Druids and the religion of the ancient Celts. Celtic primitive religion

If the last chapters of this book were the longest in comparison with the rest, it was because religion and art - along with learning - formed the lion's share of the entire background against which the life of the Celtic aristocrat took place. We know comparatively less about the lower social strata and their daily life, both spiritual and material; We can only guess about much of this. The literature of the ancient Celtic world, as well as the mentions of ancient authors about barbarians, speak only of the thoughts and actions of learned people and landowners in Celtic society. The tangible Celtic antiquities that archeology reveals also show those aspects of life most closely associated with the prosperity of society: burials, weapons and personal ornaments, horse harnesses; houses and fortresses of wealthy aristocrats. The unfree members of society and the lower stratum of free people had almost no ceramics and metal objects that could survive to this day; modest houses required almost no permanent foundation, which would have left postholes that an archaeologist could also find. The situation was very reminiscent of the Scottish mountains in the 18th century. Describing his journey with Dr. Johnson, Boswell remarks: “When we had already advanced sufficiently on this side of Loch Ness, I noticed a small hut, in the doorway of which stood a woman who appeared to be elderly. I thought the spectacle might amuse Dr. Johnson; so I told him about it. “Let's go in,” he suggested. We dismounted and, together with our guides, went into the hut. It was a tiny, miserable hut, it seemed to me, built from nothing but earth. The window was replaced by a small hole; it was plugged with a piece of peat, which was sometimes removed to let in light. In the middle of the room, or rather the space we entered, there was a fireplace that was heated with peat. Smoke came out through a hole in the roof. This woman had a pot on the fire in which goat meat was boiling.”

Probably, a similar scene could be observed in the world of the Iron Age: modest temporary dwellings and poor property - that’s all that representatives of the lower classes saw in their lives. Although information about other, non-aristocratic elements of Celtic society is inherently scant, there are certain factors - primarily related to the survival of Celtic culture on the periphery of the Western world - which lead us to assume that the humbler members of society, despite all the wretchedness home and lack of possessions, they were nevertheless, like their modern brethren, characterized by a deep reverence for art, intellect and learning, as well as for the gods and those who serve them. They could (and undoubtedly did) appeal to the local spirits and forces of nature, which they believed to control their own humble destiny, without recourse to the great deities of the upper classes and the aristocratic priests who supplicated these gods on behalf of the entire tribe. Probably, ordinary people observed certain ritual days and performed sacred rites that were known only to themselves and their equals in social status; if necessary, they could make sacrifices in their own special way and firmly believed in the power of the water of revered local wells, which helped the sick and made the barren fertile. However, all our evidence indicates that they, like members of the tribe, took part in the great tribal meetings and were present at the vital sacrifices on which the welfare of the whole people depended. Caesar himself writes: “If anyone - whether it be a private person or a whole people - does not obey their determination, then they excommunicate the culprit from the sacrifices. This is their heaviest punishment. Anyone who is excommunicated in this way is considered an atheist and a criminal, everyone shuns him, avoids meeting and talking with him, so as not to get into trouble, as if from an infectious disease; no matter how much he strives for it, no judgment is carried out for him; He also has no right to any position.”

Everything we know about modern farm laborers and tenant farmers in areas that are still Celtic forces us to assume that their brethren in the pagan Celtic world had the same reverence for intelligence and spirituality and all their manifestations in culture and that this was not at all influenced by them. more than a modest lifestyle. Both laborer and landowner could not imagine the great gods and semi-divine heroes without certain intellectual aspects, although these ideas were very limited. At no level in Celtic society would a jester, a handsome but brainless hero, or a lovely but stupid goddess be tolerated. It is often believed that the god Dagda was a kind of positive jester, but there is no real data on this matter: apparently, all the blame lies with hostile or humorous scientists who turned the powerful god of the tribe into some kind of good-natured buffoon.

Both gods and heroes were imagined as highly intellectual, having comprehended all the secrets of learning, poets and prophets, storytellers and artisans, magicians, healers, and warriors. In short, they had all the qualities that the Celtic peoples themselves admired and desired to possess. It was a divine reflection of everything that was considered enviable and unattainable in human society.

Thus, religion and superstition played a defining and profound role in the daily life of the Celts. This is in fact the key to any attempt to understand their peculiar character. Caesar writes: “All the Gauls are extremely pious.” All our data supports this assertion, and we do not need to look for some hidden political background here. Perhaps more than other peoples, the Celts were imbued with and constantly occupied with their religion and its outward expression, which was constantly and directly in the foreground of their lives. The deities and that Other World in which they were believed to live (when they were not invading the world of people, which they did quite often), were not just some theoretical ideas that could be remembered at a convenient time - on holidays or then, when it was necessary to celebrate a victory, at moments of national sacrifices or troubles (tribal or personal), or when it was necessary to receive something specific from them. They were omnipresent, sometimes menacing, always vengeful and ruthless. In the everyday life of the Celts, the supernatural was present along with the natural, the divine - with the ordinary; for them the Other World was as real as the substantial physical world, and just as omnipresent.

It should be emphasized from the outset that it is not easy to learn anything about the pagan Celtic religion. Just as the elements on which it was ultimately based were varied and elusive, so the sources for such research may be very varied, unequal in time and quality, scanty and scattered. The daily life of the ancient Celts as a whole, the nature of their behavior in society, their tribal structure, their laws and their characteristic style of art should be studied in order to better understand the rules and prohibitions that governed their religious behavior.

Ancient Celtic society was essentially decentralized. Its characteristic tribal system led to many local variants, but these variants continued to be part of a single whole. We know that at the zenith of their power the Celts occupied very large areas of Europe. As we have already seen, their territory extended from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Black Sea in the east, from the Baltic in the north to the Mediterranean in the south. But, despite the enormous differences and the long period of time that passed between the formation of a society rightly called Celtic and 500 AD. e., despite all the tribal characteristics, preferences and possible variations in linguistic dialects and economic system throughout this region, as well as between the continent and the British Isles - in short, despite all this, one can indeed talk about a Celtic religion, although not about the religious system, about the similarity of rituals and the unity of types of cult, about the same mixture of the natural and the supernatural. All this speaks of a deep and truly remarkable religious uniformity.

There are various sources of information about the pagan Celtic religion, and their fragmentary nature makes their use very risky, since the problem arises: how to connect them with each other and convincingly prove this connection? However, by combining the data of several sciences and comparing several sources, we can get a very general idea of the nature of the beliefs and rituals of the Celts.

First of all, we must consider the main sources on the pagan Celtic religion. The most important source we do not have is the texts that were written in their own language or Latin or Greek by the Celts themselves and which would give us a strictly Celtic view, from within society. There are simply no such sources. The Celts did not bother to write down their laws, genealogies, history, poetry or religious precepts. They considered them almost something sacred. Some Celts, as we have already seen, did use Greek for business purposes. But there can be no doubt that the Celts did not want their traditional traditions and learning to become accessible to godless strangers; these secrets were carefully guarded by those responsible for their perpetuation. Moreover, the reliance on oral memory is one of the most prominent characteristics of their culture, and it is still preserved and highly revered in those areas of the modern world where Celtic languages are spoken.

Thus, all these traditional disciplines had to be transmitted orally from teacher to student and from generation to generation. As we know, the future druid needed about 20 years to master all the secrets of his profession and fully assimilate them. Similarly, in Ireland, the filid had to study from 7 to 12 years in order to orally study all the complex subjects in which he studied. Oral tradition and its persistence is one of the most characteristic features of Celtic culture. In Ireland there were no ancient texts that could complement the information of archeology in the study of religion, however, there is a local literature, as in Wales, and although the legends and mythological episodes were actually recorded quite late - starting from the 7th-8th centuries - they obviously relate to events much more archaic than the period in which they were given literary form.

Due to the lack of direct written information from the Celts themselves, we are forced to look elsewhere for all the information we can gather. This information is mainly of three types and should be treated with great caution. If we see that different sources of information combine and confirm each other, then we are on relatively solid ground.

In some ways, archeology is the most reliable of the three sources mentioned, but it is inherently limited and lacks the detail that written records provide. Another source - data from ancient authors - gives us fascinating information about various aspects of Celtic religious life. But it is not always clear to what period this information belongs, whether it is based only on rumors or represents a record of what the author himself saw. The last source - local literature - is the most vivid and detailed evidence of the pagan Celtic religion, but it is so saturated with interpolations on the part of Christian scribes, fairy tales and folklore motifs common to all peoples that it must be handled very carefully and resisted the temptation to freely use it. interpret.

Overall, we have enough information about the Celtic religion to form a complete and convincing picture from the many pieces of information we have. To some extent it is possible to determine what was universal in their religious practices and what was their own, only Celtic, as well as the individual ways in which they expressed belief in the supernatural.

Having briefly analyzed the nature of the sources and made sure that the Celts really had a religion, we will try to find out more about it. What was most typical about it, what were its main features and religious cults?

The Celts had certain places where they addressed the deities, and there were also priests who prayed to the gods on behalf of the tribe. There were holy days, periods of celebration, and cult legends that explained the origins of these holidays. Since these are all aspects of the religious practice on which everything else depended, it will be useful to first try to get a general idea of them before considering the gods and goddesses themselves.

Temples, shrines and sanctuaries

In recent years, archaeologists have discovered some structures that completely change previous ideas about the nature of pagan Celtic temples and places of worship. It was previously believed that, with very minor exceptions (such as the elaborate temples built in Mediterranean style at Roquepertuse and Entremont near the mouth of the Rhone), the Celts had nothing even remotely resembling temples for religious activity. It was believed that the Celtic priests - the Druids - carried out their rituals and made sacrifices to the gods only in nature - for example, in groves of trees that were considered sacred due to their long-standing connection with the gods, or near sacred springs, the waters of which had special properties and through which one can was to gain access to the patron deity. Later, under the auspices of the Christian Church, these local deities were replaced by local saints, who often bore the same names as their pagan prototypes, and the veneration of wells continued in all its originality. Favorite places were the tops of sacred hills or the vicinity of mounds associated with some deified ancestor; however, it was believed that temples as buildings did not exist.

Now archaeologists are beginning to recognize and discover a number of monuments that represent the sanctuary buildings of the pagan Celts. Many of them were found in Europe, and some in Britain. Further research and excavation, as well as revision of the results of earlier excavations, will undoubtedly lead to new discoveries. In some cases it may be that a misinterpretation of the nature of such structures has actually obscured their true meaning; there are probably many more of them in the British Isles than we now think.

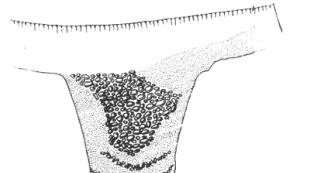

Rice. 37. Plans of firekshanzen - places of pagan cult, surrounded by earthen fences.

These buildings are rectangular earthen structures, which in Europe are called firekschanzen, that is, square fences. Overall they appear to date from the 1st century BC. e., and from a cultural point of view go back to the square burial enclosures of the Iron Age and are continued in Gallo-Roman temples, which were usually built of stone and were square or round in plan. Some Vierekschanzen, such as Holzhausen, Bavaria (Figs. 37, 38), had pits or shafts for offerings. Here, under two earthen ramparts, standing very close to each other, there were log palisades. Inside the enclosure there were deep shafts in which traces of offerings were found, including meat and blood, probably sacrificial ones. In one of these fences the remains of a temple built from logs were found.

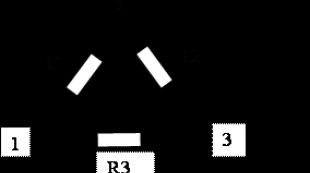

Rice. 38. Ritual mine. Holzhausen, Bavaria.

Many deep shafts, mostly circular in cross-section, have been found in Britain. Some of them were discovered during excavation work during the construction of railways in the 19th century. Unscientific excavations and recordings have caused great damage and loss of materials; Traces of mine-related buildings or earthworks were often overlooked or described so inaccurately that in most cases the information was virtually useless. The mine, excavated in Wilsford (Wiltshire), was dated using radiocarbon dating to the 14th century BC. BC, and this suggests that religious buildings and centers of ritual activity of this type existed long before the Celts. All this makes us reconsider the origins of the Celtic priests - the Druids, who, of course, used such sanctuaries in Celtic times.

One vague testimony of Athenaeus, which we have already touched upon in another context, makes us think of precisely such rectangular ritual fences.

“In the story of Lovernius, the father of that Bituitus who was killed by the Romans, Posidonius writes that, seeking the love of the people, he rode through the fields in a chariot, scattering gold and silver to tens of thousands of Celts accompanying him; Having fenced off a rectangular space with a side of twelve furlongs, he placed vats there filled with expensive wine, and he prepared such mountains of food that for many days in a row he could treat everyone who wanted it, without experiencing a shortage of anything.”

From Irish sources we know that the ritual gatherings of the Celts were accompanied by lavish feasts and copious libations, and that games, horse racing and trade played an essential role in the solemn religious festivals. One of the most interesting and impressive discoveries in recent times was the 1956 excavation of a striking Celtic sanctuary at Libenice, near Kolin in the Czech Republic. In a long enclosure surrounded by a rampart and a ditch, evidence of child and animal sacrifices, a human skull that could have been used for ritual libations, a platform for sacrifices, pits with bones and a huge amount of dishes, also broken for ritual purposes, were discovered. Two twisted bronze torques, apparently, originally covered the necks of two huge wooden idols: only the holes from the pillars remained - the idols themselves were not preserved. The burial of an elderly woman, possibly a priestess of this sanctuary, was discovered; it contained brooches, ceramics and other objects that allow us to date the sanctuary to the 3rd century BC. e.

A much earlier, but very similar structure was discovered at Aunet-aux-Planches (Marne department); it belongs to the era of the burial field culture and dates back to the 11th century BC. e. It is also possible that the long enclosure at Tara, commonly called the Mead Hall, one of the most important sacred places of ancient Ireland, is another example of such a structure. The heirs of these various buildings were, on the one hand, stone Romano-Celtic temples, and on the other, the fenced Roman cemeteries of Gaul and Britain.

Thus, our data shows that the Celts were far from worshiping their gods only in groves and other places in nature: in fact, they had a wide variety of buildings in which they performed their rites. There is no doubt that future archaeological surveys on the continent and the British Isles will reveal many more of them. There is also a number of evidence of wooden temples inside these areas, fenced with earthen ramparts.

In Celtic the sanctuary was called nemeton; there is no reason to assume that similar fences were not also called this word, although it could also refer to clearings in groves that also served as sacred places. In Old Irish this word sounds like "nemed"; There is also the word “fidnemed” - “sacred grove”. Place names indicate that the word was widely used in the Celtic world. So, in the 6th century AD. e. Fortunatus mentions a place called Vernemet(on) - “Great Sanctuary”; there was a place with the same name in Britain, somewhere between Lincoln and Leicester. The city of Nanterre was originally called Nemetodur, and in Spain there is a place called Nemetobriga. Drunemeton is known - “Oak Sanctuary”, which was both a sanctuary and a meeting place for the Galatians, as well as many others. In Britain there is evidence of a place called Medionemeton ("Central Sanctuary") somewhere in Scotland, and at Buxton in Derbyshire there was a sacred spring called the "Acts of Arnemetia", that is, "the waters of the goddess Arnemetia", mistress of the spring and sacred grove.

Thus, the Celts not only worshiped their deities and performed expiatory rites in sacred clearings in forbidden groves. They built various earthen enclosures that either contained wooden temples or some key place for sacrifices and propitiation of the gods, such as a huge ritual pillar or column, a shaft or pit for throwing the remains of victims - both animals and people, and a repository for votive offerings of another kind. Undoubtedly, in most cases there must have been a rough hut - wicker or made of wood - which the priest could use to store the signs of his priestly dignity and ritual objects.

In such places the Celts worshiped their gods. Now we must try to find out who was the mediator between the gods and the believers. At least some of the Celtic priests were called Druids, and we have already spoken of them in connection with their place in society and their role as guardians of ancient tradition. We must now consider them in the light of religion, as priests. Most readers are familiar with the word “Druid” and imagine the romantic Celtic priests who performed their sacred rites, so colorfully described by Pliny: “They call the mistletoe by a name that means “all-healer.” Having prepared the sacrifice and feast under the trees, they bring there two white bulls, whose horns are then tied for the first time. The priest, dressed in a white robe, climbs the tree and trims the mistletoe with a golden sickle, and others catch it in a white cloak. They then kill the victims, praying that God will accept this propitiatory gift from those to whom he bestowed it. They believe that mistletoe, taken as a drink, gives fertility to infertile animals and that it is an antidote to all poisons. These are the religious feelings that many peoples experience over completely trivial matters.”

One might wonder if the mysterious beads on the horns of bulls in Celtic religious iconography suggest that the horns were tied together in preparation for sacrifice, indicating that these animals belonged to the gods or were the god himself in animal form. It is also interesting to note that the word for mistletoe in modern Irish and Scottish Gaelic is "uil-oc" literally meaning "all-healer". Pliny's story about this ritual, which accompanied the sacrifice of bulls, had a huge influence on subsequent attitudes to the question of the Celtic priesthood: there was no awareness of how limited our real information about the Druids is, and to a very large extent fantasy began to color the facts.

In fact, with the exception of some very scanty references to such a class of pagan priests in ancient authors and very vague references in local tradition, we know very little about the Druids. We do not know whether they were common throughout the Celtic world, whether they were the only high-ranking priests, or in what time period they were active. All we know is that at a certain period in history some of the Celtic peoples had powerful priests who were called that way; they helped defend against the forces of the Other World, often hostile, and with the help of rituals known only to them, they directed these forces for the benefit of humanity in general and this tribe in particular. The most in-depth analysis of the nature of Druidry is contained in S. Piggot's book “Druids”.

The fact that in our time so much attention is paid to the Druids is entirely due to the activities of antiquarian writers, starting from the 16th century. The whole "cult" of the Druids was connected with the concept of the "noble savage", and on a very meager basis of fact a whole fantastic theory was built, which led to the emergence of the modern "Druidic cult" which is practiced at Stonehenge. There is not the slightest evidence that the pagan priests of the ancient Celtic tribes were in any way connected with this Neolithic and Bronze Age monument (although their predecessors may have had something to do with it). Modern events such as the Eisteddfod - an annual celebration of music and Welsh culture in Wales - and other similar festivals throughout the still-Celtic world have helped to perpetuate the image of the idealized druid, but this image is inherently false, based not so much on surviving ones, but on reconstructed ones. traditions

The influence of the antiquarian philosophers was so great that there is virtually no Neolithic or Bronze Age henge that is not attributed to "Druid" origin or connection with the Druids. Throughout the British Isles, and especially in the Celtic regions, we find Druid circles, thrones, mounds, Druid stones. Dr. Johnson very astutely remarked about the first such monument he saw: “About three miles beyond Inverness we saw, just by the road, a very complete example of what is called a Druid temple. It was a double circle, one of very large stones, the other of smaller stones. Dr. Johnson rightly noted that “to go to see another Druid temple is only to see that there is nothing here, since there is neither art nor power in it, and seeing one is enough.”

The Celts themselves in pre-Christian times did not leave any evidence of their priesthood. The only mentions of Druids in Ireland, therefore, date back to times after paganism. It is unclear whether they accurately depict the character of the Druid, or whether what is said about the Druids is only the result of a negative attitude towards them on the part of the new priesthood that was hostile to them. In some cases the Druids, who are constantly mentioned, appear to be worthy and powerful people; sometimes they are even given preference over the king himself. Thus, in “The Rape of the Bull from Kualnge” the druid Cathbad is named the father of the king himself - Conchobar, the son of Ness. It says that Cathbad had a group of disciples whom he instructed in Druidic science. According to Irish tradition, he is depicted as a teacher who teaches the youth the religious traditions of the tribe and the omens by which these traditions can be turned to their advantage. This is consistent with the picture of Celtic priests painted by Caesar in the 1st century BC. BC: “Druids take an active part in matters of worship, monitor the correctness of public sacrifices, interpret all questions related to religion; Many young people come to them to study science, and in general they are held in great esteem by the Gauls.”

In one of the oldest of the Old Irish sagas, The Banishment of the Sons of Usnech, the dramatic event, the cry of the unborn femme fatale Deirdre in her mother's womb, must be explained through the prophetic powers of the Druid Cathbad. After this ominous event occurred, which frightened everyone present, the expectant mother rushes to the druid and begs him to explain what happened:

You better listen to Cathbad

Noble and beautiful,

Overshadowed by secret knowledge.

And I myself, in clear words...

Can not say.

Cathbad then “placed… his palm on the woman’s stomach and felt a thrill under his palm.

“Truly, this is a girl,” he said. “Her name will be Deirdre.” And a lot of evil will happen because of her.”

After this, a girl is really born, and her life really follows the path predicted by the Druid.

According to Irish tradition, Druids are characterized by dignity and power. Other references give them other, almost shamanistic, features. The name in question is the famous druid Mog Ruth: at least one specialist in Celtic mythology believed that he was originally a sun god. Although to claim this is to go much further than the available evidence allows us, he was nevertheless considered a powerful sorcerer and allegedly had the ability to raise a storm and create clouds with just his breath. In the saga "The Siege of Drum Damgaire" he wears enchennach - "bird clothes", which is described as follows: “They brought to him the skin of Mog Ruth's hornless brown bull and his motley bird clothes with flowing wings, and, in addition, his druid robes. And he rose together with the fire into the air and into the sky.”

Another account of the Druids from local Irish sources portrays them in a humorous light and as not being as worthy as antiquarian admirers would have them believe. However, perhaps the reason for this is the confusion of the word “druid” with druith - “fool”. In the saga "The Intoxication of the Ulads", which is full of mythological motives and situations, Queen Medb, an Irish goddess by origin, is guarded by two druids, Crom Derol and Crom Daral. They stand on the wall and argue. One thinks that a huge army is approaching them, while the other claims that these are all just natural parts of the landscape. But in reality it is really the army that is attacking them.

“They did not stand there for long, two druids and two observers, when the first detachment appeared in front of them, and its approach was white-bright, crazy, noisy, thundering over the valley. They rushed forward so furiously that in the houses of Temra Luachr there was not a sword left on a hook, not a shield on a shelf, not a spear on a wall that would not fall to the ground with a roar, noise and ringing. On all the houses in Temre Luakhra, where there were tiles on the roofs, those tiles fell from the roofs onto the ground. It seemed as if a stormy sea had approached the walls of the city and its fence. And in the city itself, people’s faces turned white, and there was gnashing of teeth. Then two druids fainted, and into unconsciousness, and into unconsciousness, one of them, Krom Daral, fell from the wall outside, and the other, Krom Derol, fell inside. But soon Krom Derol jumped to his feet and fixed his gaze on the detachment that was approaching him.”

The Druid class could have had some kind of power in the Christian era, at least in the Goydel world, and we have no reason to believe that with the advent of Christianity, pagan cults and all the attributes and people associated with it instantly disappeared. In Scotland, Saint Columba is said to have met a Druid named Broichan near Inverness in the 7th century AD. e. The Druids may have existed for some time under Christianity, although they no longer had the same religious power and political influence; perhaps they turned only into magicians and sorcerers.

However, in ancient times their power, at least in some areas of the Ancient World, was undeniable. Caesar, apparently, was basically right when he wrote: “Namely, they give verdicts in almost all controversial cases, public and private; whether a crime or murder has been committed, whether there is a dispute over inheritance or borders, the same Druids decide... Their science is thought to have originated in Britain and from there transferred to Gaul; and to this day, in order to get to know it more thoroughly, they go there to study it.”

In addition, Pliny mentions the veneration that Druidry enjoyed in the British Isles. He notes: “And to this day Britain is fascinated by magic and performs its rites with such ceremonies that it seems as if it were she who transmitted this cult to the Persians.”

Caesar, speaking about Britain, does not mention the Druids. Episodes such as the Boudicca revolt and the religious rites and practices associated with them give the impression that in the 1st century AD. e. there was something very similar to Druidry, at least in some parts of Britain. In fact, ancient authors have only one mention of Druids in Britain. Describing the attack of the Roman governor Paulinus on the Druid fortress on Anglesey in 61 AD. e., Tacitus says: “On the shore stood a fully armed enemy army, among which women were running, looking like furies, in mourning robes, with flowing hair, they were holding burning torches in their hands; The Druids who were right there, with their hands raised to the sky, raised prayers to the gods and uttered curses. The novelty of this spectacle shocked our warriors, and they, as if petrified, exposed their motionless bodies to the blows raining down on them. Finally, heeding the admonitions of the commander and urging each other not to be afraid of this frenzied, half-female army, they rush towards the enemy, throw them back and push the resisters into the flames of their own torches. After this, a garrison is placed among the vanquished and their sacred groves are cut down, intended for the performance of ferocious superstitious rites: after all, they considered it pious to irrigate the altars of the lairs with the blood of prisoners and ask for their instructions, turning to human entrails.”

We already know that the Druid stronghold on Anglesey may have been associated with both economic and religious aspects, which explains the fanatical resistance to the Roman invasion. Further archaeological excavations, along with the classification of some of the cult figures on Anglesey that have not yet been studied in this context, may shed more light on the nature of Druidry on this island, and perhaps in Britain as a whole.

Evidence from ancient authors suggests that female druids, or druidesses, if they can be called that, also played a role in the pagan Celtic religion, and this evidence is consistent with the data of the insular texts. Vopisk (although this is a rather dubious source) tells an interesting story: “My grandfather told me what he heard from Diocletian himself. When Diocletian, he said, was in a tavern in Tungri in Gaul, still had a small military rank and was summing up his daily expenses with some female Druidess, she said to him: “You are too stingy, Diocletian, too prudent.” To this, they say, Diocletian answered not seriously, but jokingly: “I will be generous when I become emperor.” After these words, the Druidess is said to have said: “Don’t joke, Diocletian, because you will be emperor when you kill the boar.”

Speaking about the prophetic abilities of the Druids and again mentioning women, Vopisk says: “He claimed that Aurelian once turned to the Gallic Druidesses with the question of whether his descendants would remain in power. Those, according to him, replied that there would be no more glorious name in the state than the name of the descendants of Claudius. And there is already Emperor Constantius, a man of the same blood, and his descendants, it seems, will achieve the glory that was predicted by the Druidesses.”

We have already seen what prophetic power is attributed to the seer Fedelm in The Rape of the Bull from Kualnge; there is every reason to believe that in the Druid class women, at least in some areas and at some periods, enjoyed a certain influence.

Idols, images and votive offerings

We already know something about the temples and sanctuaries of the Celts and about the Druids who were priests of at least some of the Celts. Now the next question arises: were cult images made in pre-Roman times? Did the Celts worship their gods in a tangible form or did they simply imagine abstract concepts of divinity?

Rice. 39. Five of 190 objects (all from oak heartwood) discovered at the Sequana sanctuary at the mouth of the Seine River (Côte-d'Or, France).

All our data suggests that they had a wide variety of images and idols. Astounding evidence of this is a huge treasure of about 190 wooden objects from the site where the Temple of Sequana was located at the source of the Seine River. All are made from oak heartwood, as are many other iconic wooden objects from Denmark (where Celtic influence was strong), France and the British Isles. Such a large number of surviving images actually indicates that at one time they existed in huge numbers. Thus, the favorite material for making idols was wood, and since the Celts revered oak more than any other tree, the choice of oak for making idols was quite natural. Some philologists believe that the word “druid” itself is associated with the Celtic designation for oak, which itself is also associated with the Greek name for oak - drus. The second syllable of this word is possibly related to the Indo-European root "wid", meaning "to know"; that is, in general, "druid" means something like "a sage who reveres the oak tree." Maximus of Tyre says that the Celts imagined Zeus (meaning the Celtic equivalent of the ancient god) as a huge oak tree. Caesar says that Gaul has the most images of Mercury (again referring to the local gods who merged with Mercury in Roman times). All this suggests that the Celtic religion was by no means devoid of images, as is sometimes claimed - quite the contrary.

It is clear, however, that stone images were less popular, and although a small number are known from at least the 6th century BC. e., stone sculptures became truly revered only from the 1st century BC. e. under the auspices of the Roman world. However, there is also a lot of evidence that the stones themselves, decorated in the Celtic manner, like the stones from Turo or Castlestrange (Ireland), or the pillar from Sankt Goar (Germany), or simply stone blocks or standing stones, were revered in themselves: it was believed that they have amazing power. Stones, as we have already seen, often marked the boundaries between tribes. Lia Fal - the great inauguration stone of ancient Ireland - shouted when the true ruler of Ireland stood upon him. There are countless stories in the Old Irish tradition about the power of sacred stones. Today, in modern Celtic folk beliefs, some stones are still considered to have supernatural powers, and in remote areas of the existing Celtic world the use of stones in black magic and similar rituals is still remembered. In the Irish "Ancient Places" (stories explaining the origin of the names of certain places) there are references to the stone idol Cenn Croich, or Cromm Cruach (in modern folk legend - Crom Oak), and eleven of his brothers. Although this legend is of course not to be taken literally, there are elements of it that fit convincingly with the general picture of Celtic belief as we imagine it. Moreover, the fact that the idol supposedly stood on Mag Slecht, the "Valley of Worship" in the north-west corner of County Cavan, where there appears to have been a large cult area of primary importance in pagan times, emphasizes the truth behind the story. The legend says: “Here stood a tall idol that had seen many battles, and it was called Cromm Cruach; he forced all the tribes to live without peace... He was their god, ancient Kromm, hidden in many mists; as long as people believed in him, they could not find the eternal Kingdom above all refuges... Stone idols stood in rows, four rows of three; and oh woe, in order to deceive the troops, the image of Kromm was made of gold. From the reign of Eremon, a generous leader, stones were revered here until the arrival of the noble Patrick in Ard Macha. He smashed Kromm with a hammer from head to toe; with his great courage he drove out the powerless monster that stood here.”

This colorful account of the overthrow of pagan idols by the Christian church may explain the paucity of stone sculptures in the pre-Roman Celtic world.

Cromm, or Cenn Cruach, remained in Irish folk tradition as Crome Oak. Moira McNeill, along with other scholars, analyzes the legends of this cult figure in connection with the great calendar festival of Lughnasadh. Another stone idol is described in the Irish Calendar of Aengus: “Clohar, that is, the golden stone, that is, the stone set in gold, which was revered by the pagans, and a demon named Kermand Kestah used to speak from this stone, and it was the chief idol of the North "

Another idol, this time supposedly British, was called Etarun. This name may contain the same root as the name of the great Gallic god with the wheel - Taranis, traces of whose cult are actually observed in Britain. It was not only gods or demons who were believed to dwell in the stones and speak from them; weapons were also considered the home of spirits. People believed that the sacred weapons of gods and semi-divine heroes could act and speak independently of the owner through the actions of supernatural forces that controlled them. In The Rape of the Bull of Cualnge we read how Sualtaim, the earthly father of Cuchulainn, is killed by his own shield: he violated the custom that no one should speak before the Druid spoke:

“Then Sualtaim left them in anger and rage, because he did not hear the desired answer. And it so happened that the Gray of Macha reared up and galloped away from Emain, and the shield of Sualtaim slipped out of his hands and cut off his head with its edge. Then the horse turned back towards Emain, and on its back lay a shield with the head of Sualtaim. The head said again:

“Husbands are killed, women are taken away, cattle are kidnapped, O Ulads!”

The number of small initiatory models of weapons such as spears, swords and shields found in ritual contexts in Britain and on the Continent also suggests that the weapon was considered the home of supernatural powers. Some of these miniature objects were deliberately broken, no doubt in accordance with the rituals and beliefs that existed at the time. Daggers with handles in the shape of people (Fig. 40) depicted the very spirit or deity that supposedly lived in them or was responsible for their origin. This is another source of evidence regarding the veneration of these objects in the ancient Celtic world.

Rice. 40. Man-shaped short sword handle from North Grimston, Yorkshire, East Riding.

The art of La Tène, as we will see in the next chapter, turned out to be another treasure trove of cult symbols. All were delicately woven into fluid patterns of spirals, stylized foliage and plants; the torques itself (neck decoration) served as a magical insignia worn by gods and heroes. On many decorated items of horse harness and helmet decorations we see symbols of magical power and amulets against evil.

The Celts were by no means ignorant of everything related to the veneration of idols and anthropomorphic images - it can be considered proven that they had plenty of all this. But since they tended to express their beliefs and ideas indirectly, this is not always obvious, and only a study of Celtic culture and everyday life in general can reveal the subtle influence of religion and superstition in many ways that at first glance seem mundane and ordinary.

Holidays and ritual gatherings

We looked at the sanctuaries and sacred sites of the Celts and learned that there were many of them, although many have only been discovered in recent years, and some are still awaiting discovery. We have become acquainted with those who had to speak to the gods on behalf of mankind, and have discovered that the Celts certainly had priests called Druids, and there is evidence of the existence of other priests, although we do not know what role they played and how they were connected with the Druid class. We have seen that the Celts had idols and cult images in abundance, and in the future many of them will undoubtedly be discovered or found in literary contexts.

And finally, let's try to figure out in what cases all these items were used? What rituals did the priests perform in the sanctuaries where many of the idols and other paraphernalia of the religious cult were located?

The Celts celebrated the main calendar holidays. We already know that the Celts considered time to be nights. The Celtic year in Ireland was divided into four main parts, and it is quite possible that this was done in other parts of the Celtic world. Each part of the year began with a great religious festival, at which some cult legend was remembered. The holiday was accompanied by feasts and fun, fairs and bazaars, games and competitions, as well as solemn religious rites, and in Gaul, at least, sacrifices of both people and animals. This custom was abhorred by the Romans, who had long abandoned the practice of human sacrifice by the time they came into close contact with the pagan Celtic world.

The first ritual stage of the calendar year was February 1st. This holiday was apparently dedicated to the goddess Brigid, whose place was later taken by her Christian successor, Saint Brigid. This powerful goddess was also known as Brigantia, the patron goddess of northern Britain. Dedications and names of places on the continent also speak of her cult. She was most likely one of the most revered goddesses of the entire pagan Celtic world. What the holiday in her honor, which was called Imbolc (or Oimelg), was not entirely clear, however, apparently, it was associated with the beginning of milking of sheep and, thus, was primarily a holiday of shepherds. In the later Christian tradition, attention is drawn to Brigid's connection with sheep and shepherd life, as well as with fertility in general; apparently, these are echoes of the role played by its pagan predecessor.

The second holiday, Beltane, was celebrated on May 1. It may have been associated with the veneration of the ancient Celtic god Belenus, who is known from some 31 inscriptions discovered in northern Italy, southeastern Gaul and Norica. There are also epigraphic traces of his cult in the British Isles, and some evidence from the literary tradition suggests that traces of knowledge about this deity persisted in the Celtic world even later. Beli Mawr, who appears in the Mabinogion as a powerful king of Britain, appears to have been considered an ancestor deity of the aristocracy of early Wales and can be identified in origin with Bhelen himself. The power and influence of this early pastoral deity may explain the popularity and longevity of his festival, which still survives in at least some areas of the Scottish Highlands. According to Cormac, the 9th-century author of an Old Irish dictionary, the word "Beltane" comes from "Beltene" - "beautiful fire". It was a holiday associated with the promotion of fertility, and magical rites occupied a large place in it, designed to ensure the reproduction of livestock and the growth of crops. Large fires were lit and cattle were driven between the fires for purification. Again, according to Cormac, the Druids lit two fires and drove animals between them. Undoubtedly, sacrifices were made at these festivals. Beltane was also called "Ketsamain".

The third seasonal festival was also widespread throughout the Celtic world, and traces of it are still alive in modern Celtic folk customs. Celebrated on August 1, Lughnasadh was primarily an agricultural festival, associated with the harvest of grain rather than with a pastoral economy. He was closely associated with the god Lugh in Gaul (Lugh in Ireland, Lleu in Wales), a powerful, widely worshiped deity whose cult may have been introduced to Ireland by later Celtic settlers. In Roman Gaul, in Lyon (Lugdunum), a holiday was celebrated on this day in honor of the Emperor Augustus, and it seems quite obvious that it replaced the old holiday dedicated to the Celtic god, after whom the city was called the “fortress of Lug.” Lughnasadh was a very important holiday in Ireland, as the folklore that has come down to us confirms. This holiday was sometimes called Bron Trogain - "Sorrow of Trogan", and perhaps this is the old name of Lughnasad. In Ireland, two large gatherings were traditionally held on Lughnasadh, both associated with powerful goddesses. One of these holidays was the festival of Tailtiu, the other was the festival of Karman. The Tailtiu festival took place in Teltoun, County Meath. There are two legends that explain the origin of this holiday. One says that it was erected by the god Lugh in honor of his adoptive mother Tailtiu, who died here on 1 August. We have already realized how important the educational system was to Celtic society and that (ideally) adoptive parents were treated with respect and love. Apparently, the same thing happened among the gods.

The Lughnasadh holiday traditionally lasted a whole month - 15 days before August 1 and 15 days after. Other traditions say that Lugh founded the festival of Tailtiu in honor of his two wives, Nas and Bui. In Ulster Lughnasadh was celebrated at Emain Macha, in Leinster at Carman. It was believed that Carman was the mother of three sons: together with her sons, she devastated all of Ireland, she - in a purely feminine way, using magic and witchcraft, they - resorting to their strength and weapons. Finally the sons were defeated and forced to leave Ireland, and Carman remained here as a hostage "along with the seven things that they revered." She died of grief, and a holiday was held in her honor, in accordance with her wishes.

The fourth festival - in fact the first of the Celtic year, since it marked the beginning of it - was Samhain, perhaps the most important of the four. On this day, the Other World became visible to people and all supernatural forces roamed freely in the human world. It was a time of terrible danger and spiritual vulnerability. It was celebrated on the night of November 1 and throughout that day. In the ancient Irish sagas, this is a very significant holiday, and most events that have mythological and ritual significance are dedicated to this date. It was the end of the shepherd's year and the beginning of the next; undoubtedly, on this day sacrifices were made, which were supposed to appease the forces of the Other World and scare away hostile creatures.

On Samhain, the Dagda, the tribal deity of the Irish, entered into sacred marriage with Morrigan, the raven goddess of war; on the battlefield she acted not with the help of weapons, but by magically intervening in the battle. Throughout the early tradition the inherent gift of prophecy is emphasized. She could be both a good friend and a ruthless enemy. On another occasion, the Dagda united with the river goddess, patron of the Boyne River.

In remote areas the festival of Samhain is still celebrated among the Celtic peoples, and until recently a very elaborate ritual was observed on this day. It was a night of fortune-telling and magic: the correct rituals had to be performed in order to propitiate the supernatural forces that were believed to be scattered throughout the human world at this time.

There were, of course, other holidays in the ancient Celtic world. It was the festival of Thea, patroness divine of the Assembly of Tara, one of the greatest shrines in Ireland; she was also held captive, like Karman and Tailtiu. Another patroness of the festival, Tlachtga, allegedly gave birth to three twins at once (a typical Celtic mythological motif), and all had different fathers. Like the goddess Maha, she died in childbirth. These ancient goddesses apparently played a role in the ritual festivals of the ancient Celtic calendar.

Severed heads

Now from sanctuaries and temples, priests and idols, periodic holidays and ritual meetings, we move on to consider the nature of those very deities for whom this entire system of religious rites was designed. However, before talking about the character of some individual deities and their cults, we, perhaps, will build a bridge to this topic by considering the symbol in which to some extent the entire pagan Celtic religion was focused and as characteristic of it as the cross is for the Christian culture.

This symbol is a severed human head. In all the various forms of its representation in iconography and verbal art one can find the core of the Celtic religion. This is truly, as they say, “a part instead of the whole,” a kind of generalizing symbol of the entire religious philosophy of the pagan Celts.

It happens that it is also the most documented of all cults, fully attested not only by all three of the sources we use here, but also so durable that traces of it survive to this day in the superstitions and folklore of existing Celtic peoples.

The Celts, like many other primitive tribes, hunted heads. We know this from skulls found in Celtic hillforts. In some cases, even the nails with which they were nailed to the gates or pillars around the fortress walls have been preserved. Severed heads were trophies that testified to the military power of the owners, and, at the same time, the powers that were believed to be inherent in the human head served as protection and averted evil from the fortress or home, bringing goodness, luck and success. Diodorus Siculus speaks of the Gauls' custom of beheading their enemies and tells how they nailed the heads to their houses or embalmed them in oil and considered them priceless treasures. His evidence of the importance of the head in Celtic daily and spiritual life is supported by an observation by Livy.

Livy also describes how, in 216, the Boii tribe placed the head of a high-ranking enemy leader in a temple. Human skulls were exhibited in special niches in large temples in Roquepertuse and Entremont, confirming the fair observations of ancient authors. Livy goes on to speak of the Celtic custom of decorating human heads with gold and using them as drinking cups; perhaps this was precisely the function of the human skull discovered in the Libenice sanctuary. There are many examples in the literature of the Celtic peoples of human heads being used in this way. Outright headhunting occurs constantly in the Uladian cycle of Irish tales, as well as in other legends. In The Rape of the Bull of Cualnge, following the first battle after taking up arms, Cú Chulainn returns to Emain Machu with a flock of swans, wild deer, and three severed heads. Later in the “Abduction” it is said that “Cuchulainn held nine heads in one hand and ten in the other and shook them as a sign of his fearlessness and valor” in front of the army. It’s unlikely that the troops asked him any questions about this...

It is said that many characters, gods or heroes, never sat down to feast without placing a severed head on the table before them; The Celts believed that the human head is the seat of the soul, the essence of being. She symbolized the deity itself and possessed all the desired qualities. She could be alive after the death of the body; she could ward off evil and prophesy; she could move, act, speak, sing; she could tell stories and entertain; she presided over the Other World feast. In some cases it was used as a symbol of a particular deity or cult; in others it symbolically expressed religious feelings in general.

The most impressive example from literature regarding the belief in the power of a severed head occurs in the story of Branwen in the Mabinogion. In this tale, which tells of the ill-fated sister of Bran the Blessed, the "Blessed Raven" (possibly originally a powerful Celtic god), the magical severed head of the euhemerized deity plays an important role. It says that Bran was so tall that it was impossible to build a house tall enough to accommodate him, a clear indication of his supernatural nature. After a disastrous expedition to Ireland, he was wounded and, at his request, his surviving comrades cut off his head. Before this, he made prophecies about future events and told them what to do and how to behave in order to avoid troubles and disappointments. Bran's severed head lived on after his body was decapitated. His people took their heads with them to the Other World, where they feasted and had fun for a long time in some magical time, having no idea where they were and not remembering anything about the suffering they endured. The head entertains them and magically provides them with hospitality and company: “And they remained there four to twenty years, but in such a way that they did not notice the time and did not become older than they were when they came there, and there was no more pleasant time for them and fun. And the head was with them, like a living Bendigeid Vran. And therefore their stay there is called the Hospitality of the Honorable Head.”

Finally, one of Bran's friends, ignoring his warnings, opens the forbidden door. The spell breaks and they remember what happened again. Again acting on Bran's orders, they take the head to London and bury it there. She becomes a talisman, warding off evil and plague from the country until she is dug up. After this, her power stops. There are several similar stories in Irish tradition where a severed head presides over celebrations or entertains the crowd.

Archeology fully confirms this most important cult for the pagan Celtic peoples. Hundreds of heads were made from stone; the same number or even more were made of wood, but, of course, much fewer wooden heads have come down to us than stone ones. In La Tène art the human head or mask appears as a constant motif, and here, as in later stone images, a variety of cult attributes can be discerned, including horns, crowns of leaves, or groups of several heads. These heads were undoubtedly endowed with magical powers to ward off evil; some of them depicted individual gods or goddesses.

Rice. 41. Head of Janus from basaltic lava, Leichlingen (Rhineland, Germany).

Rice. 42. Horned head from Starkenburg, Germany.

The Celts firmly believed in the magical power of the number three. According to cult legends, their deities were often born as triplets, along with their two namesakes. Some mythological characters were considered to have three heads. Three-faced heads were depicted in sculpture in Celtic countries in Roman times, undoubtedly also testifying to the sacred power of the number three. Many such heads have been found in Britain. Other heads have the shape of a two-faced Janus (Fig. 41), which perhaps reflects some concept of a god who looks forward to the Other World and back to the human world. Sometimes the heads are crowned with horns; Apparently, this is connected with the cult of horned deities in general (Fig. 42). Sometimes the heads do not have ears, sometimes the ears are exaggerated or the sculptures have slits for inserting animal ears. The eyes are usually emphasized; sometimes one of them is larger than the other, sometimes one or many have several pupils. The faces are usually mask-like and devoid of any expression and have nothing in common with the portrait heads of the ancient world. This huge corpus of heads and the evidence that in ancient times there were many more of them, both wooden and stone, and metal, provide us with an excellent additional source of information about the fundamental, vital role of the human head in the pagan Celtic religion at all times and throughout history. territory of each tribe. It can rightfully be said that the Celts revered a head god - a symbol of their entire religious faith.

Deities and cults

We must now look at the types of deities that the Celts worshiped; for while there is an obvious basic unity of religious belief and ritual practice, there is also a distinct tendency to regard gods and goddesses as divine types within their own distinct cultic sphere. In this case, although we know literally hundreds of deity names from epigraphy and literary tradition (some of them found frequently throughout the Celtic world, others appearing only once or twice), there are only a very limited number of divine types. It is clear that the same type of deity was worshiped over a wide area, even if he or she had different names and their cult legends varied slightly from tribe to tribe and depending on personal preference.

Before proceeding to consider the most prominent of these cults, it is necessary to say something about the Celtic deities as a class. Apparently, the Celts did not have a specific pantheon, a clear division of gods and goddesses according to special functions and categories. There are deities whose frequent appearance in epigraphy and literature suggests perhaps a more profound influence than those who were recorded only once or twice, and this perhaps justifies the assumption of the existence of some hierarchy of deities. However, even in this case we are talking about both gods and goddesses “of all trades”, and about those who were involved in a particular area of public life.

Celtic deities, in general, seem to have been very multifaceted personalities. The tribal god (regardless of what he was called in different areas) was the main type of Celtic deity. Each tribe had its own divine father. He was represented as the ancestor of the people, the father of the king or chief, in whom divine power was believed to reside. Just like this god, the king was responsible for the general well-being of the tribe, the fertility of livestock and the people themselves, for a good harvest and the absence of plague and disasters, for correctly chosen laws and fair judicial decisions. A king "with a vice" or one who turned out to be morally corrupt could only harm the tribe; a good reign ensured good weather and harvest - in a word, everything that was good for people. Like the king, God the Father presided over justice and laws in times of peace. But he could take up arms and lead his men into battle during the war. Caesar writes: “The Gauls all consider themselves descendants of Father Ditus and say that this is the teaching of the Druids.” This Celtic equivalent of Father Dith, the sacred ancestor god, is undoubtedly the same universal tribal god who in the Irish tradition is the Dagda - "The Good God". This is a huge, powerful warrior with a club and a cauldron, the husband of the mighty Morrigan, the raven goddess of war, and also Boand, the eponymous goddess of the Boyne River. Among others, his equivalent in Gaul seems to have been a figure like Sucellus, the “Good Fighter,” who, with his hammer and cup, closely resembles the verbal descriptions of the Dagda.

The god of the tribe became the consort of the earth goddess, whatever her name might be in different places and according to different traditions. As we have already seen, one of the consorts of the Dagda was a powerful goddess of war, who, at her own will, could take the form of a crow or raven and who influenced the outcome of the battle with the help of her magical powers and divinations. Another connection between the two fathers of the tribe - the Gallic Sucellus and the Irish Dagda - is that the companion of the Gallic god was Nantosvelta - “The Maiden of the Winding Stream”, whose attribute was just the raven.

Thus, we can consider that the "basic unit" of the Celtic divine community was the main tribal god, in charge of all aspects of life, the divine counterpart of the king or chief, and his consort - the earth mother, who took care of the fertility of the country, the crops and livestock and who took an active part in the battle against the enemies of the tribe, using not so much weapons as spells and magic spells to win. In addition to the mention of this main divine pair, there is evidence of gods with more limited spheres of influence, which can be found in human society: a blacksmith god, a divine healer, a god who practiced the verbal arts, a patron deity of some sacred well or river. However, the “jack of all trades” god could, if necessary, engage in one of these arts, if necessary, and the spheres of influence of the gods probably overlapped quite often.

Thus it appears that, from the Celtic point of view, the divine social order corresponded to the order in the tribal hierarchy. There is also some evidence of the existence of a group of deities more "high" than the tribal gods, that is, a kind of gods of the gods themselves. Some goddesses appear to have occupied the position of "mother of the gods" at some stage. These are such obscure but powerful figures as Anu, or Danu, Brigid, or Brigantia, or the Welsh Don, who, apparently, filled the same role. Anu is “she who feeds the gods,” perhaps, like Danu, the Welsh Don also corresponds to her. Brigid is a pagan goddess, in some legends she is the mother of the gods Brian, Iukhar and Iukharba. According to other traditions, the mother of these three was Danu; they were called "people of the three gods." However, Brigid's most prominent position was not as the triple daughter of the tribal god Dagda (for there were three sister goddesses named Brigid), but as the early Christian enlightenment saint, Brigid of Kildare. Nine virgins were constantly around the sacred eternal flame of St. Brigid. Its British equivalent was, of course, Brigantia, "High", which gave its name to an area of Roman Britain equal to the modern six northern counties of England and the powerful confederation of the Brigante tribe who lived in that area.

All these powerful female deities, whether they ultimately represent the same goddess or the same basic concept of a divine mother, suggest that above the tribal god and his consort - the earth mother of the tribe - there was indeed a group of higher deities, those who raised the gods themselves and whose sons even surpassed the tribal gods.

Other obscure, vaguely defined, but apparently very interesting goddesses are reflected in literary accounts of female heroines who taught Cuchulain his irresistible techniques in combat and served him so well in times of trouble. Scathach, who is said to have granted (by coercion) the three wishes of Cuchulainn, the hero of the Uladian cycle, was a great warrior-queen in the mold of the ancient Irish divine Queen Medb - "The Intoxicating One". Scathach gives the hero his daughter, first-class training in military strategy, and reveals his future to him. Cu Chulainn then defeats her enemy, another powerful woman, Aife, who rides a chariot herself and ignores the world of men. The Uladian hero defeats him with superior strategy, and she also grants three of his wishes, including not only making peace with Scathach, but also sleeping with Cú Chulainn and giving him a son. This is what happens, but later Cu Chulainn does not recognize the son she bore to him and kills him in a duel before he understands who the young fighter is to him.

It can be believed that all of these powerful warrior goddess-queens are somehow related to each other and they all actually embody the concept of a goddess who is above the tribe - the great goddess of the gods themselves.

Keeping in mind this basis of the organization of the pagan Celtic Otherworld with its division of the gods into the tribal god and mother goddess and then all the gods and goddesses with different, more specific functions, we must now consider some of the individual cults with which these deities were associated, regardless depending on what names they were called under. We have already seen that the cult of the severed human head was vital to Celtic religion and could express all aspects of Celtic religious behavior. Bearing in mind that this symbol alone could represent the many separate cults of which their mythology was composed, we can proceed to a general survey of the more typical cults and the types of deities that were associated with them.

The Celts, as we will see, had a great reverence for animals. It is therefore not surprising that one of the most well-attested types of gods throughout the pagan Celtic world was the horned god. There are two main types of horned god. The first is a god with deer antlers, who, as is known from one inscription, bore the name (K)ernunn - “Horned”. There is early evidence of his cult throughout the Celtic world, and he appears quite regularly. Cernunnos has the antlers of a stag; the god is often accompanied by a deer - his cult animal par excellence. He often wears a torkves, a sacred neck ornament, around his neck, and sometimes holds it in his hands. He is constantly accompanied by a mysterious snake with a ram's head or horns. This creature was also depicted next to the local god, who replaced Mars. The deer god often appears to us sitting on the ground, which apparently recalls the customs of the Gauls, who did not use chairs and sat on the floor.

It is clear that the cult of this god was widespread throughout the Celtic world, and he may have been a deity especially revered by the Druids. There is strong evidence of this deity in the literary traditions of both Wales and Ireland, and the fact that in Christian manuscripts this figure became a symbol of the devil and anti-Christian forces suggests his essential importance to the Celtic religion. He was often depicted as a master of animals. For example, he sits on a cauldron from Gundestrup, holding a snake with the head of a ram by the neck; on his sides stand a wolf and a bear. Many other animals are shown in the background. In contrast to the horned god of the second type, the god with deer antlers is always depicted as peaceful and his entire cult is the cult of fertility and agricultural and commercial prosperity. The dignity and sophistication of this cult speaks of its great antiquity and significance.

The second type of horned god, which we also find throughout the Celtic world, is the god with the horns of a bull or ram. He is infinitely rougher than his brother with deer antlers, but they also have something in common. At times these two cults seemed to merge into one. For example, both gods were associated with the Roman Mercury. Mercury's association with economic prosperity must have led to the identification of the Celtic deity with antlers with this ancient god. Moreover, in his more ancient role as protector of flocks, Mercury naturally resembled in many ways the stag-horned deity (as ruler of animals) and the bull-horned or ram-horned god, who was also clearly associated with shepherding. The name of the god with bull horns is unknown. He may have been one of those deities worshiped in parts of Gaul or Roman Britain, where the evidence for his cult is particularly impressive. In many ways he is the god of war. Sometimes in local iconography it appears as the horned head of the most typical local species. Most often he was depicted as a naked warrior with a clearly drawn phallus, holding a spear and shield in his hands. Sometimes it is compared to Mars, and sometimes to Mercury. In addition, he, as a rough forest deity, could be identified with Silvanus - a god also phallic, but at the same time unarmed. As the god of constantly warring shepherd tribes, he vividly reflected their attitude to life and cherished aspirations - a mighty warrior, protector of herds, who gave courage and fertility to people and animals.

We have already seen that the tribal god was essentially a powerful warrior, and, regardless of what were his spheres of influence and activities in times of peace, when the tribe was in danger of invasion or was ready to go on a campaign to conquer new lands, the god -the father became his leader in battle, the divine ideal of human courage and endurance. The Celts, a restless, mobile people, preferred beautiful decorations to permanent houses, complex and durable religious buildings, and therefore had to have some kind of amulets or idols that were easy to carry and that would serve as a symbol of the divine warrior or would be dedicated to him. Often it was apparently a head made of stone or wood, or a small wooden idol, or maybe even just a stone or a sacred weapon in which the god spoke, inspiring the warriors.

It was natural that to the Romans, when they first became acquainted with the Celts, the Celtic deities should have seemed monstrously aggressive, and so the tribal god of the Celts tended to be identified with Mars, the Roman god of war. As conflict and tension subsided and life became more peaceful and tranquil under Roman rule, the tribal god continued to be depicted as Mars. However, we know that in many cases, mainly taking into account other attributes and dedications to this god that we find in the iconography, the warrior god was associated more with phenomena such as healing waters and agricultural fertility, or figured in the role of a local god -protector, custodian of local cultural tradition.

In the northern regions of Britain, where the Roman conquest never lost its military aspect, the warrior god - most often with the horns of a bull or ram - was depicted as Mars, and only in his guise as the god of war. Only one northern deity, namely Mars Condatis - "Mars at the meeting of the waters", who was worshiped at Chester-le-Street and Pearsebridge in County Durham, suggests the powers of a sacred spring or river, recalling the role of Mars in many areas of Gaul and southwest England. The gods identified with Mars in the south-eastern regions of Britain were primarily associated with healing. It is interesting that Irish deities were also involved in healing. Lugh, the son of Ethlenn from the Tribes of the Goddess Danu in the ancient Irish tradition, an unusually skillful warrior who, in addition, owned many different crafts, was allegedly the divine father of the great hero Cuchulainn. When Cuchulainn was almost mortally wounded ("The Rape of the Bull of Cualnge"), Lugh comes to him in the guise of a warrior; at the same time, however, no one sees him except the hero himself. He sings magic spells over his son to induce sleep on him, and then applies sacred herbs and plants to his terrible wounds and heals the wounded hero with chants: Cuchulainn is again whole, unharmed and ready to fight.

For such a warlike people as the Celts, God in his warrior form had to occupy a leading place in mythology and later iconography. We should not forget about the cult of weapons. As we have already seen, many ancient Irish sagas tell that some especially revered swords, shields or spears were made by the gods themselves or acquired by the gods and brought to Ireland by them.

In general, Celtic goddesses were powerful female deities. They were mainly in charge of the earth, the fertility of both plants and animals, sexual pleasures, as well as war in its magical aspect. The concept of a trinity of female deities appears to have played a fundamental role in pagan Celtic beliefs. In iconography, the tribal mother goddess was depicted primarily as a group of three mother goddesses known in both the Gallo-Roman and Romano-British worlds. The maternal aspect of the tribal goddess was of paramount importance; therefore, it is not surprising that in sculpture she was depicted as a mother goddess who feeds her child, holds him in her lap or plays with him. The maternal and sexual aspects of the Celtic goddesses are quite well attested. However, in addition to this basic function of the tribal mother goddess, other, narrower spheres of influence of female deities can be identified. For example, the warlike triple raven goddess, or rather, three goddesses named Morrigan, were more concerned with battle as such, prophesying and changing their appearance, although their sexual aspect is also very clearly expressed. Other goddesses, such as Flidas, seem to have been, like Cernunnos and other deities, the mistress of the forest animals - the Celtic equivalent of Diana. They hunted, raced their chariots through wild thickets, and also protected herds and contributed to their increase. Flidas was the lover of the great hero Fergus, son of Roach ("Great Horse"). Only she could satisfy him completely sexually.

Among other goddesses who are known to us from the ancient Irish tradition, we can name Medb herself with her endless series of husbands and lovers; great goddesses of healing springs and wells; obscure female deities, such as the British goddess Ratis - “goddess of the fortress”, Latis - “goddess of the pond” (or beer) and so on. Another deity we don't know much about is Coventina, the nymph goddess of northern Britain. Many dedications to her have survived, and she had her own cult center at Carrowburgh (Brocolithia) on Hadrian's Wall in Northumberland. The richness and complexity of the votive offerings in the sacred wells of Coventina speak of the veneration in which it was surrounded. Traces of her name on the continent suggest that the area of her cult was wider than it appears at first glance.

At Bath, Somerset (anciently Aqua Sulis), the Romans adapted to their needs the cult of another great local goddess of the springs. The goddess of the hot springs of Bath - Sulis - was identified with the ancient Minerva. The iconography of Roman goddesses shows an image that is both ancient and native; it sometimes seems that the ancient images appeared primarily to give a tangible image to the local beliefs through which the source was dedicated to Sulis in the first place. In addition, at Aqua Arnemedia (Buxton) in Derbyshire, a Roman goddess was also venerated at sacred springs in Roman times.

Consequently, the major Celtic goddesses throughout the pagan Celtic world were mother goddesses and performed corresponding maternal and sexual functions. There were also war goddesses who sometimes wielded weapons and sometimes used the power of magic to grant success to the side they supported. The hero Cu Chulainn, having rejected the sexual advances of the great Morrigan, immediately experiences her resentment and anger. In a gloomy, vindictive mood, she comes to Cuchulainn precisely at the moment when he is having a hard time in a duel: “Morrigan appeared to them in the guise of a white red-eared heifer, leading fifty more heifers, chained in pairs with chains of light bronze. Here the women imposed bans and gesses on Cuchulainn, so that he would not let Morrigan leave without harassing and destroying her. From the very first throw, Morrigan's eye struck Cuchulain. Then she swam downstream and wrapped herself around Cuchulainn’s legs. While he was struggling to free himself, Loch inflicted a wound on him across the throat. Then Morrigan appeared in the guise of a shaggy red she-wolf, and again wounded Cuchulain Loch while he drove her away. Cuchulainn was filled with anger and struck the enemy’s heart in the chest with a blow from the ha bulga.”

Thus, the Celtic goddesses had dominion over the earth and the seasons; they were full of sexual energy and radiated maternal kindness. Many of them have clearly passed into folk tradition, such as the Irish Crone of Barra, the Scottish Crone of Benn Brick, or the strange sea-related Mulidartach; they perform miracles, and their spheres of influence correspond closely to those seen in the iconography and textual traditions of the older, pagan world.

Birds played a vital, fundamental role in the imagery of the pagan Celtic religion. Human emotions towards birds must obviously be considered very ancient, and one can clearly determine how people felt about individual species (Fig. 43). It is remarkable that some birds have been treated with reverence throughout the ages, and these ideas have passed into modern oral tradition. Others experienced a short period of popularity, but birds - both in general and individual species - have always resonated with the Celtic character.