Routes of Viking campaigns in the 7th - 11th centuries. Vikings - the world of the Middle Ages. Viking armor and weapons

Vikings and Ancient Rus'

The story of a leading expert on the Viking Age in Eastern Europe, Doctor of Historical Sciences Elena Aleksandrovna Melnikova

Wall newspapers of the charitable educational project “Briefly and clearly about the most interesting” are intended for schoolchildren, parents and teachers of St. Petersburg. Our goal: schoolchildren– show that acquiring knowledge can be a simple and exciting activity, teach how to distinguish reliable information from myths and speculation, tell that we live in a very interesting time in a very interesting world; parents– help in choosing topics for joint discussion with children and planning family cultural events; teachers– offer bright visual material, rich in interesting and reliable information, to enliven lessons and extracurricular activities.

We choose important topic, are looking for specialist, who can open it and prepare the material, adapt its text for a school audience, we put it all together in a wall newspaper format, print a copy and deliver it to a number of organizations in St. Petersburg (district education departments, libraries, hospitals, orphanages, etc.) for free distribution. Our resource on the Internet is the wall newspaper website, the website where our wall newspapers are presented in two types: for self-printing on a plotter in full size and for comfortable reading on the screens of tablets and phones. There are also group VKontakte and a thread on the website of the St. Petersburg parents Littlevan, where we discuss the release of new newspapers. Please send your comments and suggestions to: [email protected] .

Mikhail Rodin – scientific journalist, author and presenter of the popular science program “Homeland of Elephants” (photo antropogenez.ru) and Elena Aleksandrovna Melnikova – Doctor of Historical Sciences, head of the Center “Eastern Europe in the Ancient and Medieval World” of the Institute of General History of the Russian Academy of Sciences (photo iks .gaugn.ru).

Alas, it rarely happens that a famous scientist is also a popularizer. After all, it is necessary not only to “translate” dry scientific information as accurately as possible into a language understandable to the general public. And do this also in a fascinating, imaginative way, with vivid examples and illustrations. Such independent and very labor-intensive tasks are solved by a scientific journalist - an intermediary between scientists and society. As a rule, he has a higher specialized education, his own audience of interested readers (listeners or viewers) and, most importantly, an impeccable reputation in the scientific community (otherwise scientists simply will not talk to him).

We are pleased to begin cooperation with such a professional – a science journalist Mikhail Rodin and his popular science program " Homeland of elephants"on the radio "Moscow Speaks". Here they “debunk historical myths and talk about facts that are obvious to scientists, but for various reasons unknown to the average person.” This issue of our wall newspaper was prepared based on materials from two programs: “The Norman Question” and “Prehistory of Rus'”.

Mikhail Rodin's interlocutor was Elena Aleksandrovna Melnikova– Doctor of Historical Sciences, head of the Center “Eastern Europe in the Ancient and Medieval World” of the Institute of General History of the Russian Academy of Sciences, a leading researcher in Russian science (and recognized by the world scientific community) of Russian-Scandinavian relations in the early medieval period.

History of the Norman Question

1. Catherine I (1684–1727) - Russian empress, second wife of Peter I. Artist Jean-Marc Nattier, 1717 (State Hermitage Museum).

2. Participants in the first dispute between “Normanists” and “anti-Normanists”: Gottlieb Bayer - German historian, philologist, one of the first academicians of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences, researcher of Russian antiquities. Gerard Miller is a Russian historiographer of German origin. Full member of the Imperial Academy of Sciences and Arts, leader of the Second Kamchatka Expedition, organizer of the Moscow Main Archive. Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov is a Russian natural scientist, encyclopedist, chemist and physicist, full member of the St. Petersburg and honorary member of the Swedish Academy of Sciences.

3. Catherine II in Lomonosov’s workshop. Painting by Alexey Kivshenko, c. 1890.

4. Nikolai Mikhailovich Karamzin. Writer, historian, author of “History of the Russian State.” Portrait by Alexey Venetsianov, 1828.

The “Norman Question” is the name given to the two-century debate between “Normanists” and “anti-Normanists.” The first claim that the Old Russian state was created by the “Normans” (immigrants from Scandinavia), while the second do not agree with this and believe that the Slavs managed it themselves. Looking ahead, we note that modern scientists, when assessing the role of the Scandinavians in the formation of the Old Russian state, take a “moderate” position. However, first things first.

The “Norman Question” first began to be discussed in Russia in the 18th century. In 1726, Catherine I invited major German historians: Gottlieb Bayer, Gerhard Miller and a number of others. Their works were based on the study of ancient Russian writing, primarily the Tale of Bygone Years. Miller wrote a review of early Russian history that was discussed at the Academy of Sciences.

The formation of a state at that time was understood as a one-time act. Moreover, then they thought that one person could do it. And the only question was who exactly did it. From the Tale of Bygone Years it directly followed that the Scandinavian Rurik came and single-handedly organized the state. And Miller outlined all this in his review. Lomonosov spoke out sharply against this concept. His patriotic feelings were offended: what, the Russian people themselves cannot organize a state? What does some Scandinavian have to do with this? A very heated debate broke out on this issue, which well illustrated the process of formation of national identity. Gradually, this dispute died down, and Karamzin (who received the title of official historiographer from Emperor Alexander I in 1803) wrote about the arrival of the Scandinavians and their participation in the formation of the state quite calmly.

A new outbreak of anti-Normanism was associated with “Slavophilism.” This trend of Russian social thought, which took shape in the 40s of the 19th century, substantiated the special, original path of Russia. Within the framework of this concept, the recognition of the Scandinavians as participants in the processes of state formation was unacceptable.

At the end of the 19th century, extensive archaeological research began, which showed the presence of Scandinavians in many places. The theoretical foundations of the origin of the state also changed: it became clear that this was a long process, and not at all a one-time act. That the Slavic tribes developed for a long time and intensively, and the arrival of the Scandinavians only strengthened the processes of state formation, which were already in full swing in the East Slavic world. Regardless of what Rurik's ethnicity was, a state would still have been formed. At the end of the 19th – first half of the 20th century, the presence of the Scandinavians and their active role in the formation of the ancient Russian state was calmly spoken to by the Scandinavian elite who led these processes.

But at the end of the 1940s, a tragic struggle against cosmopolitanism broke out: any mention of foreign influence was prohibited. Some historians began to look for other options for explaining ancient Russian history, and the idea of the independent development of the Eastern Slavs prevailed. Naturally, development completely isolated from the outside world is impossible in principle. Development occurs only when there is mutual influence and interaction between different peoples. However, at that difficult time, the “party line” was put at the forefront. The Normans were expelled from Russian history. In books from the 1950s, Scandinavians are generally not mentioned at all. Although excavations continued in those places where Scandinavians made up almost the bulk of the population.

Now there is agreement again in the scientific community. Most scientists consider both “Normanism” and “anti-Normanism” to be deeply outdated and absolutely not productive from a scientific point of view concepts. Historians, archaeologists, linguists (both Western - English, German, Swedish - and Russian) understand each other perfectly on this. There are a lot of questions, but they are of a purely scientific nature. For example, what language did the Scandinavians speak in Eastern Europe? How did the Scandinavian language mix with Slavic? How did those Scandinavians who reached Byzantium become acquainted with Christianity? How was this reflected in the culture of Scandinavia itself? These are very interesting questions of the cultural interchange of different peoples in the vast expanses of Eastern Europe during the birth and formation of Ancient Rus'.

Source problem

5. Portraits of the Rurikovichs (illustration from the book “Ancient and Modern Costume” by Giulio Ferrariu, 1831).

6. Oleg shows little Igor to Askold and Dira (miniature from the Radziwill Chronicle, 15th century).

7. Oleg’s campaign with his squad to Constantinople. Miniature from the Radziwill Chronicle, 15th century.

8. “The funeral funeral at the grave of Prophetic Oleg.” Painting by V. M. Vasnetsov, 1899.

9. “Oleg nails his shield to the gates of Constantinople.” Engraving by F. A. Bruni, 1839.

10. “Oleg at the horse bones.” Painting by Viktor Vasnetsov, 1899.

11. “Yaroslav the Wise and the Swedish princess Ingigerda.” Painting by Alexey Trankovsky, early 20th century.

12. Daughters of Yaroslav the Wise and Ingigerda: Anna, Anastasia, Elizabeth and Agatha (fresco in the St. Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv).

13. Yaroslav the Wise. Drawing by Ivan Bilibin.

Neither in Rus' nor in Scandinavia in the 9th – early 11th centuries there was a developed written language. There was a runic script in Scandinavia, but it was used very little. Writing came to Rus' along with Christianity at the end of the 10th century. Old Russian written monuments were written, at best, in the 30s of the 11th century. And what has come down to us - “The Tale of Bygone Years” - was compiled at the beginning of the 12th century. It turns out that during the 9th - first half of the 11th centuries there were only stories, epic narratives, songs about events that reached the chronicler. The stories were overgrown with a variety of folklore motifs. Oleg's campaign against Constantinople is full of them - he rejects poisoned wine (for which he was nicknamed the Prophetic), and puts ships on wheels. The chronicler has his own idea of history, based on Byzantine models. And, accordingly, it also transforms these myths. For example, there were several legends about Kiy, the founder of Kyiv: he was both a hunter and a carrier, but the chronicler makes him a prince.

Along with the Tale of Bygone Years, we have a number of monuments that were created in those regions of the world where writing existed for a long time. This is, first of all, Byzantium with its ancient heritage, the Arab world, and Western Europe. These written sources allow us to look at ourselves “from the outside” and fill many gaps in our knowledge of history. For example, it is known that Yaroslav the Wise was related to almost all the ruling houses of Europe. One of his sons, Izyaslav, was married to the sister of the Polish king Casimir I. Another, Vsevolod, to a Byzantine princess, a relative, perhaps a daughter, of Emperor Constantine IX Monomakh. Elizabeth, Anastasia and Anna were given in marriage to the kings. Elizabeth - for the Norwegian Harald the Harsh, Anastasia - for the Hungarian Andrew I, and Anna - for the French Henry I. Probably, Yaroslav's son Ilya was married to the sister of the Danish and English king Knut the Great. Yaroslav, as we know from Scandinavian sources, was married to the Swedish princess Ingigerda, who apparently received the name Irina in Rus'.

But our chronicles say practically nothing about this. This is why it is so important to study all available sources. And evaluate them critically. For example, a scientist does not have the right to read “The Tale of Bygone Years” word for word and believe everything that is written there. You need to understand: who wrote this, why, under what conditions, where he got the information from, what was going on in his head, and only taking this into account to draw conclusions.

"Headache" of Europe

14. Map of the main Viking campaigns and places of their settlements (ill. Bogdangiusca).

15. One-eyed Odin (the supreme god in German-Scandinavian mythology, master of Valhalla and lord of the Valkyries) and his ravens Hugin and Munin (“thinking” and “remembering”). Illustration from an 18th-century Icelandic manuscript (medievalists.net). According to the Vikings, after each battle, Valkyries flew to the battlefield and took the dead warriors to Valhalla. There they are engaged in military training in anticipation of the end of the world, in which they will fight on the side of the gods.

16. Title page of the Prose Edda with images of Odin, Heimdall, Sleipnir and other heroes of Scandinavian mythology. 18th century manuscript (Icelandic National Library).

17. Helmets of the early Viking Age from boat burials. Wendel helmet of the 7th century (Sweden, ill. readtiger.com), a spectacular reconstruction of the helmet of an Anglo-Saxon king at the turn of the 6th and 7th centuries (British Museum, ill. Gernot Keller), and an excellently preserved York helmet of the 8th century (England, ill. yorkmuseumstrust.org. uk). Simple Vikings wore simpler helmets or leather hats made of thick cowhide. Contrary to popular belief, Vikings never wore horned helmets. Ancient horned helmets are known, but they were worn by the Celts of pre-Viking times (IV–VI centuries).

18. “Varangian Sea”. Painting by Nicholas Roerich, 1910.

19. Rune stone placed in memory of Harald, brother of Ingvar the Traveler. State Administration for the Protection of Cultural Monuments (ill. kulturologia.ru).

20. Viking statue on the shore of the Trondheim fjord in Norway (photo by Janter).

In the middle of the first millennium AD, the most warlike part of the tribes living in the territory of modern Sweden, Denmark and Norway began to launch sea raids on their neighbors. There are many reasons for this behavior - overpopulation, depletion of arable land, and climate change. The belligerence of the Scandinavians themselves, as well as their successes in shipbuilding and navigation, played a significant role. By the way, the attacks were not always of a predatory nature - if the valuables could not be taken away, they were exchanged or bought.

Latin sources called the Scandinavian sea robbers “Normans” (“northern people”). They were also known as “Vikings” (according to one version, “people of the bays” from Old Norse). In Russian chronicles they were described as “Varangians” (from Old Norse - “those who take an oath”, “mercenaries”; from the word “oath”). “Save us, Lord, from the plague and the invasion of the Normans!” - with these words in the Viking Age (late 8th - mid 11th centuries) prayers traditionally began throughout Western Europe, from the North to the Mediterranean Sea.

The first wave of Scandinavian expansion began back in the 5th century, when the Angles and Jutes (tribes who lived on the Jutland Peninsula) and the Saxons (who lived at the base of the Jutland Peninsula) raided England and settled in the captured territory. Scandinavians specialize in military activities and become the best warriors in Europe. Neither the powerful Frankish state of the descendants of Charlemagne, nor the English state could resist them. London is under siege. All of central and eastern England is captured. An area of Danish law is formed there. “A large pagan army,” says the Anglo-Saxon chronicle, “first plundered the land, and then some of it separated and decided to settle here.”

In 885, a huge Viking fleet kept Paris under siege for a whole year. The city is saved only by a huge sum - 8 thousand pounds of silver (a pound - 400 grams) - paid to the Scandinavians so that they would leave Paris. The territory of northwestern France was a favorite place for robbery among the Vikings from the very beginning of the 9th century. The city of Rouen was destroyed, the entire surrounding area was devastated.

Viking ships

21. Ship from Oseberg (southern Norway, first third of the 9th century). Excavations of 1904–1905 (ill. Viking Ship Museum, Norway).

22. The ship from Oseberg in the museum after restoration (ill. Viking Ship Museum, Norway).

23. One of the five heads of mythical animals found during excavations of the Oseberg ship (Museum of Cultural History, University of Oslo, Norway / Sonty567).

24. Mask found during excavations of the Oseberg ship (Viking Ship Museum, Bygdoy).

25. “Gokstad ship” - a Viking longship, used as a funeral ship in the 9th century. Discovered in 1880 in a mound on the shores of Sandefjord in Norway. Its dimensions: length 23 m, width 5 m. Rowing oar length – 5.5 m. Model (photo by Softeis).

26. Drakkar - a Norman warship. Detail of the famous Bayeux Tapestry. The images, embroidered onto 70 meters of linen, tell the story of the Norman Conquest of England in 1066.

27. Viking ships. Reconstruction of the external appearance based on surviving elements. Information board on the shore of the fjord (ill. Vitold Muratov).

28. Image of warriors in a longship on the Stura Hammar stone on the island of Gotland, fragment (Berig)

29. The Byzantine fleet repels the Russian attack on Constantinople in 941 (miniature from the Chronicle of John Skylitzes).

The entire life of the Scandinavians was connected with navigation, so shipbuilding technology was very developed. Moreover, this happened not only among the Vikings, but also long before them - in the Bronze Age. Petroglyphs in southern Sweden contain hundreds of images of ships. Since the beginning of our era, there have been finds of ships and their remains in Denmark. The design of the ship was based on a beam, which was a keel. Or a very large tree trunk was hollowed out.

Then the sides were sewn on top, so that one board overlapped the other. These boards were fastened with metal rivets. At the top there is a gunwale, in which recesses were made for rowlocks and oars, because the ships were sailing and rowing. The sail appeared only in the 6th–7th centuries; before that there were only oared ships, but oarsmen remained until the very end of the Viking Age. The mast was strengthened in the middle.

During the Viking Age, ships already differed in purpose. Ships for military operations (drakkars) were narrower and longer, they had greater speed. And ships for trading purposes (knorrs) were wider and more cargo-capacity, but slower and less maneuverable. The peculiarity of Viking ships is that the stern and bow were made the same in configuration (in modern ships the stern is blunt and the bow is pointed). Therefore, they could swim to the shore with their bow and sail away with their stern, without turning around. This made it possible to make lightning-fast raids - they sailed, plundered, and quickly loaded onto ships and back.

A beautiful restored example - the ship from Oseberg - is just that. By the way, its stem, made in the form of a curl, is removable. And during attacks, to intimidate the enemy, a dragon’s head was put on the stem.

Vikings in the service of the local nobility

30. Duchy of Normandy in the 10th and 11th centuries (Vladimir Solovjev).

31. Rollon (Hrolf the Pedestrian) in an 18th-century engraving. Rollon is a Franco-Latin name by which one of the Viking leaders Hrolf was known in France. He was nicknamed "The Pedestrian" because no horse could carry him, he was so big and heavy. First Duke of Normandy, founder of the Norman dynasty.

32. Negotiations between Rollon and the Archbishop of Rouen (Bridgeman Art Library, 18th-century engraving).

33. Baptism of Rollo by the Archbishop of Rouen (Library of Toulouse, medieval manuscript).

34. Frankish king Charles the Simple, giving his daughter to Rollo. Illustration in a 14th-century manuscript from the British Library.

35. Head of the statue of Rollo in the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Rouen (Giogo).

36. “A Thracian woman kills a Varangian” (miniature from the “Chronicle of John Skylitzes”).

37. Varangian detachment in Byzantium. Reconstruction drawing of the late 19th century (New York Public Library).

38. A mercenary detachment of Varangian guards in Byzantium (miniature from the “Chronicle of John Skylitzes”).

From the end of the 9th century, some of the Viking troops began to enter the service of the Frankish and English kings as vassals. Sometimes they later went back, and sometimes they remained at court forever. By the beginning of the 10th century, virtually the entire northern part of the Seine was occupied by individual Viking detachments. The leader of one of them was Rolf “Pedestrian” (he was so called because he was so heavy that not a single horse could carry him). French sources called him Rollon. In 911, the Emperor of the Frankish Empire, Charles the Simple, entered into an agreement with Rollo. Charles provided Rollon with a territory centered in Rouen, and Rollon in return ensured the protection of the Frankish territories and Paris, and went on predatory campaigns into the territories of Charles’s opponents. This is how the future Duchy of Normandy (“land of the Normans”) arose - now a region in northwestern France.

It is known that already at the end of the 10th century, a Norman duke was looking for a Danish teacher for his son. That is, the newly arrived Scandinavians had almost forgotten their native language by this time. And just 150 years later, during the time of the Duke of Normandy, William the Conqueror, the Normans spoke only French, mastered French culture - in fact, completely mixed with the local population, becoming French. All that was left of the conquerors was the name. France was a large state with established traditions, and the Normans found it easier to fit into ready-made structures than to build new ones. This ensured their rapid “dissolution” or, as scientists say, “assimilation”.

A similar story, by the way, happened with Bulgaria. The territory of this country was previously inhabited by Slavic tribes, which were attacked by the Turks. The Bulgarian kingdom arose, led by Khan Asparukh. Gradually, the invaders dissolved in the Slavic environment, adopted the Slavic language, culture, adopted Christianity, but left in memory of themselves the Turkic name - Bulgaria.

You can also mention the Germanic tribe of the Franks, which captured Gaul. Soon the Franks completely disappeared there, leaving the captured country as a legacy of the German name - France.

“From the Varangians to the Arabs”

39. The main trade routes of the Varangians (electionworld).

40. Volga trade route: Baltic Sea – Neva – Lake Ladoga – Volkhov River – Lake Ilmen – Msta River – Volok by land – Volga – Caspian Sea (top-base shadedrelief.com).

41. Arab conquests by the middle of the 7th century (Mohammad adil).

42. “Dragged by drag.” Painting by Nicholas Roerich, 1915.

43. “Funeral of a noble Russian.” Painting by Henryk Semiradsky (1883) based on Ibn Fadlan's story about his journey to the Volga. In 921, he met the Rus in Bulgaria and was present at their funeral rites (State Historical Museum).

In the 7th century, the southern coast of the Mediterranean Sea up to Spain was conquered by the Arabs. The trade routes that had passed here for a long time were blocked. Intensive trade between Central and North Sea Europe with the countries of the East ceased. The search for a new path began, and the Scandinavians found themselves in the very center of it. The path passed through the Baltic Sea, through the Neva, Ladoga, along the Volkhov River to Ilmen, along Msta to the Volga, from where a passage further into the Arab world was gradually discovered. The main trade took place in the city of Bulgar at the confluence of the Volga and Kama.

Thus a powerful new trans-European trade route was established. Participation in this trade was very profitable. Arab silver and gold flowed along the Baltic-Volga route to Scandinavia, primarily to Gotland, reaching Denmark and further to England and France.

The establishment of this trade route was of enormous importance for Scandinavia itself. The processes of social and property stratification intensified, which led to the strengthening of the power of the konungs (supreme rulers). Accordingly, the processes of formation of the Scandinavian states intensified. In the 7th-8th centuries, the North Sea coast (both Frankish and English) was dotted with shopping centers.

On the eastern coast of the Baltic, the first Scandinavian settlements, apparently from the island of Gotland, appeared in the 5th century. On the territory of Lithuania there was a large trade and craft settlement of Grobinya. A large Scandinavian burial ground has been discovered on the island of Saaremaa. In the Gulf of Finland, on the island of Bolshoi Tyuters, there was also a Scandinavian camp. Traces of their presence were also found in the north of Lake Ladoga.

Scandinavians were attracted to Eastern Europe by furs. Let's say that the squirrel was found in Scandinavia, but the ermine and marten were not. Only in our taiga.

Staraya Ladoga

44. “Overseas Guests”, painting by Nicholas Roerich, 1901 (Tretyakov Gallery).

45. Fortress in Staraya Ladoga (photo by Andrey Levin).

46. Items from the mound in the Plakun tract: 1 – silver beads; 2-13 – glass beads; 14 – melted bronze; 15 – melted silver; 16 – fragment of an iron buckle; 7 – copper chain; 18-20 – bolts; 21 – iron plate; 22-25 – parts of iron forging; 20 – shale whetstone (ladogamuseum.ru)

47. Rune stone in memory of the Viking who fell “in the east in Gardah” (photo by Berig).

48. Viking burial on the bank of a river in Eastern Europe (Sven Olof Ehren, kulturologia.ru).

The penetration of the Scandinavians onto the shores of Lake Ladoga began in the 7th century. In the middle of the 8th century, Ladoga appeared - a trading settlement on the North Sea-Baltic route. Here, in the area of Lake Ladoga, on the Volkhov River, north of Lake Ilmen, a center arises that concentrates trade activities and opens the way to Eastern Europe for the Scandinavians.

Just like in Western Europe, there is a colossal flow of values here. The volume of trade is reflected in the number of hoards of silver Arab coins. The first two treasures (of those discovered) in Eastern Europe in Ladoga date back to the 780s. At the turn of the 8th-9th centuries, treasures were formed on the territory of modern Peterhof and on the island of Gotland. During the 9th–10th centuries, about 80 thousand Arabic coins were hidden on Gotland alone, and recently a treasure weighing 8 kilograms of silver was discovered there.

This area is inhabited by Finns and Slavs who came from the south, and controlled by Scandinavians. There is a mutual fusion, a synthesis of multicultural elements. The Finns hunt fur-bearing animals, while the Slavs engage in agriculture and craft activities. The local nobility receives furs as tribute and exchanges them with visiting Scandinavians for silver, gold and luxury goods. And it is more convenient for the Scandinavians to receive bales of fur collected by the local nobility.

Settlements are formed along trade routes where merchants can stop, repair ships, trade, and stock up on food. In order for the trade route to work normally, it needs to be controlled: first of all, to ensure security. This is how a “polity” arises in the region between Ladoga and Ilmen: not yet a state, but no longer a tribal entity. The first polity on the territory of the Eastern Slavs.

The traces of the Scandinavians here are very clear: the construction of houses, ceramics, jewelry, weapons, household items and, of course, burials according to the Scandinavian funeral rite, which reflected their beliefs and ideas about the afterlife. In Staraya Ladoga, in the Plakun tract, there is a large burial ground of the 9th century. Everything in the burials there - both the funeral rite and all the objects - are truly Scandinavian. Ladoga, the largest center of the early Middle Ages, has been well studied by archaeologists, and research is still ongoing.

The oldest strata date back to the 750s, and dendrochronology (determining time by tree rings) is very helpful. One of the oldest buildings was a Scandinavian craft workshop. Jewelry and blacksmithing tools found there are clearly of Scandinavian origin. From the middle of the 8th to the middle of the 9th century, Ladoga was the only major center in this region. A polity is formed around it, which is ruled by the Scandinavians, but which includes both the Slavic and Finnish populations. The same polity in which the power of the legendary Rurik is established. Here a common Finno-Slavic-Scandinavian zone arises, and here the name “Rus” appears.

The word "Rus"

49. Viking Boats (12th century miniature from the Life of St. Edmund, Bridgeman Images)

The word "Rus" comes from the Old Norse word "roser" or "rodsman", which means "rowers". The Scandinavians who came here called themselves oarsmen. This is the self-name of those bands who went on a journey. The word is reflected in the Finnish language as “rootse”, in Estonian – “rotse”, it exists in all Baltic-Finnish languages. In modern Finnish this is what Swedes are called. The long Scandinavian "o" in the word "rhods" is rendered in Finnish as "oo": "rootse". There is a whole series of such words. In the same way, we are talking about the pattern of transfer of the Finnish “rootse” into the Old Russian word “Rus”.

The etymology of the name Rus from Finnish (and in Finnish - from Scandinavian) is the most substantiated and accepted by most researchers.

It should be noted that linguistics, the science of language, is a very strict discipline. She explores clear laws of language change that are comparable to mathematics. Therefore, such reasoning as: “the prototype of the word “Rus” is the name of the Ros River in the Middle Dnieper region” is erroneous. Such an Iranian root (“light”, “brilliant”) really existed. But this Iranian “o” cannot in any way turn into the Old Russian “u”, because they go back to different Indo-European vowels.

“From the Varangians to the Greeks”

50. Dnieper trade route: Baltic Sea – Neva – Lake Ladoga – Volkhov River – Lake Ilmen – Lovat River – Portage by land – River Western Dvina – Portage by land – Dnieper – Black Sea (top-base shadedrelief.com).

51. “Varangian saga - the path from the Varangians to the Greeks.” Painting by Ivan Aivazovsky, 1876.

52. One of three “Ulfbert” swords found on the territory of Volga Bulgaria (Dbachmann).

Trade along the Volga route was very profitable. However, it was complicated by the fact that in the lower reaches of the Volga there was the Khazar Khaganate, which did not want to have competitors in the form of Scandinavian traders. And, accordingly, in the 9th century other routes to the south opened. There is a gradual development of the Dnieper route “from the Varangians to the Greeks.” In the 10th century, the Dnieper route (from the Baltic along the Neva, Ladoga and Volkhov to Lake Ilmen, along the Lovat River with portage to the Dnieper and further to the Black Sea) began to play a greater role than the Volzhsky. Because by the end of the 10th century, the silver mines in the eastern part of the Caliphate were exhausted, and the flow of silver dried up.

Since there is cultural exchange in such mixed settlements, they develop intensively. During the 9th-10th centuries, the network of settlements moved east. In the largest trade and craft complex of Gnezdovo near Smolensk, burials according to the Scandinavian rite are known, but the pots are Slavic and the decorations are partly Scandinavian, partly Slavic. In the Yaroslavl Volga region, in the large center of Timirevo, Finnish things are found in burials together with Scandinavian ones.

At the same time, other similar communities arose nearby, about which we know less. This is primarily the middle Dnieper region: on the right bank there is the Drevlyan polity with its princes; on the left bank are the northerners, also a highly developed Slavic group in socio-political terms. Polotsk was also located on the trade route from the Baltic to the Dnieper along the Dvina. In Polotsk in the 70s of the 10th century there was a Scandinavian ruler named Rogvolod, whose daughter became the wife of Prince Vladimir.

They, too, would have developed their own states if Scandinavian expansion from the north, led by Oleg, had not spread to the Dnieper region, and then, throughout the 10th century, the systematic subjugation of the Slavic polities began. The Scandinavians gradually began to move along trade routes towards Kyiv.

The overwhelming majority of modern historians associate the emergence of the Old Russian state with the unification of two pre-state formations: the northern one with the center in Ladoga and the southern one with the center in Kyiv.

At first, the sources clearly separate the Rus and the Slavs. Ibn Ruste, an Arab author, described the situation in the 9th century: “As for the Rus, they have a king called Khakan-Rus. They approach the Slavic settlements on ships, disembark and take them prisoner. They have no arable land, and they live only on what they bring from the land of the Slavs. Their only occupation is trading in sables, squirrels and other furs... When their son is born, he, the Russian, gives the newborn a naked sword, puts it in front of him and says: “I am not leaving you any property as an inheritance, and you have nothing.” except what you will gain with this sword." And here is what Ibn Ruste writes about the Slavs: “The country of the Slavs is flat and wooded. They sow most of all millet... When the harvest time comes, they take the millet grains into a ladle, raise it to the sky and say: “You, Lord, who give us food, give it to us in abundance!” Arab travelers and writers were clearly aware of this opposition.

On the banks of the Dnieper

53. The Patriarch of Constantinople lowers the robe of the Virgin Mary into the waters of the Bosphorus, pacifying the belligerence of the Rus (860). Radziwill Chronicle.

54. Mounds in Gnezdovo. The Gnezdovo archaeological complex is the largest burial mound of the Viking Age in Eastern Europe, a key point on the trade route “from the Varangians to the Greeks.” Once there were about 4,000 mounds and several fortified settlements. In 1868, during the construction of the railway, a large treasure was discovered here, objects of which can be seen in the Hermitage (photo gnezdovo-museum.ru).

55. The handle of a sword of the “Carolingian type” of the mid-10th century from Gnezdovo (gnezdovo-museum.ru).

56. Image of a Carolingian sword (Stuttgart Psalter, c. 830). Carolingian sword, or Carolingian-type sword (also often referred to as a “Viking sword”) is a modern designation for a type of sword that was widespread in Europe during the early Middle Ages.

57. Treasure of the 10th–11th centuries, found in Gnezdovo in 1993 (kulturologia.ru).

58. Treasure from the 10th century, found in 2001 in Gnezdovo. Silver jewelry and oriental coins - dirhams (from the collection of the Historical Museum) were hidden in a clay pot.

59. Treasure of the 10th–11th centuries, found on the banks of the Dnieper (kulturologia.ru).

The appearance of the Scandinavians in the Middle Dnieper region was immediately noticed by their western and southern neighbors. The first mention of the name “Rus” (“Ros” in the Byzantine sound) comes from the Western European source “Bertinian Annals”. Under the year 839, Prudentius, the historiographer of the Emperor of the German Empire, Louis the Pious, wrote that ambassadors from the Byzantine Emperor Theophilus came to Louis, and with them appeared certain people whom Theophilus asked Louis to let through so that they could return home safely; They were in Constantinople, but they could not return back the same way, because the fierce tribes would not let them in. Their people are called “ros”, and their king, called Khakan, sent them to Theophilus, as they assured, for the sake of friendship. But Louis didn’t like something about these dews. Therefore, having investigated the situation, the emperor learned that they were from the people of the Swedes (Swedes) and, considering them more likely to be scouts both in Byzantium and Germany than ambassadors of friendship, he decided to detain them until it was possible to find out for certain whether they came with pure intentions or No. It is unknown what the results of the investigation were. This is the first recording of the name “ros” in written sources.

Then they are mentioned many times in Byzantine sources. One of the most important references is the year 860, when the boats of the “godless dews” ended up at the walls of Constantinople. And only the “miracle of the Mother of God,” whose robe Patriarch Photius lowered into the Golden Horn, saved him. It was a huge flotilla that plundered the outskirts of Constantinople and caused a sensation in southern Europe. It was the first time Europeans encountered this extremely dangerous people.

In the middle of the 10th century, the Byzantine emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus describes a trip to Constantinople on one-tree boats from Rus'. This is chapter 9 of the treatise “On the Administration of the Empire,” one of the most important sources on the formation of the ancient Russian state. He describes the Russians who are concentrated in Kyiv. This is the military elite that trades with Constantinople, bringing goods there - tribute, which they collect from the Slavic tribes - "Slavini", as Constantine calls them. He lists these slaviniyas. That is, we know that in the middle of the century the Drevlyans, Northerners, Dregovichs, and Krivichis were subject to the Kyiv dews. This is the Middle and Upper Dnieper region - a strip that connects the Ladoga-Ilmen region with the Middle Dnieper region.

This is an already emerging state with a certain territory and structure. According to Constantine, there are several archons in Kyiv (among which one stands out) who travel around to collect tribute.

There is another wonderful source - Russian-Byzantine treaties. Both in the West and in the East, the Scandinavians who settled in these territories entered into treaties with the rulers. We talked about Rollon's agreement with Karl Prostovaty. The same one was concluded a little earlier in England between the ruler of Wessex and the leader of the Scandinavians.

The Rus, who settled in Kyiv, after campaigning against Byzantium, proceeded to establish diplomatic relations. In 907 or 911 (interestingly, the agreement with Rollo was also 911), after the successful campaign of the Kyiv prince Oleg, a trade agreement was concluded with Byzantium. It contains many articles on how to trade, where merchants come, and where they stay. They are settled in the Saint Mama quarter on the other side of the Golden Horn. They can leave this very quarter in numbers of no more than 50 people: the Byzantines are afraid that their military detachment will be too large. The next treaty of 944, concluded under Prince Igor, stipulates that the prince must give them letters of safe conduct, from which the Byzantine authorities can learn that they arrived legally and do not intend to engage in robbery. In the treaty, Igor is called the Grand Duke, he has at hand the bright princes, those whom Constantine calls archons. Hierarchy within the elite is an important indicator of state formation.

Fusion of cultures

60. Idol (presumably Scandinavian) holding his beard. Kurgan “Black Grave” in Chernigov, 10th century (historical.rf).

61. Silver frame of a drinking horn. Mound “Black Grave” in Chernigov, 10th century (studfiles.net)

62. Treasure from the 11th century weighing 12.5 kg, found in Smolensk in 1988. Its coinage consists of more than 5,400 Western European denarii and 146 eastern dirhams (muzeydeneg.ru).

63. Trade negotiations in the country of the Eastern Slavs. Painting by Sergei Ivanov, 1909 (Sevastopol Art Museum).

In the treaty of 907-911 we see only Scandinavian names, no others. And in the treaty of 944, three groups of people are distinguished. These are, first of all, the princes themselves, on whose behalf the agreement is concluded. With them are ambassadors and guests (merchants), who testify to the agreement. Among the ambassadors there are Finnish names, but no Slavic ones. And Slavic names appear among the merchants. And among the rulers, Igor’s relatives, Slavic names appear: Igor calls his son Svyatoslav, and a certain woman named Predslava is also known. Slavic names appear in the princely family.

It's the same in material culture. A so-called elite squad culture is being formed, in which Scandinavian, Slavic, and nomadic elements are mixed. A wonderful huge burial place, the Black Grave, in Chernigov. The warrior man and the youth were buried according to the Scandinavian rite. There are a number of Scandinavian items, for example, a cauldron with goat or lamb skins, a skull, weapons, and a horse at the feet according to Scandinavian custom. But, for example, a bag with a Hungarian ornament was discovered. The Hungarians at this time were nomads. Wonderful two Tur drinking horns, which are decorated with overlays also with nomadic motifs.

There is a mixing of cultures. Slavs, Finns, and nomads begin to join the squads. And by the middle of the 10th century, this common, no longer just Scandinavian, elite began to be called Russia. And the Russian princes are no longer quite Scandinavians. If at the initial stage, in Ladoga, Roots, Rus' was the Scandinavian rowers, then here it is the new military elite that rules the state. The territory subject to the Russian princes in Kyiv was called the Russian Land in treaties with the Greeks, and in modern terminology - the Old Russian State. Those who are under the authority of Russian princes are called Russians.

By the way, in Novgorod and Pskov, residents did not call themselves Russians for a very long time. They were Novgorodians or Slovenes. In the Novgorod chronicles we read that someone “goes to the Russian land” - that is, to the south, to Kyiv. At the beginning of the 10th century, the name Varangian appeared - from the Scandinavian word “var”, oath. The one who takes the oath is a mercenary. These are numerous detachments that come, are hired for service, go back, someone settles, trades... There is not a single case in the chronicle or in any other source that the princes were called Varangian. They are always Russian. Apparently, already in the 10th century and in the tradition that reached the chronicler, Rus' and the Varangians were fundamentally different.

The Scandinavians learned the Slavic language quite quickly, because they first of all needed to communicate with the local population, for example, to collect tribute. In the 10th century, the Scandinavian nobility were probably bilingual. We know about this from the same Constantine Porphyrogenitus. He describes in detail the route of the Ros to Constantinople. They sail from Kyiv, pass Vitichev, where the ships are equipped, and reach the Dnieper rapids. Now there are no Dnieper rapids, the Dnieper Hydroelectric Power Station has closed them. Konstantin describes these rapids in detail: how ships are unloaded, pulled through, etc. He names some rapids in Russian, others in Slavic and explains what this or that name means. All Russian names are undeniably Scandinavian. Konstantin most likely grew up as an informant, but he knows Slavic names well and speaks both languages. From the beginning of the 11th century, it is obvious that the Slavic language is becoming the only one.

Legendary Rurik

64. “Rurik’s arrival in Ladoga.” Painting by Viktor Vasnetsov, 1913.

65. “The calling of a prince is a meeting of the prince with his squad, elders and people of the Slavic city, 9th century.” Watercolor by Alexey Kivshenko, 1880.

66. “Rurik allows Askold and Dir to go on a campaign to Constantinople.” Radziwill Chronicle.

67. Rurik (17th century miniature from the “Tsar’s Titular Book”).

68. Monument to Rurik and the Prophetic Oleg in Staraya Ladoga (photo by Mikhail Friend, my-travels.club).

69. Rurik on the monument “Millennium of Russia” in Veliky Novgorod. Will you try to decipher the inscription on the shield?

How should we, in the end, thanks to the totality of a large number of sources (archaeological, linguistic, and written) relate to the legend of the calling of the Varangians? Of course, it should never be taken literally. This legend apparently originated in the 9th century and reflects a certain historical reality. The reality of the presence of the Scandinavians, their control over the trade route, the polity in Ladoga.

The motif of calling is generally very common in dynastic legends. Most likely, there were more than a dozen such “Ruriks”, and each one established their power here for some time. Probably, there really was a “row” (agreement) with the local nobility, which was important both for the squads of the Scandinavian “Rus” and for the local tribal formations. It is no coincidence that Novgorod later had a tradition of calling princes and concluding treaties with them.

The creation of the Tale of Bygone Years, the first official chronicle, was associated with the need to “put in order” the early history of Rus'. The chronicler sought to establish the unity of the princely family, calling on the Russian princes to unite. In addition, Vladimir, who at the end of the 10th century became a single ruler, needed to form a “public opinion” that Rurik, his ancestor, did not seize power, but achieved it in a fair way, according to the “row”. So, gradually, the “invitation of the Varangians” becomes the officially recognized beginning of the history of Rus', and Rurik becomes the founder of the Old Russian state and the dynasty of Russian rulers.

Sources and literature

Elena Aleksandrovna Melnikova is the author of over 250 scientific publications, including 7 monographs. We present here the main ones.

Melnikova E. A. Old Scandinavian geographical works: Texts, translation, commentary / Ed. V. L. Yanina. - M.: Nauka, 1986. - Series “Ancient sources on the history of the peoples of the USSR.”

Melnikova E. A. Sword and lyre. Anglo-Saxon society in history and epic. - M.: Mysl, 1987. - 208 p.: ill. - 50,000 copies.

Melnikova E. A. Image of the world: geographical representations in Western and Northern Europe. V-XIV centuries. - M., Janus-K, 1998. - 256 p. - ISBN 5-86218-270-5.

Ancient Rus' in the light of foreign sources / Ed. E. A. Melnikova. M.: Logos, 1999.

Melnikova E. A. Scandinavian runic inscriptions: new finds and interpretations. Texts, translation, commentary. - M.: Publishing company "Eastern Literature" RAS, 2001. - Series "Ancient sources on the history of Eastern Europe."

Melnikova E. A. Rurik, Sineus and Truvor in the Old Russian historiographical tradition. The most ancient states of Eastern Europe. – M.: Eastern literature, RAS, 2000.

Test tasks.

1. In ancient times in Rus', the inhabitants of the Scandinavian Peninsula were called

a) Vikings

b) Normans

c) Varangians

d) Scythians

2. How many centuries before Columbus did the Vikings discover America?

c) for 10

3. How were Eirik and Leif related?

a) were brothers

b) Eirik was the son of Leif

c) Eirik was Leif's father

d) Eirik was Leiv's grandfather

4. In order to get from Iceland to America through Greenland, the Vikings had to sail

a) first to the east and then to the north

b) first to the west and then to the south

c) first to the east, then to the south

d) first to the west, then to the north

5. The discovery of America by the Vikings is discussed in

a) “The Saga of the Icelanders”

b) “The Saga of the Greenlanders”

c) “The Saga of the Americans”

d) “The Saga of the Indians”

6. Fill in the gaps in the text.

The Vikings first settled the entire coast of the Scandinavian peninsula, then occupied the island of Iceland. Later they discovered and began to develop a huge island, which they called Greenland. A few years later, the son of Eirik the Red, whose name was Leif, managed to find a vast land, which the Vikings began to call Happy Vinland.

Thematic workshop.

Here are three excerpts from the Greenlanders' Saga. Put them in the correct order and answer the questions.

1. Eirik found the country he was looking for and approached the land near the glacier, which he called the Middle. He named the country he discovered Greenland (Green Country), because he believed that people would be more likely to want to go to a country if it had a good name.

2. One day a man disappeared, and then he came and brought a grapevine. And Leif named the country according to what was good in it: it was called the Grape Country or Vinland. This was around the year 1000. And after Leyv’s return, everyone began to call Leyv the Happy.

3. There lived a man named Torvald. He was the son of Asvald, son of the Bull Thorir. Thorvald and his son Eirik the Red left the Yard because of the murders they committed in the feud, and went to Iceland.

1. The cape in southern Africa has long been called the Cape of Storms. The Portuguese King João II renamed it the Cape of Good Hope. What do you think brings Leiva the Happy closer to King Juan II?

I think that both were at the Cape with good hope.

2. Who was Eirik the Red's relation to Bull Thorir?

Bull Thorir was the great-great-grandfather of Eirik the Red.

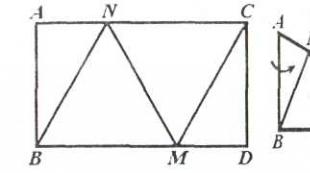

Cartographic workshop.

Trace the voyage route of the Vikings (Normans) on the map and name the geographical features through which it passed.

1. Norway.

2. Norwegian Sea.

3. Iceland.

4. Atlantic Ocean.

5. Greenland.

6. Baffin Island.

7. Lablador Peninsula.

8. Newfoundland Island.

For several centuries, before and after the year 1000, Western Europe was constantly attacked by "Vikings" - warriors who sailed on ships from Scandinavia. Therefore, the period is approximately from 800 to 1100. AD in the history of Northern Europe is called the “Viking Age”. Those who were attacked by the Vikings perceived their campaigns as purely predatory, but they also pursued other goals.

The Viking detachments were usually led by representatives of the ruling elite of Scandinavian society - kings and heads. Through robbery they acquired wealth, which they then divided among themselves and with their people. Victories in foreign countries brought them fame and position. Already in the early stages, the leaders also began to pursue political goals and take control of territories in the conquered countries. The chronicles say little about the significant increase in trade during the Viking Age, but archaeological finds indicate this. Cities flourished in Western Europe, and the first urban formations appeared in Scandinavia. The first city in Sweden was Birka, located on an island in Lake Mälaren, about 30 kilometers west of Stockholm. This city existed from the end of the 8th to the end of the 10th century; his successor in the Mälaren area was the city of Sigtuna, which today is an idyllic small town about 40 kilometers northwest of Stockholm.

The Viking Age is also characterized by the fact that many inhabitants of Scandinavia left their native places forever and settled in foreign countries, mainly as farmers. Many Scandinavians, primarily immigrants from Denmark, settled in the eastern part of England, undoubtedly with the support of the Scandinavian kings and rulers who ruled there. Large-scale Norse colonization took place in the Scottish islands; Norwegians also sailed the Atlantic Ocean to previously unknown, uninhabited places: the Faroe Islands, Iceland and Greenland (there were even attempts to settle in North America). During the 12th and 13th centuries, vivid accounts of the Viking Age were recorded in Iceland, not entirely reliable, but still irreplaceable as historical sources giving an idea of the pagan faith and way of thinking of the people of that time.

Contacts made during the Viking Age with the outside world radically changed Scandinavian society. Missionaries from Western Europe arrived in Scandinavia as early as the first century of the Viking Age. The most famous among them is Ansgarius, the "Scandinavian Apostle", who was sent by the Frankish king Louis the Pious to Birka around 830 and returned there again around 850. During the late Viking Age, an intensive process of Christianization began. The Danish, Norwegian and Swedish kings realized what power a Christian civilization and organization could give to their states, and carried out a change of religions. The process of Christianization was most difficult in Sweden, where at the end of the 11th century there was a fierce struggle between Christians and pagans.

The Viking Age in the East.

The Scandinavians not only traveled to the west, but also made long journeys to the east during the same centuries. For natural reasons, first of all, residents of places now belonging to Sweden rushed in this direction. Expeditions to the east and the influence of eastern countries left a special mark on the Viking Age in Sweden. Travel to the east was also undertaken when possible by ship - across the Baltic Sea, along the rivers of Eastern Europe to the Black and Caspian Seas, and along them to the great powers south of these seas: Christian Byzantium in the territory of modern Greece and Turkey and the Islamic Caliphate in eastern lands. Here, as well as to the west, ships sailed with oars and sails, but these ships were smaller than those used for voyages in a western direction. Their usual length was about 10 meters, and the team consisted of approximately 10 people. Larger ships were not needed for navigation in the Baltic Sea, and besides, they could not be used to travel along rivers.

Artist V. Vasnetsov "The Calling of the Varangians." 862 - invitation of the Varangians Rurik and his brothers Sineus and Truvor.

The fact that the campaigns to the east are less well known than the campaigns to the west is partly due to the fact that there are not many written sources about them. The script only came into use in Eastern Europe during the late Viking Age. However, from Byzantium and the Caliphate, which were the real great powers of the Viking Age from an economic and cultural point of view, contemporary travel accounts are known, as well as historical and geographical works telling about the peoples of Eastern Europe and describing trade travel and military campaigns from Eastern Europe to countries south of the Black and Caspian Seas. Sometimes among the characters in these images we can notice Scandinavians. As historical sources, these images are often more reliable and more complete than Western European chronicles written by monks and bearing the strong imprint of their Christian zeal and hatred of the pagans. A large number of Swedish rune stones are also known from the 11th century, almost all from the vicinity of Lake Mälaren; they were installed in memory of relatives who often traveled to the east. As for Eastern Europe, there is a wonderful Tale of Bygone Years dating back to the beginning of the 12th century. and telling about the ancient history of the Russian state - not always reliably, but always vividly and with an abundance of details, which greatly distinguishes it from Western European chronicles and gives it a charm comparable to the charm of the Icelandic sagas.

Ros - Rus - Ruotsi (Rhos - Rus - Ruotsi).

In 839, an ambassador from Emperor Theophilus from Constantinople (modern Istanbul) arrived to the Frankish king Louis the Pious, who was at that moment in Ingelheim on the Rhine. With the ambassador also came several people from the “Rus” people, who had traveled to Constantinople along such dangerous routes that they now wanted to return home through the kingdom of Louis. When the king asked more about these people, it turned out that they were their own. Louis knew the pagan Sueans well, since he himself had previously sent Ansgarius as a missionary to their trading city of Birka. The king began to suspect that the people who called themselves “ros” were actually spies, and decided to detain them until he found out their intentions. Such a story is contained in one Frankish chronicle. Unfortunately, it is unknown what happened to these people afterwards.

This story is important for the study of the Viking Age in Scandinavia. It and some other manuscripts from Byzantium and the Caliphate show more or less clearly that in the east in the 8th–9th centuries the Scandinavians were called “ros”/“rus” (rhos/rus). At the same time, this name was used to designate the Old Russian state, or, as it is often called, Kievan Rus (see map). The state grew during these centuries, and from it modern Russia, Belarus and Ukraine trace their origins.

The earliest history of this state is told in the Tale of Bygone Years, which was written down in its capital, Kyiv, shortly after the end of the Viking Age. In the entry for 862, one can read that the country was in turmoil, and it was decided to look for a ruler on the other side of the Baltic Sea. Ambassadors were sent to the Varangians (that is, Scandinavians), namely to those who were called “Rus”; Rurik and his two brothers were invited to rule the country. They came “with all Russia,” and Rurik settled in Novgorod. “And from these Varangians the Russian land got its name.” After Rurik’s death, rule passed to his relative Oleg, who conquered Kyiv and made this city the capital of his state, and after Oleg’s death, Rurik’s son Igor became prince.

The legend about the calling of the Varangians, contained in the Tale of Bygone Years, is a story about the origin of the Old Russian princely family, and as a historical source is very controversial. The name “Rus” has been tried to be explained in many ways, but now the most common opinion is that this name should be compared with the names from the Finnish and Estonian languages - Ruotsi / Rootsi, which today mean “Sweden”, and previously indicated peoples from Sweden or Scandinavia. This name, in turn, comes from an Old Norse word meaning "rowing", "rowing expedition", "members of a rowing expedition". It is obvious that the people who lived on the western coast of the Baltic Sea were famous for their sea trips with oars. There are no reliable sources about Rurik, and it is unknown how he and his “Rus” came to Eastern Europe - however, it is unlikely that this happened as simply and peacefully as the legend says. When the clan established itself as one of the ruling ones in Eastern Europe, soon the state itself and its inhabitants began to be called “Rus”. The fact that the family was of Scandinavian origin is indicated by the names of the ancient princes: Rurik is the Scandinavian Rörek, a common name in Sweden even in the late Middle Ages, Oleg - Helge, Igor - Ingvar, Olga (Igor's wife) - Helga.

To speak more definitely about the role of the Scandinavians in the early history of Eastern Europe, it is not enough just to study the few written sources; one must also take into account archaeological finds. They show a significant number of objects of Scandinavian origin, dating from the 9th–10th centuries, in the ancient part of Novgorod (Rurik settlement outside modern Novgorod), in Kiev and in many other places. We are talking about weapons, horse harness, as well as household items, and magical and religious amulets, for example, Thor's hammers, found at settlement sites, in burials and treasures.

It is obvious that in the region in question there were many Scandinavians who were involved not only in war and politics, but also in trade, crafts and agriculture - after all, the Scandinavians themselves came from agricultural societies, where urban culture, just like in Eastern Europe, began to develop only during these centuries. In many places the northerners left clear imprints of Scandinavian elements in culture - in clothing and the art of making jewelry, in weapons and religion. But it is also clear that the Scandinavians lived in societies whose structure was based on Eastern European culture. The central part of early cities usually consisted of a densely populated fortress - a detinets or a kremlin. Such fortified urban cores are not found in Scandinavia, but have long been characteristic of Eastern Europe. The construction method in the areas where the Scandinavians settled was mainly Eastern European, and most household items, such as household ceramics, also bore a local imprint. Foreign influence on culture came not only from Scandinavia, but also from countries in the east, south and southwest.

When Christianity was officially adopted in the Old Russian state in 988, Scandinavian features soon practically disappeared from its culture. Slavic and Christian Byzantine cultures became the main components in the culture of the state, and the language of the state and church became Slavic.

Caliphate - Serkland.

How and why did the Scandinavians participate in the developments that ultimately led to the formation of the Russian state? It was probably not only war and a thirst for adventure, but also to a large extent trade. The world's leading civilization during this period was the Caliphate, an Islamic state that extended east to Afghanistan and Uzbekistan in Central Asia; there, far to the east, were the largest silver mines of that time. Vast quantities of Islamic silver in the form of coins with Arabic inscriptions spread throughout Eastern Europe as far as the Baltic Sea and Scandinavia. The largest number of finds of silver objects was made in Gotland. From the territory of the Russian state and mainland Sweden, primarily from the area around Lake Mälaren, a number of luxury items are also known that indicate connections with the East that were of a more social nature - for example, details of clothing or feast items.When Islamic written sources mention "Rus" - by which, generally speaking, one can mean both the Scandinavians and other peoples from the Old Russian state, interest is shown primarily in their trading activity, although there are also stories about military campaigns, for example, against the city Berd in Azerbaijan in 943 or 944. In the world geography of Ibn Khordadbeh it is said that Russian merchants sold the skins of beavers and silver foxes, as well as swords. They came by ship to the lands of the Khazars, and, having paid tithes to their prince, set off further along the Caspian Sea. Often they carried their goods on camels all the way to Baghdad, the capital of the Caliphate. “They pretend to be Christians and pay the tax established for Christians.” Ibn Khordadbeh was the minister of security in one of the provinces along the caravan route to Baghdad, and he was well aware that these people were not Christians. The reason they called themselves Christians was purely economic - Christians paid lower taxes than pagans who worshiped many gods.

Besides fur, perhaps the most important commodity to come from the north were slaves. In the Caliphate, slaves were used as labor in most public sectors, and the Scandinavians, like other peoples, were able to obtain slaves during their military and predatory campaigns. Ibn Khordadbeh relates that slaves from the country of "Saklaba" (roughly meaning "Eastern Europe") served as translators for the Rus in Baghdad.

The flow of silver from the Caliphate dried up at the end of the 10th century. Perhaps the reason was the fact that silver production in the mines in the east decreased, perhaps it was influenced by the war and unrest that reigned in the steppes between Eastern Europe and the Caliphate. But another thing is also likely - that in the Caliphate they began to conduct experiments to reduce the silver content in the coin, and in connection with this, interest in coins in Eastern and Northern Europe was lost. The economy in these territories was not monetary; the value of a coin was calculated by its purity and weight. Silver coins and bars were cut into pieces and weighed on scales to obtain the price that a person was willing to pay for the goods. Silver of varying purity made this type of payment transaction difficult or virtually impossible. Therefore, the views of Northern and Eastern Europe turned towards Germany and England, where in the late period of the Viking Age a large number of full-weight silver coins were minted, which were distributed in Scandinavia, as well as in some areas of the Russian state.

However, back in the 11th century it happened that the Scandinavians reached the Caliphate, or Serkland, as they called this state. The most famous Swedish Viking expedition of this century was led by Ingvar, whom the Icelanders called Ingvar the Traveler. An Icelandic saga was written about him, however, it is very unreliable, but about 25 East Swedish rune stones tell about the people who accompanied Ingvar. All these stones indicate that the campaign ended in disaster. On one of the stones near Gripsholm in Södermanland you can read (according to I. Melnikova):

“Tola ordered this stone to be installed for her son Harald, Ingvar’s brother.

They left bravely

far beyond gold

and in the east

fed the eagles.

Died in the south

in Serkland."

So on many other runic stones, these proud lines about the campaign are written in verse. "To feed the eagles" is a poetic simile meaning "to kill one's enemies in battle." The meter used here is the old epic meter and is characterized by two stressed syllables in each line of poetry and the fact that the lines of poetry are linked in pairs by alliteration, that is, repeated initial consonants and alternating vowels.

Khazars and Volga Bulgars.

During the Viking Age, there were two important states in Eastern Europe dominated by Turkic peoples: the Khazar state in the steppes north of the Caspian and Black Seas, and the Volga Bulgar state in the Middle Volga. The Khazar Khaganate ceased to exist at the end of the 10th century, but the descendants of the Volga Bulgars live today in Tatarstan, a republic within the Russian Federation. Both of these states played an important role in the transmission of eastern influences to the Old Russian state and the countries of the Baltic region. A detailed analysis of Islamic coins showed that approximately 1/10 of them are imitation and were minted by the Khazars or, more often, by the Volga Bulgars.The Khazar Khaganate early adopted Judaism as the state religion, and the Volga Bulgar state officially adopted Islam in 922. In this regard, Ibn Fadlan visited the country, who wrote a story about his visit and meeting with merchants from Rus'. The most famous is his description of the burial of the Rus' head in a ship - a funeral custom characteristic of Scandinavia and also found in the Old Russian state. The funeral ceremony included the sacrifice of a slave girl, who was raped by the warriors of the troop before killing her and burning her along with her keeping. This is a story full of brutal details that would be hard to guess from archaeological excavations of Viking Age burials.

Varangians among the Greeks in Miklagard.

The Byzantine Empire, which in Eastern and Northern Europe was called Greece or the Greeks, according to the Scandinavian tradition was perceived as the main goal of campaigns to the east. In the Russian tradition, connections between Scandinavia and the Byzantine Empire also occupy a prominent place. The Tale of Bygone Years contains a detailed description of the path: “There was a path from the Varangians to the Greeks, and from the Greeks along the Dnieper, and in the upper reaches of the Dnieper - a portage to Lovot, and along Lovot you can enter Ilmen, a great lake; Volkhov flows from the same lake and flows into the Great Lake Nevo (Ladoga), and the mouth of that lake flows into the Varangian Sea (Baltic Sea)."The emphasis on the role of Byzantium is a simplification of reality. The Scandinavians came first of all to the Old Russian state and settled there. And trade with the Caliphate through the states of the Volga Bulgars and Khazars was to be of the greatest importance from an economic point of view for Eastern Europe and Scandinavia during the 9th-10th centuries.

However, during the Viking Age, and especially after the Christianization of the Old Russian state, the importance of connections with the Byzantine Empire increased. This is evidenced primarily by written sources. For unknown reasons, the number of finds of coins and other objects from Byzantium is relatively small in both Eastern and Northern Europe.

Around the end of the 10th century, the Emperor of Constantinople established a special Scandinavian detachment at his court - the Varangian Guard. Many believe that the beginning of this guard was laid by those Varangians whom the Kiev prince Vladimir sent to the emperor in connection with his adoption of Christianity in 988 and his marriage to the emperor’s daughter.

The word vringar originally meant oath-bound people, but in the late Viking Age it became a common name for the Scandinavians in the east. Waring in the Slavic language began to be called Varangian, in Greek - varangos, in Arabic - warank.

Constantinople, or Miklagard, the great city, as the Scandinavians called it, was incredibly attractive to them. The Icelandic sagas tell of many Norwegians and Icelanders who served in the Varangian Guard. One of them, Harald the Severe, became king of Norway upon his return home (1045-1066). Swedish rune stones of the 11th century more often speak of a stay in Greece than in the Old Russian state.

On the old path leading to the church at Ede in Uppland there is a large stone with runic inscriptions on both sides. In them, Ragnvald talks about how these runes were carved in memory of his mother Fastvi, but above all he is interested in talking about himself:

"These runes were ordered

flog Ragnvald.

He was in Greece

was the leader of a detachment of warriors."

Soldiers from the Varangian Guard guarded the palace in Constantinople and took part in military campaigns in Asia Minor, the Balkan Peninsula and Italy. The land of the Lombards, mentioned on several rune stones, refers to Italy, the southern regions of which were part of the Byzantine Empire. In the port suburb of Athens, Piraeus, there used to be a huge luxurious marble lion, which was transported to Venice in the 17th century. On this lion, one of the Varangians, while on holiday in Piraeus, carved a runic inscription of a serpentine shape, which was typical of Swedish rune stones of the 11th century. Unfortunately, even upon discovery, the inscription was so badly damaged that only individual words could be read.

Scandinavians in Gardarik during the late Viking Age.

At the end of the 10th century, as already mentioned, the flow of Islamic silver dried up, and instead of it, a flow of German and English coins poured into the east, into the Russian state. In 988, the Kiev prince and his people adopted quantities on Gotland, where they were also copied, and in mainland Sweden and Denmark. Several belts have even been discovered in Iceland. Perhaps they belonged to people who served the Russian princes.

Relations between the rulers of Scandinavia and the Old Russian state during the 11th-12th centuries were very lively. Two of the great princes of Kiev took wives in Sweden: Yaroslav the Wise (1019-1054, previously reigned in Novgorod from 1010 to 1019) married Ingegerd, daughter of Olav Shetkonung, and Mstislav (1125-1132, previously reigned in Novgorod from 1095 to 1125) - on Christina, daughter of King Inge the Old.

Novgorod - Holmgard and trade with the Sami and Gotlanders.

Eastern, Russian influence also reached the Sami in northern Scandinavia in the 11th-12th centuries. In many places in Swedish Lapland and Norrbotten there are places of sacrifice on the banks of lakes and rivers and near strangely shaped rocks; There are deer antlers, animal bones, arrowheads, and also tin. Many of these metal objects come from the Old Russian state, most likely from Novgorod - for example, the forging of Russian belts of the same kind that were found in the southern part of Sweden.

Novgorod, which the Scandinavians called Holmgard, acquired enormous importance over these centuries as a trading metropolis. The Gotlanders, who continued to play an important role in Baltic trade in the 11th-12th centuries, created a trading post in Novgorod. At the end of the 12th century, the Germans appeared in the Baltic, and gradually the main role in Baltic trade passed to the German Hanse.

End of the Viking Age.

On a simple casting mold for cheap ornaments, made of whetstone and found at Tiemans in Rum on Gotland, two Gotlanders at the end of the 11th century carved their names, Urmiga and Ulvat, and, in addition, the names of four distant countries. They make us understand that the world for the Scandinavians in the Viking Age had wide borders: Greece, Jerusalem, Iceland, Serkland.

It is impossible to name the exact date when this world shrank and the Viking Age ended. Gradually, during the 11th and 12th centuries, routes and connections changed their character, and in the 12th century, travel deep into the Old Russian state and to Constantinople and Jerusalem ceased. As the number of written sources in Sweden increased in the 13th century, campaigns to the east became just memories.

In the Elder Version of the Westgotalag, written in the first half of the 13th century, in the Chapter on Inheritance there is, among other things, the following provision regarding the one who is found abroad: He does not inherit from anyone while he sits in Greece. Did Westgoeths really still serve in the Varangian Guard, or did this paragraph remain from times long past?

The Gutasag, an account of the history of Gotland written in the 13th or early 14th century, states that the first churches on the island were consecrated by bishops on their way to or from the Holy Land. At that time, the route went east through Rus' and Greece to Jerusalem. When the saga was recorded, the pilgrims took a detour through Central or even Western Europe.

Translation: Anna Fomenkova.

Do you know that...

The Scandinavians who served in the Varangian Guard were probably Christians - or converted to Christianity while in Constantinople. Some of them made pilgrimages to the Holy Land and Jerusalem, called Yorsalir in the Scandinavian language. The rune stone from Brüby to Täby in Uppland was erected in memory of Øystein, who went to Jerusalem and died in Greece.Another runic inscription from Uppland, from Stacket in Kungsängen, tells of a determined and fearless woman: Ingerun, daughter of Hord, ordered runes to be carved in memory of herself. She goes east and to Jerusalem.

In 1999, the largest treasure of silver objects dating back to the Viking Age was found on Gotland. Its total weight is about 65 kilograms, of which 17 kilograms are Islamic silver coins (approximately 14,300).

The material uses pictures from the article.

games for girls

Viking Campaigns

Every Scandinavian from childhood dreamed of distant military campaigns, rich booty and the glory of a great leader. Many Vikings gathered fighting squads and went to foreign lands in search of gold and glory.The Vikings have always been considered excellent sailors and fearless warriors; they suddenly appeared on their fast ships, spreading fear and destruction everywhere. Most of the Vikings who took part in the campaigns were professional warriors.

The Vikings went on campaigns only by ship; they crossed seas and oceans, sailed along rivers deep into the continents. Thanks to their high-speed ships, which have unique maneuverability and are not afraid of the open sea and storms, the Vikings spread widely throughout the world. Their longships roamed the expanses from the shores of North America to the Caspian Sea, from the coasts of North Africa, to the ice of Greenland.

The Vikings mainly used the tactics of surprise attacks, but they often took part in field battles. The Vikings did not have cavalry; the dense formation was covered by scattered archers and dart throwers. Differently armed warriors alternated in the ranks. Spearmen with heavy northern spears, shackled along the shaft so as not to cut down the tree, walked in ranks with swordsmen and warriors armed with axes or axes. The spearman moved his spear with both hands, and the swordsman covered both him and himself with his shield, waiting for the moment to strike.

Berserkers

Berserkers brought particular fear to the enemy. It is believed that these warriors ate fly agarics and drank a special potion, which caused a fit of frantic rage, during which they acquired incredible strength. When berserkers were overcome by such madness, they became insensitive to pain and wounds and believed that neither sword nor fire could harm them. Therefore, most often they fought without armor.

Berserker translated means “bear jacket”; according to legend, these warriors were possessed by the spirit of a ferocious bear, which gave them its monstrous strength. Before the battle, they gnashed their teeth and bit the edges of their shields. The berserkers fought like rabid animals, rushing into the thick of the battle, destroying everything around them.

After the battle, the spoils were carried to a pole in the center of the battlefield and divided among the warriors according to their merits. Viking attacks did not always end successfully. They themselves were often defeated by regular troops.