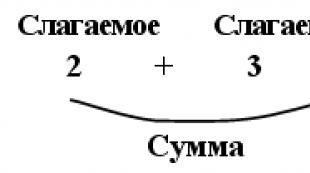

Revolutions in Europe (1848-1849). Revolutions in Europe (1848-1849) Revolutions in 1848 1849

Causes of revolutions. In the second half of the XIX century. there was a general deterioration in the economic situation in Europe. Two years in a row 1845-1847 were lean (with respect to potatoes and cereals, the main food products of the population). A direct consequence of poor harvests was the rapid rise in food prices. In a number of European countries, famine began, aggravated by diseases (epidemics of typhoid and cholera). In some areas, deaths from starvation have been recorded, with hundreds of people dying. A wave of hunger riots swept across Europe, when people smashed bread shops, lynched speculators. The authorities often suppressed popular uprisings with the help of troops.

In 1847, a trade and economic crisis began in England, which quickly spread throughout Europe and became a pan-European one. Its consequences were a reduction in production, a massive ruin of small and medium-sized owners, and a rapid rise in unemployment. In large cities, the workers staged riots and revolts, demanding an improvement in the situation. Among the population, dissatisfaction was ripening with the deteriorating economic situation in Europe, as well as the inability of the government to fight to improve the people's condition and economy. Most European governments brutally suppressed popular uprisings, believing that this would restore order in the country.

In addition to the sharp deterioration of the economic situation in 1845-1848, there were other reasons for the revolutions of 1848-1849. In many countries, feudal vestiges remained, which created barriers to the development of capitalist relations. This gave rise to conflicts and contradictions, which led to the revolution.

By the middle of the XIX century. the economy of large European countries entered a higher level of its development: the transition from manufacturing to industrial stage of industry began. The industrial revolution swept over all new countries. If in England the industrial revolution was practically completed, in France it was gaining momentum, then in Germany and Austria the industrial revolution had just begun. Under his direct influence, changes took place in the social sphere - to the strengthening of the bourgeoisie and the growth of the proletariat.

Everywhere, except for France and England, the feudal-absolutist order was preserved. This is how feudal land ownership, guild system, noble privileges were preserved, there were restrictions in customs and tax policies. In Germany, this was added to the political and economic disunity, the lack of uniform measures and weights. In Italy, there was political fragmentation, the dependence of a number of states on the Austrian Empire, in Austria the economic and political domination of large landowners flourished, customs policies were carried out in the interests of a narrow social circle and national oppression of non-indigenous peoples. Feudal vestiges in European countries hampered the general European development of capitalism, since they hindered the formation of a common market for Europe.

The monarchs and sovereigns of Europe tried to preserve the old order in both politics and economics. So especially for this in 1815, the "Holy Union" was created, the purpose of which was to maintain calm in Europe and prevent revolutionary uprisings. For the successful development of capitalism, the elimination of feudal remnants was necessary.

By the middle of the 19th century, after the Napoleonic wars, the feudal system began to decline, as it had to adapt to new economic conditions. So in a number of German states during the Napoleonic wars, serfdom (the release of peasants for ransom) was abolished, the guild system was abolished. In 1818 in Prussia, internal customs were destroyed, in the 30s. under her leadership, 18 German states united in the Customs Union, which contributed to the development of German industry. At the same time, Austria provided a number of benefits to the off-shop industry. The feudal system could adapt to new conditions; all that was needed was an incentive to modernize it.

Despite the development of capitalism and the strengthening of the economic role, the bourgeoisie could not exert political influence on the domestic and foreign policies of their states. The bourgeoisie strove to achieve an increase in its status, an increase in power and influence in the state. She demanded economic and political freedoms, but given the preservation of absolutism, this was impossible.

Since the 20s. XIX century. Oppositional ideas in the form of liberal theories are widely spread among the bourgeoisie. In France, the works of Benjamin Constant are popular, who called the bourgeoisie, not the nobility, the main support of society, and demanded the inviolability of private property, freedom of conscience and individual rights. The philosophical teachings of Schelling and Hegel are popular in Germany.

The July Revolution of 1830 in France established a bourgeois constitutional monarchy. In 1832, a parliamentary reform was carried out in England, as a result of which the British bourgeoisie was able to participate in political decisions. In Austria, in the circles of the bourgeois intelligentsia, the possibility of introducing democratic freedoms was discussed. In the Italian states, the movement for the national liberation of the country and the democratization of political life spread.

All these numerous projects boiled down to two main political demands: "freedom and a constitution", which became the general slogans of the European bourgeoisie on the eve and during the revolutions of 1848-49. The meaning of these requirements was to change the form of government, to create constitutional regimes in the form of bourgeois monarchies or bourgeois republics, depending on national conditions. But practically all the leaders of the bourgeois opposition opposed the revolution, fearing a bloody massacre and popular revolt.

In parallel with the strengthening of the bourgeoisie, there was an increase and strengthening of the working class. In those countries where the industrial revolution took place. The workers begin to demand an improvement in their situation, the first workers' trade unions are formed, and the strike movement develops. The results of the increase in the social and political activity of the working class in the first half of the nineteenth century. became the Chartist movement in England, the Lyon weavers uprisings in 1831 and 1834. in France, the uprising of Silesian weavers in 1844 in Germany. In most cases, the workers put forward only economic demands, seeking higher wages or shorter working hours. But gradually political demands began to appear. Socialist doctrines were of greater importance to the workers. In the 30-40s of the XIX century. in France, a doctrine called "socialism" became very popular among workers. Its ideologues propagated among the workers various means to improve their situation - from moderate reforms to class war and popular uprising. What they had in common was that they called for the establishment of "social justice", that is, for an equal distribution of social wealth among all classes of society. There were both utopian ideas (E. Cabet about complete equality and the absence of private property), as well as more realistic ideas of the transformation of society by Louis Blanc. The universal right to work, society must about the exercise of this right. The state should assist in the creation of "public workshops" in the main branches of industry, that is, of the type of cooperatives, which would gradually become completely the property of the workers. Since labor in these workshops will be much more productive than forced labor in private enterprises, the latter will go bankrupt and give way to workers' enterprises. In the course of time, the entire industry will pass into the hands of the workers, thereby achieving social justice and general harmony.

Thus, by the middle of the XIX century. In the midst of the European bourgeoisie and the working class, ideas and demands for changes in social life were formed. Although the political demands and slogans of "freedom and a constitution" coincided among the workers and the bourgeoisie. But the leaders of the workers put their own meaning, for them freedom and a constitution were needed as a means of changing their socio-economic position. But the demands for a "right to work" and a "social republic", which found support among the workers, aroused the discontent of the bourgeoisie.

As a result, on the eve of the revolutions of 1848-49. the workers and the bourgeoisie acted simultaneously as allies and opponents. Allies - in the struggle for democracy and freedom against feudal remnants, opponents - in relation to the existing socio-economic system and property. During the course of the revolution, this duality manifested itself in the different understanding of its goals and in the conflicts between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat.

One of the reasons for the revolutions of 1848-49. national problems became, and in all countries except France, revolutions were largely the result of the rise of national movements.

By the middle of the XIX century. many of the peoples of Europe were ruled by foreign monarchs. The situation was aggravated by the fact that they were subjected to national oppression by the ruling nation, as was the case, for example, in the Austrian Empire. More than half of its 34 million people were Slavic peoples: Czechs, Poles, Croats, Slovenes and others. The empire also included the Kingdom of Hungary and the two Italian regions of Lombardy and Venice, whose population in total reached 10 million. All of them were deprived of political rights and the opportunity to develop their own culture. Only Hungary had relative independence; the rest of the national areas were provinces of the Habsburg Empire. Austrian Germans held all government offices; only German was used in schools, courts, institutions; the government pursued a policy of Germanization and persecuted all manifestations of national identity.

A similar situation developed in Prussia, where the Germans limited the rights of the local Slavs. The Hungarians, dissatisfied with the domination of the Austrians, themselves oppressed the Croats and Serbs who lived in the southern districts of Hungary. But the worst was the position of the Poles, who, as a result of numerous partitions of Poland, were divided between Russia (Kingdom of Poland), Prussia (Duchy of Poznan) and Austria (Western Galicia).

Inequality and national oppression caused growing discontent and resistance, which took various forms: from the desire for national liberation to nationalism; from moderate enlightenment to the creation of secret conspiratorial organizations and uprisings.

Patriotic ideas were gaining strength everywhere. In the Slavic lands of the Austrian Empire, literary and historical works were spread that described the life and traditions of the Slavs, thereby contributing to the growth of national identity. On the eve of the revolution, the "Slavic revival" began to take on a political character, expressed in the requirements for the creation of national schools, the development of national culture, as well as self-government and autonomy. In Hungary, the National Assembly took up the development of measures for the development of Hungarian industry, the creation of the National Bank and its own Academy of Sciences. The Poles and Italians were even more determined. In 1830-31. in the Kingdom of Poland, under the slogan of national liberation, an uprising broke out, brutally suppressed by Nicholas I. In the early 1940s, members of patriotic organizations began to prepare for a new all-Polish uprising. It began in Krakow in February 1846, but was also suppressed by the joint efforts of the Prussian, Austrian and Russian troops. Numerous secret societies were active throughout Italy, which repeatedly revolted against Austrian oppression.

The leaders of the national liberation movement were representatives of the local noble aristocracy and intelligentsia. They were encouraged to participate in the struggle both by noble patriotic feelings and political calculation. The Polish, Hungarian, Czech nobility sought to revive the former power of their countries and peoples, and at the same time - their own power over them.

National slogans also found sympathy in the bourgeois environment, since the movement towards national liberation was caused not only by ethnic and cultural, but also by socio-economic factors. In the first half of the XIX century. the small nations of Europe successfully developed their own industry and trade, as, for example, in the Czech Republic, which by the middle of the century had become one of the most economically developed regions of the Austrian Empire. There was a process of formation of a national bourgeoisie, for which independence meant the ability to independently manage economic resources in their regions. For this reason, representatives of the bourgeoisie took the most active part in the national liberation movement.

The bourgeoisie also had its own political goals - the same as those of the bourgeoisie of other European countries. They consisted in the implementation of liberal reforms and participation in public administration. And here her interests and the interests of the nobility diverged significantly. If the nobility wanted to preserve and strengthen the old feudal order, the bourgeoisie sought to change them.

As a result, the struggle for national liberation merged with revolutionary movements, and the demands for revolutionary change were reinforced by national sentiment.

The desire for national self-determination was expressed in other forms as well. Some of the peoples of Europe, although they were not oppressed, were also deprived of the opportunity to determine their own destiny, since they did not have their own statehood. Such was the situation in Germany and Italy, where there was no centralized state and the remnants of political fragmentation remained.

34 German states united in the German Confederation - a confederation, whose members were absolutely independent in dealing with internal and partly external affairs.

Italy's political fragmentation was exacerbated by its national humiliation. Of the eight Italian states located on the Apennine Peninsula, only the Kingdom of Sardinia retained its independence. Lombardy and Venice were part of the Austrian Empire. In the duchies of Tuscany and Modena, the throne was occupied by sovereigns from the house of the Habsburgs, and Parma belonged to the ex-wife of Napoleon I, Marie-Louise. Here the Austrians organized the army and the police, looked through the correspondence, and persecuted the opposition. Austria had the right to keep its garrisons in several fortresses of the Papal State and to interfere in the internal affairs of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

In addition to the fact that the political fragmentation of Germany and Italy became a serious obstacle to their further development. It hindered the formation of a single national market, the widespread introduction of capitalist relations, and thereby perpetuated economic backwardness. Because of it, the international influence of these countries in European affairs was weakened. Finally, political fragmentation came into conflict with the formation of a single nation and the growth of national self-awareness.

Therefore, the elimination of political fragmentation and the creation of a single national state was one of the pressing historical tasks facing the Germans and Italians. At the same time, if the Germans had to overcome their own disunity, then in Italy the path to unification lay through the achievement of national independence.

Thus, in Italy, Germany, Hungary, in the Slavic lands of the Austrian Empire - wherever the question of national independence and state sovereignty arose, any social, and even more so revolutionary, movement inevitably acquired a national character and used national slogans. In turn, the goals of the national liberation movement became one of the most important tasks of the revolution in these countries.

Based on the ratio of general tasks and national characteristics of the revolutions of 1848-49. they can be divided into three types.

Of all the countries where revolutions took place, France was the most developed economically and politically. The feudal system was destroyed here in the 18th century, and the development of capitalism reached high level... In France there was a fairly organized labor movement, and the conflict between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie was already evident. Therefore, the main task of the revolution was the elimination of the domination of the financial oligarchy that ruled France during the July monarchy, the democratization of political life and the creation of more favorable conditions for the further development of capitalism.

Revolutions in the Austrian Empire and Italy, economically weak countries with insignificant elements of capitalism, can be defined as a struggle against feudal remnants. As in the early bourgeois revolutions of the 17th-18th centuries, their goal was to destroy the foundations of the feudal order, destroy the absolutist system and clear the way for the development of bourgeois relations. New historical conditions manifested themselves in the participation of a small number of workers' representatives in the revolutionary movement and in their own economic demands.

Both in Italy and in the Austrian Empire, the national question had a significant impact on the development of the revolutionary movement. But the nature and results of this influence were different. Hatred of Austrian oppression united all Italians, and patriotic feelings were a factor that strengthened the revolutionary movement. In the Austrian Empire, on the contrary, interethnic contradictions became one of the reasons for the defeat of the revolution. For the sake of their own liberation, some peoples, themselves oppressed by the Habsburgs, were ready to help the Austrians in suppressing the revolutionary movement in their neighbors. At all its stages, the successes and failures of the Austrian revolution depended on the complex interaction of the revolutionary movement in Austria itself and in the national outskirts of the empire.

According to its typological characteristics, the revolution in Germany occupied an intermediate position between the revolutions in France, on the one hand, and in the Austrian Empire and Italy, on the other. In economic and political development, the countries of the German Confederation were significantly inferior to France and they still had a significant way to go in the direction of bourgeois society. At the same time, capitalist relations developed intensively in certain regions of Germany and many elements of the feudal system were eliminated. Thus, the goal of the revolution in Germany was to eliminate feudal remnants and bring to an end the bourgeois coup d'etat begun as a result of the reforms.

The political isolation of the German states left its mark on the course of the German revolution. Each of the German states had its own revolution, although, ultimately, the fate of all of them depended on the development of events in the largest states of the German Confederation - Prussia and Austria. At the same time, the desire to create a unified German state gave rise to attempts to unite the efforts of all participants in the revolution, which was reflected in the activities of the all-German parliament.

Revolution in France.

Reasons and course. Due to potato disease and low grain yields, food prices have skyrocketed. Added to this were the economic and financial crises. In France, in 1847, production began to decline in all spinning and weaving mills. Meanwhile, a crisis in railway construction was brewing due to speculation in company shares. A French bank, buying foreign bread, paid in gold. The gold reserves of the Bank of France in 1845 fell from 320 million francs. up to 47 million in January 1847 The French bank owes its salvation from bankruptcy to Nicholas I, who bought fr. an annuity of 50 million francs. In 1847 the bankruptcy of enterprises began. The situation of all segments of the population has deteriorated. Broad sections of the bourgeoisie were dissatisfied with the domestic and foreign policies of Louis Philippe. They sought to expand the electoral system, fight against corruption in the state apparatus, change customs policy and other reforms.

After the defeat in parliament, the liberal opposition resumed banquets against the Guizot government. The initiative of the campaign belonged to the "dynastic opposition" party led by O. Barro. A new banquet of supporters of electoral reform in Paris was scheduled for January 19, but due to the ban of the authorities postponed to February 22. It was to be accompanied by a street demonstration in defense of freedom of assembly. The authorities banned the banquet and demonstration. On the evening of February 21, the opposition called on the people to submit to the authorities.

But the people, led by students and workers from the suburbs, took to the streets on February 22. The troops began to disperse the crowd. The first barricades began to appear. The next day, clashes and clashes between the demonstrators and the troops and police intensified.

The Parisian National Guard, made up of the middle and petty bourgeoisie, sympathized with the demonstrators, supporting the slogans. "Long live the reform!", "Down with Guizot!" By the end of the day on February 23, Louis-Philippe is forced to resign Guizot. The head of the new government was appointed Count Molay, who enjoyed a reputation as a liberal Orleanist. The bourgeoisie supported the appointment and wanted to end the struggle. The slogans began to be heard "Down with Louis Philippe!"

On the evening of February 23, a column of demonstrators heading for the building of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, where Guizot lived, was shot by the troops guarding the building. There were killed and wounded. This incident raised popular indignation. Over 1,500 barricades were built overnight. The uprising became widespread. The leadership of the uprising was taken by left-wing republicans and members of secret revolutionary societies. On the morning of February 24, many national guards joined the uprising, the rebels seized weapons depots and barracks. The slogans began to be heard "Down with Louis Philippe!" "Long live the republic!" The king tried to change the situation, he appointed the leader of the dynastic opposition O. Barro as head of government, but this did not bring success.

At noon on the 24th, the royal palace was captured, and Louis-Philippe abdicated the throne and fled Paris. In the Chamber of Deputies, the majority tried to save the monarchy. But the rebels broke into the meeting room and demanded the proclamation of a republic. Under pressure from the workers, it was decided to elect a Provisional Government. The majority in the government belonged to the liberals. The elderly Dupont de L'Er was elected chairman. The actual head of government was Lamartine, who took over as foreign minister. The ministers opposed an immediate decision on the proclamation of a republic.

On the morning of February 25, the Provisional Government proclaimed France a republic. On February 25, under pressure from the workers, the government issued a decree proclaiming its commitment to "provide jobs for all citizens" and recognizing the right of workers to form workers' unions. The demonstration of workers' corporations demanded the creation of a "ministry of labor and progress" and the "abolition of the exploitation of man by man."

The Provisional Government made a compromise by creating a "government commission for workers." The task of which is "to discuss and develop measures to improve the position of the working class." Louis Blanc and Albert were appointed its chairman and deputy, and the Luxembourg Palace was assigned to her work. Hence its name - the Luxembourg Commission, but it received neither real power nor money, it became a "ministry of good wishes."

In the following days, the government adopted decrees to reduce the working time by 1 hour (to 10 hours in Paris and to 11 hours in the provinces), to reduce the price of bread, to provide workers' associations with a million francs left over from the former king, and to return from pawnshops to the poor. pledged essentials, the abolition of class restrictions for joining the National Guard. On March 4, a decree was proclaimed introducing universal suffrage in France for men who have reached the age of 21 (with a 6-month residence in the area).

On February 25 and 26, decrees were issued on the creation in Paris of a volunteer "mobile national guard" of 24 thousand people. On February 26, it was announced the creation of public works for the unemployed in Paris, i.e. "National workshops". This was a measure to ease social tensions in the capital and strengthen confidence in the Provisional Government.

But the revolution did not solve financial issues. It gave rise to the stock exchange, banking and monetary panic, exacerbated the economic crisis. Industrialists closed their businesses, i.e. fought the demands of the workers by artificially increasing unemployment. Public finances fell into disrepair. Many banks have gone bankrupt. The bankruptcy threat looms over the Bank of France. The interim government, in search of a way out of the crisis, went to increase taxes on small owners. On March 17, it was decided to increase by one year by 45% all direct taxes falling on landowners. The new 45-centimeters tax (each franc of the old taxes was increased by 45 centimes) fell its burden mainly on the peasants.

The Provisional Government has scheduled elections for the Constituent Assembly for April 9th. But this was opposed by the workers at the demonstrations, demanding a postponement. The government has postponed the elections until April 23.

On April 23rd and 24th, elections to the Constituent Assembly took place in France. All the male population over 21 took part in them. In total, 880 deputies were elected to the Constituent Assembly. Most of them - about 500 - in their views were close to the moderate wing of the Provisional Government, that is, the political democrats. They supported a liberal democratic republic. About 300 members of the Constituent Assembly called themselves Conservatives. In fact, they belonged to various monarchist groupings, mainly Orleanists. The Socialists did not even recruit 30 people. The Constituent Assembly (legislative branch) organized an Executive Commission, modeled on the Constitution of 1795, to represent the executive branch. The commission consisted of five people who were led by ministers responsible for individual branches of government.

On May 15, the democrats and socialists, dissatisfied with the composition of the new government, took 150 thousand people to the streets of Paris. A group of demonstrators burst into the meeting room of the Constituent Assembly and tried to form their own government by declaring the Constituent Assembly dissolved. While the revolutionaries were discussing the composition of the new government, the Executive Commission ordered the National Guard to suppress the rebellion. The soldiers occupied the town hall. The revolutionary leaders were arrested. Then the democratic clubs were closed.

These events led to a sharp demarcation of political forces. The by-elections to the Constituent Assembly, held on June 4, were won mainly by representatives of the extreme parties, including monarchists and socialists. Prince Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, nephew of Napoleon I and a contender for the imperial throne, was elected deputy. On June 21, the Executive Commission passed a decree that provided for the dissolution of the "national workshops", but at the same time allowed workers between the ages of 18 and 25 to join the army, and the rest to go to drain the marshes in the province. The payment of the allowance was terminated. The very next day, unrest began among the workers. On June 23, a large rally took place on the Place de la Bastille, the participants of which with the words "Freedom or death!" began to build barricades. The uprising was spontaneous. The insurgents had neither a plan of action nor general leadership. All revolutionary leaders have been in prison since May 15. The government fought against the insurgents under the slogan of protecting the Republic, order and legality against anarchy. On June 24, the Executive Commission resigned. The Constituent Assembly, having declared Paris under a state of siege, handed over executive power to the Minister of War General Caveniak. On the morning of June 25, the army, supported by the National Guard, launched an offensive against the rebels. By the morning On June 26, their resistance was finally broken. The capture of the last barricades by the troops was accompanied by the execution of the rebels without trial or investigation. In total, about 11 thousand people died during the uprising. Human. About 15 thousand people were detained by the forces of order and thrown into prisons. On June 28, General Cavaignac formed a cabinet of ministers, which consisted mainly of moderate Republicans. They proposed measures aimed at restricting the rights and freedoms of citizens. The Constituent Assembly passed a law that effectively put democratic clubs under the control of the authorities. Another law limited freedom of the press by setting large bail bonds for newspaper publishers. A special commission to investigate the events of May 15 and June 23 demanded that the Socialists be brought to trial. In early July, "national workshops" were disbanded throughout the country, and in September the working day was again increased to 12 hours. In the summer of 1848, a special commission prepared a draft of a new constitution. On September 4, the draft was submitted for discussion by the Constituent Assembly, and two months later, on November 4, it was put to a vote, and the constitution was adopted by a majority of votes (739 against 30). The Constitution established in France a "single and indivisible" republic, the principles of which were freedom, equality and brotherhood, and the foundations were family, labor, property and public order. She endowed citizens with broad democratic rights and freedoms. However, instead of "the right to work", it spoke only of the need for "fraternal assistance to citizens in need." The constitution prescribed the principle of separation of powers. The supreme legislative power was vested in a unicameral Legislative Assembly, and the highest executive - the president republics, which was a new phenomenon for France. The members of the assembly were elected on the basis of universal suffrage. Deputies , supported the idea of a nationwide election of the president. The Constituent Assembly set the presidential elections for December 10, 1848. The main contenders were Cavaignac, Lamartine, Ledru-Rollin, and also Prince Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte. Bonaparte won with ¾ of the number of voters who took part in the voting.

The main gains of the revolution were: the proclamation of the republic, the democratization of the electoral system, the creation of government commissions to resolve the labor issue, the reduction of the working day.

Revolution in Germany. The general deterioration of the situation intensified the opposition among the bourgeoisie and other strata of the population, striving to destroy the feudal-absolutist order and liquidate political fragmentation. News of the revolution in France reached Germany on February 26 and served as a signal for revolutionary uprisings. They began on 27 February in the Duchy of Baden. On March 1, under pressure from a large protest demonstration, the government resigned 3 reactionary ministers, replacing them with more liberal ones. Other demands of the opposition were also fulfilled: censorship was abolished, the creation of a civil army was allowed, and the convocation of a representative assembly was promised. On March 2, revolutionary demonstrations took place in the Kingdom of Württemberg and Bavaria. In Bavaria, the workers and students of Munich erected barricades and demanded the removal of the reactionary ministers. The king agreed to this, but the excitement did not subside. Then on March 20, the king abdicated in favor of his son Maximilian. Revolutionary movements broke out in the southwestern parts of Germany and spread throughout the country. On March 3, a demonstration of workers took place in Cologne, who demanded universal suffrage, the destruction of the standing army, and labor protection. The demonstration was dispersed by soldiers.

On March 6, riots broke out in Berlin. For several days, crowds of workers, students and artisans gathered in the suburbs of Berlin to discuss political issues. On March 13, street clashes broke out in Berlin, barricades were built, and there were clashes with the authorities. News of the events in Vienna (Metternich's resignation) further intensified the revolutionary outbreak. The king was forced to issue decrees in which he promised to convene a united Landtag, abolish censorship, and reform the German Confederation. On March 18, troops dispersed a demonstration at the royal palace. This caused popular indignation, barricades began to be built, clashes with troops occurred, and up to 400 people were killed. To prevent the troops from going over to the side of the rebels, the soldiers were withdrawn from Berlin on March 19. The king made concessions: the reactionary ministers were removed, an amnesty was proclaimed for political affairs, and the organization of the Civil Guard was allowed. On March 29, a liberal ministry was created, headed by Camphausen and Hansemann. In parallel with the revolutionary movements in the cities, uprisings in the villages took place. The peasants smashed the estates, demanded the abolition of feudal duties.

Under the influence of the March revolution, the upsurge of the labor movement in Berlin began. On March 26, a mass meeting of workers put forward a demand for the creation of a ministry of labor, made up of workers and entrepreneurs, general education, reduction of the standing army, and provision of disabled workers. The Prussian government suppressed the uprising in Poland despite popular protests. The sessions of the Prussian National Assembly opened on 22 May. The majority were the big bourgeoisie and moderate liberals. The main task of the meeting: the development of a constitution and the elimination of feudalism in the countryside. The National Assembly spoke out in favor of the redemption of feudal duties.

The main task of the revolution is the unification of the country. The majority of the bourgeoisie advocated the unification of Germany under Prussian rule without Austria, as they feared Slavic influence in a unified Germany. This path was called the Little German, there was another path - the unification of all parts of the German Confederation, headed by Austria, i.e. the Great German).

On May 18, 1848, the sessions of the National Assembly, elected to decide on the creation of a unified German state, opened in Frankfurt am Main. The interim ruler of the German Empire, the Austrian Archduke Johann, was elected. He appointed ministers who made up the central German government. But this government had no authority either in Germany or abroad. The discussion of the constitution dragged on.

On September 18, the uprising in Frankfurt am Main was suppressed, which broke out against the decision of an armistice with Denmark, with which there was a war for Schleswig and Holstein.

At the end of September 1848, a new uprising broke out in Baden. In the town of Lerah, a Provisional Government was created, headed by Struve, but it had neither the support of the local population, nor its own reform program, the uprising was suppressed.

In the second half of 1848, reactionary circles began to win. Vienna fell on November 1. In Berlin on November 3, a new ministry was formed from the feudal aristocracy and the old bureaucracy. The head of the ministry is a relative of the king, the Count of Brandenburg. On November 9-10, a counter-revolutionary coup took place in Prussia, troops occupied Berlin, all left-wing newspapers and democratic organizations were closed. The National Assembly was moved to the Berlin suburb of Brandenburg. The deputies responded with passive resistance. They appealed to the population with an appeal not to pay taxes.

On March 28, 1849, the Frankfurt Parliament adopted an imperial constitution. It provided for the creation of a single German empire (a single customs and monetary system), which included all the territories of the former German Union. Separate German states (Austria, Prussia, Bavaria, Saxony, etc.) retained their internal independence. But important functions of general German importance (foreign policy, general command of the army, etc.) were transferred to the central government. At the head of the empire was the emperor - one of the German sovereigns. The creation of a Reichstag from two chambers was envisaged: the "House of Representatives of States" and an elected "House of People's Representatives". The Constitution proclaimed political freedoms: the abolition of the estate privileges of the nobility, the abolition of serfdom, freedom of personality, conscience, speech and press, the right to submit a petition to the Reichstag. But the constitution was not recognized by any of the states (Prussia, Austria, Saxony). The Prussian king, who was elected emperor, refused to accept the crown.

In early May, uprisings in support of the constitution began in a number of provinces in Germany (Saxony, Rhineland, Westphalia, Baden). Prussian troops suppressed these uprisings everywhere. The Frankfurt parliament was transferred to Stuttgart, and on June 16, 1849, troops dispersed. The bourgeoisie, frightened by popular unrest, entered into an alliance with the nobility. The revolution did not fulfill its main goals - the unification of the country.

Revolution in Austria. The reasons for the revolution. Economic crisis, crop failures and peoples' liberation movement. News of the revolution in Italy, France and southern Germany hastened the explosion of the revolution. On March 13, 1848, barricades appeared on the streets of Vienna. Fighting with the troops began. A deputation from the bourgeoisie appealed to the king demanding the resignation of Metternich. The emperor agreed. The new ministry abolished censorship and allowed the creation of a national guard and an "academic legion" of students. On March 15, under pressure from the people, the government announced the imminent introduction of a constitution. The revolutionary movement spread rapidly throughout Austria.

On March 11, in Prague, a mass national assembly adopted a petition demanding: the introduction for the Czech Republic, Moravia and Silesia of a single legislative Sejm with the participation of the nobility, clergy, townspeople and peasants, the abolition of feudal duties for ransom, the organization of the National Guard, equality of the Czech and German languages, freedom of conscience , words, stamps, etc. The meeting elected a committee called St. Wenceslas. The committee led the movement and sent a deputation to Vienna with these demands. The emperor did not give a clear answer, so a new petition was drawn up. The Austrian government has partially yielded to the demands, in particular on the issue of languages.

On March 15, the revolution began in Budapest. Sandor Petofi became the leader of the revolution. The revolution began with a call for an uprising in his poem "National Song". The Hungarian liberal opposition demanded the convocation of a popular representation, the creation of a responsible ministry, freedom of conscience, press, assembly, and the abolition of feudal duties and estate privileges of the nobles. In early April, an independent government was formed in Budapest, headed by Count Batiani, and the leader of the liberals, Kossuth, was also included in it. The Diet decided to abolish the feudal duties for the ransom.

On April 25, an imperial decree was published introducing a constitution in Austria. The constitution created a parliament, the upper house of which was to consist of life and hereditary members appointed by the emperor; the lower house was elected, but on the basis of property qualifications. On May 15, shortly after the publication of the constitution, a massive popular uprising broke out in Vienna, in which the Central Political Committee of the National Guard (civilian militia) played the leading role. The government was forced to make concessions, to announce the abolition of the property qualification for voters and the convocation of the National Assembly, which was supposed to consist of one chamber. But on May 17, the emperor and his court left Vienna and fled to Innsbruck (the inhabitants were known for their conservatism). On May 26, the government dissolved the "academic legion", closed the university and some other educational institutions. The response to these actions of the authorities was a new popular uprising. On May 26-27, Vienna was again covered with barricades. The authorities were forced to cancel the order to disband the "academic legion", withdraw troops from the capital and entrust it with the protection of the National Guard. But only after a new revolutionary uprising, which took place on June 10, the workers were granted the right to vote.

The March revolution contributed to the rise of the national movement not only in the Czech Republic, but also in other Slavic regions of Austria. On April 26, an uprising broke out in Krakow, which was suppressed on the same day. On May 2, in Lviv, the meetings of the Ruska Head Council, elected by the Ukrainian population of Galicia, opened. Bishop Yekimovich became the chairman of the Rada.

The Russian head council aimed to achieve equalization in the rights of the Orthodox Church with the Catholic one, the introduction of the Ukrainian language in educational and state institutions, the publication of books and newspapers in the Ukrainian language.

The Polish nobility of the region opposed the Ukrainian movement, denying the Ukrainians the independence of their traditions and language, considering it a kind of Polish language.

The Austrian government took advantage of the contradictions between the Polish and Ukrainian populations of Galicia. It allowed the existence of the Russian head council, since it did not oppose the integrity of the Austrian Empire. As a result of the activities of the Rada Ukrainian language in Galicia gradually gained recognition.

The population of the Transcarpathian Ukraine rose to fight for freedom and independence. The news of the revolutionary events in Budapest on March 13-15 gave impetus to the revolutionary struggle in Uzhgorod and other cities of Transcarpathian Ukraine, which was considered an integral part of the Hungarian kingdom. In the cities and villages of Transcarpathia, local self-government bodies arose and detachments of the National Guard were created. At first, broad strata of the Transcarpathian population acted as a united front, but sharp contradictions between the Ukrainians and the Hungarians soon emerged. The Hungarian landowners, who owned large land holdings in Transcarpathian Ukraine, were hostile to the Ukrainian national movement, since it was combined with the struggle of the peasants against the feudal order. The news of the abolition of feudal duties by the Hungarian Diet roused the peasants of the Transcarpathian Ukraine to fight. Landowners refused to comply with the laws on the abolition of corvee and tithe and sought to restore the old order. The peasants demanded the abolition of all payments made to the nobility and the clergy, and the transfer of landlord lands to peasant communities.

The Hungarian revolutionary government, headed by the liberal nobility, opposed the demands of the peasantry of the Transcarpathian Ukraine and the national movement. The intelligentsia of Transcarpathian Ukraine, headed by the well-known public figure A.I. Dobryansky, put forward the idea of autonomy of this region and its unification with the Ukrainian part of Galicia. The Austrian government, taking advantage of the contradictions between the Hungarians and the Ukrainians, approved this project, but did nothing to implement it.

In the spring of 1848, the national struggle of the South Slavs intensified. In March 1848, the Serbian communities of Hungary began to file petitions in which they demanded equalization of the rights of the Orthodox Church with the Catholic Church and the introduction of the Serbian language in local government. On May 1, the Serbian Assembly gathered in Karlovice, which elected the patriarch (Metropolitan Rayacic); On May 3, the Assembly proclaimed the alliance of Vojvodina with Croatia (within the framework of the Austrian monarchy). The assembly elected the Main Odbor (committee) (chaired by Stratimirovich). Local committees were formed in the provinces, which took political power into their own hands. The population armed itself, created partisan detachments, joined the ranks of the national militia, the number of which soon reached 15 thousand people. Residents of the Serbian principality came to the aid of the Serbs of Vojvodina. A committee was created in Belgrade, which led the agitation for the unification of all southern Slavs into a single state, independent from both Turkey and Austria.

Hungarian landowners who owned large lands in Vojvodina were hostile to the Serbian national movement, especially since it was combined with peasant uprisings against feudalism. They obtained from the emperor a decree declaring the convocation of the Assembly and the choice of the patriarch illegal. Hungarian troops were brought into the territory of Vojvodina, which suppressed any demonstrations. The movement began to decline. The Conservative Party, led by Rayachic, took over the Liberal Party, led by Stratimirovich. The economic and political weakness of the Serbian bourgeoisie largely contributed to this outcome.

On April 25, the Croatian ban (governor) Baron Jelacic issued a decree abolishing some of the feudal duties (with the simultaneous reward of the landlords at the expense of the state). But the unrest in the villages continued. Jelachich sent armed detachments against the peasants.

On June 5, the Croatian Assembly (National Assembly) was opened in Zagreb. Sabor decided to overthrow the Habsburg dynasty and to divide the landowners' lands. However, the very next day members of the Sabor, frightened by new peasant uprisings, destroyed all the protocols of these decisions. It was decided to create three common ministries for Hungary and Croatia: military, foreign affairs, finance. But these demands were also rejected by the Hungarians. This position of the Hungarians made an armed struggle between them and the Croats inevitable.

The center of the national movement of the Slavic peoples of Austria in 1848 was the Czech Republic, the most developed of the Slavic regions of the Habsburg monarchy. At the end of April, the idea arose of convening a congress of delegates from all Slavic peoples of Austria to organize resistance to plans to include all of Austria with all its Slavic lands into the future German Empire (the implementation of this plan threatened them with forcible Germanization).

The opening of the Slavic Congress took place on June 2 in Prague. It was attended by 340 delegates (237 Czechs, 42 representatives from the South Slavs, 60 Poles and Rusyns, 1 Russian - M. A. Bakunin). Moderately conservative politician Palacky was chaired. The congress was divided into three sections: Czech-Slovak, Polish-Rusyn, South Slavic. The congress revealed a rather significant difference in the national aspirations of the representatives of individual Slavic peoples. If the Czechs sought national and political autonomy within the framework of a reorganized federal Austria, the Poles strove, first of all, to restore the independence of Poland. These and other disagreements impeded the work of the congress.

On June 12, the Slavic Congress adopted an appeal to the peoples of Europe, which put forward the idea of transforming the Austrian Empire into a "union of equal peoples" and expressed the hope that this idea would be supported by the entire "enlightened Europe".

On June 12, an armed struggle broke out on the streets of Prague between the insurgent people and the government troops, which put an end to the work of the Slavic Congress. The uprising began, spontaneously, in response to the defiant behavior of the Austrian Field Marshal Windischgrez.

On June 17, after fierce fighting that lasted for five days, the uprising in Prague was suppressed. This ended the first stage of the Czech national movement in 1848.

Meetings of the Austrian National Assembly opened on 22 July. The majority of its members were moderate liberals, who strove to transform the Austrian Empire into a bourgeois constitutional state in which the dominant position would belong to the German bourgeoisie.

In the very first days of the meetings, a dispute arose over the question of the language in which the debate was to be conducted. The deputies of the Slavic regions insisted on the recognition of the equality of the Slavic languages with the German language. However, the majority of votes for the German language at the meeting. One of the most important tasks facing the Austrian bourgeois revolution was the solution of the agrarian question. On July 26, Deputy Kudlich's proposals were made to abolish all restrictions on the personal freedom of a peasant, to abolish corvee and tithe; Kudlich proposed to transfer the question of remuneration to landowners for the abolition of their feudal privileges to a special commission. The project sparked a heated debate. The law of September 7, 1848 canceled only the personal obligations of the peasantry without redemption. Corvée, quitrent and other material duties were canceled only on the basis of a ransom, the amount of which was to be 20 times greater than the amount of annual peasant payments. 2/3 of the redemption payments were paid by the peasants, 1/3 was paid by the state. As a result of this elimination of feudal privileges, the landlords were paid huge sums (a total of 600 million guilders).

On August 12, the emperor and his court returned from Innsbruck to Vienna. On August 19, the already low wages of workers employed in public works in Vienna were cut. On 23 August, workers organized a demonstration to protest this order; clashes broke out between demonstrators and National Guards; several hundred people were wounded and several dozen were killed. The Austrian government took action against the liberation movement in Hungary. On September 4, Jelačić, who, as the leader of the Croatian landlords, entered into an agreement with the Austrian court, was appointed commander of all the imperial troops in Hungary. On September 11, he crossed the Drava River and entered Hungarian territory. The attack of the Austrian troops on Hungary caused a new revolutionary upsurge in it. Under pressure from the masses, the National Assembly was forced to take the path of more decisive action. A Defense Committee headed by Kossuth was elected. On October 3, an imperial decree was published, which dissolved the Hungarian Sejm, declared illegal all actions of the Hungarian revolutionary authorities, introduced martial law in Hungary and instructed Jelacic to restore "order" in it. On October 5, units of the Viennese garrison were sent to help Jelachich. This news caused great indignation among the population of Vienna. The next day, a large crowd of people forcibly prevented the dispatch of new reinforcements to Jelachich. On the same day, a new uprising broke out in Vienna, in which workers, students, and national guards played a decisive role. The insurgents demanded the abolition of the decree on October 3, the withdrawal of troops from Vienna and the creation of a new, democratic ministry. After fierce street fighting, the city passed into the hands of the insurgent people. The Minister of War, Baron Latour, was hanged. The emperor and his court fled to Olo mouts (Moravia).

Small detachments of volunteers arrived from the provinces to help Vienna. By the end of October, Vienna was completely cut off from the outside world and completely surrounded by the army of Windischgrez. On October 30, after a fierce bombardment, the defenders of Vienna laid down their arms, but the workers of the suburbs continued to resist. On November 1, the imperial troops entered the city.

The uprising was suppressed. A brutal reprisal against members of the movement began: thousands of people were arrested, many hundreds were convicted, several dozen were hanged or shot. The Reichstag was transferred to the town of Kremzir (Kromeriz) and then dissolved. The new constitution, published on March 4, 1849, was of an aristocratic and bureaucratic centralist character.

The triumph of the counter-revolution in Vienna entailed an intensification of reaction in other parts of Austria as well. On November 2, the uprising of the Polish democrats in Lvov was suppressed. 2 January 1849 reptile army

Windischgreetz occupied the capital of Hungary - Budapest. The loss of Budapest did not break the resistance of the Hungarian people. On April 14, 1849, the Hungarian Sejm in Debrecen proclaimed the state independence of Hungary and put the national government of Kossuth at its head. In the course of hostilities, a turning point occurred. The Hungarian revolutionary army successfully advanced westward, pursuing the retreating Austrian troops.

At this critical moment for the Habsburgs, Tsarist Russia came to the aid of the Austrian emperor. In May 1849, a 100,000-strong Russian army under the command of Field Marshal Paskevich invaded Hungary. Hungarian protests were suppressed.

The defeat of the revolution led to the restoration of absolutism in the empire. But its restoration was not complete. Feudal duties were abolished.

Hungary was divided into five governorships. Transylvania, Croatia-Slavonia, Serbian Vojvodina and Temisvarsky Banat were placed under direct Austrian control. Vienna appointed a governor. Increased Germanization of the empire. German was declared the state language of the empire.

Revolution in Italy.

In the second half of the 40s. there was an aggravation of the contradictions of the feudal-absolutist system in all states of Italy, the struggle of the liberal bourgeoisie and part of the nobility intensified, which demanded reforming the reactionary state systems, deepening bourgeois transformations, and the unification of Italy. The hopes of the liberal camp were associated with the election of a new pope, he was predicted to play the role of a unifier of the country and a reformer. In many regions of Italy, there were massive demonstrations demanding reforms and unification of the country. The rulers of the regions of Italy dealt with popular demonstrations in different ways, in the Kingdom of Naples popular demonstrations were suppressed by troops, in Parma and Modena, the governments turned to Austria, which sent its troops there. In the Kingdom of Sardinia, the Duchy of Tuscany and the Papal State, some reforms were introduced: censorship was softened, a number of judicial and administrative reforms were carried out.

In the Lombardo-Venice region, the tax oppression intensified, weighed down by national suppression. At first, the population began to passively resist the Austrian authorities, the patriots appealed from January 1, 1848 to stop smoking and buying tobacco so that the Austrians would not receive income from taxes, since Austria received huge revenues from the tobacco monopoly. The authorities provoked clashes between the population and the police and troops, there were casualties, which caused massive outrage and protests in other cities of the Lombardo-Venetian region, and then in the rest of Italy.

Unrest grew, and on January 12, 1848, an uprising broke out in the capital of Sicily, Palermo. It was led by secret circles of patriotic democrats and liberals, who formed insurgent units and arranged the supply of weapons. In February, almost all of Sicily was controlled by the Provisional Government created by the rebels. These events marked the beginning of the 1848 revolution in Italy.

On January 17, an uprising broke out near Naples. The rebels moved towards Naples, violent demonstrations continued in the capital. Ferdinand II made concessions: he granted Sicily limited autonomy, expanded the rights of provincial councils, and pardoned political prisoners. The people demanded a constitution. On February 11, the text of the constitution was published. According to which a bicameral parliament was introduced, the king appointed the chamber of peers, the chamber of deputies was elected, but the king retained great powers.

Under the influence of the revolution in southern Italy, powerful popular demonstrations and pressure from liberal circles in February - March 1848, the Duchy of Tuscany, the Papal State and the Kingdom of Sardinia received constitutions. In the latter, Karl Albert introduced the Albertine Statute named after him. This constitution retained the executive power for the king, endowed the king and a bicameral parliament with legislative functions. The senate was formed by the king himself from the princes of the royal house, representatives of the highest church hierarchy, officials, generals, large owners. The Chamber of Deputies was elected on the basis of age, educational and property qualifications. Provided, albeit with some restrictions, freedom of assembly and the press. After the unification of Italy, the Albertine Statute was adopted as the Basic Law of the country, and it remained so for almost 100 years.

The news of the revolution in Austria raised the Lombard-Venetian region to fight. The uprising of 18 March 1848 in Venice forced the Austrians to surrender. On March 23, the Provisional Government of the Venetian Republic was formed. In the capital of Lombardy, Milan, the rebels from March 18 to 22 fought barricade battles with the Austrian garrison and expelled it from the city. The municipality of Milan declared itself the Provisional Government. The Austrians left Parma and Modena.

Karl Albert on March 25, 1848 spoke out for the freedom of Italy against Austria. This was Italy's first war of independence. The Sardinian kingdom was supported by Lombard and Venetian volunteers, papal, Tuscan and Neapolitan troops. At first, the combined Italian forces acted successfully, but then Pope Pius IX refused to actively participate in the war. His example was followed by Tuscany and the Neapolitan king Ferdinand II, who withdrew his army. The Austrian field marshal Radetzky, who went on the offensive, on July 24-25, 1848, defeated the Sardinian troops in the battle near Kustoza and forced Charles Albert to sign an armistice. Austria regained control over Lombardy, the dukes who had fled from their countries returned to Modena and Parma.

An uprising began in the Papal Kingdom. Pius IX, fearing the force of the uprising, fled from Rome. There was elected on January 21, 1849, the Constituent Assembly, which deprived the pope of secular power and proclaimed a republic. In March, Mazzini was elected head of the government of the Roman Republic. In Rome, during February-April 1849, a number of reforms were carried out: a decree was issued on the nationalization of church lands and their division into small plots and transfer to the poor, a progressive tax on industrialists and merchants was introduced, salt and tobacco monopolies were abolished, ecclesiastical courts were liquidated and a civil tribunal, separation of the school from the church.

Under the influence of events in Rome, unrest intensified in neighboring Tuscany. Duke Leopold II, who left Florence, was deposed, power passed to the Provisional Government.

These events contributed to the renewal of the war with Austria with the aim of liberating Lombardy and Venice. Karl Albert, threatened with the loss of the prestige of the House of Savoy in the eyes of the Italians, began military operations, but the Sardinian army was again defeated. The king abdicated the throne in favor of the son of Victor Emmanuel II. He immediately concluded another truce. The Austrian victory led to the restoration of Habsburg rule in Lombardy and the return of Leopold II from the Habsburg house to Tuscany. The defeat of the Kingdom of Sardinia complicated the position of the Roman Republic, which was forced to defend itself against the invaders. Neapolitan troops invaded from the south, and the Austrians advanced from the north. A French expeditionary force landed in the immediate vicinity of Rome. The Roman republicans, led by Garibaldi, managed to repel the onslaught, but on July 3, 1849, the 35,000-strong French army, after an artillery bombardment, seized the city by storm. The French garrison was located in Rome and remained there until 1871.

The republic in Venice held out the longest. Austrian troops besieged the city for two months. Its defenders, exhausted by shelling, hunger and epidemics of typhus and cholera, surrendered on August 22, 1849. The revolution in Italy is over.

The stormy revolutionary events of 1848-1849 did not bring national unification and did not free the country from the Austrian diktat. But the peculiarity of the revolution in Italy was its national scale, which had important consequences. The revolution shook, though did not destroy, absolutist regimes. The exception was the Kingdom of Sardinia (Piedmont), which was the only one of all to retain the constitution conquered by the revolution. It was it that played the most important role in the subsequent stages of the struggle for the creation of a unitary state.

Results and significance of revolutions. The defeat of the revolutions was followed by a general European reaction that stretched out for a whole decade. Participants in the revolutions were persecuted, democratic organizations were closed, censorship was tightened.

But the events of 1848-49. influenced the ruling circles. During the revolutions, the authorities made significant concessions; some of them, albeit in a truncated form, survived after the defeat of the revolutions.

The most significant were the transformations in the agrarian question. In Austria, Hungary, the Czech Republic, in some German states, for example, in Bavaria, the remnants of serfdom were eliminated, and the peasants had the opportunity to free themselves from feudal dependence. This objectively contributed to the spread of capitalist relations in the countryside. In Prussia, where the emancipation of the peasants from feudal obligations went on even before the revolution, laws were passed, thanks to which the final destruction of feudal relations and the bourgeois coup was completed within one post-revolutionary decade.

The revolutions have led to certain changes in the political sphere. In France, the new constitution of 1848 established a republic, the basis of which was proclaimed "family, labor, property and public order." This republic was more democratic than the July Monarchy that preceded it. The most significant achievement of democracy was the constitutional universal suffrage for men. Even after the coup d'état of Louis-Bonaparte, and the introduction of additional restrictions on qualifications, this institution remained in the political system.

The Prussian Constitution, adopted in 1848 in the wake of the revolution, was revised in 1850 with the aim of removing "liberal" elements from it. But it preserved articles declaring the equality of citizens before the law, freedom of speech, assembly, unions, and personal inviolability. The constitution prohibited censorship of print media. She established a bicameral parliament, endowed with legislative powers, which became a permanent institution of state power. The lower house of the Prussian parliament was elected. The Piedmontese Statute of 1848, which later became the constitution of all of Italy, also provided for a bicameral system and the election of members of the lower house. She received a decisive voice in the formation of the budget and the approval of taxes; the responsibility of the ministers to the deputies was established.

Thus, thanks to the adoption of constitutions and electoral laws, often very curtailed, the bourgeois circles gained access to power. New elements were gradually introduced into the state-political system, which became its integral part. Europe followed the path of democratizing its political system. The revolutions made this movement irreversible. They showed all the pressing problems, forcing governments to solve them in different ways. The ruling circles were frightened by the strength of the popular movement and sought to avoid another explosion through reforms. The revolutions created the basis for the unification of Germany and Italy, for the bourgeois reforms in the Austrian Empire, which brought Hungary autonomy and greater independence. The revolutions accelerated the development of European countries.

Revolution of 1848-1849 flared up not only against internal reaction, but also threatened to fundamentally undermine the entire European system of international relations, formed on the basis of the reactionary Vienna treatises of 1815.

In France, the revolution of 1848 put in power a class of the French bourgeoisie, whose circles pursued an aggressive policy, a policy of expanding colonial possessions, which sooner or later was to lead to international clashes.

The revolutions in Italy and Germany were aimed at the destruction of feudal fragmentation, to the creation of strong national states: a united Italy and a united Germany.

The Italian and Hungarian revolutions led to the collapse of the Austrian Empire. The Polish revolutionary movement, whose goal was to restore an independent Poland, threatened not only the Austrian Empire, but also the Prussian monarchy and Tsarist Russia.

In international relations 1848-1849 the central question was whether the system of 1815 would survive or it would collapse and the reunification of Germany and Italy into independent states would take place. The creation of a unified Germany would mean the destruction of the feudal fragmentation of German lands and the elimination of the Austro-Prussian rivalry for the unification of Germany. But the preservation of feudal fragmentation and Austro-Prussian rivalry was beneficial to neighboring major powers such as France and England, which corresponded to the foreign policy interests of the ruling classes. Tsarist diplomacy also supported the fragmentation of Germany, which contributed to the strengthening of Russia's influence in European affairs.

Attempts to unite Germany under the hegemony of Prussia aroused alarm and opposition, both from tsarist Russia and from England and France. The ruling classes of England feared the strengthening of Prussia at the expense of Denmark. The French bourgeoisie saw a threat for itself in the possible absorption by Prussia not only of Schleswig and Holstein, which belonged to Denmark, but also of small German states. The governments of Russia, France and England were even more hostile to the revolutionary democratic path of uniting Germany. For Nicholas I, the struggle against the revolutionary unification of Germany meant the defense of the autocratic-serf system. Russian Empire... Between bourgeois France and bourgeois England, on the one hand, and the feudal-absolutist states of Russia and Austria, on the other, there was a certain commonality of positions in German affairs, which could not but affect the international relations of 1848-1849.

The entire foreign policy of the Provisional Government of France, formed during the revolution of 1848-1849, was determined by the fear of intervention, the fear of meeting an external enemy. The government tried to avoid any complications in relations with the reactionary governments of Europe. The French government considered the main means of avoiding intervention to ensure peace with England. Without British subsidies, a war with the French Republic would have been too much for the frustrated finances of Austria, Russia and Prussia. After becoming foreign minister, Lamartine immediately wrote to the British ambassador in Paris, Lord Normenby and representatives of other states, that the republican form of the new government did not change France's place in Europe, nor its sincere intentions to maintain relations of good agreement between the powers.

On March 4, 1848, Lamartine sent a circular to the representatives of the French Republic abroad, assuring foreign governments that France would not start a war with the aim of repealing the treaties of 1815. “The treatises of 1815 no longer exist in the eyes of the French republic as a right; however, the territorial provisions of these treatises are a fact that it admits as the basis and starting point in its relations with other nations, ”it said.

Rejecting the idea of revolutionary intervention in the affairs of other countries, the circular stated that in some cases the republic has the right to carry out such intervention. Lamartine continued to insist that the universal brotherhood of peoples can only be established by peaceful means. The revolutionary democrats and socialists in France did not believe in the peaceful realization of the idea of the brotherhood of peoples and insisted on active assistance to the revolutionary movements throughout Europe. Assistance to revolutionary movements, the restoration of Poland within the borders of 1772 as a stronghold and ally of France, the rapprochement of France with liberated Italy and a united Germany - this was the foreign policy program of these groups.

After the February Revolution, France's position in Europe changed dramatically. France distanced itself from Austria, defended the integrity, neutrality and independence of Switzerland. Lamartine's dream was an alliance with England, small states and "liberal" Prussia. He believed that the kinship of political principles could ensure the solidarity of England, France and Prussia in foreign policy. France's foreign policy was weak and passive. Even in Italy, on whose territory Lamartine wanted to eradicate Austrian influence and replace it with French, the government did not dare to take action. Under the Provisional Government, France was isolated and had no allies

The revolutionary upheavals in 1848 gripped almost all of Western Europe, and almost all governments were alarmed by the unrest in their countries. The revolutionary events in Italy, the March revolutions in the German states and in the Austrian Empire, diverted attention from the French Republic in the first weeks of its existence and made a general opposition to it completely impossible.

In contrast to 1830, when England immediately after the July revolution recognized the new French government, G. Palmerston was in no hurry with the official recognition of the Second Republic and maintained only de facto relations with it. The republic was recognized by the USA, Switzerland, Belgium, Spain, but England was waiting to find out how stable the new government in France was. He hastened to exchange views with the Dutch government about the threat of French revolutionary intervention in Belgian affairs. On this basis, the rapprochement of Great Britain, Belgium and Holland took place.

G. Palmerston feared the triumph of French influence in northern Italy. The best way to prevent France in this matter was considered a general agreement of European governments on the measures to be taken if she attacks neighboring states. He hoped to reach an agreement on this on the basis of the principle of non-interference of all states in the affairs of Italy and Switzerland. In fact, G. Palmerston was ready to help create a strong buffer state in northern Italy under British influence. Taking advantage of the weakness of the foreign policy of the Provisional Government, the British diplomat intended wherever possible to oust French influence and replace it with English. However, his policy failed.

The news of the February revolution aroused rage in Nicholas I. The king never recognized Louis Philippe as the legitimate monarch, but the republic was even worse. Nicholas I wanted to move his army against France and crush the revolution. Aware of the lack of funds to oppose France, he was in a hurry to create an armed barrier against the approaching revolution from the west and tried to strengthen ties with Berlin and Vienna. Unable to attack France, Nicholas I decided to break off diplomatic relations with her. But circumstances forced the tsar in 1848 to take a more restrained position towards France than during the July events of 1830. The revolutions that took place in the German states and in Austria led to the fact that even the tsar's intentions to break off diplomatic relations with republican France remained unfulfilled.

After the March revolutions in Vienna and Berlin, the tsar found himself in complete isolation. The methods of maneuvering and compromises that the Prussian king used in the fight against the revolution were completely intolerable for Nicholas I. Nicholas regretted that the revolution had shaken the foundations of the old, absolutist Prussia. He feared the creation of a unified Germany. He was especially afraid of the revolutionary unification of Germany, but did not want to allow the unification of Germany under the leadership of the Prussian Junkers. Nicholas I believed that the revolution could spread to Poznan, Galicia and the Kingdom of Poland, could approach the borders of Russia. The tsarist manifesto, published on March 14 after the revolutions in Austria and Prussia, explained that Russia was taking a defensive position and had not yet intervened in internal transformations in Western Europe. In an explanatory article by K.V. Nesselrode stipulated that, while protecting the treatises of 1815, Russia "will not miss the distribution of borders between states and will not tolerate that in the event of a change in the political equilibrium and any other distribution of areas, such an application would be turned to the detriment of the Empire."

After the revolutions in Austria and Prussia, the tsar feared the revolutionary unification of Germany and the dominance of aggressive Prussia in it. Under such conditions, a break with France, despite the proclamation of a republic there, became undesirable for the tsar. In their hostile attitude towards the revolution in Germany, bourgeois France and England fully agreed with the tsar, who strove to prevent Germany from becoming a unified state.

After the dissolution of the Frankfurt parliament in 1849, which set itself the goal of uniting Germany, the dream of this unification around Prussia did not leave broad strata of the German bourgeoisie. Nicholas I never wanted to allow this unification. Under the influence of Nicholas I, Frederick William IV refused to accept the German imperial crown from the Frankfurt parliament. But under the influence of a common desire for unification, even the reactionary Prussian ministry of the Count of Brandenburg made in 1849-1850. some steps towards the reorganization of the impotent German Confederation. Then Nicholas I supported the Austrian Chancellor Schwarzenberg, who announced that Austria would not tolerate the strengthening of Prussia. On this issue, Nicholas I completely agreed with Austrian diplomacy.

On August 2, 1850, representatives of Russia, France, England and Austria signed an agreement in London, which secured the possession of Holstein to Denmark. This was the first blow dealt to Prussia. In November 1850, a new conflict broke out between Austria and Prussia over Hesse. After the intervention of Nicholas I in the city of Olmutz, on November 29, 1850, an agreement was signed between Prussia and Austria, and Prussia had to completely reconcile.

The agreement was preceded by an attempt by Prussia to create in 1849-1850. under his leadership, the union of 26 German states and an all-German parliament, which provoked resistance from Austria, as well as dissatisfaction with Russia, France and Great Britain. By agreement, Prussia agreed to restore the fragmented German Confederation, created in accordance with the decision of the Congress of Vienna in 1814-1815. and pledged to let the Austrian troops pass to Hesse-Kassel and Holstein to suppress revolutionary uprisings there. This agreement was the last victory of Austrian diplomacy against Prussia. This "Olmut humiliation" was remembered throughout Germany as the handiwork of Nicholas I.

Revolution in France

February revolution, its results. Provisional government, its composition. Workers' demands and government policies. Policy towards peasants and the petty bourgeoisie. Aggravation of the socio-political struggle. The role of revolutionary clubs. Forms.

The Constituent Assembly and its Activities. The descending line of the revolution (concept of Marx). An offensive against the working class. June uprising in Paris. The composition of its participants, their requirements. The meaning of the uprising. Assessment of the uprising in modern historiography.

The dictatorship of the bourgeois republicans. Constitution of the Second Republic (1848) Reasons the election of Louis Bonaparte as president. "Second Bonapartism". The rise of the democratic movement in the spring of 1849. "New Mountain". Decay and fall of the bourgeois republicans. Legislative Assembly and its composition. Mountain performance and the reasons for his defeat.

Parliamentary dictatorship of the "party of order". Abolition of universal suffrage. Bonapartist coup on December 2, 1851 Resistance of the republicans in Paris and the provinces, the reasons for its weakness. Establishment of the Second Empire.

The place of the revolution of 1848 among the French revolutions of the late 18th - 19th centuries. Historiography of the 1848 revolution in France.

Revolution in Germany

Revolutions in the west of the country. March revolution in Prussia. Creation of liberal ministries. The problem of national unification. Pre-parliament. Republican movement in the spring of 1848 Uprising in Baden and Poznan. Polish National Movement.