Empress Elizaveta Petrovna - biography, personal life of the empress: a cheerful princess. Biography of Empress Elizabeth I Petrovna The reign of Elizabeth Petrovna Catherine 2

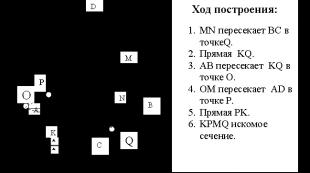

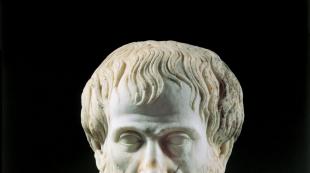

I. Argunov "Portrait of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna"

“Elizabeth has always had a passion for rearrangements, restructuring and moving; in this “she inherited the energy of her father, built palaces in 24 hours and covered the then route from Moscow to St. Petersburg in two days” (V. Klyuchevsky).

Empress Elizaveta Petrovna (1709-1761)- daughter of Peter I, born before the church marriage with his second wife, the future Catherine I.

Heinrich Buchholz Portrait of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna in pearls. 1768

Russian Empress since November 25 (December 6), 1741, from the Romanov dynasty, daughter of Peter I and Catherine I, the last ruler of Russia, who was Romanov “by blood.”

Elizaveta was born in the village of Kolomenskoye. This day was solemn: Peter I entered Moscow, wanting to celebrate his victory over Charles XII in the old capital. Swedish prisoners were taken behind him. The Emperor intended to immediately celebrate the Poltava victory, but upon entering the capital he was notified of the birth of his daughter. “Let’s put off the victory celebration and hasten to congratulate my daughter on her entry into the world,” he said. Peter found Catherine and the newborn baby healthy and celebrated with a feast.

Louis Caravaque Portrait of Princess Elizaveta Petrovna as a child. Russian Museum, Mikhailovsky Castle.

Being only eight years old, Princess Elizabeth already attracted attention with her beauty. In 1717, both daughters, Anna and Elizabeth, greeted Peter returning from abroad, dressed in Spanish attire.

Louis Caravaque Portrait of Anna Petrovna and Elizaveta Petrovna. 1717

Then the French ambassador noticed that the sovereign’s youngest daughter seemed unusually beautiful in this outfit. The following year, 1718, assemblies were introduced, and both princesses appeared there in dresses of different colors, embroidered with gold and silver, and in headdresses sparkling with diamonds. Everyone admired Elizabeth's dancing skills. In addition to her ease of movement, she was distinguished by resourcefulness and ingenuity, constantly inventing new figures. The French envoy Levi noted at the same time that Elizabeth could be called a perfect beauty if not for her snub nose and reddish hair.

Elizabeth, indeed, had a snub nose, and this nose (under pain of punishment) was painted by artists only from the full face, from its best side. And in profile there are almost no portraits of Elizabeth, except for the occasional medallion on a bone by Rastrelli and the portrait of Buchholz presented above.

Ivan Nikitin Portrait of Princess Elizaveta Petrovna as a child.

The princess's upbringing could not have been particularly successful, especially since her mother was completely illiterate. But she was taught in French, and Catherine constantly insisted that there were important reasons for her to know French better than other subjects.

This reason, as is known, was the strong desire of her parents to marry Elizabeth to one of the persons of the French royal blood, for example, to King Louis XV. However, to all persistent proposals to intermarry with the French Bourbons, they responded with a polite but decisive refusal.

Unknown artist of the mid-18th century Portrait of Elizaveta Petrovna in her youth.

In all other respects, Elizabeth’s education was not very burdensome; she never received a decent systematic education. Her time was filled with horse riding, hunting, rowing and caring for her beauty.

Georg Christoph Groot Portrait of Empress Elizaveta Petrovna on a horse with a little black arap. 1743

After her parents' marriage, she bore the title of princess. The will of Catherine I of 1727 provided for the rights of Elizabeth and her descendants to the throne after Peter II and Anna Petrovna.

Her father surrounded her and her older sister Anna with splendor and luxury as future brides of foreign princes, but was not very involved in raising them. Elizaveta grew up under the supervision of “mammies” and peasant nurses, which is why she learned and fell in love with Russian morals and customs. For training foreign languages teachers of German, French, and Italian languages. They were taught grace and elegance by a French dance master. Russian and European cultures shaped the character and habits of the future empress. The historian V. Klyuchevsky wrote: “From Vespers she went to the ball, and from the ball she kept up with Matins, she passionately loved French performances and knew all the gastronomic secrets of Russian cuisine to a fine degree.”

Louis Caravaque "Portrait of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna"

Elizaveta Petrovna’s personal life did not work out: Peter I tried to marry her off to the French Dauphin Louis XV, but it did not work out. Then she rejected French, Portuguese and Persian applicants. Finally, Elizabeth agreed to marry the Holstein prince Karl-August, but he suddenly died... At one time, her marriage with the young Emperor Peter II, who passionately fell in love with his aunt, was discussed.

Anna Ioannovna (Elizabeth's great-aunt), who ascended the throne in 1730, ordered her to live in St. Petersburg, but Elizabeth did not want to tease the empress, who hated her, with her presence at court and deliberately led an idle lifestyle, often disappearing in the Alexandrovskaya Sloboda, where she communicated mainly with ordinary people, took part in their dances and games. Next to Elizaveta Petrovna’s house there were barracks of the Preobrazhensky Regiment. The guards loved the future empress for her simplicity and good attitude towards them.

Perevoro

After the death of Peter II, engaged to Catherine Dolgorukova, from smallpox in January 1730, Elizabeth, despite the will of Catherine I, was not actually considered as one of the contenders for the throne, which was transferred to her cousin Anna Ioannovna. During her reign (1730-1740), Tsarevna Elizabeth was in disgrace. Those dissatisfied with Anna Ioannovna and Biron had high hopes for the daughter of Peter the Great.

After the baby John VI was proclaimed emperor, Elizabeth Petrovna’s life changed: she began to visit the court more often, meeting with Russian dignitaries and foreign ambassadors, who, in general, persuaded Elizabeth to take decisive action.

Taking advantage of the decline in authority and influence of power during the regency of Anna Leopoldovna, on the night of November 25 (December 6), 1741, 32-year-old Elizabeth, accompanied by Count M.I. Vorontsov, physician Lestocq and her music teacher Schwartz, said “Guys! You know whose daughter I am, follow me! Just as you served my father, so will you serve me with your loyalty!” raised behind her the grenadier company of the Preobrazhensky Regiment.

Fyodor Moskovitin Oath of the Preobrazhensky Regiment to Empress Elizabeth Petrovna.

Having encountered no resistance, with the help of 308 loyal guards, she proclaimed herself the new queen, ordering the imprisonment of the young Ivan VI in the fortress and the arrest of the entire Brunswick family (relatives of Anna Ioannovna, including the regent of Ivan VI, Anna Leopoldovna) and her adherents.

The favorites of the former empress Minich, Levenwolde and Osterman were sentenced to death, replaced by exile to Siberia - in order to show Europe the tolerance of the new autocrat.

Elizabeth was almost not involved in state affairs, entrusting them to her favorites - the brothers Razumovsky, Shuvalov, Vorontsov, A.P. Bestuzhev-Ryumin. Generally, domestic politics Elizaveta Petrovna was distinguished by her stability and focus on growing the authority and power of state power.

Taras Shevchenko Empress Elizaveta Petrovna and Suvorov (engraving). 1850s

Based on a number of signs, it can be said that Elizaveta Petrovna’s course was the first step towards the policy of enlightened absolutism, which was then carried out under Catherine II.

She generously rewarded the participants in the coup: money, titles, noble dignity, ranks...

Surrounding herself with favorites (mostly these were Russian people: the Razumovskys, Shuvalovs, Vorontsovs, etc.), she did not allow any of them to achieve complete dominance, although intrigues and the struggle for influence continued at court...

HER. Lansere "Empress Elizaveta Petrovna in Tsarskoe Selo"

The artist Lanceray masterfully conveys the unity of the lifestyle and art style of past eras. The entrance of Elizaveta Petrovna with her retinue is interpreted as a theatrical performance, where the majestic figure of the empress is perceived as a continuation of the facade of the palace. The composition is based on the contrast of lush baroque architecture and the deserted ground floor of the park. The artist ironically juxtaposes the massiveness of architectural forms, monumental sculpture and characters. He is fascinated by the roll call of elements architectural decor and toilet parts. The Empress's train resembles a raised theatrical curtain, behind which we are caught by surprise by the court actors rushing to play their usual roles. Hidden in the jumble of faces and figures is a “hidden character” – an Arab little girl, diligently carrying the imperial train. A curious detail was not hidden from the artist’s gaze either – an unclosed snuffbox in the hasty hands of the gentleman’s favorite. Flashing patterns and color spots create a feeling of a revived moment of the past

The period of Elizabeth's reign was a period of luxury and excess. Masquerade balls were regularly held at court, and in the first ten years, so-called “metamorphoses” were held, when ladies dressed up in men's suits, and men in ladies' suits.

Georg Caspar Prenner Equestrian portrait of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna with her retinue. 1750-55 Timing belt

In the winter of 1747, the Empress issued a decree, referred to in history as the “hair regulation,” commanding all court ladies to cut their hair bald, and gave everyone “black tousled wigs” to wear until they grew back. City ladies were allowed by decree to keep their hair, but wear the same black wigs on top. The reason for the order was that the empress could not remove the powder from her hair and decided to dye it black. However, this did not help and she had to cut off her hair completely and wear a black wig.

Elizaveta Petrovna set the tone and was a trendsetter. The Empress's wardrobe consisted of up to 45 thousand dresses.

Alexander Benois Empress Elizaveta Petrovna deigns to stroll along the noble streets of St. Petersburg. 1903

Domestic policy

Upon her accession to the throne, Elizaveta Petrovna, by a personal decree, abolished the Cabinet of Ministers and restored the Government Senate, “as it was under Peter the Great.” To consolidate the throne for her father's heirs, she summoned her nephew, the 14-year-old son of Anna's elder sister, Peter-Ulrich, Duke of Holstein, to Russia, and declared him her heir as Peter Fedorovich.

The empress transferred all executive and legislative power to the Senate, and she indulged in festivities: going to Moscow, she spent about two months in balls and carnivals, which ended with the coronation on April 25, 1742 in the Assumption Cathedral of the Kremlin.

Elizaveta Petrovna turned her reign into sheer entertainment, leaving behind 15 thousand dresses, several thousand pairs of shoes, hundreds of uncut pieces of fabric, the unfinished Winter Palace, which absorbed from 1755 to 1761. 10 million rubles. She wished to remodel the imperial residence to her taste, entrusting this task to the architect Rastrelli. In the spring of 1761, the construction of the building was completed, and interior work began. However, Elizaveta Petrovna died without ever moving to the Winter Palace. Construction of the Winter Palace was completed under Catherine II. This building of the Winter Palace has survived to this day.

Winter Palace, 19th century engraving

During the reign of Elizabeth Petrovna, no fundamental reforms were carried out in the state, but there were some innovations. In 1741, the government forgave the peasants' arrears for 17 years; in 1744, by order of the Empress, the death penalty was abolished in Russia. Homes for the disabled and almshouses were built. On the initiative of P.I. Shuvalov, a commission was organized to develop new legislation, noble and merchant banks were established, internal customs were destroyed and duties on foreign goods were increased, and conscription duties were eased.

The nobles again became a closed, privileged class, acquired by origin, and not by personal merit, as was the case under Peter I.

Under Empress Elizabeth Petrovna, the development of Russian science took off: M.V. Lomonosov published his scientific works, the Academy of Sciences published the first complete geographical atlas of Russia, the first chemical laboratory appeared, a university with two gymnasiums was founded in Moscow, and the Moskovskie Vedomosti began to be published. In 1756, the first Russian state theater was approved in St. Petersburg, of which A.P. became the director. Sumarokov.

V.G. Khudyakov "Portrait of I.I. Shuvalov"

The foundation of the library of Moscow University is being laid; it is based on books donated by I.I. Shuvalov. And he donated 104 paintings by Rubens, Rembrandt, Van Dyck, Poussin and other famous European artists to the collection of the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts. He made a huge contribution to the formation of the Hermitage art gallery. In Elizabethan times, art galleries became one of the elements of magnificent palace decoration, which was supposed to stun those invited to the court and testify to the power of the Russian state. By the middle of the 18th century, many interesting and valuable private collections appeared, the owners of which were representatives of the highest aristocracy, who, following the empress, sought to decorate palaces with works of art. The opportunity for Russian nobles to travel a lot and interact closely with European culture contributed to the formation of new aesthetic preferences of Russian collectors.

Foreign policy

During the reign of Elizaveta Petrovna, Russia significantly strengthened its international position. The war with Sweden, which began in 1741, ended with the conclusion of peace in Abo in 1743, according to which part of Finland was ceded to Russia. As a result of the sharp strengthening of Prussia and the threat to Russian possessions in the Baltic states, Russia, on the side of Austria and France, took part in Seven Years' War(1756-1763), which demonstrated the power of Russia, but cost the state very dearly and gave it practically nothing. In August 1760, Russian troops under the command of P.S. Saltykov defeated the Prussian army of Frederick II and entered Berlin. Only the death of Elizabeth saved the Prussian king from complete disaster. But Peter III, who ascended the throne after her death, was an admirer of Frederick II and returned all of Elizabeth’s conquests to Prussia.

Personal life

Elizaveta Petrovna, who in her youth was a passionate dancer and a brave rider, over the years found it increasingly difficult to accept the loss of her youth and beauty. From 1756, fainting and convulsions began to happen to her more and more often, which she carefully hid.

K. Prenne "Equestrian portrait of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna with her retinue"

K. Waliszewski, a Polish historian, writer and publicist, created a series of works dedicated to Russian history. Since 1892, he has published books in France in French, one after another, about the Russian tsars and emperors, and about their entourage. Walishevsky's books were united in the series “The Origin of Modern Russia” and cover the period between the reigns of Ivan the Terrible and Alexander I. In the book “Daughter of Peter the Great. Elizaveta Petrovna” (1902) he describes it this way Last year life of the empress: “Winter 1760-61. passed in St. Petersburg not so much in balls, but in tense anticipation of them. The Empress did not appear in public, locked herself in her bedroom, and received only ministers with reports without getting out of bed. For hours, Elizaveta Petrovna drank strong drinks, looked at fabrics, talked with gossips, and suddenly, when some outfit she tried on seemed successful to her, she announced her intention to appear at the ball. The court bustle began, but when the dress was put on, the empress’s hair was combed up and makeup was applied according to all the rules of art, Elizabeth went to the mirror, peered - and canceled the celebration.”

Elizaveta Petrovna was in a secret morganatic marriage with A.G. Razumovsky, from whom (according to some sources) they had children who bore the surname Tarakanov. In the 18th century Two women were known under this surname: Augusta, who, at the behest of Catherine II, was brought from Europe and tonsured into the Moscow Pavlovsk Monastery under the name Dosithea, and an unknown adventurer, who declared herself the daughter of Elizabeth in 1774 and laid claim to the Russian throne. She was arrested and imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress, where she died in 1775, hiding the secret of her origin even from the priest.

K. Flavitsky "Princess Tarakanova"

The artist K. Flavitsky used this story for the plot of his painting “Princess Tarakanova.” The canvas depicts a casemate of the Peter and Paul Fortress, outside of which a flood is raging. A young woman stands on the bed, trying to escape the water rushing through the barred window. The wet rats climb out of the water, approaching the prisoner's feet.

According to the testimony of contemporaries and historians, in particular, the Minister of Public Education Count Uvarov (the author of the formula Orthodoxy-Autocracy-Nationalism), Elizabeth was in a church morganatic marriage with Alexei Razumovsky. Even before her accession, Elizabeth began an affair with the Ukrainian singer A. G. Razumovsky, who received the title of count, orders, titles and large awards, but took almost no part in state affairs. Later, I.I. Shuvalov, who patronized education, became Elizabeth's favorite.

According to some historical sources from the 1770s - 1810s, she had at least two children: a son from Alexei Razumovsky and a daughter from Count Shuvalov.

Unknown artist Portrait of Alexey Grigorievich Razumovsky.

Louis Tokke Portrait of I.I. Shuvalov.

Subsequently, she took under her personal guardianship two sons and the daughter of chamber cadet Grigory Butakov, who were orphaned in 1743: Peter, Alexei and Praskovya. However, after the death of Elizaveta Petrovna, many impostors appeared, calling themselves her children from her marriage to Razumovsky. Among them, the most famous figure was the so-called Princess Tarakanova.

Georg Khristof Grooth Portrait of the Empress Elizaveta Petrovna in a Black Masquerade Domino. 1748

On November 7 (November 18), 1742, Elizabeth appointed her nephew (the son of her sister Anna), Duke of Holstein Karl-Peter Ulrich (Peter Fedorovich), as the official heir to the throne. His official title included the words “Grandson of Peter the Great.” Equally serious attention was paid to the continuation of the dynasty, to the choice of Peter Fedorovich’s wife (the future Catherine II) and to their son (the future Emperor Pavel Petrovich), whose initial education was given great importance.

Pietro Antonio Rotari Portrait of the Empress Elizabeth Petrovna. 1760

She died on December 25, 1761 in great suffering, but assured those around her that they were too small compared to her sins.

Peter III ascended the throne. The Empress was buried in the Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg. With the death of Elizabeth Petrovna, not only the line of Peter I, but also the entire Romanov dynasty was cut short. Although all subsequent heirs to the throne bore the Romanov surname, they were no longer Russian (Holstein-Gottorp line). The death of Elizaveta Petrovna also ended Russian participation in the Seven Years' War. The new emperor returned all the conquered lands to Frederick and even offered military assistance. Only a new palace coup and the accession to the throne of Catherine II prevented Russian military actions against former allies - Austria and Sweden.

Anna wrote to her sister from Kiel: “My dear Empress! I inform your Highness that, thank God, I came here in good health with the Duke, and it is very good to live here, because the people are very kind to me; only not a single day goes by that I don’t cry for you, my dear sister: I don’t know how you can live there. I ask you, dear sister, that you deign to write to me more often about the health of Your Highness.”

What should I write? Life was meager. It was believed that Elizabeth had her own court. Since 1724, Alexander Shuvalov was one of her pages. And the chamberlain was Semyon Grigorievich Naryshkin, a worthy and faithful man (let’s not forget that Elizabeth’s grandmother was Naryshkina). A handsome and generally clever man, Buturlin Alexander Borisovich (by the way, a holder of the Order of St. Alexander Nevsky, awarded by Father Peter I) was listed as her chamberlain at court. And the doctor was his own, smart and reliable Lestok. Under his father, he fell into disgrace and was exiled to Kazan, but after the death of his husband, Empress Catherine returned him and assigned him to her daughter’s court. But life is dull, nothing, they give little money for maintenance, and Elizabeth is used to living generously.

Peter II was eleven years old. Catherine did not appoint a guardian for him, entrusting the duties of guardianship to the Supreme Council. It was unanimously accepted that the boy emperor came of age at 16 years old. Menshikov was very active. He declared himself a generalissimo and stood at the head of the Russian army. He was truly omnipotent. Under the guise of guardianship, he took the emperor to his palace on Vasilievsky Island and betrothed him to his daughter Maria. Now Peter lived under constant surveillance. Menshikov did not let him leave him even one step.

But the young sovereign did not tolerate this for long. He had a decisive and willful character. He did not like to study, but he was a great lover of games, and most of all he loved hunting. Few people are committed to science at the age of eleven; it was impossible to predict what they would be like in adulthood. He lost his parents in infancy, spent his childhood under someone else's care and was truly attached only to his sister Natalya Alekseevna. She was only a year older than her brother, but already had her own court with the chamberlain, Prince Alexei Petrovich Dolgoruky. The prince's son, Ivan Dolgoruky, became very close with the young tsar and played a fatal role in his life.

Menshikov entrusted the education of the young tsar to Vice-Chancellor Osterman, whom he trusted infinitely. But in vain. Osterman was a smart politician, an excellent intriguer and a very cautious person. He set a goal for himself and walked towards it carefully, slowly, and always achieved his goal. Osterman was tired of living under Menshikov’s heel, so he set a goal for himself. He decided, with the help of Peter II, to overthrow the temporary worker from his pedestal and carry out his earlier plan - to marry Peter to his aunt Elizabeth.

Menshikov's constant guardianship was a burden to Peter II. As soon as he realized his importance, he immediately asked himself the question: by what right does the temporary worker dispose of everything and keep him in a cage? When Tsarevich Alexei was executed in 1718, Peter II was only a year old. We don’t know who and when told the boy about the torment and death of his father, but at the age of twelve he was aware of a lot. He had reason to hate his imaginary benefactor.

And suddenly Menshikov fell ill, seriously and for a long time. Documents mention hemoptysis and fever. He was so bad that he was about to die. It was here that Peter slipped out of the palace on Vasilyevsky Island. A young company formed spontaneously: the Tsar himself, his sister Natalya, nicknamed “Minerva” for her intelligence and restraint, Ivan Dolgoruky, as well as pages and gentlemen. The soul of the whole company was Elizabeth, the nickname “Venus” suited her very well.

CM. Solovyov writes: “Elizabeth Petrovna was 17 years old; she caught everyone's gaze with her slenderness, round, extremely pretty face, blue eyes, and beautiful complexion; cheerful, lively, carefree, which distinguished her from her serious sister Anna Petrovna, Elizaveta was the soul of a young society that wanted to have fun; there was no end to the laughter when Elizabeth began to introduce someone, which she was an expert at; It also went to people close to him, for example, to the husband of his elder sister, the Duke of Holstein. It is not known whether three heavy blows - the death of the mother, the death of the groom and the departure of the sister - cast a shadow over Elizabeth's cheerful being for a long time; at least we see her as a companion of Peter II on his joyful walks and meet the news of his strong affection for her.”

Yes, Peter fell in love with his aunt. Twelve years old, by our standards, is sixth grade, but in the 18th century they grew up early. Peter fell in love, and Osterman helped him a lot with this. The latter had a wonderful relationship with Natalya Alekseevna: Andrei Ivanovich is kind, smart, and generous. Natalya knew how to persuade her brother, saying that if you listen to someone and trust someone, then this person is Osterman.

Menshikov recovered and wished to return the power that had slipped away, but that was not the case. He did not recognize the king. Disagreements have happened before, and all because of such a trifle as money. Did the temporary worker need to think about this? A workshop of St. Petersburg masons presented Peter II with 9,000 rubles. Peter accepted them and sent them to his sister. On the way, Menshikov intercepted the courier and took the money. The Tsar demanded, indeed demanded, an explanation. “You, Your Majesty, are still too young and do not know how to handle money, and the treasury is empty, I will find a better use for this money.” Peter flared up: “How dare you disobey my orders?” Menshikov was literally dumbfounded by such determination; he did not expect anything like this. He should have learned his lesson, but an incident similar to the previous one was repeated, and again money, and again sister Natalya, and an even more severe reprimand from Peter. Feeling the strength of the sovereign, they began to turn to him with requests, and now Peter was resolving the dispute in army affairs. Finally the phrase was thrown: “Either I am the emperor, or he!” There was no turning back.

Menshikov’s “dominion” under the young tsar lasted four months, and then arrest, confiscation of property, exile, Berezov, death. The reason for this was, of course, the intrigues of Osterman and the Dolgoruky clan, who had their own plans for Peter, but Menshikov cannot absolve himself of his guilt. He swung too decisively, lost his vigilance and completely did not take into account the character of his charge.

Elizabeth also took an indirect part in the fall of the illustrious prince. Peter was in love with her, and another wife was forced on him. The Tsar did not like Maria Menshikova. Hearing that Menshikov was complaining that he was not paying any attention to the bride, Peter said: “Isn’t it enough that I love her in my heart; caresses are unnecessary; As for the wedding, Menshikov knows that I do not intend to get married before 25 years.”

On September 3, 1727, Menshikov organized a great celebration in Oranienbaum on the occasion of the consecration of the church. It was very important for him that Peter be there. Relations with the emperor became extremely strained. Menshikov inundated Peter with written and oral requests - if only he would appear at the celebration, showing by this that everything was getting better. Peter did not come, citing the fact that Menshikov forgot to invite Elizabeth to the celebration.

Menshikov was not lazy and the next day or so galloped to Peterhof, where Elizabeth’s name day was to be celebrated. He hoped to see and talk with Peter, but he was already getting ready to hunt. Sister Natalya, having learned about Menshikov’s arrival, jumped out the window and hurried after her brother - just to avoid meeting the temporary worker. Menshikov went so far as to complain to Elizabeth, this frivolous girl whom he did not even take into account, about Peter’s ingratitude. He did everything for the emperor, and this one, and that one... On September 8, Menshikov was arrested. History, as they say, has turned the page.

The fall of Menshikov was accepted by everyone with delight. They talked about his terrible abuses, about arbitrariness, about theft, moreover, this temporary worker “stretched out his hands to the crown.” A regrouping took place at court and several parties were formed. None of the nobles “stretched out their hands to the crown,” but everyone longed to gain a profitable place, and title, and power, and it seemed that the current time was very conducive to this, just show up and be persistent.

At the end of 1728, the court went to Moscow. Formally, we were going to the coronation, and it never occurred to anyone that life in the old capital would drag on for years. In Moscow, the Dolgorukies immediately perked up. Prince Alexei, the chamberlain at the court of Natalya Alekseevna, begged for a position as the Tsar's assistant tutor; now he had the opportunity to see Peter very often, and therefore influence him. Son Ivan Alekseevich received the rank of chief chamberlain and the Order of St. Andrew, he was already openly called Peter’s favorite.

Elizabeth is still in great favor with the emperor. With her assistance, a new person appeared at his court - Count Buturlin Alexander Borisovich. He was treated kindly by Peter II, promoted to general and appointed ensign in the cavalry corps. They said that Buturlin would reconcile all parties at court. And there were many parties. Peter's arrival in Moscow was perceived by many as a rejection of the policies of Peter the Great and a return to antiquity. The old capital perceived the executed father of the emperor, Alexei, as a martyr, and now pinned great hopes on his son.

In Moscow, Peter met his grandmother Evdokia Fedorovna Lopukhina - she lived in the Novodevichy Convent, although she was not tonsured. Much was expected from this meeting; it could determine the future policy of the state. But the meeting between the royal grandson and grandmother turned out to be cold; Peter was afraid of further moralizing. In addition to his sister Natalya, he took Elizaveta with him to the meeting, immediately emphasizing that he was quite friendly with his aunt and would not tolerate unnecessary conversations. At that moment, the crown princess was both his friend and adviser. But soon everything changed.

Many people wanted to push Elizabeth away from the emperor. Sister Natalya was desperately jealous of her brother. She was very ill, doctors found that she had consumption, but other rumors circulated at court. The Spanish envoy to the Russian court, Duke de Liria, who left very valuable “Notes,” writes: “But consumption was not the cause of her illness, and only one doctor could cure her, namely her brother. Upon his accession to the throne, His Majesty had such confidence in his sister that he did everything for her and could not remain without her for a minute. They lived in the greatest harmony, and the Grand Duchess gave amazing advice to her brother, although she was only one year older than him. Little by little, however, the king became attached to his aunt, Princess Elizabeth, and his favorite and other courtiers, who did not like the Grand Duchess because she respected Osterman and favored foreigners, tried in every possible way to praise the princess, who did not love her niece, and they did so that after six months the king no longer spoke to her about any matters and, therefore, no longer had any confidence in her.”

Who are these people “who did not love the Grand Duchess”? In Moscow, Peter II again found himself “in captivity.” If in St. Petersburg this captivity was the house on Vasilievsky Island, then in Moscow this place became the Gorenki estate. Menshikov protected the tsar from foreign influence with orders and force, but now the favorite Ivan Dolgoruky, his father Alexei Grigorievich and their entire clan surrounded him with such love that they could strangle him in their arms, which, by the way, they succeeded. Considering their own benefit everywhere, the Dolgorukys acted very smartly and carefully. Favorite Ivan, handsome, cheerful, immoral and tireless in amorous affairs, became the Tsar's closest and irreplaceable friend. Alexey Grigorievich Dolgoruky was always ready to fulfill any whim of the boy-tsar, emphasizing at the same time that he was a loyal subject and could not contradict him in anything. But Peter still did not want to study, state affairs interested him little, he loved hunting, which turned into an endless journey and short rests (or maybe orgies) in Gorenki.

There was a person who summarized the statistics of state hunting. During nearly two years of Peter's stay in Moscow, 243 days were devoted to hunting. A huge departure of five hundred carriages - nobles, servants, huntsmen, cooks - followed the king. During the day they chased hares and foxes through the forests and valleys with dogs, and in the evening they set up camp and had a large feast.

Elizabeth loved hunting, she also rode horseback around the province, but life did not promise her anything good. A month after we moved to Moscow, a message arrived from Kiel - a son was born to our beloved sister Anna Petrovna. Vivat, vivat, hurray! Fireworks, cannon fire, a ball, Elizabeth shone at it. But already in May, bitter news came from Holstein about the death of her sister. In Kiel, the birth of the heir was also widely celebrated, and there were also fireworks. Anna admired him, standing at the open window. It was cold, damp, the courtiers begged her to close the window, but the duchess only laughed: we Russians don’t care! But she caught a bad cold, then a fever began, followed by death.

Here again there was talk about Elizabeth's marriage. Foreign princes applied for her hand, even the old Duke Ferdinand of Courland decided to try his luck. Elizabeth refused everyone. We decided to look for the groom at home. One of the observant nobles rendered a verdict: Ivan Dolgoruky is clearly in love with Elizabeth, why not marry them? Ivan may have dragged himself after the beautiful Elizabeth, but this is not yet a reason to get married. And these conversations could only begin with the consent of Peter II. Apparently, they hoped to obtain this consent, because the king had already begun to cool off towards his aunt. Then the question of Elizabeth’s marriage naturally disappeared. Elizaveta moved away from the court and lived mostly in Pokrovskoye, sometimes going to Izmailovo to visit her sister Ekaterina Ivanovna. Catherine of Mecklenburg had little interest in state affairs - she did housework, embroidered church clothes and parsuns. And then suddenly Elizabeth moved to Alexandrovskaya Sloboda, the former possession of her mother, and lived there, enjoying complete freedom. The most harmful rumors circulated about her reputation in Moscow.

De Liria writes: “September 16th is Princess Elizabeth’s name day. Her Highness invited us to her palace at 4 pm for dinner and dancing. The Tsar did not arrive until just before dinner, and as soon as it was over, he left without waiting for the ball, which I opened with the Grand Duchess. Never before had he so clearly shown his displeasure towards the princess, which made her very annoyed, but she, as if not noticing this, showed a cheerful appearance all night.”

Meanwhile, Natalya Alekseevna was living out her last days. The doctors decided to resort to a last resort - they gave her breast milk. For a moment this helped, but then she got worse and died in November 1728. The cabinet decided that this was a sign: now it would certainly be possible to persuade the emperor to return to St. Petersburg and get down to business. The Tsar was present at his deathbed, he was very sad, but then he took off again. The Dolgorukys grabbed him by the arms and took him to Gorenki. What better way to dispel sorrow than hunting?

It's time to explain the reason for Peter's cooling towards his aunt. Waliszewski writes that Elizabeth “missed her chance to become empress.” Now she missed it, then this “chance” fell into her hands. And in general, what can we talk about if she was in love - at twenty years old this is the most important thing in the world. The object of her love was the chamberlain of her court, and now also the tsar’s favorite, Alexander Buturlin. I’ll tell you especially about this man; it’s not for nothing that a large article is dedicated to him in the Brockhaus and Efron encyclopedia.

So, 1729. In March, on the day of the king’s accession to the throne, there was a congress to the court to kiss the hand. Orders and awards were distributed there, followed by a ball and dinner. Elizabeth was not at the convention or at the ball. De Liria writes that she said she was sick, but recovered the next day, about which there was a lot of talk.

And in Moscow they were already openly talking about Alexei Dolgorukov’s intention to marry the Tsar to his eldest daughter Catherine. She was a beauty, brown eyes, black hair, blood and milk. Catherine was older than Peter, she already had a beloved Count Melekzino, the Austrian ambassador. Peter was not in love with his bride, but he could not refuse her marriage. It was under Menshikov that he could allow himself to stamp his foot, and the Dolgorukys tied his hands with their “love.” They tortured Peter with endless hunting, drunkenness, gluttony and an unhealthy lifestyle. And he was tired of hunting, tired of being a toy in the wrong hands. He was quite tired of the Dolgorukies, but the shackles were too strong. It was especially difficult to realize that Peter forged them for himself. Everything was arranged in such a way that the sovereign himself chose his bride. They had arranged a meeting in private in advance, and now, according to all divine and human laws, he was obliged to marry her.

On November 30, 1729, the betrothal took place in the Lefortovo Palace. Princess Elizabeth, among other relatives, attended the ceremony. After the engagement, Peter seemed to come to his senses, met with Osterman - apparently, asked for advice. While Osterman could not cope with the Dolgorukys, he did not impose himself as an adviser, he had no time for that - he was sick. Once Peter secretly saw Elizabeth. There is information that the Dolgorukys, fearing the influence of the crown princess, already had a plan to exile her to a monastery.

A few preliminary words about Andrei Ivanovich Osterman, a German from Bochum. He had been in Russian service since 1703, and later actually stood at the head of Russian foreign and domestic policy. Osterman was a magnificent and cunning politician; it was not for nothing that he outlived so many sovereigns. At a dangerous moment, he fell ill: colic, gout, and bad teeth, at worst, were used. As soon as the political horizon became clear, the sufferer immediately felt better and began to fulfill his duties. Using this weather vane, the yard often guessed which way the wind was blowing: since Osterman got sick, then don’t stick your nose out either. At court Osterman had the nickname “Oracle”.

The wedding was scheduled for January 19, 1730, but it was not destined to take place. Exhausted, devastated, tired, the boy-king caught a cold and fell ill; the cold was followed by smallpox - the scourge of that time. Osterman was present at his bedside all the time, the king raved about his name. Here is his last phrase (these “last phrases” are always exciting): “Harness the sleigh! I’m going to my sister!” The death of Peter II fell precisely on January 19, 1730.

- Russian Empress (1741-24 December 1761), daughter of Peter the Great and Catherine I (born December 18, 1709). Since the death of Catherine I, Grand Duchess Elizaveta Petrovna went through a hard school. Her position was especially dangerous under Anna Ioannovna and Anna Leopoldovna, who were constantly frightened by the guard's commitment to Elizabeth. She was saved from becoming a nun by the existence abroad of her nephew, the Prince of Holstein; during his lifetime, any drastic measure with Elizabeth would have been useless cruelty. Foreign diplomats, the French ambassador Chetardie and the Swedish Baron Nolken, decided, from the political views of their courts, to take advantage of the mood of the guard and elevate Elizabeth to the throne. The mediator between the ambassadors and Elizabeth was the physician Lestocq. But Elizabeth managed without their assistance. The Swedes declared war on the government of Anna Leopoldovna, under the pretext of liberating Russia from the yoke of foreigners. The guard regiments were ordered to set out on a campaign. Before the performance, the soldiers of the grenadier company of the Preobrazhensky Regiment, most of whom Elizabeth baptized children, expressed concern to her: would she be safe among the enemies? Elizabeth decided to act. At 2 a.m. on November 25, 1741, Elizabeth appeared at the barracks of the Preobrazhensky Regiment and, reminding whose daughter she was, ordered the soldiers to follow her, forbidding them to use weapons, because the soldiers threatened to kill everyone. A coup took place at night, and on November 25 a short manifesto was issued on Elizabeth’s accession to the throne, drawn up in very vague terms. Not a word was said about the illegality of Ivan Antonovich’s rights. In front of the guards, Elizabeth showed great tenderness towards John. A detailed manifesto dated November 28 was written in a completely different tone, recalling the order of succession to the throne established by Catherine I and approved by the general oath (see Catherine I). The manifesto says that the throne, after the death of Peter II, followed Elizabeth. Its compilers forgot that, according to Catherine’s will, after the death of Peter II, the throne was to go to the son of Anna Petrovna and the Duke of Holstein, born in 1728. In the accusations directed against the German temporary workers and their friends, they were accused of many things, including what they were not guilty of: this is explained by the fact that Elizaveta Petrovna was very irritated by the attitude towards her of people exalted by her father - Minikh, Osterman and others. Public opinion did not think, however, to enter into an analysis of the degree of guilt of certain persons; The irritation against the German temporary workers was so strong that the cruel execution they determined was seen as retribution for the painful execution of Dolgoruky and Volynsky. Osterman and Minich were given the death penalty by quartering; Levenvold, Mengden, Golovkin - simply the death penalty. The death penalty has been replaced by exile for everyone. It is remarkable that Minich was also accused of appointing Biron as regent, but Biron himself was not only left untouched, but his fate was even made easier: he was transferred from Pelym to his place of residence in Yaroslavl (since Biron himself did not push Elizabeth).

Empress Elizaveta Petrovna. Portrait by I. Vishnyakov, 1743

In the first years of Elizabeth's reign, conspiracies were constantly being discovered; This is where, by the way, the grim case of the Lopukhins arose. Cases similar to Lopukhin's arose from two reasons: 1) from exaggerated fear of adherents of the Brunswick dynasty, the number of which was extremely limited, and 2) from the intrigues of persons who were close to Elizaveta Petrovna, for example, from the undermining of Lestocq and others against Bestuzhev-Ryumin. Lestok was a supporter of an alliance with France, Bestuzhev-Ryumin - an alliance with Austria; Therefore, foreign diplomats intervened in the domestic intrigue. Natalya Fedorovna Lopukhina, the wife of the lieutenant general, was famous for her outstanding beauty, education and courtesy. They said that under Anna Ioannovna, at court balls, she overshadowed Elizaveta Petrovna, and that this rivalry instilled in Elizaveta Petrovna enmity towards Lopukhina, who at that time already had a son, an officer. She was friends with Anna Gavrilovna Bestuzheva-Ryumina, née Golovkina, the wife of the vice-chancellor's brother. Lopukhina, who was in connection with Levenvold, sent him a bow with one officer, telling him not to lose heart and hope for better times, and Bestuzheva sent a bow to her brother, Count Golovkin, also exiled in the so-called case of Osterman and Minich. Both were acquainted with the Marquis Botta, the Austrian envoy in St. Petersburg. Botta, without hesitation, expressed to his female acquaintances the unfounded assumption that the Brunswick dynasty would soon reign again. Transferred to Berlin, he repeated the same assumptions there. All this empty chatter gave Lestocq a reason to concoct a conspiracy through which he wanted to strike at Vice-Chancellor Bestuzhev-Ryumin, the defender of the Austrian union. The investigation of the case was entrusted to the Prosecutor General Prince Trubetskoy, Lestok and Chief General Ushakov. Trubetskoy hated Bestuzhev-Ryumin as much as Lestok, but he hated Lestok himself even more; he belonged to the oligarchic party, which, after the overthrow of the German temporary workers, hoped to seize power into its own hands and resume the attempt of the supreme leaders. From people who did not hide their regret for the exiled, it was easy to get confession in daring speeches against the empress and in censure of her privacy. Torture was used in the case - and despite all this, only eight people were brought to trial. The sentence was terrible: Lopukhin, her husband and son, having their tongues cut out, were to be driven on the wheel. Elizaveta Petrovna abolished the death penalty: Lopukhin, her husband and son, after cutting out their tongues, were ordered to be beaten with a whip, others - only to be beaten with a whip. The manifesto, in which Russia was notified of the Lopukhins’ case, again spoke of the illegality of the previous reign. All this caused sharp criticism against Elizabeth and did not bring the result desired by the intrigue - the overthrow of the Bestuzhevs. The importance of the vice-chancellor not only has not decreased, but has even increased; after some time he received the rank of chancellor. Shortly before the start of the Lopukhina case, Bestuzhev stood for the dismissal of Anna Leopoldovna, with her family, abroad; but the Lopukhins’ case and Anna Leopoldovna’s refusal to renounce, for her children, her rights to the Russian throne were the reason for the sad fate of the Brunswick family (see Anna Leopoldovna). To calm minds, Elizabeth hastened to summon her nephew Karl-Peter-Ulrich, the son of Anna Petrovna and the Duke of Holstein, to St. Petersburg. On November 7, 1742, just before the announcement of the Lopukhins’ case, he was proclaimed heir to the throne. Before that, he converted to Orthodoxy and in church proclamations in his name it was ordered to add: grandson of Peter the Great.

Having secured power for herself, Elizabeth hastened to reward the people who contributed to her accession to the throne or were generally loyal to her. The grenadier company of the Preobrazhensky regiment received the name of the life campaign. Soldiers not from the nobility are enrolled as nobles; they were given estates. Company officers were equal to the ranks of generals, Razumovsky and Vorontsov were appointed lieutenants, with the rank of lieutenant general, the Shuvalovs were appointed second lieutenants, with the rank of major generals. Sergeants became colonels, corporals became captains. The riot of soldiers in the first days of Elizabeth's accession to the throne reached extremes and caused bloody clashes. Alexey Razumovsky, the son of a simple Cossack, showered with orders, in 1744 was already a count of the Roman Empire and the morganatic husband of Elizabeth. His brother Kirill was appointed president of the Academy of Sciences and hetman of Little Russia. Lestocq, who had worked so hard for Elizabeth, was granted the title of count. At the same time, the rise of the Shuvalov brothers, Alexander and Pyotr Ivanovich, with their cousin Ivan Ivanovich began. The chief of the secret chancellery, Alexander Ivanovich, enjoyed the greatest confidence of Elizaveta Petrovna. He left behind the most hateful memory. The Shuvalovs were followed by Vorontsov, who was appointed vice-chancellor, after the appointment of Count Bestuzhev-Ryumin as chancellor. Before the Seven Years' War, the strongest influence was enjoyed by Chancellor Bestuzhev-Ryumin, whom Lestocq wanted to destroy, but who himself destroyed Lestocq. He deciphered the letters of the French ambassador Chetardy, a friend of Lestocq, and found harsh expressions about Elizabeth Petrovna in the letters. Lestocq's estates were confiscated, and he was exiled to Ustyug.

In foreign policy, Bestuzhev knew how to put Russia in such a position that all powers sought its union. Frederick II says that Bestuzhev took money from foreign courts; this is likely, because all of Elizabeth’s advisers took the money - some from Sweden, some from Denmark, some from France, some from England, some from Austria or Prussia. Everyone knew this, but they were silent about this sensitive issue until, as over Lestocq, a thunderstorm broke out on some other occasion. When Elizabeth Petrovna ascended the throne, peace with Sweden could have been expected; but the Swedish government demanded the return of the conquests of Peter the Great, which led to the resumption of the war. The Swedes were defeated and around the world in Abo, in 1743, they had to make new territorial concessions to Russia (part of Finland, along the Kyumen River). In the same year, the question of succession to the throne in Sweden, which had been shaking this country since 1741, since the death of Ulrich-Eleonora, was resolved. On the advice of Bestuzhev, armed assistance was sent to the Holstein party and Adolf-Friedrich, the uncle of the heir to Elizabeth Petrovna, was declared heir to the throne. The War of the Austrian Succession was also ended with the assistance of Russia. England, an ally of Austria, being unable to keep the Austrian Netherlands behind its ally, asked for help from Russia. The appearance of a corps of Russian troops on the banks of the Rhine River helped end the war and conclude the Peace of Aachen (1748). The influence of the chancellor was increasing; Elizaveta Petrovna took his side even in his dispute with the heir to the throne on the issue of Schleswig, which the Grand Duke wanted, contrary to the will of the Empress, to keep for his home. In the future, this discord threatened Bestuzhev-Ryumin with troubles, but he then managed to attract Grand Duchess Ekaterina Alekseevna to his side. Only during the Seven Years' War did the enemies of the chancellor finally manage to break him (see the Seven Years' War and Bestuzhev-Ryumin). The chancellor was put on trial, he was stripped of his ranks and exiled.

Important deeds were accomplished under Elizabeth on the outskirts of Russia; a very dangerous fire could break out there at the same time. In Little Russia, the management of the Little Russian Collegium left behind terrible displeasure. Elizaveta Petrovna, visiting Kyiv in 1744, calmed the region and allowed the election of a hetman in the person of her favorite brother, Kirill Razumovsky. But Razumovsky himself understood that the time of hetmanship was over. At his request, cases from the Little Russian Collegium were transferred to the Senate, on which the city of Kyiv directly depended. The end was approaching for Zaporozhye (see this word and Catherine II), for the steppes, since the time of Anna Ioannovna, were populated more and more. During the reign of Elizabeth Petrovna, new settlers were called; in 1750, in the current districts of Alexandria and Bobrinetsky, Kherson province, Serbs were settled, from whom two hussar regiments were formed. These settlements are called New Serbia. Later, in the current Ekaterinoslav province, in the districts of Slavyanoserbsky and Bakhmutsky, new Serbian settlers settled (Slavyanoserbia). Near the fortress of St. Elizabeth, on the upper reaches of the Ingul, formed settlements from Polish immigrants, Little Russians, Moldavians and schismatics, which gave rise to the Novoslobodskaya line. Thus, Zaporozhye was constrained from almost all sides by the already emerging second Novorossiya. In the first New Russia, that is, in the Orenburg region, in 1744, as a result of serious unrest of the Bashkirs, the Orenburg province was established, the governor of which was subordinate to the Ufa province and the Stavropol district of the current Samara province. Neplyuev was appointed governor of Orenburg. He caught the Bashkir rebellion; the Bashkirs could easily unite with other foreigners; Neplyuev had few troops - but he raised the Kirghiz, Teptyars, Meshcheryaks against the Bashkirs, and the rebellion was pacified. He was helped a lot by the fact that, due to the small number of Russian elements in the region, factories under Anna Ioannovna were built there as fortresses. The general displeasure and irritation of foreigners also affected the remote northeast: the Chukchi and Koryaks in Okhotsk threatened the Russian population with extermination. The Koryaks, holed up in a wooden fort, were especially cruel: they burned themselves voluntarily rather than surrender to the Russians.

Empress Elizaveta Petrovna. Portrait by V. Eriksen

A few weeks after her accession to the throne, Elizabeth issued a personal decree that the Empress saw a violation of order government controlled, established by her parent: “through the machinations of some (individuals), the Supreme Privy Council was invented, then a cabinet was created in equal strength, as there was a Supreme Privy Council, only the name was changed, which resulted in a lot of omissions, and justice became completely weak.” Under Elizabeth, the Senate gained strength such as it had never had before or since. The number of senators was increased. The Senate stopped the flagrant disorder both in the colleges and in the provincial institutions. The Arkhangelsk prosecutor, for example, reported that secretaries go to office whenever they want, which is why convicts are kept for a long time. The Senate rendered a particularly important service in one of the years when the poor people in Moscow were in danger of being left without salt. Thanks to the stewardship of the Senate, salt was delivered and the salt tax, one of the important revenues of the treasury, was put in order. Since 1747, when Elton salt was discovered, the salt issue has not become aggravated to such an extent. In 1754, at the suggestion of Pyotr Ivanovich Shuvalov, internal customs and outposts were abolished. According to S. M. Solovyov, this act completed the unification of eastern Russia, destroying traces of appanage division. According to the projects of the same Shuvalov: 1) Russia, in order to ease the burden of recruitment, was divided into 5 stripes; in each strip, recruitment occurred every 5 years; 2) commercial and noble banks were established. But Shuvalov’s merits were not understood by everyone, and the results of his greed were obvious to everyone. He turned sealing and fishing in the White and Caspian Seas into his monopoly; In charge of the alteration of copper coins, he privately gave away money at interest. The Razumovskys, the closest people to Elizaveta Petrovna, did not intervene in state affairs; their influence was great only in the field of church administration. Both Razumovskys were imbued with boundless respect for the memory of Stefan Yavorsky and hostility towards the memory of Feofan Prokopovich. Therefore, people who hated Prokopovich’s educational aspirations began to be elevated to the highest levels of the hierarchy. The very marriage of Elizabeth with Razumovsky was suggested by her confessor. The liberation of Russia from German temporary workers, aggravating the already strong spirit religious intolerance has cost Russia dearly. Sermons in this direction did not spare not only the Germans, but also European science. In Minich and Osterman they saw emissaries of Satan, sent to destroy the Orthodox faith. The abbot of the Sviyazhsk monastery, Dimitri Sechenov, called his opponents the prophets of the Antichrist, who forced the preachers of Christ's word to remain silent. Ambrose Yushkevich accused the Germans of deliberately slowing down the progress of education in Russia and persecuting the Russian students of Peter the Great - a weighty accusation, supported by Lomonosov, who, however, equally accused German academicians and the clergy of the same obscurantism. Having got censorship in its hands, the synod began by submitting a decree for signature in 1743 prohibiting the import of books into Russia without prior inspection. Chancellor Count Bestuzhev-Ryumin rebelled against the draft of this decree. He convinced Elizabeth that not only the ban, but also the delay of foreign books by censorship would have a harmful effect on education. He advised to exempt historical and philosophical books from censorship, and to review only theological books. But the chancellor's advice did not stop the jealousy of the book ban. Thus, Fontenelle’s book “On the Many Worlds” was banned. In 1749, it was ordered to select a book printed under Peter the Great - “Pheatron, or Historical Shame”, translated by Gabriel Buzhansky. In the church itself, phenomena were discovered that pointed to the need for broader education for the clergy themselves: when fanatical self-immolations intensified among schismatics, our shepherds were unable to stop the wild manifestations of fanaticism with a word and appealed to the secular authorities for help. But representatives of the clergy even took up arms against church schools. Arkhangelsk Archbishop Barsanuphius expressed displeasure at the large school built in Arkhangelsk: schools were loved by the bishops of Cherkassy, i.e. Little Russians. It is not surprising that people of this way of thinking had to deal with the Senate in state and legislative matters. Elizaveta Petrovna, due to her personal character, significantly softened our criminal legislation, abolishing the death penalty, as well as torture in tavern cases. The Senate presented a report so that minors under seventeen years of age were completely exempt from torture. The Synod here also rebelled against mitigation, arguing that childhood, according to the teachings of St. fathers are considered only up to 12 years of age. At the same time, it was forgotten that the decrees to which the synod referred were issued for southern countries, where girls begin puberty at the age of 11-12. At the beginning of Elizabeth's reign, Prince Yakov Petrovich Shakhovskoy, a one-sided, proud, but honest man, was appointed chief prosecutor to the synod. He demanded regulations, instructions to the chief prosecutor and a register of unresolved cases; Only the regulations were delivered to him; the instructions were lost and only then delivered to him by the Prosecutor General, Prince Trubetskoy. Fines were ordered for talking in church. The fine was collected by officers who lived at the monasteries; The synod began to prove that the collection of fines should be carried out by the clergy. Such bickering most clearly indicated the need for education. But, with a general almost hatred of enlightenment, powerful energy was required to defend its necessity. Therefore, the memory of Ivan Ivanovich Shuvalov and Lomonosov, who connected their names with the most useful work of the reign of Elizabeth Petrovna, is worthy of the deepest respect. According to their project, in 1755, the Moscow University was founded, gymnasiums arose in Moscow and Kazan, and then the Academy of Arts was founded in St. Petersburg.

By her personal character, Elizabeth was alien to political ambition; it is very likely that if she had not been persecuted under Anna Ioannovna, she would not have thought about a political role. In her youth, she was only interested in dancing, and in her old age - the pleasures of the table. Her love of far niente [doing nothing] grew stronger every year. So, for two years she could not get ready to answer the letter from the French king.

Sources: P.S.Z.; memoirs; The notes of Prince Shakhovsky, Bolotov, Dashkov and others are especially important. The history of Elizabeth is described in detail by S. M. Solovyov. The sketch of the reign of Empress Elizabeth also deserves attention. Eshevsky.

All of England is preparing for the marriage of the heir to the English throne, Prince William. It is impossible for us to ignore this joyful event. Wonderful couple. The young heirs are young, beautiful, happy, full of hope. The celebration continues, the dynasty continues, and with it, Prince William's rich dynastic legacy continues. Through his grandfather Philip of Edinburgh, the young heir to the British throne is a descendant of Russian emperors, as well as the kings of Prussia, Denmark, and Greece. To be precise, Prince William of England is a great-great-great-great-grandson Russian Emperor Nicholas I, great-great-great-great-grandson of the Prussian king Frederick William III, great-great-great-grandson of the Danish king Christian IX, great-great-grandson of the Greek king George I. Of course, no longer exists Russian Empire, Prussia, and with them the dynasty ceased to exist, the kingdom of Greece no longer exists. But the story remains. And we return to it, but only to its “Russian part”, to the Russian roots of the British kings.

NikolayI, Emperor of All Russia, Tsar of Poland and Grand Duke of Finland. Grandson Great Catherine II, son of the unfortunate Emperor Paul, younger brother of Emperor Alexander I the Blessed, great-great-great-great-grandfather of Prince William . Terrible Emperor. Some authors call Nicholas a “knight of autocracy”; he firmly defended its foundations. After the Decembrist uprising in 1825, which overshadowed his accession to the throne, he launched measures in the country to eradicate the “revolutionary infection”, founding a secret police to monitor the state of minds in the state. He fought against any manifestations of change in European life. In 1830, Nicholas pacified the Polish national liberation uprising directed against the Russian Empire. At the request of Austria in 1849, Russia took part in the suppression of the Hungarian revolution, sending 140 thousand soldiers to Hungary for this purpose. It was under Nicholas I that Russia earned the unflattering nickname of “the gendarme of Europe.” By the end of his reign, he fell out with all of Europe, as a result of which Russia remained isolated in the Crimean War.

Wife of Nicholas I Alexandra Fedorovna(nee Princess Frederica Charlotte Wilhelmina of Prussia) - daughter of the Prussian king, Napoleon's conqueror, Frederick William III and his wife, Queen Louise, sister of the Prussian kings Frederick William IV and Wilhelm I, who later became the first emperor of a united Germany, great-great-great-great-grandmother of Prince William. Despite the fact that this marriage was concluded for political reasons in order to consolidate the alliance of Russia and Prussia, the married life of Nikolai and Alexandra was very successful.

Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich- second son of Emperor Nicholas I and Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, great-great-great-grandfather of Prince William. From him came the branch of the Konstantinovich Romanov family. Thus, future English kings will be descendants of this branch of the Romanov dynasty. Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich is a bright personality of the House of Romanov. A reformer and liberal, he played a major role in the reforms of his brother Emperor Alexander II. As an admiral of the fleet and minister of the maritime department, he transformed the Russian fleet from obsolete into a modern armored and steam-powered one. He was chairman of the State Council of the Empire. It was on his initiative that Russian Alaska was sold to America in 1867. He married out of passionate love his second cousin Alexandra of Saxe-Altenburg, who became a Grand Duchess in Orthodoxy Alexandra Iosifovna, future great-great-great-grandmother of Prince William. In this marriage, the future Greek queen was born - Grand Duchess Olga Konstantinovna, grandmother of Philip of Edinburgh (husband of Elizabeth II).

Grand Duchess Olga Konstantinovna- daughter of Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich, niece of Emperor Alexander II, granddaughter of Nicholas I. In 1867, her wedding took place in St. Petersburg with the king of Greece. This marriage is a success for Russian diplomacy, because... he strengthened diplomatic relations between Greece and Russia and brought closer the reigning houses of Russia, Greece and Denmark. In addition, this marriage strengthened Russian positions in the Mediterranean region, which was extremely important in the context of a constant military conflict with Turkey. The Queen was involved in charity work and founded a naval hospital in Piraeus, where the Russian navy base was located. Since the beginning of the First World War, she came to Russia and worked in hospitals, helping the wounded.

Her husband, the Greek king George I by birth - Danish Prince Christian Wilhelm Ferdinand Adolf Georg of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg. He was the second son of King Christian XI of Denmark and his wife Louise of Hesse-Kasel. On March 30, 1863, through the efforts of Russia, Great Britain and France, he was elected and ascended to the Greek throne under the name of George at the age of 17. The Greek royal family was closely related to the British and Russian dynasties. George I's sisters were Queen Alexandra of Great Britain, wife of Edward VII, and Russian Empress Maria Feodorovna, wife of Alexander III.

Andrey Georgievich- Prince of Greece and Denmark from the house of Glucksburg, the seventh child and fourth son of George I and Olga Konstantinovna. Great-grandson of Nicholas I, father of Philip of Edinburgh and great-grandfather of Prince William.

Held responsible positions, participated in Balkan Wars. In 1913, after the assassination of his father, his older brother Constantine became King of Greece. Constantine took a neutral policy in the First World War, which caused discontent among the Greeks. This forced Constantine to abdicate and most of his family, including Prince Andrew, were expelled from Greece. After their return a few years later, Prince Andrew took part in the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922, but the war ended poorly for Greece and Prince Andrew was blamed for Greece's territorial losses. He was expelled from Greece for the second time in 1922 and spent most of his life in France. Andrey was married to a princess Alice of Battenberg, great-granddaughter of Queen Victoria of England. Alice's mother, Princess Victoria of Hesse, was the sister of the Russian Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, wife of Nicholas II, and Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna, wife of Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich, son of Alexander II.

Prince Philip was the only son of Prince Andrew and Alice. In Russia they would call him Philip Andreevich. By origin, he was the great-great-great-grandson of the Prussian king Frederick William III, the great-great-grandson of Nicholas I, the great-great-grandson of Queen Victoria of England, the great-grandson of the Danish king Christine IX, the grandson of the Greek king George I. Philip studied in Scotland. Then he entered the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth. From that time on his life was connected with navy. During the Second World War, Lieutenant Prince of Greece was a naval pilot. Took part in the air battle for Britain, accompanied the famous polar sea convoys with Anglo-American assistance Soviet Union. In 1947 he married Princess Elizabeth, his second cousin and Victoria's great-great-granddaughter. Before marriage, he adopted the surname Mountbatten (an anglicized version of his mother’s surname, Battenberg, after the First World War) and converted from Orthodoxy to Anglicanism. In addition, he renounced the titles "Prince of Greece" and "Prince of Denmark" and took British citizenship. On the eve of the marriage, King George VI awarded his future son-in-law the title of Duke of Edinburgh.

What follows is recent history. History of Great Britain. But, nevertheless, all future English kings and queens will have, albeit a small, piece of Russian blood, and genetics is a bizarre science. The Russian gene will pop up in some generation, and the whole world will be surprised by a British monarch with a mysterious Russian soul. At least Prince William marries for love, like all Russians.

Russian empress

Romanova

Years of life: December 18 (29), 1709, p. Kolomenskoye, near Moscow - December 25, 1761 (January 5, 1762), St. Petersburg)

Reign: 1741-1762

From the Romanov dynasty.

Brief biography of Elizaveta Petrovna

Unusually beautiful since childhood, she spent her adolescence and youth in balls and entertainment. She grew up in Moscow, and in the summer she went to Pokrovskoye, Preobrazhenskoye, Izmailovskoye or Alexandrovskaya Sloboda. She rarely saw her father as a child; the future empress was raised by his sister, Tsarevna Natalya Alekseevna, or the family of A.D. Menshikov. She was taught dancing, music, foreign languages, dressing skills, and ethics.

After her parents' marriage, she began to bear the title of princess. The will of Catherine I of 1727 provided for the rights of the crown princess and her descendants to the throne after Anna Petrovna. In the last year of Catherine I's reign, the court often talked about the possibility of a marriage between Elizaveta Petrovna and her nephew Peter II, who was selflessly in love with her. After the sudden death of the young emperor from smallpox in January 1730, despite the will of Catherine I, being still actually illegitimate, she was not considered in high society as one of the contenders for the throne, which was occupied by her cousin. During her reign (1730-1740), the crown princess was in disgrace, but those dissatisfied with Anna Ioannovna and Biron had high hopes for her.

Taking advantage of the decline in authority and influence of power during the regency of Anna Leopoldovna, on the night of November 25, 1741, 32-year-old Tsarevna Elizaveta Petrovna, accompanied by Count M.I. Vorontsov, physician Lestocq and music teacher Schwartz with the words “Guys! You know whose daughter I am, follow me! Just as you served my father, so will you serve me with your loyalty!” raised behind her the grenadier company of the Preobrazhensky Regiment. Thus, a coup d'etat was carried out during which his mother, the ruler-regent Anna Leopoldovna, was overthrown.

The course of state affairs during the entire reign was influenced by her favorites - the brothers Razumovsky, Shuvalov, Vorontsov, A.P. Bestuzhev-Ryumin.

The first document signed by the future empress was a manifesto, which proved that after the death of the previous emperor, she was the only legitimate heir to the throne. She also wished to arrange coronation celebrations in the Assumption Cathedral of the Kremlin and on April 25, 1742 she placed the crown on herself.

Domestic policy of Elizaveta Petrovna

The basic principles of internal and foreign policy the new empress proclaimed a return to Peter's reforms. She abolished the state institutions that arose after the death of her father (the Cabinet of Ministers, etc.), and restored the role of the Senate, collegiums, and the Chief Magistrate.

In 1741, the Empress adopted a Decree that recognized  the existence of the “Lamai faith”, Buddhism was officially adopted as the state religion in the Russian Empire.

the existence of the “Lamai faith”, Buddhism was officially adopted as the state religion in the Russian Empire.

In 1744-1747 The 2nd census of the taxable population was carried out.

In 1754, intrastate customs were eliminated, which led to a significant revival of trade relations between the regions.

The first Russian banks were founded - Dvoryansky (Borrowed), Merchant and Medny (State).

A tax reform was carried out, which improved the financial situation of the country.

In social policy, the line of expanding the rights of the nobility continued. In 1746, the nobles were granted the right to own land and peasants. In 1760, the landowners received the right to exile peasants to Siberia and count them instead of recruits. And peasants were prohibited from conducting monetary transactions without the permission of the landowners.

The death penalty was abolished (1756), and the widespread practice of sophisticated torture was stopped.

Under Elizaveta Petrovna, military educational institutions were reorganized. In 1744, a decree was issued to expand the network primary schools. The first gymnasiums were opened: in Moscow (1755) and Kazan (1758). In 1755, on the initiative of her favorite I.I. Shuvalov founded Moscow University, and in 1760 the Academy of Arts. Outstanding famous cultural monuments have been created (Tsarskoye Selo Catherine Palace, etc.). Support was provided to M.V. Lomonosov and other representatives of Russian culture and science. In 1755, the newspaper “Moskovskie Vedomosti” began to be published, and in 1760 the first Moscow magazine “Useful Amusement” began to be published.

In general, the empress’s internal policy was characterized by stability and a focus on growing the authority and power of state power. Thus, Elizaveta Petrovna’s course was the first step towards a policy of enlightened absolutism.

Foreign policy of Elizaveta Petrovna

Foreign policy in the state was also active. During Russian-Swedish war 1741-1743 Russia received a significant part of Finland. Trying to resist Prussia, the ruler abandoned relations with France and entered into an anti-Prussian alliance with Austria. Russia successfully participated in the Seven Years' War of 1756–1763. After the capture of Koenigsberg, the Empress issued a decree on the annexation of East Prussia to Russia. The culmination of Russia's military glory was the capture of Berlin in 1760.

The basis of foreign policy was the recognition of 3 alliances: with the “maritime powers” (England and Holland) for the sake of trade benefits, with Saxony - in the name of advancement to the northwest and western lands, which ended up being part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and with Austria - to confront the Ottoman Empire and the strengthening of Prussia.

In the last period of her reign, the Empress was less involved in issues of public administration, entrusting it to P.I. and I.I. Shuvalov, M.I. and R.I. Vorontsov and others.

In 1744 she entered into a secret morganatic marriage with A.G. Razumovsky, a Ukrainian Cossack, who under her made a dizzying career from a court singer to the manager of the royal estates and the actual husband of the empress. According to contemporaries, she gave birth to several children, but information about them is unknown. This was the reason for the appearance of impostors who called themselves her children from this marriage. Among them, the most famous figure was Princess Tarakanova.

After the decrees on peasants and landowners were issued, at the turn of the 50-60s. In the 18th century, there were more than 60 uprisings of monastic peasants (Bashkiria, the Urals), which were suppressed by her decree with exemplary cruelty.

The reign of Elizaveta Petrovna

The period of her reign was a period of luxury and excess. Masquerade balls were constantly held at court. Elizaveta Petrovna herself was a trendsetter. The Empress's wardrobe includes up to 12-15 thousand dresses, which today form the basis of the textile collection of the State Historical Museum in Moscow.

Since 1757, she began to be haunted by hysterical fits. She often lost consciousness, and at the same time, non-healing wounds on her legs and bleeding opened. During the winter of 1760-1761, the Empress was on a large outing only once. Her beauty was quickly destroyed, she did not communicate with anyone, feeling depressed. Soon the hemoptysis intensified. She confessed and received communion. Elizaveta Petrovna died on December 25, 1761 (January 5, 1762 according to the new style).

The ruler managed to appoint her nephew Karl-Peter-Ulrich of Holstein-Gottorp (son of Anna's sister) as the official heir to the throne, who converted to Orthodoxy under his name and made peace with Prussia.

The body of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna was buried on February 5, 1762 in the Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg.

Many artists painted her portraits, marveling at the beauty of the empress.

Her image is reflected in cinema: in the films “Young Catherine”, 1991; “Vivat, midshipmen!”; "Secrets palace coups", 2000-2003; “With a pen and a sword”, 2008.

She had a practical mind and skillfully led her court, maneuvering between various political factions. Generally years of reign of Elizaveta Petrovna became a time of political stability in Russia, strengthening of state power and its institutions.

Download the abstract.