From what family of non-krasians? N. A. Nekrasov. Nekrasov, Nikolai Alekseevich

“Nekrasov retains immortality, which he well deserves.” F.M. Dostoevsky “Nekrasov’s personality is still a stumbling block for everyone who is in the habit of judging with stereotyped ideas.” A.M.Skobichevsky

ON THE. Nekrasov

On December 10 (November 28, old style), Nikolai Alekseevich Nekrasov was born - a brilliant publisher, writer-publicist, close to revolutionary democratic circles, permanent editor and publisher of the Sovremennik magazine (1847-1866).

Before Nekrasov, in the Russian literary tradition there was a view of poetry as a way of expressing feelings, and prose as a way of expressing thoughts. The 1850-60s are the time of the next “great turning point” in the history of Russia. Society did not just demand economic, social and political changes. A great emotional explosion was brewing, an era of revaluation of values, which ultimately resulted in fruitless flirtations of the intelligentsia with the popular element, fanning the revolutionary fire and a complete departure from the traditions of romanticism in Russian literature. Responding to the demands of his difficult times, Nekrasov decided to prepare a kind of “salad” of folk poetry and accusatory journalistic prose, which was very much to the taste of his contemporaries. The main theme of such “adapted” poetry is man as a product of a certain social environment, and sadness about this man (according to Nekrasov) is the main task of the best citizens of contemporary Russian society.

The journalistic essays of the “sorrowful man” Nekrasov, dressed in an emotional and lyrical package, have long been a model of civil poetry for democratic writers of the second half of the 19th and early 20th centuries. And although the sensible minority of Russian society did not at all consider Mr. Nekrasov’s rhymed feuilletons and proclamations to be high poetry, already during the author’s lifetime some of them were included in school curricula, and Nekrasov himself acquired the status of a “truly people’s poet.” True, only among the “repentant” noble-raznochin intelligentsia in every way. The people themselves did not even suspect the existence of the poet Nekrasov (as well as Pushkin and Lermontov).

Publisher of one of the most widely read magazines, successful businessman from literature, N.A. Nekrasov fit perfectly into his difficult era. For many years he managed to manipulate the literary tastes of his contemporaries, sensitively responding to all the demands of the political, economic, literary market of the second half of the 19th century. Nekrasov’s “Contemporary” became the focus and center of attraction for a wide variety of literary and political movements: from the very moderate liberalism of Turgenev and Tolstoy to the democratic revolutionaries (Dobrolyubov and Chernyshevsky).

In his poetic stylizations, Nekrasov raised the most painful, most pressing problems of pre-reform and post-reform Russia of the 19th century. Many of his plot sketches were subsequently reflected in the works of recognized classics of Russian literature. Thus, the entire philosophy and even the “poetics” of suffering in F.M. Dostoevsky's ideas were largely formed under the direct and strong influence of Nekrasov.

It is to Nekrasov that we owe many “catchphrases” and aphorisms that have forever entered our everyday speech. (“Sow what is reasonable, good, eternal”, “The happy are deaf to good”, “There have been worse times, but there have been no mean ones”, etc.)

Family and ancestors

ON THE. Nekrasov twice seriously tried to inform the public of the main milestones of his interesting biography, but each time he tried to do this at the most critical moments for himself. In 1855, the writer believed that he was terminally ill, and was not going to write the story of his life because he had recovered. And twenty years later, in 1877, being truly terminally ill, he simply did not have time.

However, it is unlikely that descendants would be able to glean any reliable information or facts from these author’s stories. Nekrasov needed an autobiography solely for self-confession, aimed at teaching and edifying literary descendants.

“It occurred to me to write for the press, but not during my lifetime, my biography, that is, something like confessions or notes about my life - in a fairly extensive size. Tell me: isn’t this too - so to speak - proud?” - he asked in one of his letters to I.S. Turgenev, on which he then tested almost everything. And Turgenev replied:

“I fully approve of your intention to write your biography; your life is precisely one of those that, putting all pride aside, must be told - because it represents a lot of things that more than one Russian soul will deeply respond to.”

Neither an autobiography nor a recording of N.A. Nekrasov’s literary memoirs ever took place. Therefore, everything that we know today about the early years of the “sorrowful man of the Russian land” was gleaned by biographers exclusively from the literary works of Nekrasov and the memories of people close to him.

As evidenced by several options for the beginning of Nekrasov’s “autobiography,” Nikolai Alekseevich himself could not really decide on the year, day, or place of his birth:

“I was born in 1822 in the Yaroslavl province. My father, the old adjutant of Prince Wittgenstein, was a retired captain...”

“I was born in 1821 on November 22 in the Podolsk province in the Vinnitsa district in some Jewish town, where my father was then stationed with his regiment...”

In fact, N.A. Nekrasov was born on November 28 (December 10), 1821 in the Ukrainian town of Nemirov. One of the modern researchers also believes that his place of birth was the village of Sinki in the current Kirovograd region.

No one has written the history of the Nekrasov family either. The noble family of the Nekrasovs was quite ancient and purely Great Russian, but due to their lack of documents, it was not included in that part of the genealogical book of the nobles of the Yaroslavl province, where the pillar nobility was placed, and the official count goes in the second part from 1810 - according to the first officer rank of Alexei Sergeevich Nekrasov (father of the future poet). The coat of arms of the Nekrasovs, approved by Emperor Nicholas II in April 1916, was also recently found.

Once upon a time the family was very rich, but starting from their great-grandfather, the Nekrasovs’ affairs went from bad to worse, thanks to their addiction to card games. Alexey Sergeevich, telling his glorious pedigree to his sons, summarized: “Our ancestors were rich. Your great-great-grandfather lost seven thousand souls, your great-grandfather - two, your grandfather (my father) - one, I - nothing, because there was nothing to lose, but I also like to play cards.”

His son Nikolai Alekseevich was the first to change his fate. No, he did not curb his destructive passion for cards, he did not stop playing, but he stopped losing. All his ancestors lost - he was the only one who won back. And he played a lot. The count was, if not millions, then hundreds of thousands. His card partners included large landowners, important government dignitaries, and very rich people of Russia. According to Nekrasov himself, the future Minister of Finance Abaza alone lost about a million francs to the poet (at the then exchange rate - half a million Russian rubles).

However, success and financial well-being did not come to N.A. Nekrasov right away. If we talk about his childhood and youth, they were indeed full of deprivation and humiliation, which subsequently affected the character and worldview of the writer.

N.A. Nekrasov spent his childhood on the Yaroslavl estate of his father Greshnevo. The relationship between the parents of the future poet left much to be desired.

In an unknown wilderness, in a semi-wild village, I grew up among violent savages, And fate, by great mercy, gave me the leadership of hounds.

By “dogkeeper” we should here understand the father - a man of unbridled passions, a limited domestic tyrant and tyrant. He devoted his entire life to litigation with relatives on estate matters, and when he won the main case for the ownership of a thousand serf souls, the Manifesto of 1861 was published. The old man could not survive the “liberation” and died. Before this, Nekrasov’s parents had only about forty serfs and thirteen children. What kind of family idyll could we be talking about in such conditions?

The mature Nekrasov subsequently abandoned many of his incriminating characteristics against his serf-owning parent. The poet admitted that his father was no worse and no better than other people in his circle. Yes, he loved hunting, kept dogs, a whole staff of hounds, and actively involved his older sons in hunting activities. But the traditional autumn hunt for the small nobleman was not just fun. Given the general limitation of funds, hunting prey is a serious help in the economy. It made it possible to feed a large family and servants. Young Nekrasov understood this perfectly.

By the writer’s own admission, his early works (“Motherland”) were influenced by youthful maximalism and a tribute to the notorious “Oedipus complex” - filial jealousy, resentment against a parent for betraying his beloved mother.

Nekrasov carried the bright image of his mother, as the only positive memory of his childhood, throughout his life, embodying it in his poetry. To this day, Nekrasov’s biographers do not know anything real about the poet’s mother. She remains one of the most mysterious images associated with Russian literature. There were no images (if there were any), no objects, no written documentary materials. From the words of Nekrasov himself, it is known that Elena Andreevna was the daughter of a rich Little Russian landowner, a well-educated, beautiful woman, who for some unknown reason married a poor, unremarkable officer and went with him to the Yaroslavl province. Elena Andreevna died quite young - in 1841, when the future poet was not even 20 years old. Immediately after the death of his wife, the father brought his serf mistress into the house as a mistress. “You saved the living soul in me,” the son will write in poetry about his mother. Her romantic image will be the main leitmotif throughout N.A.’s subsequent work. Nekrasova.

At the age of 11, Nikolai and his older brother Andrei went to study at a gymnasium in Yaroslavl. The brothers studied poorly, reaching only 5th grade without being certified in a number of subjects. According to the memoirs of A.Ya. Panaeva, Nekrasov said that the “in-law” high school students lived in the city, in a rented apartment under the supervision of only one drinking “guy” from their father’s serfs. The Nekrasovs were left to their own devices, walked the streets all day long, played billiards and did not bother themselves too much with reading books or going to the gymnasium:

At the age of fifteen, I was fully educated, as my father’s ideal demanded: The hand is steady, the eye is true, the spirit is tested, But I knew very little about reading and writing.

Nevertheless, by the age of 13-14, Nikolai knew “literate”, and quite well. For a year and a half, Nekrasov’s father held the position of police officer - district police chief. The teenager acted as his secretary and traveled with his parent, observing with his own eyes the criminal life of the county in all its unsightly light.

So, as we see, there was no trace of anything similar to the excellent home education of Pushkin or Lermontov behind the shoulders of the future poet Nekrasov. On the contrary, he could be considered a poorly educated person. Until the end of his life, Nekrasov never learned a single foreign language; The young man's reading experience also left much to be desired. And although Nikolai began writing poetry at the age of six or seven, by the age of fifteen his poetic creations were no different from the “test of the pen” of most of the noble minors of his circle. But the young man had excellent hunting skills, rode excellently, shot accurately, was physically strong and resilient.

It is not surprising that my father insisted on a military career - several generations of Nekrasov nobles served the Tsar and the Fatherland quite successfully. But the son, who had never been known for his love of science, suddenly wanted to go to university. There was a serious disagreement in the family.

“Mother wanted,” Chernyshevsky recalled from Nekrasov’s words, “for him to be an educated person, and told him that he should go to university, because education is acquired at a university, and not in special schools. But my father did not want to hear about it: he agreed to let Nekrasov go no other way than to enter the cadet corps. It was useless to argue, his mother fell silent... But he was traveling with the intention of entering not the cadet corps, but the university...”

Young Nekrasov went to the capital in order to deceive his father, but he himself was deceived. Lacking sufficient preparation, he failed the university exams and flatly refused to enter the cadet corps. The angry Alexey Sergeevich left his sixteen-year-old son without any means of subsistence, leaving him to arrange his own destiny.

Literary tramp

It is safe to say that not a single Russian writer had anything even close to the life and everyday experience that young Nekrasov went through in his first years in St. Petersburg. He later called one of his stories (an excerpt from the novel) “Petersburg Corners.” He could only have written, on the basis of personal memories, some kind of “Petersburg Bottom”, which Gorky himself had not visited.

In the 1839-1840s, Nekrasov tried to enter Russian literature as a lyric poet. Several of his poems were published in magazines (“Son of the Fatherland”, “Library for Reading”). He also had a conversation with V.A. Zhukovsky, the Tsarevich’s tutor and mentor to all young poets. Zhukovsky advised the young talent to publish his poems without a signature, because then he would be ashamed.

In 1840, Nekrasov published a poetry collection “Dreams and Sounds”, signing the initials “N.N.” The book was not a success, and the reviews from critics (including V.G. Belinsky) were simply devastating. It ended with the author himself buying up the entire circulation and destroying it.

Nevertheless, the then still very young Nekrasov was not disappointed in his chosen path. He did not take the pose of an offended genius, nor did he descend into vulgar drunkenness and fruitless regrets. On the contrary, the young poet showed the greatest sobriety of mind, complete self-criticism that never betrayed him in the future.

Nekrasov later recalled:

“I stopped writing serious poetry and began to write selfishly,” in other words - to earn money, for money, sometimes just so as not to die of hunger.

With “serious poetry,” as with the university, the matter ended in failure. After the first failure, Nekrasov made repeated attempts to prepare and take the entrance exams again, but received only units. For some time he was listed as a volunteer student at the Faculty of Philosophy. I listened to lectures for free, since my father obtained a certificate from the Yaroslavl leader of the nobility about his “insufficient condition.”

Nekrasov’s financial situation during this period can be characterized in one word – “hunger.” He wandered around St. Petersburg almost homeless, always hungry, poorly dressed. According to later acquaintances, in those years even the poor felt sorry for Nekrasov. One day he spent the night in a shelter, where he wrote a certificate to a poor old woman and received 15 kopecks from her. On Sennaya Square, he earned extra money by writing letters and petitions to illiterate peasants. Actress A.I. Schubert recalled that she and her mother nicknamed Nekrasov “unfortunate” and fed him, like a stray dog, with the remains of their lunch.

At the same time, Nekrasov was a man of passionate, proud and independent character. This was precisely confirmed by the whole story of the break with his father, and his entire subsequent fate. Initially, pride and independence manifested themselves precisely in their relationship with their father. Nekrasov never complained about anything and never asked for anything from either his father or his brothers. In this regard, he owes his fate only to himself - both in a bad and in a good sense. In St. Petersburg, his pride and dignity were constantly tested, he suffered insults and humiliation. It was then, apparently, on one of the bitterest days, that the poet promised himself to fulfill one oath. It must be said that oaths were in fashion at that time: Herzen and Ogarev swore on Vorobyovy Gory, Turgenev swore an “Annibal oath” to himself, and L. Tolstoy swore in his diaries. But neither Turgenev, nor Tolstoy, much less Ogarev and Herzen, were ever threatened with starvation or cold death. Nekrasov, like Scarlett O'Hara, the heroine of M. Mitchell's novel, vowed to himself only one thing: not to die in the attic.

Perhaps only Dostoevsky fully understood the ultimate meaning, the unconditional significance of such an oath of Nekrasov and the almost demonic rigor of its fulfillment:

“A million - that’s Nekrasov’s demon! Well, did he love gold, luxury, pleasures so much and, in order to have them, indulged in “practicalities”? No, rather it was a demon of a different nature, it was the darkest and most humiliating demon. It was a demon of pride, the thirst for self-sufficiency, the need to protect yourself from people with a solid wall and independently, calmly look at their threats. I think this demon latched onto the heart of a child, a child of fifteen years old, who found himself on the St. Petersburg pavement, almost running away from his father... It was a thirst for gloomy, gloomy, isolated self-sufficiency, so as not to depend on anyone. I think I'm not mistaken, I remember something from my very first acquaintance with him. At least that’s how it seemed to me all my life. But this demon was still a low demon...”

Lucky case

Almost all of Nekrasov’s biographers note that no matter how the fate of the “great sad man of the Russian land” turned out, sooner or later he would have been able to get out of the St. Petersburg bottom. At any cost, he would have built his life as he saw fit, and would have been able to achieve success, if not in literature, then in any other field. One way or another, Nekrasov’s “low demon” would be satisfied.

I.I. Panaev

However, it is no secret to anyone that to firmly enter the literary environment and embody all his talents - as a writer, journalist, publicist and publisher - N.A. Nekrasov was helped by that “happy occasion” that happens once in a lifetime. Namely, a fateful meeting with the Panayev family.

Ivan Ivanovich Panaev, Derzhavin’s grandnephew, a rich darling of fortune, a dandy and rake known throughout St. Petersburg, also dabbled in literature. In his living room there was one of the most famous literary salons in Russia at that time. Here, at times, one could simultaneously meet the entire flower of Russian literature: Turgenev, L. Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Goncharov, Belinsky, Saltykov-Shchedrin, Ostrovsky, Pisemsky and many, many others. The hostess of the hospitable house of the Panayevs was Avdotya Yakovlevna (nee Bryanskaya), the daughter of a famous actor of the imperial theaters. Despite an extremely superficial education and blatant illiteracy (until the end of her life she made spelling errors in the simplest words), Avdotya Yakovlevna became famous as one of the very first Russian writers, albeit under the male pseudonym N. Stanitsky.

Her husband Ivan Panaev not only wrote stories, novels and stories, but also loved to act as a patron of the arts and benefactor for poor writers. So, in the fall of 1842, rumors spread throughout St. Petersburg about another “good deed” by Panaev. Having learned that his colleague in the literary workshop was in poverty, Panaev came to Nekrasov in his smart carriage, fed him and lent him money. Saved, in general, from starvation.

In fact, Nekrasov did not even think about dying. During that period, he supplemented himself with occasional literary work: he wrote custom poems, vulgar vaudeville acts for theaters, made posters, and even gave lessons. Four years of wandering life only strengthened him. True to his oath, he waited for the moment when the door to fame and money would open before him.

This door turned out to be the door to the Panayevs’ apartment.

Nekrasov and Panaev.

Caricature by N.A. Stepanova, “Illustrated Almanac”, 1848

At first, writers only invited the young poet to their evenings, and when he left, they kindly laughed at his simple poems, poor clothes, and uncertain manners. Sometimes they simply felt sorry as human beings, just as they feel sorry for homeless animals and sick children. However, Nekrasov, who was never overly shy, with surprising speed took his place in the literary circle of young St. Petersburg writers united around V.G. Belinsky. Belinsky, as if repenting for his review of “Dreams and Sounds,” took literary patronage over Nekrasov, introduced him to the editorial office of “Otechestvennye Zapiski,” and allowed him to write serious critical articles. They also began publishing an adventure novel by a young author, “The Life and Adventures of Tikhon Trostnikov.”

The Panaevs also developed a feeling of sincere friendship for the talkative, witty Nekrasov. The young poet, when he wanted, could be an interesting conversationalist and knew how to win people over. Of course, Nekrasov immediately fell in love with the beautiful Avdotya Yakovlevna. The hostess behaved quite freely with the guests, but was equally sweet and even with everyone. If her husband’s love affairs often became known to the whole world, then Mrs. Panaeva tried to maintain external decency. Nekrasov, despite his youth, had another remarkable quality - patience.

In 1844, Panaev rented a new spacious apartment on the Fontanka. He made another broad gesture - he invited family friend Nekrasov to leave his miserable corner with bedbugs and move to live with him on Fontanka. Nekrasov occupied two small cozy rooms in Ivan Ivanovich’s house. Absolutely free. In addition, he received as a gift from the Panayevs a silk muffler, a tailcoat and everything that a decent socialite should have.

"Contemporary"

Meanwhile, there was a serious ideological division in society. Westerners rang the “Bell”, calling to be equal to the liberal West. Slavophiles called to the roots, plunging headlong into the still completely unexplored historical past. The guards wanted to leave everything as it was. In St. Petersburg, writers were grouped “by interests” around magazines. Belinsky’s circle was then warmed up by A. Kraevsky in Otechestvennye zapiski. But under conditions of strict government censorship, the not-too-brave Kraevsky devoted most of the magazine space to proven and safe historical novels. The youth were cramped within these narrow confines. In Belinsky's circle, conversations began about opening a new, their own magazine. However, fellow writers were not distinguished by either their practical acumen or their ability to get things done. There were voices that it would be possible to hire a smart manager, but to what extent would he share their beliefs?

And then in their midst there was such a person - Nikolai Alekseevich Nekrasov. It turned out that he knows something about publishing. Back in 1843-46, he published the almanacs “Articles in Poems”, “Physiology of St. Petersburg”, “First of April”, “Petersburg Collection”. In the latter, by the way, “Poor People” by F.M. were first published. Dostoevsky.

Nekrasov himself later recalled:

“I was the only practical person among the idealists, and when we started the magazine, the idealists told me this directly and entrusted me with a kind of mission to create a magazine.”

Meanwhile, in addition to desire and skill, to create a magazine you also need the necessary funds. Neither Belinsky nor any of the writers, except Ivan Panaev, had enough money at that time.

Nekrasov said that it would be cheaper to buy or lease an existing magazine than to create something new. I found such a magazine very quickly.

Sovremennik, as you know, was founded by Pushkin in 1836. The poet managed to release only four issues. After Pushkin’s death, Sovremennik passed to his friend, poet and professor at St. Petersburg University P.A. Pletnev.

Pletnev had neither the time nor the energy to engage in publishing work. The magazine eked out a miserable existence, did not bring in any income, and Pletnev did not abandon it only out of loyalty to the memory of his deceased friend. He quickly agreed to lease Sovremennik with subsequent sale in installments.

Nekrasov needed 50 thousand rubles for the initial payment, bribes to censors, fees and first expenses. Panaev volunteered to give 25 thousand. It was decided to ask for the remaining half from Panaev’s old friend, the richest landowner G.M. Tolstoy, who held very radical views, was friends with Bakunin, Proudhon, and was friends with Marx and Engels.

In 1846, the Panaev couple, together with Nekrasov, went to Tolstoy in Kazan, where one of the estates of the supposed philanthropist was located. From a business perspective, the trip turned out to be pointless. Tolstoy at first willingly agreed to give money for the magazine, but then refused, and Nekrasov had to collect the remaining amount bit by bit: Herzen’s wife gave five thousand, the tea merchant V. Botkin donated about ten thousand, Avdotya Yakovlevna Panaeva allocated something from her personal capital. Nekrasov himself obtained the rest with the help of loans.

Nevertheless, on this long and tiring trip to Kazan, a spiritual rapprochement between Nikolai Alekseevich and Panaeva took place. Nekrasov used a win-win trump card - he told Avdotya Yakovlevna in every detail about his unhappy childhood and poverty-stricken years in St. Petersburg. Panaeva took pity on the unfortunate unfortunate man, and such a woman was only one step from pity to love.

Already on January 1, 1847, the first book of the new, already Nekrasov’s Sovremennik was brought from the printing house. The first issue immediately attracted the attention of readers. Today it seems strange that things that had long since become textbooks were once published for the first time, and almost no one knew the authors. The first issue of the magazine published “Khor and Kalinich” by I.S. Turgenev, “A Novel in Nine Letters” by F.M. Dostoevsky, “Troika” by N.A. Nekrasov, poems by Ogarev and Fet, and the story “Relatives” by I. Panaev. The critical section was decorated with three reviews by Belinsky and his famous article “A Look at Russian Literature of 1846.”

The publication of the first issue was also crowned by a large gala dinner, which opened, as Pushkin would say, “a long row of dinners” - a long-standing tradition: this is how the release of each magazine book was celebrated. Subsequently, Nekrasov's rich drunken feasts came not so much from lordly hospitality, but from sober political and psychological calculations. The success of the magazine's literary affairs was ensured not only by written tables, but also by feast tables. Nekrasov knew very well that “when drunk” Russian affairs are accomplished more successfully. Another agreement over a glass may turn out to be stronger and more reliable than an impeccable legal deal.

Publisher Nekrasov

From the very beginning of his work at Sovremennik, Nekrasov proved himself to be a brilliant businessman and organizer. In the first year, the magazine's circulation increased from two hundred copies to four thousand (!). Nekrasov was one of the first to realize the importance of advertising for increasing subscriptions and increasing the financial well-being of the magazine. He cared little about the ethical standards of publishing that were accepted at that time. There were no clearly defined laws. And what is not prohibited is permitted. Nekrasov ordered the printing of a huge number of color Sovremennik advertising posters, which were posted all over St. Petersburg and sent to other cities. He advertised subscriptions to the magazine in all St. Petersburg and Moscow newspapers.

In the 1840s and 50s, translated novels were especially popular. Often the same novel was published in several Russian magazines. To get them, you didn’t have to buy publishing rights. It was enough to buy a cheap brochure and print it in parts, without waiting for the entire novel to be translated. It’s even easier to get several issues of foreign newspapers, where modern fiction was published in the “basements.” Nekrasov kept a whole staff of travelers who, when visiting Europe, brought newspapers from there, and sometimes stole fresh proofs directly from the desks in the editorial offices. Sometimes typesetters or copyists (typists) were bribed to copy out the authors' scribbles. It often happened that a novel in Russian translation was published in Sovremennik faster than it was published entirely in its native language.

Numerous book supplements also helped to increase the magazine's circulation - for subscribers at a reduced price. To attract a female audience, a paid application was released with beautiful color pictures of the latest Parisian fashions and detailed explanations by Avdotya Yakovlevna on this issue. Panayeva’s materials were sent from Paris by her friend, Maria Lvovna Ogareva.

In the very first year, the talented manager Nekrasov ensured that the number of Sovremennik subscribers reached 2,000 people. Next year – 3100.

Needless to say, none of the fellow writers around him possessed either such practical acumen or (most importantly) the desire to deal with financial affairs and “promote” the magazine. Belinsky, admiring the extraordinary abilities of his recent mentee, did not even advise any of his friends to meddle in the business affairs of the publishing house: “You and I have nothing to teach Nekrasov; Well, what do we know!..”

There is nothing surprising in the fact that the efficient publisher very quickly removed his co-owner Panaev from any business at Sovremennik. At first, Nekrasov tried to divert his companion’s attention to writing, and when he realized that Ivan Ivanovich was not very capable of this, he simply wrote him off, both in business and personal terms.

“You and I are stupid people...”

Some contemporaries, and subsequently biographers of N.A. Nekrasov, more than once spoke about the mental imbalance and even ill health of Nikolai Alekseevich. He gave the impression of a man who had sold his soul to the devil. It was as if two different entities existed in his bodily shell: a prudent businessman who knows the value of everything in the world, a born organizer, a successful gambler and at the same time a depressed melancholic, sentimental, sensitive to the suffering of others, a very conscientious and demanding person. At times he could work tirelessly, single-handedly carry the entire burden of publishing, editorial, and financial affairs, showing extraordinary business activity, and at times he fell into impotent apathy and moped for weeks alone with himself, idle, without leaving the house. During such periods, Nekrasov was obsessed with thoughts of suicide, held a loaded pistol in his hands for a long time, looked for a strong hook on the ceiling, or got involved in dueling disputes with the most dangerous rules. Of course, the character, worldview, and attitude towards the world around the mature Nekrasov were affected by years of deprivation, humiliation, and struggle for his own existence. In the earliest period of his life, when the generally prosperous young nobleman had to endure several serious disasters, Nekrasov may have consciously abandoned his real self. Instinctively, he still felt that he was created for something else, but the “low demon” conquered more and more space for himself every year, and the synthesis of folk stylizations and social problems led the poet further and further away from his true purpose.

There is nothing surprising. Reading, and even more so composing such “poems” as “I’m Driving Down a Dark Street at Night” or “Reflections at the Front Entrance”, you will involuntarily fall into depression, develop mental illness, and become disgusted with yourself...

The substitution of concepts not only in literature, but also in life played a fatal, irreversible role in the personal fate of the poet Nekrasov.

1848 turned out to be the most unlucky year for Sovremennik. Belinsky died. A wave of revolutions swept across Europe. Censorship was rampant in Russia, prohibiting everything from moderately liberal statements by domestic authors to translations of foreign literature, especially French. Due to censorship terror, the next issue of Sovremennik was under threat. Neither bribes, nor lavish dinners, nor deliberate losses at cards to the “right people” could radically change the situation. If one bribed official allowed something, then another immediately prohibited it.

AND I. Panaeva

But the inventive Nekrasov found a way out of this vicious circle. To fill the pages of the magazine, he invites Avdotya Panayeva to urgently write an exciting, adventure and absolutely apolitical novel with a sequel. So that it does not look like “women’s handicraft,” Nekrasov becomes a co-author of his beautiful lady, who initially wrote under the male pseudonym N. Stanitsky. The novels “Three Countries of the World” (1849) and “Dead Lake” (1851) are the product of joint creativity, which allowed Sovremennik as a commercial enterprise to stay afloat during the years of pre-reform strengthening of the regime, which historians later called the “dark seven years” (1848-1855) .

Co-authorship brought Panaeva and Nekrasov so close that Avdotya Yakovlevna finally put an end to her imaginary marriage. In 1848, she became pregnant by Nekrasov, then they had a child desired by both parents, but he died a few weeks later. Nekrasov was very upset by this loss, and the unfortunate mother seemed petrified with grief.

In 1855, Nekrasov and Panaev buried their second, perhaps even more desired and expected son. This almost became the reason for the final break in relations, but Nekrasov became seriously ill, and Avdotya Yakovlevna could not leave him.

It just so happened that the fruit of the great love of two far from ordinary people remained only two commercial novels and truly lyrical poems, which were included in literature under the name “Panaevsky cycle”.

The true love story of Nekrasov and Panaeva, like the love lyrics of the “sorrowful” poet, the poet-citizen, destroyed all hitherto familiar ideas about the relationship between a man and a woman and their reflection in Russian literature.

For fifteen years, the Panaevs and Nekrasovs lived together, practically in the same apartment. Ivan Ivanovich did not interfere in any way with the relationship of his legal wife with “family friend” Nekrasov. But the relationship between Nikolai Alekseevich and Avdotya Yakovlevna was never smooth and cloudless. The lovers either wrote novels together, then ran away from each other in different cities and countries of Europe, then parted forever, then met again in the Panayevs’ St. Petersburg apartment, so that after some time they could run away and look for a new meeting.

Such relationships can be characterized by the proverb “together it’s crowded, but apart it’s boring.”

In the memoirs of contemporaries who observed Nekrasov and Panaeva at different periods of their lives, judgments are often found that these “stupid people” could never form a normal married couple. Nekrasov by nature was a fighter, hunter, and adventurer. He was not attracted by quiet family joys. During “quiet periods” he fell into depression, which at its climax often led to thoughts of suicide. Avdotya Yakovlevna was simply forced to take active actions (run away, sneak away, threaten to break up, make her suffer) in order to bring her loved one back to life. In Panaeva, Nekrasov - willingly or unwillingly - found the main nerve that for many years held the entire nervous basis of his creativity, his worldview and almost his very existence - suffering. The suffering that he received from her in full and which he fully endowed with her.

A tragic, perhaps defining imprint on their relationship was the suffering due to failed motherhood and fatherhood.

Modern researcher N. Skatov in his monograph on Nekrasov attaches decisive importance to this fact. He believes that only happy fatherhood could perhaps lead Nekrasov out of his spiritual impasse and establish normal family relationships. It is no coincidence that Nekrasov wrote so much about children and for children. In addition, the image of his beloved woman for him was always inextricably linked with the image of his mother.

For many years, Panaeva divided her failed maternal feelings between Nekrasov and her “unfortunate”, degraded husband, forcing the entire capital’s elite to practice barbs about this unusual “triple alliance.”

In Nekrasov's poems, the feeling of love appears in all its complexity, inconsistency, unpredictability and at the same time - everyday life. Nekrasov even poeticized the “prose of love” with its quarrels, disagreements, conflicts, separation, reconciliation...

You and I are stupid people: Any minute, the flash is ready! Relief from an agitated chest, An unreasonable, harsh word. Speak when you are angry, Everything that excites and torments your soul! Let us, my friend, be openly angry: The world is easier, and sooner it will get boring. If prose in love is inevitable, then let’s take a share of happiness from it: After a quarrel, the return of love and participation is so complete, so tender... 1851

For the first time, not one, but two characters are revealed in his intimate lyrics. It’s as if he is “playing” not only for himself, but also for his chosen one. Intellectual lyrics replace love ones. Before us is the love of two people busy with business. Their interests, as often happens in life, converge and diverge. Severe realism invades the sphere of intimate feelings. He forces both heroes to make, albeit incorrect, but independent decisions, often dictated not only by their hearts, but also by their minds:

A difficult year - illness broke me, Trouble overtook me, - happiness changed, - And neither enemy nor friend spares me, And even you did not spare! Tormented, embittered by the struggle With her blood enemies, Sufferer! you stand before me, a beautiful ghost with crazy eyes! Hair has fallen to the shoulders, Lips are burning, cheeks are blushing, And unbridled speech Merges into terrible reproaches, Cruel, wrong... Wait! It was not I who doomed your youth to a life without happiness and freedom, I am a friend, I am not your destroyer! But you don't listen...

In 1862, I.I. Panaev died. All friends believed that now Nekrasov and Avdotya Yakovlevna should finally get married. But this did not happen. In 1863, Panaeva moved out of Nekrasov’s apartment on Liteiny and very quickly married Sovremennik secretary A.F. Golovachev. This was a deteriorated copy of Panaev - a cheerful, good-natured rake, an absolutely empty person who helped Avdotya Yakovlevna quickly lose all her considerable fortune. But Panaeva became a mother for the first time, at the age of over forty, and became completely immersed in raising her daughter. Her daughter Evdokia Apollonovna Nagrodskaya (Golovacheva) would also become a writer - albeit after 1917 - in the Russian diaspora.

Split in Sovremennik

Already in the mid-1850s, Sovremennik contained all the best that Russian literature of the 19th century had and would have in the future: Turgenev, Tolstoy, Goncharov, Ostrovsky, Fet, Grigorovich, Annenkov, Botkin, Chernyshevsky, Dobrolyubov. And it was Nekrasov who collected them all into one magazine. It still remains a mystery how, besides high fees, the publisher of Sovremennik could keep such diverse authors together?

“Old” edition of the magazine “Sovremennik”: Goncharov I.A., Tolstoy L.N., Turgenev I.S., Grigorovich D.V., Druzhinin A.V., Ostrovsky A.N.

It is known that in 1856 Nekrasov concluded a kind of “binding agreement” with the leading authors of the magazine. The agreement obligated writers to submit their new works only to Sovremennik for four years in a row. Naturally, nothing came of this in practice. Already in 1858, I.S. Turgenev terminated this agreement unilaterally. In order not to completely lose the author, Nekrasov was then forced to agree with his decision. Many researchers regard this step by Turgenev as the beginning of a conflict in the editorial office.

In the acute political struggle of the post-reform period, two directly opposite positions of the main authors of the magazine became even more pronounced. Some (Chernyshevsky and Dobrolyubov) actively called Rus' “to the axe,” foreshadowing a peasant revolution. Others (mostly noble writers) took more moderate positions. It is believed that the culmination of the split within Sovremennik was the publication by N. A. Nekrasov, despite the protest of I. S. Turgenev, of an article by N. A. Dobrolyubova about the novel “On the Eve”. The article was titled “When Will the Real Day Come?” (1860. No. 3). Turgenev had a very low opinion of Dobrolyubov’s criticism, openly disliked him as a person and believed that he had a harmful influence on Nekrasov in matters of selecting materials for Sovremennik. Turgenev did not like Dobrolyubov’s article, and the author directly told the publisher: “Choose, either I or Dobrolyubov.” And Nekrasov, as Soviet researchers believed, decided to sacrifice his long-standing friendship with the leading novelist for the sake of his political views.

In fact, there is every reason to believe that Nekrasov did not share either one or the other views. The publisher relied solely on the business qualities of its employees. He understood that the magazine was made by common journalists (the Dobrolyubovs and Chernyshevskys), and with the Turgenevs and Tolstoys it would simply go down the drain. It is significant that Turgenev seriously suggested that Nekrasov take Apollo Grigoriev as the leading critic of the magazine. As a literary critic, Grigoriev stood two or three orders of magnitude higher than Dobrolyubov and Chernyshevsky combined, and his “brilliant insights” even then largely anticipated his time, which was later unanimously recognized by his distant descendants. But businessman Nekrasov wanted to make a magazine here and now. He needed disciplined employees, not disorganized geniuses suffering from depressive alcoholism. In this case, what was more important to Nekrasov was not old friendship, or even a dubious truth, but the fate of his favorite business.

It must be said that the official version of the “split of Sovremennik”, presented in Soviet literary criticism, is based exclusively on the memoirs of A.Ya. Panaeva is a person directly interested in considering the “split” in the magazine not just a personal conflict between Dobrolyubov (read Nekrasov) and Turgenev, but giving it an ideological and political character.

At the end of the 1850s, the so-called “Ogarevsky case” - a dark story with the appropriation of A.Ya. - received wide publicity among writers. Panaeva money from the sale of the estate of N.P. Ogarev. Panaeva volunteered to be a mediator between her close friend Maria Lvovna Ogareva and her ex-husband. As a “compensation” for N.P.’s divorce. Ogarev offered Maria Lvovna the Uruchye estate in the Oryol province. The ex-wife did not want to deal with the sale of the estate, and trusted Panaev in this matter. As a result, M.L. Ogareva died in Paris in terrible poverty, and where the 300 thousand banknotes proceeds from the sale of Uruchye went remains unknown. The question of how involved Nekrasov was in this case still causes controversy among literary scholars and biographers of the writer. Meanwhile, the inner circle of Nekrasov and Panaeva were sure that the lovers together embezzled other people’s money. It is known that Herzen (a close friend of Ogarev) called Nekrasov nothing more than a “sharp,” “thief,” “scoundrel,” and resolutely refused to meet when the poet came to him in England to explain himself. Turgenev, who initially tried to defend Nekrasov in this story, having learned about all the circumstances of the case, also began to condemn him.

In 1918, after the opening of the archives of the III department, a fragment of a illustrated letter from Nekrasov to Panaeva, dated 1857, was accidentally found. The letter concerns the “Ogarev case”, and in it Nekrasov openly reproaches Panaeva for her dishonest act in relation to Ogareva. The poet writes that he still “covers up” Avdotya Yakovlevna in front of his friends, sacrificing his reputation and good name. It turns out that Nekrasov is not directly to blame, but his complicity in a crime or its concealment is an indisputable fact.

It is possible that it was the “Ogarev” story that served as the main reason for the cooling of relations between Turgenev and the editors of Sovremennik already in 1858-59, and Dobrolyubov’s article about “On the Eve” was only the immediate reason for the “schism” in 1860.

Following the leading novelist and oldest employee Turgenev, L. Tolstoy, Grigorovich, Dostoevsky, Goncharov, Druzhinin and other “moderate liberals” left the magazine forever. Perhaps the above-mentioned “aristocrats” might also have found it unpleasant to deal with a dishonest publisher.

In a letter to Herzen, Turgenev will write: “I abandoned Nekrasov as a dishonest man...”

It was he who “abandoned” him, just as people are abandoned who have once betrayed their trust, are caught cheating in a card game, or have committed a dishonest, immoral act. It is still possible to have a dialogue, an argument, or defend one’s own position with an ideological opponent, but a decent person has nothing to talk about with a “dishonest” person.

At the first moment, Nekrasov himself perceived the break with Turgenev only as personal and far from final. Evidence of this is the poems of 1860, later explained by the phrase “inspired by the discord with Turgenev,” and the last letters to a former friend, where repentance and a call for reconciliation are clearly visible. Only by the summer of 1861 did Nekrasov realize that there would be no reconciliation, finally accepted Panayeva’s “ideological” version and dotted all the i’s:

We went out together... At random I walked in the darkness of the night, And you... your mind was already bright and your eyes were sharp. You knew that the night, the dead of night, would last our whole lives, And you did not leave the field, And you began to fight honestly. You, like a day laborer, went to work before light. You spoke the truth to the Mighty Despot. You did not let me sleep in a lie, branding and cursing, and boldly tore off the mask from the jester and scoundrel. And well, the ray barely flashed the Doubtful light, Rumor says that you blew out Your torch... waiting for the dawn!

"Contemporary" in 1860-1866

After a number of leading authors left Sovremennik, N.G. became the ideological leader and most published author of the magazine. Chernyshevsky. His sharp, polemical articles attracted readers, maintaining the competitiveness of the publication in the changed conditions of the post-reform market. During these years, Sovremennik acquired the authority of the main organ of revolutionary democracy, significantly expanded its audience, and its circulation continuously grew, bringing considerable profits to the editors.

However, Nekrasov's bet on young radicals, which looked very promising in 1860, ultimately led to the death of the magazine. Sovremennik acquired the status of an opposition political magazine, and in June 1862 it was suspended by the government for eight months. At the same time, he also lost his main ideologist N.G. Chernyshevsky, who was arrested on suspicion of drawing up a revolutionary proclamation. Dobrolyubov died in the fall of 1861.

Nekrasov, with all his revolutionary poetic proclamations (“Song to Eremushka”, etc.) again remained on the sidelines.

Lenin once wrote words that for many years determined the attitude towards Nekrasov in Soviet literary criticism: “Nekrasov, being personally weak, hesitated between Chernyshevsky and the liberals...”

It is impossible to come up with anything more stupid than this “classic formula”. Nekrasov never didn't hesitate and did not concede in any principled position or on any significant issue - neither to the “liberals” nor to Chernyshevsky.

Praised by Lenin, Dobrolyubov and Chernyshevsky were boys who looked up to Nekrasov and admired his confidence and strength.

Nekrasov could have been in a state of weakness, but, as Belinsky used to say about the famous Danish prince, a strong man in his very fall is stronger than a weak man in his very uprising.

It was Nekrasov, with his outstanding organizational skills, financial capabilities, unique social flair and aesthetic sense, who should have taken the role center, combiner, collision absorber. Any hesitation in such a situation would be fatal to the cause and suicidal for the one who hesitates. Fortunately, being personally strong, Nekrasov avoided both the unreasonable “leftism” of Chernyshevsky and the unpopular attacks of moderate liberals, taking in all cases a completely independent position.

He became “a friend among strangers and a stranger among his own.” Still, the old editors of Sovremennik, with which Nekrasov was connected by ties of long-standing friendship, turned out to be more “at home” with him than the young and zealous commoners. Neither Chernyshevsky nor Dobrolyubov, unlike Turgenev or Druzhinin, ever claimed friendship or personal relations with the publisher. They remained only employees.

In the last period of its existence, from 1863, the new editors of Sovremennik (Nekrasov, Saltykov-Shchedrin, Eliseev, Antonovich, Pypin and Zhukovsky) continued the magazine, maintaining the direction of Chernyshevsky. At that time, the literary and artistic department of the magazine published works by Saltykov-Shchedrin, Nekrasov, Gleb Uspensky, Sleptsov, Reshetnikov, Pomyalovsky, Yakushkin, Ostrovsky, and others. In the journalistic department, not the most talented publicists came to the forefront - Antonovich and Pypin. But this was not at all the same Sovremennik. Nekrasov intended to leave him.

In 1865, Sovremennik received two warnings; in the middle of 1866, after the publication of five books in the magazine, its publication was discontinued at the insistence of a special commission organized after Karakozov’s assassination attempt on Alexander II.

Nekrasov was one of the first to learn that the magazine was doomed. But he did not want to give up without a fight and decided to use his last chance. The story about “Muravyov’s ode” is connected with this. On April 16, 1866, in an informal setting of the English Club, Nekrasov approached the main pacifier of the Polish uprising of 1863, Count M.N. Muravyov, with whom he was personally acquainted. The poet read patriotic poems dedicated to Muravyov. There were eyewitnesses to this action, but the text of the poem itself has not survived. Witnesses subsequently claimed that Nekrasov’s “sycophancy” was unsuccessful, Muravyov treated the “ode” rather coldly, and the magazine was banned. This act dealt a serious blow to Nekrasov’s authority in revolutionary democratic circles.

In this situation, the surprising thing is not that the magazine was eventually banned, but how long it was not banned. Sovremennik owes its “delay” of at least 3-4 years exclusively to N.A.’s extensive connections. Nekrasov in the bureaucratic and government-court environment. Nekrasov was able to enter any door and could resolve almost any issue in half an hour. For example, he had the opportunity to “influence” S. A. Gedeonov, the director of the imperial theaters, a kind of minister, or his constant card partner A. V. Adlerberg, already then, without five minutes, the minister of the imperial court, a friend of the emperor himself. Most of his high-ranking friends did not care what the publisher wrote or published in his opposition magazine. The main thing is that he was a man of their circle, rich and well-connected. It never occurred to the ministers to doubt his trustworthiness.

But the closest employees of Sovremennik did not trust their publisher and editor at all. Immediately after the unsuccessful action with Muravyov and the closure of the magazine, the “second generation” of young radicals - Eliseev, Antonovich, Sleptsov, Zhukovsky - went to the accounting office of Sovremennik in order to obtain a full financial report. The “revision” by the employees of their publisher’s box office said only one thing: they considered Nekrasov a thief.

Truly “one of our own among strangers”...

Last years

After the closure of Sovremennik, N.A. Nekrasov remained a “free artist” with a fairly large capital. In 1863, he acquired the large Karabikha estate, becoming also a wealthy landowner, and in 1871 he acquired the Chudovskaya Luka estate (near Novgorod the Great), converting it specifically for his hunting dacha.

One must think that wealth did not bring Nekrasov much happiness. At one time, Belinsky absolutely accurately predicted that Nekrasov would have capital, but Nekrasov would not be a capitalist. Money and its acquisition have never been an end in itself, nor a way of existence for Nikolai Alekseevich. He loved luxury, comfort, hunting, beautiful women, but for full realization he always needed some kind of business - publishing a magazine, creativity, which the poet Nekrasov, it seems, also treated as a business or an important mission for the education of humanity.

In 1868, Nekrasov undertook a journalistic restart: he rented his magazine “Domestic Notes” from A. Kraevsky. Many would like to see a continuation of Sovremennik in this magazine, but it will be a completely different magazine. Nekrasov will take into account the bitter lessons that Sovremennik has gone through in recent years, descending to vulgarity and direct degradation. Nekrasov refused to cooperate with Antonovich and Zhukovsky, inviting only Eliseev and Saltykov-Shchedrin from the previous editorial office.

L. Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Ostrovsky, faithful to the memory of the “old” editors of Sovremennik, will perceive Nekrasov’s “Notes of the Fatherland” precisely as an attempt to return to the past, and will respond to the call for cooperation. Dostoevsky will give his novel “Teenager” to Otechestvennye Zapiski, Ostrovsky will give his play “The Forest,” Tolstoy will write several articles and will negotiate the publication of “Anna Karenina.” True, Saltykov-Shchedrin did not like the novel, and Tolstoy gave it to Russky Vestnik on more favorable terms.

In 1869, the “Prologue” and the first chapters of “Who Lives Well in Rus'” were published in Otechestvennye Zapiski. Then the central place is occupied by Nekrasov’s poems “Russian Women”, “Grandfather”, and the satirical and journalistic works of Saltykov-Shchedrin.

F. Viktorova - Z.N. Nekrasova

At the end of his life, Nekrasov remained deeply lonely. As the famous song goes, “friends don’t grow in gardens; you can’t buy or sell friends.” His friends had long ago turned their backs on him, his employees, for the most part, betrayed him or were ready to betray him, there were no children. Relatives (brothers and sisters) scattered in all directions after the death of their father. Only the prospect of receiving a rich inheritance in the form of Karabikha could bring them together.

Nekrasov also preferred to buy off his mistresses, kept women, and fleeting love interests with money.

In 1864, 1867 and 1869, he traveled abroad in the company of his new passion, the Frenchwoman Sedina Lefren. Having received a large sum of money from Nekrasov for services rendered, the Frenchwoman safely remained in Paris.

In the spring of 1870, Nekrasov met a young girl, Fyokla Anisimovna Viktorova. She was 23 years old, he was already 48. She was of the simplest origin: the daughter of a soldier or a military clerk. No education.

Later, there were also dark hints about the establishment from which Nekrasov allegedly extracted her. V. M. Lazarevsky, who was quite close to the poet at that time, noted in his diary that Nekrasov took her away from “some merchant Lytkin.” In any case, a situation has developed that is close to that once proclaimed in Nekrasov’s poems:

When from the darkness of delusion, with a hot word of conviction, I brought out a fallen soul, And all full of deep torment, You cursed, wringing your hands, the vice that entangled You...

Initially, apparently, Feklusha was destined for the fate of an ordinary kept woman: with accommodation in a separate apartment. But soon she, if not yet full, then after all mistress enters the apartment on Liteiny, occupying its Panaevsky half.

It is difficult to say in what role Nekrasov himself saw himself next to this woman. Either he imagined himself as Pygmalion, capable of creating his own Galatea from a piece of soulless marble, or with age, the complex of unrealized fatherhood began to speak more and more powerfully in him, or he was simply tired of the salon dryness of unpredictable intellectuals and wanted simple human affection...

Soon Feklusha Viktorova was renamed Zinaida Nikolaevna. Nekrasov found a convenient name and added a patronymic to it, as if he had become her father. This was followed by Russian grammar classes and the invitation of music, vocal and French teachers. Soon, under the name of Zinaida Nikolaevna, Fyokla appeared in society and met Nekrasov’s relatives. The latter strongly disapproved of his choice.

Of course, Nekrasov failed to turn a soldier’s daughter into a high-society lady and salon owner. But he found true love. The devotion of this simple woman to her benefactor bordered on selflessness. The middle-aged, experienced Nekrasov, it seemed, also sincerely became attached to her. It was no longer love-suffering or love-struggle. Rather, the grateful indulgence of an elder towards a younger, the affection of a parent for a beloved child.

Once, while hunting in Chudovskaya Luka, Zinaida Nikolaevna accidentally shot and mortally wounded Nekrasov’s favorite dog, the pointer Kado. The dog was dying on the poet’s lap. Zinaida, in hopeless horror, asked Nekrasov for forgiveness. He was always, as they say, a crazy dog lover, and would not forgive anyone for such a mistake. But he forgave Zinaida, as he would have forgiven not just another kept woman, but his beloved wife or his own daughter.

During the two years of Nekrasov’s fatal illness, Zinaida Nikolaevna was by his side, caring for him, comforting him, and brightening up his last days. When he passed away from the last painful battle with a fatal illness, she remained, as they say, an old woman:

For two hundred days, two hundred nights, my torment continues; Night and day My groans echo in your heart. Two hundred days, two hundred nights! Dark winter days, Clear winter nights... Zina! Close your tired eyes! Zina! Go to sleep!

Before his death, Nekrasov, wanting to ensure the future life of his last girlfriend, insisted on getting married and entering into an official marriage. The wedding took place in a military military church-tent, pitched in the hall of Nekrasov’s apartment. The ceremony was performed by a military priest. They were already leading Nekrasov by the arms around the lectern: he could not move on his own.

Nekrasov died for a long time, surrounded by doctors, nurses, and a caring wife. Almost all former friends, acquaintances, employees managed to say goodbye to him in absentia (Chernyshevsky) or in person (Turgenev, Dostoevsky, Saltykov-Shchedrin).

Crowds of thousands accompanied Nekrasov's coffin. They carried him in their arms to the Novodevichy Convent. Speeches were made at the cemetery. The famous populist Zasodimsky and the unknown proletarian worker, the later famous Marxist theorist Georgy Plekhanov and the already great writer-soilist Fyodor Dostoevsky spoke...

Nekrasov's widow voluntarily gave up almost the entire considerable fortune left to her. She transferred her share of the estate to the poet’s brother Konstantin, and the rights to publish works to Nekrasov’s sister Anna Butkevich. Forgotten by everyone, Zinaida Nikolaevna Nekrasova lived in St. Petersburg, Odessa, Kyiv, where, it seems, only once she loudly and publicly shouted out her name - “I am Nekrasov’s widow,” stopping the Jewish pogrom. And the crowd stopped. She died in 1915, in Saratov, stripped to the skin by some Baptist sect.

Contemporaries highly valued Nekrasov. Many noted that with his passing, the great center of gravity of all Russian literature was forever lost: there was no one to look up to, no one to set an example of great service, no one to show the “right” path.

Even such a consistent defender of the theory of “art for art’s sake” as A.V. Druzhinin argued: “... we see and will always see in Nekrasov a true poet, rich in future and who has done enough for future readers.”

F.M. Dostoevsky, delivering a farewell speech at the poet’s grave, said that Nekrasov took such a prominent and memorable place in our literature that in the glorious ranks of Russian poets he “is worthy to stand right next to Pushkin and Lermontov.” And from the crowd of the poet’s fans shouts were heard: “Higher, higher!”

Perhaps Russian society of the 1870s lacked its own negative emotions, thrills and suffering, which is why it so gratefully shouldered the depressive outbursts of poetic graphomaniacs?..

However, the closest descendants, capable of soberly assessing the artistic merits and shortcomings of Nekrasov’s works, rendered the opposite verdict: “singer of the people’s suffering”, “exposer of public ills”, “brave tribune”, “conscientious citizen”, able to correctly write down rhymed lines - this is not yet poet.

“An artist does not have the right to torture his reader with impunity and senselessly,” said M. Voloshin regarding L. Andreev’s story “Eliazar.” At the same time, it was no coincidence that he contrasted Andreev’s “anatomical theater” with Nekrasov’s poem, written upon his return from Dobrolyubov’s funeral...

If not in this, then in many of his other works N.A. For many years, Nekrasov allowed himself to torture the reader with impunity with pictures of inhuman suffering and his own depression. Moreover, he allowed himself to raise a whole generation of magazine critics and followers of the poetics of “people's suffering” who did not notice in these “tortures” anything anti-artistic, aggressive, or contrary to the feelings of a normal person.

Nekrasov sincerely believed that he was writing for the people, but the people did not hear him, did not believe in the simple peasant truth stylized by the master poet. Man is designed in such a way that he is interested in learning only the new, unfamiliar, unknown. But for the common people, there was nothing new or interesting in the revelations of the “people's saddener”. This was their daily life. For the intelligentsia it is the opposite. She believed Nekrasov, heard the bloody revolutionary alarm bell, got up and went to save the great Russian people. Ultimately, she died, falling victim to her own delusions.

It is no coincidence that none of the poems of “the most popular Russian poet” Nekrasov (except for “Peddlers” in various versions and “folk” adaptations) ever became a folk song. From “Troika” (its first part) they made a salon romance, omitting, in fact, what the poem was written for. Nekrasov’s “suffering” poems were sung exclusively by the populist intelligentsia - in living rooms, in exile, in prisons. For her it was a form of protest. But the people did not know that they also needed to protest, and therefore they sang apolitical ditties and the naive “Kalinka”.

Soviet art criticism, which rejected decadent abstruseness, like all the artistic achievements of the Russian “Silver Age,” again raised Nekrasov to unattainable heights and again crowned him with the laurels of a truly national poet. But it’s no secret that during this period people liked S. Yesenin more - without his early modernist twists and “folk” stylizations.

It is also significant that Soviet ideologists did not like Yesenin’s clear and clear voice. Only through the example of the “sufferer” Nekrasov could it be clearly proven: even before the revolution, before the rivers of shed blood, before the horrors of the Civil War and Stalin’s repressions, the Russian people were constantly groaning. This largely justified what was done to the country in 1920-30, justified the need for the most severe terror, violence, and physical extermination of entire generations of Russian people. And what’s interesting: in the Soviet years, only Nekrasov was recognized as having the right to hopeless pessimism and glorifying the theme of death in his lyrics. Soviet poets were persecuted at party meetings for such themes and were already considered “non-Soviet.”

In the few works of today's literary philologists, the activities of Nekrasov as a publisher, publicist, and businessman are often distinguished from literature and his poetic creativity. This is true. It's time to get rid of the textbook cliches that we inherited from the populist terrorists and their followers.

Nekrasov was, first of all, a man of action. And Russian literature of the 19th century was incredibly lucky in that N.A. Nekrasov chose it as the “work” of his entire life. For many years, Nekrasov and his Sovremennik constituted a unifying center, acting as a breadwinner, protector, benefactor, assistant, mentor, warm friend, and often a caring father for the people who made up the truly great edifice of Russian literature. Honor and praise to him for this both from his deceased contemporaries and from his grateful descendants!

Only merciless time has long ago put everything in its place.

Today, placing the poet Nekrasov above Pushkin, or at least on a par with him, would not occur to even the most loyal admirers of his work.

The experience of many years of school study of Nekrasov's poems and poems (in complete isolation from the study of the history of Russia, the personality of the author himself and the time context that should explain many things to the reader) led to the fact that Nekrasov had practically no fans left. To our contemporaries, people of the 20th-21st centuries, the “school” Nekrasov did not give anything except an almost physical disgust for the unknown why rhymed lines of satirical feuilletons and social essays “in spite” of that long-ago day.

Guided by the current legislation banning the promotion of violence, Nekrasov’s works of art should either be completely excluded from the school curriculum (for depicting scenes of human and animal suffering, calls for violence and suicide), or they should be carefully selected, providing accessible comments and links to the general historical context of the era .

Application

What feelings, besides depression, can such a poem evoke:

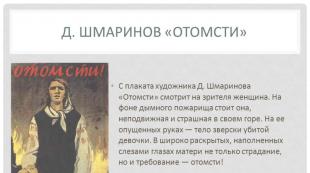

MORNING You are sad, your soul is suffering: I believe that it is difficult not to suffer here. Here nature itself is at one with the poverty that surrounds us. Infinitely sad and pitiful, These pastures, fields, meadows, These wet, sleepy jackdaws, That sit on top of the haystack; This nag with a drunken peasant, galloping through the force into the distance, hidden by the blue fog, this muddy sky... At least cry! But the rich city is no more beautiful: The same clouds are running across the sky; It's terrible for the nerves - with an iron shovel There they are now scraping the pavement. Work begins everywhere; The fire was announced from the tower; They brought someone to the shameful square - the executioners are already waiting there. The prostitute goes home at dawn Hastens, leaving the bed; Officers in a hired carriage are galloping out of town: there will be a duel. The traders wake up together and rush to sit behind the counters: They need to measure all day long, so that they can have a hearty meal in the evening. Chu! Cannons fired from the fortress! Flooding threatens the capital... Someone has died: Anna is lying on a red pillow of the First Degree. The janitor beats the thief - got caught! They drive a flock of geese to slaughter; Somewhere on the top floor a Shot was heard - someone had committed suicide. 1874Or this:

* * * Today I am in such a sad mood, So tired of painful thoughts, So deeply, deeply calm My mind, tormented by torture, - That the illness that oppresses my heart, somehow cheers me bitterly, - Meeting death, threatening, coming, I went myself would... But the dream will refresh - Tomorrow I will get up and run out greedily to meet the first ray of the sun: My whole soul will stir joyfully, And I will want to live painfully! And the illness, crushing strength, Will also torment tomorrow And about the proximity of the dark grave It is also clear to the soul to speak... April 1854

But this poem, if desired, can be brought under the law prohibiting the promotion of violence against animals:

Under the cruel hand of man, barely alive, ugly skinny, the crippled horse is straining, carrying an unbearable burden. So she staggered and stood. "Well!" - the driver grabbed the log (It seemed like the whip was not enough for him) - And he beat her, beat her, beat her! Its legs somehow spread wide, all smoking, settling back, the horse just sighed deeply and looked... (as people look, submitting to wrongful attacks). He again: along the back, on the sides, And running forward, over the shoulder blades And over the crying, meek eyes! All in vain. The nag stood, striped all over from the whip, only responding to each blow with a uniform movement of its tail. This made the idle passers-by laugh, Everyone put in a word of their own, I was angry - and thought sadly: “Shouldn’t I stand up for her? In our time, it’s fashionable to sympathize, We wouldn’t mind helping you, Unrequited sacrifice of the people, - But we don’t know how to help ourselves! " And it was not for nothing that the driver worked hard - Finally, he got the job done! But the last scene was more outrageous to look at than the first: The horse suddenly tensed up - and walked somehow sideways, nervously quickly, And the driver at each jump, in gratitude for these efforts, gave her wings with blows And he himself ran lightly next to him.

It was these poems by Nekrasov that inspired F.M. Dostoevsky to depict the same monstrous scene of violence in prose (the novel “Crime and Punishment”).

Nekrasov’s attitude towards his own work was also not entirely clear:

The celebration of life - the years of youth - I killed under the weight of labor And I was never a poet, the darling of freedom, A friend of laziness. If long-restrained torment boils up and approaches my heart, I write: rhyming sounds Disturb my usual work. Still, they are no worse than flat prose And they excite soft hearts, Like tears suddenly gushing from a saddened face. But I’m not flattered that any of them survives in people’s memory... There is no free poetry in you, My harsh, clumsy verse! There is no creative art in you... But living blood boils in you, A vengeful feeling triumphs, Burning love glows, - That love that glorifies the good, That brands the villain and the fool And bestows a crown of thorns on the Defenseless singer... Spring 1855

Elena Shirokova

Based on materials:

Zhdanov V.V. Life of Nekrasov. – M.: Mysl, 1981.

Kuzmenko P.V. The most scandalous triangles in Russian history. – M.: Astrel, 2012.

Muratov A.B. N.A. Dobrolyubov and I.S. Turgenev’s break with the magazine “Sovremennik” // In the world of Dobrolyubov. Digest of articles. – M., “Soviet Writer”, 1989

The personal life of Nikolai Alekseevich Nekrasov was not always successful. In 1842, at a poetry evening, he met Avdotya Panaeva (ur. Bryanskaya) - the wife of the writer Ivan Panaev.

Avdotya Panaeva, an attractive brunette, was considered one of the most beautiful women in St. Petersburg at that time. In addition, she was smart and was the owner of a literary salon, which met in the house of her husband Ivan Panaev.

S. L. Levitsky. Photo portrait of N. A. Nekrasov

Her own literary talent attracted the young but already popular Chernyshevsky, Dobrolyubov, Turgenev, Belinsky to the circle in the Panayevs’ house. Her husband, the writer Panaev, was characterized as a rake and a reveler.

Kraevsky House, which housed the editorial office of the journal Otechestvennye zapiski,

and also Nekrasov’s apartment was located

Despite this, his wife was distinguished by her decency, and Nekrasov had to make considerable efforts to attract the attention of this wonderful woman. Fyodor Dostoevsky was also in love with Avdotya, but he failed to achieve reciprocity.

At first, Panaeva also rejected twenty-six-year-old Nekrasov, who was also in love with her, which is why he almost committed suicide.

Avdotya Yakovlevna Panaeva

During one of the trips of the Panaevs and Nekrasov to the Kazan province, Avdotya and Nikolai Alekseevich nevertheless confessed their feelings to each other. Upon their return, they began to live in a civil marriage in the Panaevs’ apartment, together with Avdotya’s legal husband, Ivan Panaev.

This union lasted almost 16 years, until Panaev’s death. All this caused public condemnation - they said about Nekrasov that he lives in someone else’s house, loves someone else’s wife and at the same time makes scenes of jealousy for his legal husband.

Nekrasov and Panaev.

Caricature by N. A. Stepanov. "Illustrated Almanac"

prohibited by censorship. 1848

During this period, even many friends turned away from him. But, despite this, Nekrasov and Panaeva were happy. She even managed to get pregnant from him, and Nekrasov created one of his best poetic cycles - the so-called “Panaevsky cycle” (they wrote and edited much of this cycle together).

The co-authorship of Nekrasov and Stanitsky (pseudonym of Avdotya Yakovlevna) belongs to several novels that have had great success. Despite such an unconventional lifestyle, this trio remained like-minded people and comrades-in-arms in the revival and establishment of the Sovremennik magazine.

In 1849, Avdotya Yakovlevna gave birth to a boy from Nekrasov, but he did not live long. At this time, Nikolai Alekseevich also fell ill. It is believed that it was with the death of the child that strong attacks of anger and mood swings were associated, which later led to a break in their relationship with Avdotya.

In 1862, Ivan Panaev died, and soon Avdotya Panaeva left Nekrasov. However, Nekrasov remembered her until the end of his life and, when drawing up his will, he mentioned her in it to Panaeva, this spectacular brunette, Nekrasov dedicated many of his fiery poems.

In May 1864, Nekrasov went on a trip abroad, which lasted about three months. He lived mainly in Paris with his companions - his sister Anna Alekseevna and the Frenchwoman Selina Lefresne, whom he met in St. Petersburg in 1863.

ON THE. Nekrasov during the period of "Last Songs"

(painting by Ivan Kramskoy, 1877-1878)

Selina was an ordinary actress of the French troupe performing at the Mikhailovsky Theater. She was distinguished by her lively disposition and easy character. Selina spent the summer of 1866 in Karabikha. And in the spring of 1867, she went abroad, as before, together with Nekrasov and his sister Anna. However, this time she never returned to Russia.

However, this did not interrupt their relationship - in 1869 they met in Paris and spent the whole of August by the sea in Dieppe. Nekrasov was very pleased with this trip, also improving his health. During the rest, he felt happy, the reason for which was Selina, who was to his liking.

Selina Lefren

Although her attitude towards him was even and even a little dry. Having returned, Nekrasov did not forget Selina for a long time and helped her. And in his dying will he assigned her ten and a half thousand rubles.

Later, Nekrasov met a village girl, Fyokla Anisimovna Viktorova, simple and uneducated. She was 23 years old, he was already 48. The writer took her to theaters, concerts and exhibitions to fill the gaps in her upbringing. Nikolai Alekseevich came up with her name - Zina.

So Fyokla Anisimovna began to be called Zinaida Nikolaevna. She learned Nekrasov's poems by heart and admired him. Soon they got married. However, Nekrasov still yearned for his former love - Avdotya Panaeva - and at the same time loved both Zinaida and the Frenchwoman Selina Lefren, with whom he had an affair abroad.

He dedicated one of his most famous poetic works, “Three Elegies,” only to Panaeva.

2

It is also worth mentioning Nekrasov’s passion for playing cards, which can be called a hereditary passion of the Nekrasov family, starting with Nikolai Nekrasov’s great-grandfather, Yakov Ivanovich, an “immensely rich” Ryazan landowner who quite quickly lost his wealth.

However, he got rich again quite quickly - at one time Yakov was a governor in Siberia. As a result of his passion for the game, his son Alexei inherited only the Ryazan estate. Having married, he received the village of Greshnevo as a dowry. But his son, Sergei Alekseevich, having mortgaged Yaroslavl Greshnevo for a period of time, lost him too.

Alexey Sergeevich, when telling his son Nikolai, the future poet, his glorious pedigree, summarized:

“Our ancestors were rich. Your great-great-grandfather lost seven thousand souls, your great-grandfather - two, your grandfather (my father) - one, I - nothing, because there was nothing to lose, but I also like to play cards.”

And only Nikolai Alekseevich was the first to change his fate. He also loved to play cards, but became the first to not lose. At a time when his ancestors were losing, he alone won back and won back a lot.

The count was in the hundreds of thousands. Thus, Adjutant General Alexander Vladimirovich Adlerberg, a famous statesman, minister of the Imperial Court and personal friend of Emperor Alexander II, lost a very large sum to him.

And Finance Minister Alexander Ageevich Abaza lost more than a million francs to Nekrasov. Nikolai Alekseevich Nekrasov managed to return Greshnevo, where he spent his childhood and which was taken away for his grandfather’s debt.