Turkish war 1828 1829 results. Russian-Turkish war (1828-1829). Balkan theater of operations

Russian-Turkish war 1828 - 1829

| Parameter name | Meaning |

| Article subject: | Russian-Turkish war 1828 - 1829 |

| Rubric (thematic category) | Policy |

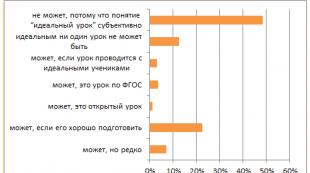

In April 1828 ᴦ. Russia declared war on Turkey. The main fighting took place in the Balkans and Transcaucasia. Nicholas I himself went to the Balkan theater of operations. The Turkish Sultan had 80,000 army. In April 1828 ᴦ. 95 thousand the Russian army under the command of the aged Field Marshal P.Kh. Wittgenstein made a lightning march from Bessarabia and in a matter of days occupied Moldavia and Wallachia. The entire Turkish army also crossed the Danube and occupied the entire northern Dobruja. At the same time, the Caucasian army of I.F. Paskevich occupied Turkish fortresses on the eastern coast of the Black Sea - Anapa, Poti, Akhaltsikhe, Akhalkalakhi, Bayazet, Kars. But the campaign of 1828 ᴦ. turned out to be unsuccessful. At the beginning of the next 1829 ᴦ. I.I. was appointed commander-in-chief of the Russian army. Dibich. After that, the emperor retired from the active army, since his presence fettered the actions of the military command. I.I. Diebitsch reinforced the army, June 19, 1829 ᴦ. the well-fortified fortress of Silistria was taken. Further, the Russian army, having overcome incredible difficulties, unexpectedly for the Turks, crossed the main Balkan ridge. During July, 30,000 the Russian army defeated 50 thousand Turks and in August marched to Adrianople, the second most important Turkish city after Istanbul. At the same time, I.F. Paskevich defeated the Turkish army in the Caucasus. On August 7, Russian troops were already standing under the walls of Adrianople, the next day the city surrendered to the mercy of the victors. The Turkish Sultan prayed for peace. Never since the times of Ancient Rus' have Russian troops been so close to Istanbul (Constantinople). But the collapse of the Ottoman Empire posed a great threat to world peace. September 2, 1829 ᴦ. The Adrianople Peace Treaty was signed, according to which Russia gave Turkey all the conquered territories, but received Turkish cities - fortresses on the eastern coast of the Black Sea: Kars, Anapa, Poti, Akhaltsikhe, Akhalkalaki. The port recognized the independence of Greece, confirmed the autonomy of Moldavia, Wallachia, Serbia (the rulers there were to be appointed for life).

Russia's success in the fight against Turkey caused great concern among the powers of Western Europe. The impressive military successes of Russia once again showed that the decrepit Ottoman Empire was on the verge of collapse. England and France already claimed Balkan possessions. Οʜᴎ feared that Russia alone would achieve the complete defeat of the Ottoman Empire, take possession of Istanbul and the Bosphorus and Dardanelles, which at that time occupied the most important military-strategic importance in the world. An alliance of the strongest states against Russia was formed. England and France, in order to weaken Porto and Russia, began to vigorously push them to war.

Russian-Turkish war 1828 - 1829 - concept and types. Classification and features of the category "Russian-Turkish war of 1828 - 1829." 2017, 2018.

After the Congress of Vienna (1814-1815), Russia returned to resolving the "Balkan issue", which did not lose its relevance as a result of the Russian-Turkish war of 1806-1813. Seeing the opponent's weakness, Alexander I even put forward the idea of granting independence to Orthodox Serbia. The Turks, counting on the help of England and Austria, showed intransigence and demanded that Sukhum and several other fortresses in the Caucasus be returned to them.

In 1821, a national liberation uprising broke out in Greece, which was brutally suppressed by the Turkish authorities. Russia resolutely came out for an end to violence against Christians and turned to European countries with a proposal to put joint pressure on the Ottoman Empire. However, the European states, fearing a sharp increase in Russian influence in the Balkans, did not show much interest in the fate of the Greeks.

In 1824, Alexander I took the initiative to grant autonomy to Greece, but was resolutely refused. Moreover, Türkiye has landed a large punitive corps in Greece.

Nicholas I continued the policy of his elder brother. In 1826, Russia advocated the creation of an anti-Turkish coalition of European states. On his side, he planned to attract Great Britain and France. The king sent an ultimatum to the Turkish sultan Mahmud II, in which he demanded the restoration of the full autonomy of Serbia and the Danubian principalities. Nicholas II informed the British envoy - Duke A.U. Wellington (the winner at Waterloo) and declared that now, if England does not support him, he will be against Turkey alone. Of course, Great Britain could not allow such important issues to be decided without its participation. France soon joined the coalition. It is worth noting that the creation of the Russian-Anglo-French alliance, designed to support the "rebellious" Greeks in their struggle against the "legitimate power" of the Turkish Sultan, was a serious blow to the legitimist principles of the sacred alliance.

On September 25, 1826, Turkey accepted the terms of the ultimatum of Nicholas I and signed a convention in Akkerman, in which it confirmed the autonomy of the Danubian principalities and Serbia, and also recognized Russia's right to patronize the Slavic and Orthodox peoples of the Balkan Peninsula. However, on the Greek question, Mahmud II did not want to back down. In April 1827, the Greek National Assembly elected in absentia the head of state of the Russian diplomat I. Kapodistrias, who did not hesitate to turn to Nicholas I for help.

On October 20, 1827, the Anglo-French-Russian squadron under the command of the British Admiral E. Codrington defeated the Turkish fleet in the Navarin harbor. The Russian cruiser Azov fought especially bravely, captained by M.P. Lazarev, and his assistants P.S. Nakhimov, V.I. Istomin and V.A. Kornilov - the future heroes of the Crimean War.

After this victory, Britain and France announced that they were refusing further military action against Turkey. Moreover, British diplomats pushed Mahmud II to aggravate the conflict with Russia.

April 14, 1828 Nicholas I declared war on the Ottoman Empire. There were two fronts: the Balkan and the Caucasian. On the Balkan Peninsula, the 100,000-strong Russian army under the command of P.Kh. Wittgenstein occupied the Danubian principalities (Moldavia, Wallachia and Dobruja). After that, the Russians began to prepare an attack on Varna and Shumla. The number of Turkish garrisons of these fortresses significantly exceeded the number of Russian troops besieging them. The siege of Shumla was unsuccessful. Varna was taken at the end of September 1828, after a long siege. The military operation dragged on. In the Caucasus, the corps of General I.F. Paskevich blocked Anapa, and then moved to the Kars fortress. In the summer, he managed to win Ardagan, Bayazet and Poti from the Turks. By the beginning of the 1829 campaign, Russia's relations with England and Austria had deteriorated significantly. The danger of their intervention in the war on the side of Turkey has increased. It was necessary to hasten the end of the war. In 1829, the command of the Balkan army was entrusted to General I.I. Dibich. He stepped up the offensive. In the battle near vil. Kulevcha (May 1829) Dibich defeated the 40,000th Turkish army, and in June captured the fortress of Silistria, after which he crossed the Balkan Mountains and captured Adrianople. At the same time, Paskevich occupied Erzurum.

August 20, 1829 to General I.I. Turkish representatives arrived to Dibich with a proposal for peace talks. On September 2, the Treaty of Adrianople was signed. Under its terms, Russia acquired part of the Danube Delta and eastern Armenia, and the Black Sea coast from the mouth of the Kuban to the city of Poti also passed to it. The freedom of commercial navigation through the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles was established in peacetime. Greece received full autonomy, and in 1830 became an independent state. The autonomy of Serbia, Wallachia and Moldavia was confirmed. Türkiye pledged to pay an indemnity (30 million in gold). England's attempts to achieve a softening of the terms of the peace of Adrianople were decisively rejected.

As a result of the war, Russia's prestige in the Balkans increased. In 1833, Nicholas I assisted the Ottoman Empire in the fight against the rebellious ruler of Egypt, Mohammed Ali. In June of this year, the commander of the Russian troops, A.F. Orlov, on behalf of the Russian Empire, signed a friendly agreement with the Sultan (for a period of 8 years), which went down in history under the name of the Unkar-Iskelesi Treaty. Russia guaranteed the security of Turkey, and she, in turn, undertook to close the Black Sea straits to all foreign (except Russian) warships. The violent indignation of the European powers forced Russia in 1840 to sign the London Convention and withdraw its fleet from the Bosporus.

Russo-Turkish War 1828-1829

The history of Russian-Turkish wars goes back to the 17th century. At first, these were wars between the Muscovite state and the Ottoman Empire (Turkey). Until the 18th century, the Crimean Khanate always stood on the side of the Ottoman Empire. On the part of Russia, the main reason for the wars was the desire to gain access to the Black Sea, and later to establish itself in the Caucasus.

Causes of the war

The military conflict between the Russian and Ottoman empires in 1828 arose as a result of the fact that after the Battle of Navarino in October 1827, the Port (the government of the Ottoman Empire) closed the Bosphorus, violating the Akkerman Convention. Ackermann Convention- an agreement between Russia and Turkey, concluded on October 7, 1826 in Akkerman (now it is the city of Belgorod-Dnestrovsky). Turkey recognized the border along the Danube and the transition to Russia of Sukhum, Redut-Kale and Anakria (Georgia). She undertook to pay within a year and a half all the claims of Russian citizens, to give Russian citizens the right to unhindered trade throughout Turkey, and to Russian merchant ships the right to navigate freely in Turkish waters and along the Danube. The autonomy of the Danubian principalities and Serbia was guaranteed, the rulers of Moldavia and Wallachia were to be appointed from local boyars and could not be removed without the consent of Russia.

But if we consider this conflict in a broader context, then it must be said that this war was caused by the fact that the Greek people began the struggle for independence from the Ottoman Empire (back in 1821), and France and England began to help the Greeks. Russia at that time pursued a policy of non-intervention, although it was in alliance with France and England. After the death of Alexander I and the accession to the throne of Nicholas I, Russia changed its attitude towards the Greek problem, but at the same time, disagreements began between France, England and Russia on the issue of dividing the Ottoman Empire (sharing the skin of an unkilled bear). The Port immediately announced that it was free from agreements with Russia. Russian ships were banned from entering the Bosphorus, and Turkey intended to transfer the war with Russia to Persia.

Porta moved its capital to Adrianople and strengthened the Danube fortresses. Nicholas I at that time declared war on Porte, and she declared war on Russia.

The course of the war in 1828

J. Dow "Portrait of I. Paskevich"

On May 7, 1828, the Russian army under the command of P.Kh. Wittgenstein (95 thousand) and the Separate Caucasian Corps under the command of General I.F. Paskevich (25 thousand) crossed the Prut, occupied the Danube principalities and crossed the Danube on June 9. Isakcha, Machin and Brailov capitulated one by one. At the same time, a sea expedition to Anapa took place.

Then the advance of the Russian troops slowed down. Only on October 11 they were able to take Varna, but the siege of Shumla and Silistria ended in failure. At the same time, the attempts of the Turks to invade Wallachia were neutralized by the victory of the Russians at Baileshti (modern Beileshti). In the Caucasus in the summer of 1828, a decisive offensive was launched by the corps of I.F. Paskevich: in June he captured Kars, in July Akhalkalaki, in August Akhaltsikhe and Bayazet; the entire Bayazet pashalyk (province of the Ottoman Empire) was occupied. In November, two Russian squadrons blocked the Dardanelles.

Assault on Kars Fortress

Ya. Sukhodolsky "Storm of the Kars Fortress"

The day of June 23, 1828 occupies a special place in the history of the Russian-Turkish war. An impregnable fortress fell before a small army, having seen formidable conquerors many times at its walls, but never within its walls.

The siege of the fortress went on for three days. And Kars bowed before the victors with the inaccessible peaks of his towers. Here's how it happened.

By the morning of June 23, the Russian troops stood under the fortress, they were under the general command of Major General Korolkov and Lieutenant General Prince Vadbolsky, Major General Muravyov, the Erivan Carabinieri Regiment and the reserve Georgian Grenadier Regiment and the consolidated cavalry brigade.

With the first rays of the sun, all Russian batteries began a cannonade on the Turkish camp. In response to this, the strongest fire began from all tiers of the citadel. Sixteen Russian guns could hardly respond to this cannonade. “It is unlikely that during my entire service I was in a stronger fire than on this day,” said Muravyov, a member of Borodin, Leipzig and Paris. “If such firing continued for another two hours, the battery would have been razed to the ground.”

When the batteries of the Turkish camp fell silent, part of the enemy infantry descended from the fortified height and began close combat. There was a hand-to-hand fight.

The Russian soldiers were led by Miklashevsky and Labintsev, their courage knew no bounds. Having defeated the enemy, the soldiers began to pursue those fleeing to the camp up the mountain. It was very dangerous, but the officers could not stop the Russian soldiers. "Stop, brothers! Stop! they shouted. It's just a fake attack!"

“It’s impossible, your honor,” one of the soldiers answered as they ran, “it’s not the first time we have to deal with a non-Christ. Until you crack him in the teeth, he can’t understand this fake attack in any way. ”

The course of the war in 1829

In the spring of 1829, the Turks tried to take revenge and recapture Varna, but on June 11, the new Russian commander in chief I.I. Dibich defeated the twice superior forces of the Grand Vizier Reshid Pasha near the village. Kulevcha. Silistria surrendered on June 30, in early July the Russians crossed the Balkans, captured Burgas and Aidos (modern Aitos), defeated the Turks near Slivno (modern Sliven) and entered the Maritsa valley. On August 20, Adrianople capitulated. In the Caucasus, I.F. Paskevich in March and June 1829 repulsed the attempts of the Turks to return Kars, Bayazet and Guria, captured Erzerum on July 8, captured the entire Erzerum pashalik and went to Trabzon.

J. Dow "Portrait of I. Dibich"

Numerous defeats forced Sultan Mahmud II to enter into negotiations. But the Turks dragged them out in every possible way, hoping for Austrian intervention. Then I.I. Dibich moved to Constantinople. The ambassadors of the Western powers recommended that Sultan Mahmud accept the Russian conditions. On September 14, the Peace of Adrianople was concluded : The Ottoman Empire ceded to Russia the Black Sea coast of the Caucasus from the mouth of the Kuban to Fort St. Nicholas, the Akhaltsikhe pashalyk and the islands in the Danube Delta, granted autonomy to Moldavia, Wallachia and Serbia, recognized the independence of Greece; The Bosphorus and the Dardanelles were opened to the courts of all countries; Russia received the right to free trade throughout the territory of the Ottoman Empire.

The feat of the brig "Mercury"

I. Aivazovsky "Brig" Mercury "attacked by two Turkish ships"

"Mercury"- 18-gun military brig of the Russian fleet. It was launched on May 19, 1820. In May 1829, during the Russian-Turkish war, the brig under the command of lieutenant commander Alexander Ivanovich Kazarsky won a victory in an unequal battle with two Turkish battleships, for which he was awarded the stern St. George flag.

At the end of the Russian-Turkish war of 1828-1829, the Black Sea Fleet continued its tight blockade of the Bosphorus. Detachments of Russian ships were constantly on duty at the entrance to the strait in order to timely detect any attempt by the Turkish fleet to go to sea. In May 1829, a detachment of ships under the command of Captain-Lieutenant P. Ya. Sakhnovsky was assigned to cruising at the entrance to the Bosphorus. The detachment included the 44-gun frigate "Standard", the 20-gun brig "Orpheus" and the 18-gun brig "Mercury" under the command of Lieutenant Commander A. I. Kazarsky. The ships left Sizopol on May 12 and headed for the Bosphorus.

Early in the morning of May 14, a Turkish squadron appeared on the horizon, marching from the shores of Anatolia (the southern coast of the Black Sea) to the Bosphorus. "Mercury" went into a drift, and the frigate "Standart" and the brig "Orpheus" went to approach the enemy to determine the composition of the Turkish squadron. They counted 18 ships, among which were 6 battleships and 2 frigates. The Turks discovered the Russian ships and gave chase. Sakhnovsky ordered each ship to leave the chase on their own. Shtandart and Orpheus set all sails and quickly disappeared over the horizon. "Mercury" also left in full sail, but two Turkish ships began to catch up with him. These were 110-gun and 74-gun ships. The rest of the Turkish ships lay adrift, watching the admirals hunt for the small Russian brig.

About two o'clock in the afternoon the wind died down and the chase stopped. Kazarsky ordered to move on the oars. But half an hour later the wind picked up again, and the chase resumed. Soon the Turks opened fire from linear guns (guns designed to fire straight ahead). Kazarsky invited the officers to a military council. The situation was extremely difficult. In terms of the number of guns, the two Turkish ships outnumbered the Mercury by 10 times, and by the weight of the side salvo - 30 times. Lieutenant of the Corps of Naval Navigators I.P. Prokofiev offered to fight. The council unanimously decided to fight to the last extremity, and then to fall with one of the Turkish ships and blow up both ships. Encouraged by this decision of the officers, Kazarsky appealed to the sailors not to disgrace the honor of the Andreevsky flag. All as one declared that they would be faithful to their duty and oath to the end.

The team quickly prepared for battle. Kazarsky was already an experienced naval officer. For distinction during the capture of Anapa, he was promoted ahead of schedule to lieutenant commander, and then again committed a heroic deed during the siege of Varna, for which he was awarded a golden saber with the inscription "For courage!" and was appointed commander of the brig "Mercury". Like a real naval officer, he was well aware of the strengths and weaknesses of his ship. It was strong and had good seaworthiness, but because of the shallow draft it was slow. In this situation, only the maneuver and accuracy of the gunners could save him.

For half an hour, using oars and sails, "Mercury" avoided enemy airborne salvos. But then the Turks nevertheless managed to get around it from two sides, and each of the Turkish ships fired two broadside volleys at the brig. A hail of cannonballs, knipels (two cannonballs connected by a chain or rod are used to disable the ship's rigging) and brandskugels (incendiary projectiles) rained down on him. After that, the Turks offered to surrender and lie adrift. The brig responded with a volley of carronades (a short cast-iron cannon) and friendly fire from guns. Kazarsky was wounded in the head, but continued to lead the battle. He perfectly understood that his main task was to deprive the Turkish ships of the course, and ordered the gunners to aim at the rigging and spars of the Turkish ships.

I. Aivazovsky "The brig "Mercury" after the victory over the Turkish ships goes towards the Russian squadron"

This tactic of the Russian brig was fully justified: several cores from the Mercury damaged the rigging and mainmast of one ship, and it went out of order. And the other continued to attack with even greater perseverance. For an hour he hit the brig with hard longitudinal volleys. Then Kazarsky decided on a desperate maneuver. The brig abruptly changed course and went to rendezvous with the Turkish ship. Panic began on the Turkish ship: the Turks decided that the Russians would blow up both ships. Having approached the shortest distance, Kazarsky allowed his gunners to hit the gear of the Turkish ship with maximum accuracy. The risk was very great, because the Turks could now shoot point-blank at the Mercury from their huge guns. But our gunners broke several yards, and the sails began to fall on the deck, the Turkish ship could not maneuver. "Mercury" fired another volley at him and began to leave. And "Standard" and "Orpheus" on the same day with half-mast flags arrived in Sizopol. They reported the appearance of the Turkish fleet and the death of the Mercury. The commander of the fleet, Vice Admiral A. S. Greig, ordered to immediately go to sea in order to cut off the Turkish fleet from the Bosphorus. The next day, the Russian squadron on the way to the Bosphorus met the brig "Mercury". The appearance of the ship spoke for itself, but the wounded brig proudly went to join his squadron. Kazarsky boarded the flagship and reported on the heroic actions of the officers and crew. Vice Admiral A. S. Greig, in a detailed report to Emperor Nicholas I, emphasized that the crew of the brig had committed "a feat that is not comparable in the annals of the sea powers". After that, "Mercury" continued its journey to Sevastopol, where a solemn meeting awaited him.

For this battle, Kazarsky was promoted to captain of the 2nd rank, awarded the Order of St. George 4th degree and received the title of adjutant wing. All officers of the brig were promoted and awarded orders, and the sailors were awarded the insignia of a military order. All officers and sailors were given a lifetime pension in the amount of a double salary. The officers were allowed to include in their coats of arms the image of a pistol that was prepared to blow up the ship. In honor of the feat of the Mercury crew, a commemorative medal was cast. The brig was the second of the Russian ships to receive a commemorative St. George flag and a pennant. The news of the unprecedented victory of our small patrol vessel over the two strongest ships of the Turkish fleet quickly spread throughout Russia. Kazarsky became a national hero.

A.I. Kazarskiy

Further history of "Mercury"

"Mercury" served in the Black Sea Fleet until November 9, 1857. After that, three ships alternately bore the name "Memory of Mercury", receiving and transmitting its St. George's flag. Kazarsky died suddenly in 1833 in Nikolaev, when he was less than 36 years old. There is reason to believe that he was poisoned by stealing port officials in order to cover up the traces of their crimes. The next year, a monument to one of the first heroes of the city was erected on Michmansky Boulevard of Sevastopol. The initiative to install it was made by the commander of the Black Sea squadron MP Lazarev. The famous architect A.P. Bryullov became the author of the project. On the granite pedestal of the monument is carved a very brief, but significant inscription: “Kazarsky. An example for posterity.

Monument to A.I. Kazarsky

Outcome of the war

September 14, 1829 between the two parties was signed Peace of Adrianople, as a result of which most of the eastern coast of the Black Sea (including the cities of Anapa, Sudzhuk-Kale, Sukhum) and the Danube Delta passed to Russia.

The Ottoman Empire recognized the transfer to Russia of Georgia, Imeretia, Mingrelia, Guria, as well as the Erivan and Nakhichevan khanates (transferred by Iran through the Turkmanchai world).

Türkiye reaffirmed its obligations under the Akkerman Convention of 1826 to respect the autonomy of Serbia.

Moldavia and Wallachia were granted autonomy, and Russian troops remained in the Danubian principalities for the duration of the reforms.

Türkiye also agreed to the terms of the London Treaty of 1827 granting autonomy to Greece.

Turkey pledged to pay Russia an indemnity in the amount of 1.5 million Dutch chervonets within 18 months.

Medal for participation in the Russian-Turkish war of 1828-1829

war between Russia and Turkey over the territories of Transcaucasia and the Balkan Peninsula.

This war was part of the Eastern Question. Türkiye was prepared for war worse than Russia. In the Caucasus, the Russian army took the Turkish fortresses of Kars and Bayazet. In the Balkans in 1829, the Russian army inflicted a number of defeats on Turkish troops and took the city of Adrianople, located near the capital of Turkey. In September 1829, the Treaty of Adrianople was signed. Significant territories of the Black Sea coast of the Caucasus and part of the Armenian regions belonging to Turkey passed to Russia. Wide autonomy for Greece was guaranteed. In 1830 an independent Greek state was created.

(See the historical map "The territory of the Caucasus, ceded to Russia by the 1830s").

Great Definition

Incomplete definition ↓

Russo-Turkish War 1828-1829

After the defeat in 1827 of the Egyptian-Turkish fleet in Navarin Bay by a united Anglo-French-Russian squadron, relations between the European powers and Turkey became more complicated. This created a tactical advantage for Russia, which could now act more decisively against Turkey. The Turkish government, by its policy, only facilitated the armed uprising of Russia. It refused to implement the Akkerman Convention concluded with Russia in 1826, in particular the article on the rights and privileges of Moldavia, Wallachia and Serbia, and subjected Russian maritime trade to constraint.

The successful completion of the war with Iran and the signing of the Turkmenchay peace allowed Nicholas I to start a war against Turkey. In the spring of 1828, Russian troops crossed the border.

The international situation favored Russia. Of all the great powers, only Austria openly provided material assistance to the Turks. England, by virtue of the convention of 1827 and her participation in the Battle of Navarino, was forced to remain neutral. France, for the same reasons and in view of the established close ties between the Bourbon government and the tsarist government, also did not oppose Russia. Prussia also took a benevolent position towards Russia.

Nevertheless, numerous mistakes of the Russian command delayed the war until the autumn of 1829. The outcome of the war in Asia was decided after the capture of an important strategic point - Erzurum (1829) by Paskevich's army. In the European theater of war, Dibich's army broke through the Balkans, entered the valley of the Maritsa River and entered the city of Adrianople (Edirne), threatening to occupy Constantinople (Istanbul).

After these Russian military successes, the Turkish government, under pressure from England, who feared the occupation of the Turkish capital and the Black Sea straits by Russian troops, entered into peace negotiations, and on September 14, 1829, a Russian-Turkish peace treaty was signed in Adrianople. Under its terms, the border between Russia and Turkey in the European part was established along the Prut River to its confluence with the Danube. The entire Black Sea coast of the Caucasus from the mouth of the Kuban to the post of St. Nicholas (near Poti) finally passed to Russia. Turkey recognized the accession to Russia of the regions of Transcaucasia, which became part of Russia in 1801-1813, and also in accordance with the Turkmenchay peace treaty with Iran.

Moldavia and Wallachia retained internal autonomy with the right to have a “zemstvo army”. In relation to Serbia, which started a new uprising, the Turkish government undertook to fulfill the terms of the Bucharest Treaty on granting the Serbs the right to convey through their deputies to the Sultan demands for the urgent needs of the Serbian people. In 1830, a sultan's decree was issued, according to which Serbia was recognized as independent in internal administration, but a vassal principality in relation to Turkey.

An important consequence of the Russian-Turkish war was the granting of independence to Greece. In the Treaty of Adrianople, Türkiye accepted all the conditions that determined the internal structure and borders of Greece. In 1830 Greece was declared completely independent. However, Greece did not include part of Epirus, Thessaly, the island of Crete, the Ionian Islands and some other Greek lands. After lengthy negotiations between England, France and Russia regarding the structure of Greece, a monarchy was formed there, headed by the German prince Otto. Soon Greece fell under the financial and then political control of England.

Strengthening of Russia's position in the Balkans and Asia as a result of the war of 1828-1829. further exacerbated the Eastern question.

By this time, the position of Turkey had become much more complicated in connection with the open speech of the Egyptian Pasha Muhammad Ali against the Sultan.

Great Definition

Incomplete definition ↓

Turkish Sultan Mahmoud II, having learned about the extermination of his naval forces at Navarino, he became more embittered than before. The envoys of the allied powers had lost all hope of persuading him to accept London treatise and left Constantinople. Following that, in all the mosques of the Ottoman Empire, a hatt-i-sherif (decree) was promulgated on the universal militia for faith and fatherland. The Sultan proclaimed that Russia was the eternal, indomitable enemy of Islam, that she was plotting the destruction of Turkey, that the uprising of the Greeks was her work, that she was the true culprit of the London Treaty, which was harmful to the Ottoman Empire, and that the Porte, in recent negotiations with her, tried only to gain time and gather strength, deciding in advance not to fulfill Ackermann Convention.

The court of Nicholas I responded to such a hostile challenge with deep silence and for four whole months hesitated to announce a break, still not losing hope that the sultan would reflect on the inevitable consequences of a new Russian-Turkish war and agree to peace; hope was futile. He called Russia to war not only with words, but also with deeds: he insulted our flag, delayed ships and did not open the Bosphorus, which stopped any movement of our Black Sea trade. Not only that: at the very time when the peace agreements between Russia and Persia were drawing to a close, Turkey, by hastily arming its troops and secretly promising strong support, shook the peace-loving disposition of the court of Tehran.

Forced to draw his sword in defense of the dignity and honor of Russia, the rights of his people, acquired by victories and treaties, the sovereign emperor Nicholas I announced publicly that, contrary to the disclosures of the sultan, he did not think at all about the destruction of the Turkish Empire or the expansion of his power and would immediately stop hostilities , begun by the Battle of Navarino, as soon as the Port satisfies Russia in its just demands, already recognized by the Ackermann Convention, provides for the future with a reliable guarantee the validity and exact execution of the previous treaties and proceeds to the terms of the London Treaty on Greek Affairs. Such a moderate response of Russia to the Turkish declaration, filled with malice and irreconcilable hatred, disarmed and calmed the most incredulous envious of our political power. European cabinets could not but agree that it was impossible to act more noble and generous than the Russian emperor. God bless his righteous cause.

The Russian-Turkish war began in the spring of 1828. On our part, an extensive plan of military operations was outlined in order to disturb Turkey from all sides and to convince Porto of the impossibility of fighting Russia with combined, unified strikes by land and sea forces in Europe and Asia, on the Black and Mediterranean seas. Field Marshal Count Wittgenstein instructed by the main army to occupy Moldavia and Wallachia, cross the Danube and inflict a decisive blow on the enemy on the fields of Bulgaria or Rumelia; Count Paskevich-Erivansky was ordered to attack the Asian regions of Turkey with the Caucasian corps in order to divert her forces from Europe; Prince Menshikov with a separate detachment to take Anapa; Admiral Greig with the Black Sea Fleet to assist in the conquest of coastal fortresses in Bulgaria, Rumelia and on the eastern coast of the Black Sea; Admiral Heyden with a squadron stationed in the Archipelago, to lock up the Dardanelles to prevent the delivery of food supplies from Egypt to Constantinople.

Campaign of 1828 in the Balkans

The main army, numbering 15,000 people, having started the Russian-Turkish war, crossed the border of the empire, the Prut River, at the end of April 1828 in three columns: the right one, almost without a shot, captured Iasi, Bucharest, Craiova, occupied Moldavia and Wallachia and saved both principalities with a quick movement from the malice of the Turks, who intended to destroy both completely. Moldavians and Vlachs greeted the Russians as deliverers. The middle column, entrusted to the main authorities of Grand Duke Mikhail Pavlovich, turned to Brailov and laid siege to it, in order to secure the rear of the army across the Danube by taking this fortress, which is important in its strategic position on the path of our military operations. Below Brailov, against Isakcha, the troops of the left column, more numerous than others, concentrated to cross the Danube.

Russian-Turkish war 1828-1829. Map

Here the Russian army faced one of the most glorious feats of the Russian-Turkish war of 1828-1829: due to an unusual flood of spring waters, the Danube overflowed its banks and flooded the surroundings over a vast area. The left, low side of it turned into an impenetrable swamp; in order to reach the bank of the river and build a bridge over it, it was necessary first to make an embankment, like those gigantic works with which the Romans still surprise us. The troops, inspired by the presence of the Sovereign Emperor, who shared the labors of the campaign with them, quickly set to work and built a dam over an area of 5 versts. The Turks also did not remain inactive: as we built the embankment, they erected batteries that threatened to destroy all our efforts to build a bridge with a crossfire.

A favorable event made it easier for us to clear the right bank of the enemy. The Zaporizhzhya Cossacks, who had long lived at the mouth of the Danube under the auspices of the Porte, but who did not betray the faith of the forefathers, having learned that the sovereign emperor himself was in the Russian camp, expressed a desire to strike the Orthodox tsar with his brow and, carried away by his complacency, agreed to return to the bowels of their ancient fatherland. All of their kosh moved to the left bank, with all the foremen and the ataman. Hundreds of light ships were now at our disposal. Two regiments of chasseurs boarded the Zaporizhian canoes, crossed the Danube, took possession of the Turkish batteries and hoisted the Russian banner on the right bank. Following this, in orderly order, all the troops assigned for offensive operations in Bulgaria crossed over. Sovereign Emperor Nicholas, himself leading the crossing, crossed the Danube waves in a Zaporizhzhya boat, driven by a ataman.

Across the Danube, the Ottomans did not dare to meet us in the open field and locked themselves in the fortresses that served as a stronghold in the Port in the previous Russo-Turkish wars. The main points defended by them, besides Brailov, were Silistria, Ruschuk, Varna and Shumla. Each of these fortresses had a numerous garrison, reliable fortifications and experienced military leaders. In Shumla, impregnable in its position, 40,000 of the best Turkish troops were concentrated under the command of the courageous seraskir Hussein Pasha. Beyond the Balkans stood a vizier with a reserve army to defend Constantinople.

In our main quarters, it was decided to start a war by moving directly to Shumla, in order to test whether it would be possible to lure the seraskir into battle and, by defeating his troops, open the way beyond the Balkans. The small transdanubian fortresses of Isakcha, Tulccha, Machin, Girsova, Kistenji, lying on our way, could not delay us: they were taken one by one by separate detachments. But the stubborn defense of Brailov, on the left bank of the Danube, in the rear of the Russian army, forced her to stop for a while near the Trayanov Wall. Having waited for the fall of Brailov, the troops again moved forward; they walked in the midst of unbearable heat, a country so barren and meager that they had to carry the smallest things, even coal. Unhealthy water gave rise to disease; horses and oxen died by the thousands from lack of food. The valiant Russian soldiers overcame all obstacles, drove the enemy troops out of Pazardzhik and approached Shumla.

Hope for a fight was not fulfilled: Hussein remained motionless. It was difficult to take Shumla by attack or by a regular siege, at least, cruel bloodshed had to be feared, and in case of failure, it would have been necessary to return across the Danube. It also turned out to be impossible to enclose it from all sides, in order to prevent the supply of food supplies, due to the small number of troops. To pass Shumla and go straight beyond the Balkans would mean leaving a whole army in the rear, which could attack us in the Balkan gorges from behind, while the vizier would strike from the front.

Capture of Varna

The Russian emperor, avoiding any wrong undertaking, ordered Field Marshal Wittgenstein to remain near Shumla to observe Hussein; meanwhile, the detachment of Prince Menshikov, who had already defeated Anapa, with the assistance of the Black Sea Fleet, capture Varna, and the corps of Prince Shcherbatov Silistria. The capture of the first fortress provided food for the Russian troops by transporting provisions from Odessa by sea; the fall of the second was recognized as necessary for the safety of our army's winter quarters across the Danube.

The siege of Varna lasted two months and a half. The small detachment of Prince Menshikov turned out to be too insufficient to conquer a first-class fortress, defended by a favorable location, strongholds that always reflected all our efforts during the previous Russian-Turkish wars, and the courage of a 20,000 garrison, under the command of a brave captain-pasha, a favorite of the Sultan. In vain the Black Sea Fleet, animated by the presence of the sovereign emperor, smashed Varna from the sea: she did not give up. The arrival of the Russian guards to help the siege corps gave a different turn to military operations. No matter how actively the garrison resisted, our work quickly moved to the very walls of the fortress, and all the efforts of the Turkish commander Omar-Vrione to save Varna by attacking the besiegers from the Balkan Mountains were in vain: repulsed by Prince Eugene of Württemberg and the brave Bistrom, he had to go into the mountains. September 29, 1828 Varna fell at the feet of the Russian emperor. Its conquest, having provided food for the Russian troops in Bulgaria, at the same time deprived Shumla of its former importance in a strategic sense: the route to Rumelia through the Balkans was open from the sea, and only the early winter forced us to postpone decisive action until the next campaign of this Russian-Turkish war. Count Wittgenstein returned across the Danube, leaving strong detachments in Varna, Pazardzhik and Pravoda.

Campaign of 1828 in Transcaucasia

Meanwhile, in the Russo-Turkish war of 1828-1829, miraculous, incredible deeds took place beyond the Caucasus: impregnable fortresses fell before a handful of the brave and numerous enemies disappeared. Acting defensively in Europe, the Turkish sultan thought of inflicting a strong blow on us in Asia, and at the very beginning of the war he ordered the Erzurum Seraskier with 40,000 army to invade our Transcaucasian regions at different points, with full hope of success. In fact, the state of our affairs in that region was very difficult. The main Russian army had already crossed the Danube, and the Transcaucasian corps barely had time to return from the Persian campaign, exhausted by battles and illnesses; there were no more than 12,000 people in its ranks. Food supplies and military ammunition were depleted; transports and artillery parks could barely serve. The Muslim provinces subject to us, shaken by the appeals of the Sultan, were only waiting for the appearance of fellow-believing Turks in order to rise up against us without exception; the owner of Guria, plotting treason, communicated with the enemy; in the auls of the highlanders, general unrest prevailed. It took a lot of intelligence, art and spiritual strength to avert the dangers that threatened the Transcaucasian region at the beginning of the Russian-Turkish war of 1828-1829. But Paskevich did more: the thunder of his victories stunned the enemies and made the Sultan tremble in Constantinople itself.

Russian-Turkish war 1828-1829. Siege of Kars in 1828. Painting by J. Sukhodolsky, 1839

Knowing that only a quick and bold blow could stop the enemy’s formidable desire for the Transcaucasian region, Paskevich decided on a brave feat: with 12,000 corps, he moved (1828) to the borders of Asiatic Turkey and, beyond the expectations of the enemies, appeared under the walls of Kars, a fortress famous in Turkish annals: they remembered that she repelled Shah Nadir, who without success besieged her for 4 whole months with 90,000 troops. In vain were our efforts to seize it in 1807, during the Russian-Turkish war of 1806-1812. Count Paskevich did not stand near Kars even for four days. He took it by storm. Turkish troops sent by the Seraskir to invade Georgia from Kars retreated to Erzerum.

Capture of Akhaltsikhe by Paskevich (1828)

Meanwhile, the most important danger threatened the Russian borders from the other side: up to 30,000 Turks rushed to the borders of Guria, along the Akhaltsikhe road, under the command of two noble pashas. hurried to warn them near Akhaltsikhe. An unexpected obstacle stopped him: a plague had opened in the corps; a rare regiment did not become infected. Saving his brave companions from death, the commander-in-chief stood in one place for three whole weeks. Finally, his prudent and decisive measures were crowned with the desired success: the plague stopped. The Russian army quickly moved to the borders of Guria, in passing captured the important fortress of Akhalkalaki, then Gertvis, made an incredibly difficult transition through the high mountain ranges, which were considered impassable, overcame the unbearable heat and approached Akhaltsikhe. At the same time, both pashas, who had come from Erzerum, appeared under its walls with 30,000 armies. Paskevich attacked them, utterly defeated both of them, scattered their troops through the forests, captured four fortified camps, all the artillery, and turned the guns recaptured from the enemy to Akhaltsikhe.

Field Marshal Ivan Paskevich

Founded by Caucasian daring men in mountain gorges, on rocks and cliffs, Akhaltsikhe, long before the Russian-Turkish war of 1828-1829, served as a brothel for violent freemen of different faiths and tribes, who found a safe refuge in it, was famous throughout Anatolia for the warlike spirit of its inhabitants, conducted an active trade with Erzerum, Erivan, Tiflis, Trebizond, had up to 50,000 inhabitants within its walls, and since it fell into the power of the Turks, for about three centuries I have not seen alien banners on the walls. Tormasov could not take it, and no wonder: Akhaltsikhe was defended by unusually solid and high palisades that surrounded the whole city, a fortress, a three-tiered fire of numerous artillery, houses built in the form of fortified castles, and the tested courage of the inhabitants, of which each was a warrior.

Confident in his abilities, Pasha Akhaltsikhe proudly replied to all proposals for surrender that the saber would solve the matter. Three weeks of fire from our batteries did not shake his stubbornness. Meanwhile, our meager reserves were depleted. It remained either to retreat, or to take Akhaltsikhe by storm. In the first case, one had to be wary of an unfavorable influence for the Russians on the minds of open and secret enemies; in the second, the entire corps could easily die in the fight against the enemy, five times as strong. The brave leader of the Russian Paskevich decided on the latter. On August 15, 1828, at 4 o'clock in the afternoon, the assault column, led by Colonel Borodin, went on the attack and, after incredible efforts, broke into Akhaltsikhe; but here a desperate battle awaited her; it was necessary to storm every house and pay dearly for every step forward. This one of the most glorious battles of the Russian-Turkish war of 1828-1829 lasted the whole night amid the fire that engulfed almost the entire Akhaltsikhe; several times the advantage leaned on the side of numerous enemies. Commander-in-Chief Paskevich with rare skill supported the weakening forces of his columns, sent regiments after regiments, brought his entire corps into action and triumphed: on the morning of August 16, 1828, the Russian banner of St. George was already fluttering on the Akhaltsikhe fortress.

Russian-Turkish war 1828-1829. Battles for Akhaltsikhe in 1828. Painting by J. Sukhodolsky, 1839

The victorious Paskevich hastened to calm the bloodshed, granted mercy and protection to the vanquished, established a government order consistent with their customs, and, restoring the ruined fortifications of Akhaltsikhe, turned it into a reliable stronghold of Georgia on the part of Asiatic Turkey. The conquest of Bayazet by a separate detachment at the foot of Ararat ensured the annexation of the entire Erivan region. Thus, in less than two months, with the most limited means, the will of the emperor was carried out: the enemy army, which threatened the Transcaucasian region with a devastating invasion, was scattered by Paskevich; the pashalyks of Kar and Akhaltsikhe were in Russian power.

Preparations for the 1829 campaign

The successes of Russian weapons in 1828 in Europe and Asia, on land and at sea, the occupation of two principalities, most of Bulgaria, a significant part of Anatolia, the conquest of 14 fortresses, the captivity of 30,000 people with 9 pashas, 400 banners and 1,200 guns - all this, it seemed, was to convince the sultan of the need to end the Russian-Turkish war and reconcile with the powerful emperor of Russia. But Mahmud remained as before adamant in hostility and, rejecting peace proposals, was preparing to resume the battle.

An unexpected event confirmed the Sultan's intention to continue the Russo-Turkish war. At the end of January 1829, our envoy in Tehran, the famous writer Griboyedov, was put to death with most of his retinue by violent mob; at the same time, the hostile disposition of the shah was revealed, who even began to concentrate his troops near the Russian borders, on the Araks. The Sultan hurried to start negotiations with the court of Tehran and no longer doubted the break between Persia and Russia. His hope was not fulfilled. Count Paskevich rejected a new Russo-Persian war. He let the heir to the throne, Abbas Mirza, know that the destruction of the imperial mission in Tehran threatened Persia with the most disastrous consequences, that a new war with Russia could even overthrow the Qajar dynasty from the throne, and that there was no other way to make up for the deplorable loss and avert the storm, how to ask for forgiveness from the Russian emperor for the unheard-of deed of the Tehran mob through one of the Persian princes. No matter how painful such a proposal was for Eastern pride, Abbas Mirza persuaded the Shah to agree, and Abbas's eldest son, Khozrev Mirza, in a solemn audience, in the presence of the entire court and the diplomatic corps, at the foot of the Russian throne, asked the sovereign emperor to consign the incident to eternal oblivion , which offended the Russian court as well as the Persian court. “The Shah’s heart was horrified,” said the prince, “at the mere thought that a handful of villains could break his alliance with the great monarch of Russia.” We could not wish for a better retribution: the prince was told that his embassy had dispelled every shadow that could darken the mutual relations between Russia and Persia.

Deprived of the assistance of the Shah, the sultan did not lose hope of turning the tide of the Russian-Turkish war of 1828-1829 and enlisted all his forces to fight against Russia. His army, concentrated in Shumla, was increased by several thousand regular troops sent from Constantinople, and the new Turkish vizier, the active and brave Reshid Pasha, was ordered to take Varna from the Russians at all costs and oust them from Bulgaria. A new seraskir with unlimited powers was also appointed to Erzurum; Gagki Pasha, a commander known for his art and courage, was sent to help him: they were instructed to arm up to 200,000 people in Anatolia, capture Kars and Akhaltsikhe, and defeat our Transcaucasian regions.

The Sovereign Emperor, for his part, strengthened the army stationed on the Danube, entrusted it, due to the illness of Field Marshal Wittgenstein, to the chief authorities of the Count Dibicha. Reinforcements were also assigned to the corps of Count Paskevich. Both generals were ordered to wage the Russian-Turkish war in 1829 as decisively as possible. They fulfilled the will of their sovereign in the most brilliant way.

Having crossed the Danube with the main army, in the spring of 1829, Count Dibich laid siege to Silistria, which we did not have time to take last year due to the early onset of winter. The commander-in-chief turned in that direction, both because the conquest of Silistria was necessary to ensure our operations across the Danube, and with the intention of luring the vizier out of Shumla. It was almost possible to guarantee that the active Turkish commander, taking advantage of the distance of the main Russian army, would not leave our detachments in peace, stationed in Pravoda and Pazardzhik, and would turn on them with most of his forces. The vision of the far-sighted leader was soon justified.

Battle of Kulevcha (1829)

In mid-May 1829, the vizier set out from Shumla with 40,000 of his best troops and laid siege to Pravody, occupied by General Kupriyanov, under the general command of General Roth, who distracted him with a stubborn defense and let the commander-in-chief know about the enemy’s exit from his impregnable position. Count Dibich was just waiting for this: having entrusted the siege of Silistria to General Krasovsky, he himself hastily moved to the Balkans with most of his army, walked without rest, skillfully concealed his movement, and on the fifth day stood in the rear of Reshid, thus cutting him off from Shumla. The Turkish vizier was not at all aware of the danger that threatened him and calmly engaged in the siege of Pravod; finally learning about the appearance of the Russians in his rear, he mistook them for a weak detachment from the corps of General Roth, who dared to block his way to Shumla, and turned his army to exterminate the small, in his opinion, enemy. Above all expectations, in the gorges of Kulevchi, Dibich himself met him on May 30, 1829. Reshid comprehended all the danger of his position, but did not lose courage and decided to break through the Russian army. He quickly and boldly led the attack at all points and met a formidable rebuff everywhere. In vain the Turks, with a fury of despair, rushed at our slender columns, cut into the infantry, crashed into the cavalry: the Russians were unshakable. The prolonged battle so exhausted both armies that around noon the battle seemed to subside of itself. Taking the opportunity, Dibich reinforced the tired soldiers with fresh regiments and, in turn, attacked the enemy. The battle resumed with a terrible cannonade from both sides; it did not hesitate long: from the fierce fire of our batteries, controlled by the chief of staff himself, General Tol, the enemy guns fell silent, the enemies trembled. At that very moment, Count Diebitsch moved forward his incomparable infantry, their formidable columns hit them with bayonets. The harmony and speed of the widespread attack made the Turks tremble: they fled and scattered in the mountains, leaving up to 5,000 corpses on the battlefield, the entire convoy, artillery and banners. The vizier barely escaped captivity with the speed of his horse and with great difficulty made his way to Shumla, where not even half of his army returned. The victor camped in front of him.

Trans-Balkan campaign of Dibich (1829)

The victory at Kulevcha had very important consequences for the course of the Russian-Turkish war of 1828-1829. Completely defeated, trembling for Shumla herself, the vizier, in order to protect her, drew to himself the detachments guarding the paths in the mountains, and thereby opened the Balkan gorges, and also weakened the coastline. Graph Dibich decided to take advantage of the enemy's oversight and was only waiting for the conquest of Silistria in order to cross the Balkans. She finally fell, brought by the activity and art of General Krasovsky to the point of impossibility to continue the defense. The commander-in-chief immediately transferred the corps that was besieging Silistria to Shumla and instructed Krasovsky to lock up the vizier in its strongholds; he himself, with other troops, quickly moved into the Balkan mountains. The advanced corps of Roth and Ridiger cleared the way of the enemy, knocked him out of all the places where he wanted to stop, captured the crossings on Kamchik from battle and descended into the valleys of Rumelia. Dibich followed them.

Field Marshal Ivan Dibich-Zabalkansky

Krasovsky, meanwhile, acted with such skill near Shumla that for several days Reshid Pasha took his corps for the entire Russian army, and then only learned about its movement beyond the Balkans, when it had already passed dangerous gorges. In vain did he try to strike her in the rear: the brave Krasovsky struck him himself and locked him up in Shumla.

Meanwhile, the Russian naval forces in the Black Sea and in the Archipelago, by order of the sovereign emperor himself, in accordance with the actions of the commander in chief, captured the coastal fortresses in Rumelia, Inadou and Enos and joined with the land army.

In the fruitful valleys of Rumelia, Dibich's Trans-Balkan campaign - the most heroic deed of the Russian-Turkish war of 1828-1829 - was likened to a solemn procession: small detachments of Turkish troops were unable to stop him, while the cities surrendered one after another almost without resistance. The Russian army maintained strict discipline, and the inhabitants of Rumelia, convinced of the inviolability of their property and personal safety, willingly submitted to the victor. So Dibich reached Adrianople, the second capital of the Turkish Empire. The pashas who commanded it wanted to defend themselves and lined up an army. But numerous crowds of people, avoiding bloodshed, left the city with greetings to meet our soldiers, and the populous Adrianople was occupied by the Russians on August 8, 1829 without a fight.

Dibich stood in Adrianople, leaning on the right flank on the archipelago squadron, on the left on the Black Sea fleet.

Campaign of 1829 in Transcaucasia. Capture of Erzerum by Dibić

An equally cruel blow was inflicted by the Russian Turks in Asia. Fulfilling the order of the sovereign emperor, who demanded the most decisive action, in the spring of 1829, Count Paskevich concentrated his entire corps in the vicinity of Kars, comprising up to 18,000 people, including Muslims recruited in areas that had been subdued by our weapons shortly before. The brave Russian leader planned to immortalize the memory of this Russian-Turkish war with a feat worthy of his glory - the capture of the capital of Anatolia, rich and populous Erzurum.

Seraskier of Erzerum, for his part, gathered an army of 50,000 with the intention of taking away from us the conquests of the past year and invading our borders. For this purpose, he sent his comrade Gagki Pasha to Kars with half the army; the other half he led himself to help him. Count Paskevich hurried to smash them one by one before they had time to unite, crossed the high Saganlungsky ridge, covered with snow, and met Gagki Pasha, who was standing in a fortified camp, on an impregnable place. There was a seraskir ten versts from him. The commander-in-chief rushed to the latter and, after a short battle, scattered his army; then he turned on Gagki Pasha and took him prisoner. Two enemy camps, carts, artillery were the trophies of this victory, famous in the annals of the Russian-Turkish war of 1828-1829.

Not giving the enemies time to recover from the horror, Paskevich quickly moved forward and a few days later appeared under the walls of Erzurum. Seraskyr wanted to defend himself; but the inhabitants, having been confirmed by repeated experiments in the magnanimity of the winner, in the inviolability of their property and their charters, did not want to experience the fate of Akhaltsikhe and submitted voluntarily. Seraskier surrendered to prisoners of war. The Turkish army did not exist. In vain, the new seraskir, sent by the Sultan, wanted to oust the Russians from Erzurum and gathered scattered troops: Paskevich struck him within the walls of Bayburt and was already intending to penetrate further into Anatolia, when the news of the peace that had ended the Russian-Turkish war of 1828-1829 stopped his victorious march.