Charles I is the king of England, Scotland and Ireland. Charles I - life and execution The first war of Charles 1 with parliament

This term has other meanings, see Charles II. Charles II Charles II ... Wikipedia

King of England and Scotland from the Stuart dynasty, who reigned from 1625 to 1648. Son of James 1 and Anne of Denmark. J.: from June 12, 1625 Henrietta Maria, daughter of King Henry IV of France (b. 1609, d. 1669). Genus. November 29, 1600, d. 30 Jan 1649… … All the monarchs of the world

King of England and Scotland from the Stuart dynasty, who reigned from 1660 to 1685. Son of Charles I and Henrietta of France. J.: from 1662 Catherine, daughter of King John IV of Portugal (b. 1638, d. 1705). Genus. 29 May 1630, d. 16 Feb 1685 In the very… All the monarchs of the world

Charles I of Anjou Charles I d Anjou Statue of Charles of Anjou on the facade of the royal palace in Naples ... Wikipedia

King of Spain from the Bourbon dynasty, who reigned from 1788 to 1808. J.: from 1765 Maria Louise, daughter of Duke Philip of Parma (b. 1751, d. 1819) b. November 11, 1748, d. 19 Jan 1819 Before ascending the throne, Charles lived completely idle... All the monarchs of the world

Wikipedia has articles about other people named Carl. Charles VI the Mad Charles VI le Fol, ou le Bien Aimé ... Wikipedia

This term has other meanings, see Charles II. Charles II Carlos II ... Wikipedia

This term has other meanings, see Charles IV. Charles IV Carlos IV ... Wikipedia

Charles II the Evil Charles II de Navarre, Charles le Mauvais ... Wikipedia

Charles V (Charles I) Karl V., Carlos I Portrait of Charles V in the chair by Titian Emperor ... Wikipedia

Books

- Works, Karl Marx. PREFACE TO THE FIRST VOLUME The first volume of the Works of K. Marx and F. Engels contains works written by them in 1839-1844, before the beginning of the creative collaboration of the founders of the scientific…

- Collection Monarchs, Vinnichenko Tatyana, Butakova Elena, Dubinyansky Mikhail. The collection "Monarchs" includes twelve biographical essays, the heroes of which are: the King of the Franks Charlemagne, the Queen of England and France Eleanor of Aquitaine, the founder of the Timurid Empire...

On a cold January morning in 1649, it was not an ordinary criminal who climbed onto the scaffold in the center of London, but a king who had ruled his people for twenty-four years. On this day, the country completed the next stage of its history, and the finale was the execution of Charles 1. In England, the date of this event is not marked in the calendar, but it forever entered its history.

Scion of the noble Stuart family

The Stuarts were a dynasty descended from an ancient Scottish house. Its representatives, having more than once occupied the English and Scottish thrones, left a mark on the history of the state like no one else. Their rise dates back to the early 14th century, when Earl Walter Stewart married the daughter of King Robert I the Bruce. It is unlikely that this marriage was preceded by a romantic story; most likely, the English monarch considered it beneficial to strengthen his connection with the Scottish aristocracy with this union.

Charles the First, whose tragic fate will be discussed in this article, was one of the descendants of the venerable Count Walter, and like him, belonged to the Stuart dynasty. With his birth, he “made happy” his future subjects on November 19, being born in the ancient residence of the Scottish monarchs - Denfermline Palace.

For his subsequent accession to the throne, little Charles had an impeccable origin - his father was King James VI of Scotland, and his mother was Queen Anne of Denmark of England. However, the matter was spoiled by Henry's elder brother, the Prince of Wales, who was born six years earlier and therefore had a priority right to the crown.

In general, fate was not particularly generous to Charles, of course, if this can be said about a youth from the royal family. As a child, he was a sickly child, somewhat delayed in development, and therefore later than his peers began to walk and talk. Even when his father inherited the English throne in 1603 and moved to London, Charles could not follow him, as the court physicians feared that he would not survive the journey.

It should be noted that physical weakness and thinness accompanied him all his life. Even in ceremonial portraits, artists were unable to give this monarch any kind of majestic appearance. And Charles 1 Stuart was only 162 cm tall.

The path to the royal throne

An event occurred that determined Karl’s entire future fate. That year, a terrible typhus epidemic broke out in London, from which it was impossible to hide even within the walls of the royal castle. Fortunately, he himself was not injured, since he was in Scotland at that time, but the victim of the disease was his older brother Henry, who was prepared from birth to rule the country, and on whom all high society had high hopes.

This death opened the way for Charles to power, and as soon as the funeral ceremonies were completed in Westminster Abbey, where Henry’s ashes rested, he was elevated to the rank of Prince of Wales - heir to the throne, and over the next years his life was filled with all sorts of preparations for the fulfillment of such a high mission.

When Karl turned twenty, his father became concerned about the arrangement of his future family life, since the marriage of the heir to the throne is a purely political matter, and Hymen is not allowed to shoot at him. James VI chose the Spanish infanta Anna. This decision caused indignation among members of parliament who did not want a dynastic rapprochement with the Catholic state. Looking ahead, it should be noted that the future execution of Charles 1 will have a largely religious background, and such a rash choice of a bride was the first step towards it.

However, at that moment there were no signs of trouble, and Karl went to Madrid with the desire to personally intervene in the marriage negotiations, and at the same time to look at the bride. On the trip, the groom was accompanied by his favorite, or rather, his father’s lover, George Villiers. According to historians, VI had a large and loving heart, which accommodated not only the ladies of the court, but also their honorable husbands.

Unfortunately, the negotiations in Madrid reached a dead end, since the Spanish side demanded that the prince accept Catholicism, and this was completely unacceptable. Charles and his new friend George were so wounded by the obstinacy of the Spaniards that upon returning home they demanded that Parliament break relations with their royal court, and even disembark an expeditionary force to conduct military operations. It is not known how it would have ended, but, fortunately, at that moment a more accommodating bride turned up - the daughter of Henry IV, Henrietta Maria, who became his wife, and the rejected groom calmed down.

At the pinnacle of power

Charles 1 Stuart ascended the throne after the death of his father in 1625, and from the very first days began to conflict with Parliament, demanding subsidies from it for all sorts of military adventures. Not getting what he wanted (the economy was bursting at the seams), he dissolved it twice, but each time was forced to reconvene it. As a result, the king obtained the necessary funds by imposing illegal and very burdensome taxes on the population of the country. History knows many similar examples when short-sighted monarchs plugged budget holes by tightening taxes.

Subsequent years also brought no improvement. His friend and favorite George Villiers, who after the death of James VI finally moved to Charles’s chambers, was soon killed. This scoundrel turned out to be dishonest, and he paid for it while collecting taxes. Having not the slightest idea of economics, the king always considered new and new levies, fines, the introduction of various monopolies and similar measures to be the only way to replenish the treasury. The execution of Charles 1, which followed in the twenty-fourth year of his reign, was a worthy finale to such a policy.

Soon after the murder of Villiers, a certain Thomas Wentworth stood out noticeably from the circle of courtiers, who managed to make a brilliant career during the reign of Charles the First. He came up with the idea of establishing absolute royal power in the state, based on a regular army. Having subsequently become viceroy in Ireland, he successfully implemented this plan, suppressing dissent with fire and sword.

Reforms that caused social tension in Scotland

Charles the First did not show foresight in the religious conflicts that tore the country apart. The fact is that the majority consisted of followers of the Presbyterian and Puritan churches, belonging to two of the many directions of Protestantism.

This often served as a reason for conflicts with representatives of the Anglican Church, which dominated England and was supported by the government. Not wanting to seek a compromise, the king tried to establish her dominance everywhere by violent measures, which caused extreme indignation among the Scots, and ultimately led to bloodshed.

However, the main mistake, which resulted in the civil war in England, the execution of Charles 1 and the subsequent political crisis, should be considered his extremely ill-conceived and ineptly pursued policy towards Scotland. Most researchers of such a sadly ended reign unanimously agree on this.

The main direction of his activity was the strengthening of unlimited royal and church power. This policy was fraught with extremely negative consequences. In Scotland, for a long time, traditions have developed that consolidated the rights of estates and elevated the inviolability of private property into law, and it was these that the monarch encroached on in the first place.

The short-sightedness of royal policy

In addition, it should be noted that the biography of Charles 1 was tragic not so much because of the goals he pursued, but because of the ways of their implementation. His actions, usually overly straightforward and poorly thought out, invariably caused popular indignation and contributed to strengthening the opposition.

In 1625, the king alienated the vast majority of the Scottish nobility by issuing a decree that went down in history as the “Act of Revocation.” According to this document, all decrees of the English kings, starting in 1540, on the transfer of land plots to the nobility were annulled. To preserve them, the owners were required to contribute to the treasury an amount equal to the value of the land.

In addition, the same decree ordered the return to the Anglican Church of its lands located in Scotland and confiscated from it during the Reformation, which established Protestantism in the country, which fundamentally affected the religious interests of the population. It is not surprising that after the publication of such a provocative document, many protest petitions were submitted to the king from representatives of various sectors of society. However, he not only pointedly refused to consider them, but also aggravated the situation by introducing new taxes.

Nomination of the episcopate and abolition of the Scottish Parliament

From the first days of his reign, Charles I began to nominate Anglican bishops to the highest government posts. They were also given the majority of seats in the royal council, which significantly reduced the representation of the Scottish nobility in it and gave a new reason for discontent. As a result, the Scottish aristocracy found itself removed from power and deprived of access to the king.

Fearing the strengthening of the opposition, the king practically suspended the activities of the Scottish Parliament from 1626, and by all means prevented the convening of the General Assembly of the Scottish Church, into whose worship, by his order, a number of Anglican canons alien to them were introduced. This was a fatal mistake, and the execution of Charles 1, which became the sad end of his reign, was the inevitable consequence of such miscalculations.

Beginning of the first civil war

When there was talk of infringement of the political rights of the nobility, such actions caused protest only in their narrow class circle, but in the case of violation of religious norms, the king set the whole people against himself. This again caused a stream of outrage and protest petitions. As before, the king refused to consider them, and added fuel to the fire by executing one of the most active petitioners, charging him with the usual charge of treason in such cases.

The spark that exploded Scotland's powder magazine was the attempt to hold a service based on the Anglican liturgy in Edinburgh on July 23, 1637. This caused not only the indignation of citizens, but also an open revolt that engulfed most of the country, and went down in history as the First Civil War. The situation was heating up every day. The leaders of the noble opposition drew up and sent to the king a protest against the church reform alien to the people, and the widespread rise of the Anglican episcopate.

The king's attempt to defuse the situation by forcibly removing the most active oppositionists from Edinburgh only worsened general discontent. As a result, under pressure from his opponents, Charles I was forced to make concessions, removing bishops hated by the people from the royal council.

The result of general unrest was the convening of the National Convention of Scotland, consisting of delegates from all social strata of society, and headed by representatives of the highest aristocracy. Its participants drew up and signed a manifesto on joint actions of the entire Scottish nation against attempts to make any changes to their religious foundations. A copy of the document was handed to the king, and he was forced to reconcile. However, this was only a temporary lull, and the lesson taught to the monarch by his subjects was of no use. Therefore, the execution of Charles 1st Stuart was the logical conclusion of the chain of his mistakes.

New civil war

This arrogant, but very unlucky ruler also disgraced himself in another part of the kingdom subordinate to him - Ireland. There, for a certain and very substantial bribe, he promised patronage to local Catholics, however, having received money from them, he immediately forgot about everything. Offended by this attitude towards themselves, the Irish took up arms in order to use it to refresh the memory of the king. Despite the fact that by this time Charles I had completely lost the support of his own parliament, and with it the bulk of the population, he tried, with a small number of regiments loyal to him, to change the current situation by force. So, on August 23, 1642, the Second Civil War began in England.

It should be noted that Charles I was as incompetent as a commander as he was as a ruler. If at the beginning of hostilities he managed to win several fairly easy victories, then on July 14, 1645, his army was completely defeated in the Battle of Nesby. Not only was the king captured by his own subjects, but also an archive containing a lot of incriminating evidence was captured in his camp. As a result, many of his political and financial machinations, as well as requests for military assistance from foreign countries, became public.

Crowned Prisoner

Until 1647, Charles I was kept in Scotland as a prisoner. However, even in this unenviable role, he continued to make attempts to come to an agreement with representatives of various political groups and religious movements, generously handing out promises left and right that no one believed. In the end, the jailers extracted the only possible benefit from him by transferring (selling) him to the English Parliament for four hundred thousand pounds sterling. The Stuarts are a dynasty that has seen a lot in its lifetime, but it has never experienced such shame.

Once in London, the deposed king was placed in Golmby Castle, and then transferred to Hampton Court Palace, under house arrest. There, Charles had a real opportunity to return to power, having accepted the offer that was approached by a prominent politician of that era for whom the execution of Charles 1, which had become quite real by that time, was unprofitable.

The conditions offered to the king did not contain any serious restrictions on the royal powers, but even here he missed his chance. Wanting even greater concessions, and having started secret negotiations with various political groups in the country, Charles avoided a direct answer to Cromwell, as a result of which he lost patience and abandoned his plan. Thus, the execution of Charles 1 Stuart was only a matter of time.

The tragic outcome was accelerated by his escape to the Isle of Wight, located in the English Channel, not far from the British coast. However, this adventure also ended in failure, as a result of which house arrest in the palace was replaced by imprisonment in a prison cell. From there, Baron Arthur Capel, whom Charles had once made a peer and elevated to the very top of the court hierarchy, tried to rescue his former monarch. But, not having sufficient strength, he soon found himself behind bars.

Trial and execution of the deposed king

There is no doubt that the most characteristic feature of this scion of the Stuart family was the tendency to intrigue, which as a result destroyed him. For example, while making vague promises to Cromwell, he simultaneously conducted behind-the-scenes negotiations with his opponents from parliament, and receiving money from Catholics, he also supported Anglican bishops with it. And the execution of King Charles 1 itself was largely accelerated due to the fact that, even while under arrest, he did not stop sending out calls for rebellion everywhere, which in his position was complete madness.

As a result, most of the regiments submitted a petition to Parliament demanding a trial of the former king. The year was 1649, and the hopes with which British society had greeted his accession to the throne were long gone. Instead of a wise and far-sighted politician, it received a proud and limited adventurer.

To conduct the trial of Charles I, Parliament appointed one hundred and thirty-five commissioners, headed by the prominent lawyer of the time, John Bradshaw. The execution of King Charles 1 was predetermined in advance, and therefore the whole procedure did not take much time. The former monarch, a man who only yesterday commanded a mighty power, was unanimously recognized as a tyrant, a traitor and an enemy of the fatherland. It is clear that the only possible sentence for such serious crimes could be death.

The execution of the English king Charles 1 took place in the early morning of January 30, 1649 in London. We must give him his due - even after ascending the scaffold, he retained his presence of mind and addressed the assembled crowd with his dying speech. In it, the convict stated that civil liberties and freedoms are ensured solely by the presence of a government and laws that guarantee citizens life and the inviolability of property. But at the same time, this in no way gives the people the right to claim control of the country. The monarch and the crowd, according to him, are completely different concepts.

Thus, even on the verge of death, Charles defended the principles of absolutism, of which all the Stuarts were adherents. England still had a long way to go before the constitutional monarchy was fully established, and the people, contrary to their opinion, had the opportunity to participate in government. However, the foundation for this had already been laid.

According to the memoirs of contemporaries, the execution of the English king Charles 1 gathered a huge crowd of people who were in a state close to shock throughout this bloody performance. The climax came when the executioner lifted the severed head of their former sovereign by the hair. However, the traditional words in such cases that it belongs to a state criminal and traitor were not heard.

So, 1649 put a bloody end to the reign of this king. However, another eleven years will pass, and a period will begin in the history of England called the Stuart Restoration, when representatives of this ancient family will once again ascend the throne. The Second Civil War and the execution of Charles 1 were its threshold.

Charles I (1600-1649), English king (from 1625) from the Stuart dynasty.

Like his father, Charles was a staunch supporter of absolute monarchy. He viewed parliament only as an auxiliary instrument of the state machine. This caused extreme wariness in the House of Commons, which had the power to finance the crown.

Requests submitted by Charles to Parliament for subsidies necessary to wage war with Spain and France remained unanswered. The parliamentarians were also irritated by the first minister, the Duke of Buckingham, who actually ruled the country (he was killed in 1628). After his death, Charles, taking the reins of power into his own hands, made peace with external enemies.

The king was a supporter of strengthening the power of bishops in the Church of England, which was considered by the Puritans (orthodox Protestants) as papism. Married to a Catholic, the French princess Henrietta, Charles actually advocated a softening of attitudes towards Catholics in England. Such tolerance angered the Puritans, who gradually won a majority in the House of Commons. Charles dissolved parliament four times, pursuing a tough tax policy between sessions. On the other hand, wanting to achieve subsidies, he convened Parliament again and again, making concessions unprecedented in English history. The most significant of them was the approval of the “Petition of Right” (1628), which guaranteed the inviolability of the person.

In 1639, an attempt to install Anglican bishops over the Scottish Puritans caused a rebellion. The king, having suffered defeat in the war with the Scots, was again forced to resort to the help of parliament. The so-called Long Parliament, which met in London in 1640, relying on the support of the townspeople, made Charles completely dependent on himself. The king made more and more concessions. At the request of Parliament, he even sent Strafford, his closest associate and personal friend, to the scaffold. Meanwhile, parliament put forward further demands concerning the limitation of royal power and the abolition of episcopacy. The situation was aggravated by the uprising of Catholics in Ireland - the Puritans accused Charles of involvement in the rebellion.

In 1642, the king tried to seize the initiative and arrest the Puritan leaders. When the attempt failed, he left London and began army recruitment. Civil war broke out in England. At first, success was on Charles’s side, but in 1645, in the battle of Nezby, his troops were defeated. In 1646, the king surrendered to the Scots, who handed him over to parliament for 400 thousand pounds. After this, Karl finally turned into a prisoner and toy of the warring parliamentary parties.

The Independents (orthodox Puritans) led by O. Cromwell captured the king in 1647, using him to blackmail the parliamentary majority. After Cromwell's army entered London, Charles managed to escape to the Isle of Wight. From here he tried to achieve the unification of his supporters with the Presbyterians (moderate Puritans). But these plans fell through.

The Second Civil War ended with Cromwell's victory. Karl found himself in his hands. In 1649, parliament (more precisely, independent deputies of the House of Commons without the consent of the House of Lords) sentenced the king to death on charges of “high treason.”

A. Van Dyck. Portrait of Charles I of England. Louvre. Paris.

Charles I (1600-1649) - English king since 1625, from the Stuart dynasty. He was recognized as the main culprit of the Civil War. On January 30, 1649, in the presence of a large crowd, the monarch was beheaded, and in England a republic was established.

Charles I (19.XI.1600 - 30.I.1649) - king (1625-1649) from the Stuart dynasty. Son James I. He pursued a reactionary feudal-absolutist policy that contradicted the interests of the bourgeoisie and the “new nobility.” Dissolved opposition parliaments (in 1625, 1626, 1629). He surrounded himself with reactionary advisers (Archbishop W. Laud, Lord Strafford, etc.). The policy of feudal reaction especially intensified during the period of the unparliamentary reign of Charles I (1629-1640). High taxes, arbitrary exactions (“ship tax”, 1635), arrests of opposition leaders of parliament, persons who refused to pay taxes, and bloody repressions against the Puritans aroused enormous discontent in the country. This was also facilitated by the personal qualities of Charles I - frivolous, self-confident and narrow-minded. The lack of sufficient financial resources (in particular, to wage war in Scotland, where an anti-English uprising began in 1637) forced Charles I to convene in April 1640 parliament, which he dissolved on May 5, 1640 (the so-called Short Parliament). The convening in November 1640, in conditions of a revolutionary situation in the country, of a new parliament (referred to as the Long) was the beginning of the English bourgeois revolution. In the civil wars of 1642-1646 and 1648, Charles I was defeated. On January 26, 1649, by the Supreme Judicial Tribunal, created by Parliament specifically to try the king, under pressure from the popular masses, Charles I, “as a tyrant, traitor, murderer and enemy of the state,” was sentenced to death and beheaded on January 30.

Soviet historical encyclopedia. In 16 volumes. - M.: Soviet Encyclopedia. 1973-1982. Volume 7. KARAKEEV - KOSHAKER. 1965.

Charles I - King of England and Scotland from the Stuart dynasty, who ruled in 1625- 1648 gg. Son of James I and Anne of Denmark.

Wife: from June 12, 1625 Henrietta Maria, daughter of King Henry IV of France (b. 1609 + 1669).

Charles was the third son of King James I and became heir only in 1616, after the death of his two older brothers. As a child, he was a meek and submissive child, and in his youth he was distinguished by his diligence and penchant for theological debates. But then the prince became close friends with his father's favorite Duke of Buckingham, who had a very bad influence on him. In the last years of his reign, King James I hatched plans for an alliance with Spain and wanted to marry his son to a Spanish princess. The Duke of Buckingham convinced Charles to follow his bride to Madrid as a wandering lover. This romantic adventure captivated Karl so much that even his father’s insistent arguments did not force him to abandon this idea. Karl and Buckingham arrived in Madrid in disguise, but here their appearance aroused more surprise than joy. Long negotiations came to nothing, and Charles returned to England a convinced enemy of Spain. Soon Jacob died, and Charles ascended to the English throne. The new king lacked neither courage nor military skill. With the virtues of the father of the family, he combined some of the virtues of the head of state. However, his rude and arrogant manner cooled affection and repelled devotion. Most of all, Karl was let down by his inability to choose the right tone: he showed weakness in those cases when it was necessary to resist, and stubbornness when it was necessary to yield. He could never understand either the character of the people with whom he had to fight, or the main aspirations of the people he had to govern.

At his first parliament in 1625, Charles demanded subsidies for the war with Spain in terse terms and in an imperative tone. Deputies agreed to allocate 140 thousand pounds sterling for military needs and approved a “barrel tax” for this purpose, but only for one year. The angry king dissolved the chambers. The Parliament of 1626 began its sessions with an attempt to install the royal favorite, the Duke of Buckingham, in court. Charles went to the House of Lords and announced that he accepted responsibility for all the orders of his minister. He again dissolved parliament, and in order to get money, he had to resort to a forced loan, which caused general indignation. With great difficulty and violation of laws, only insignificant funds were obtained, which were then spent without any benefit on the war with France. In 1628 Charles convened his third parliament. Its members were elected in a moment of general irritation and indignation. Skirmishes between the deputies and the king began again. The Magna Carta, which was not remembered during the entire reign of the Tudors, was brought out of oblivion. Based on it, the House of Commons drew up the “Petition of Rights,” which was, in essence, a statement of the English Constitution. After much hesitation, Karl approved it. From that time on, the “petition” became the basic English law, and was constantly appealed to in clashes with the king. Charles, who agreed to such an important concession, did not gain anything in return, since Parliament did not agree to approve the subsidies and again demanded that Buckingham be brought to court. Fortunately for the king, the hated duke was killed in 1629 by the fanatic Felton. Charles dissolved parliament and ruled without it for the next eleven years.

Charles owed such a long period of absolute rule to the fact that he had a skillful treasurer in the person of Weston, an energetic assistant in religious affairs in the person of Archbishop Laud, and, especially, such a talented statesman as Lord Strafford. The latter, ruling Northern England and Ireland, was able, thanks to various abuses, to annually collect significant subsidies from the population, sufficient to maintain an army of five thousand. Archbishop Laud, meanwhile, began severe persecution of the Puritans and forced many of them to emigrate to America. Seeking funds, the king introduced new taxes with his authority. Thus, in 1634, a “ship duty” was introduced. But collecting these taxes became more and more difficult every year. The government had to initiate legal proceedings against malicious tax evaders, which caused loud murmurs of public indignation. Pamphlets directed against the king began to appear in large quantities. The police searched for their authors and punished them. This in turn gave rise to new indignation. In Scotland, where the Puritan position was much stronger than in England, the king's policies led to a powerful uprising in 1638. Leslie's army of twenty thousand invaded England from Scotland. Charles did not have the strength to fight her, and in 1640 he had to convene the fourth parliament.

The king hoped that, under the influence of patriotism, the deputies would allow him to raise the funds necessary to wage the war. But he was wrong once again. At the very first meeting of the House of Commons, the deputies announced their intention to review everything that had been done without their participation over these eleven years. The king declared parliament dissolved, but he was in a very difficult position: his army consisted of all sorts of rabble and was constantly defeated in the war. In November 1640, he unwillingly convened a new parliament, which went down in history under the name of the Long. On November 2, deputies demanded a trial of Strafford. On the same day he was arrested and, together with Laud, imprisoned. Everyone who took any part in collecting the “ship duty” was persecuted. Without any military force in its hands and relying only on the London crowd, Parliament actually seized government control into its own hands. Karl made one concession after another. In the end, he sacrificed his minister, and in May 1641, the hated Strafford was beheaded. Soon parliament abolished all tribunals that did not obey the general rules, including the Star Chamber. Laws were passed stating that the interval between the dissolution of the previous parliament and the convening of a new one could not exceed three years and that the king could not dissolve parliament against his will.

Karl defended himself as best he could. In January 1642, he accused five members of the House of Commons of secret relations with the Scots and demanded their arrest. He himself went to Westminster, accompanied by nobles and bodyguards, to capture the suspects, but they managed to flee to the City. Karl, annoyed, hurried after them, but was never able to take the troublemakers into custody. The sheriffs refused to carry out his order, and a violent crowd, running from all sides, greeted the king with loud cries of “Privilege! Privilege!" Karl saw his powerlessness and left London that same day. Five members of the House of Commons solemnly returned to Westminster under the protection of the city police.

The king settled in York and began to prepare for a campaign against the capital. All attempts to peacefully resolve the conflict ended in failure, as both sides showed intransigence. Parliament demanded for itself the right to appoint and dismiss ministers and sought to subordinate all branches of government to its control. Charles replied: “If I agree to such conditions, I will become only a ghostly king.” Both sides were gathering troops. Parliament introduced taxes and formed an army of 20 thousand. At the same time, the king's supporters flocked to the northern counties. The first battle, which took place in October at Edgegill, did not have a decisive outcome. But soon uprisings began in the western counties in favor of the king. The city of Bristol surrendered to the Royalists. Having firmly established himself in Oxford, Charles began to threaten London, but resistance to him grew with each passing month. Since all the bishops took the side of the king, parliament in 1643 announced the abolition of bishoprics and the introduction of Presbyterianism. Since then, nothing has prevented a close rapprochement with the rebel Scots. In 1644, the king had to simultaneously wage war against the army of Parliament and the army of Leslie. On July 3 the royalists were defeated at Merston Moor. The squad played a decisive role in this victory Oliver Cromwell composed of fanatical Puritans. The northern counties recognized the authority of Parliament. For some time, Charles continued to win victories in the south. Throughout this war, he showed, along with his usual fearlessness, composure, energy and outstanding military talents. The Parliamentary army under Essex was surrounded and capitulated in Cornwall on 1 September. This defeat led to the fact that the Independents (extreme Puritans) led by Cromwell took over in the House of Commons. The people in the capital were overwhelmed with religious enthusiasm. The Independents banned all entertainment; time was divided between prayer and military exercises. In a short time, Cromwell formed a new army, distinguished by extremely high fighting spirit. On 14 June 1645 she met the royalists at Naseby and inflicted a decisive defeat on them. The king retreated, leaving five thousand dead and one hundred banners on the battlefield. In the following months, parliament extended its influence throughout the country.

Accompanied by only two people, Charles fled to Scotland, wanting to get support from his fellow countrymen. But he miscalculated. The Scots captured the king and handed him over to parliament for 800 thousand pounds sterling. Karl found himself a prisoner in Golmeby. True, even now his situation was far from hopeless. The House of Commons offered him peace on the condition that he agree to the destruction of the episcopal structure of the church and submit the army to the subordination of parliament for twenty years. Soon a third force intervened in these negotiations. During the war years, the army turned into an independent and powerful organization with its own interests and was not always ready to carry out the instructions of parliament. In June 1647, several squadrons captured the king at Golmsby and took him under escort to their camp. Here negotiations began between the king and the army commanders. The conditions proposed by these latter were less restrictive than parliamentary ones. Thus, the period for which the king had to give up command of the army was reduced to ten years. Karl hesitated to make a final decision - he hoped that he could still be the winner; on November 11, he fled from Hampton Court to the Isle of Wight. Here, however, he was immediately captured by Colonel Grommond and imprisoned in Kerisbroke Castle. However, the king's flight served as a signal for a second civil war. Violent royalist revolts broke out in the southeast and west of the country. The Scots, to whom Charles had promised to preserve their Presbyterian Church, agreed to support him. But even after this, the king had no hope of victory. Cromwell defeated the Scots and, pursuing them, entered Edinburgh. The rebellious Colchester capitulated to Fairfax's army.

In July 1648, new negotiations began. Charles accepted all the demands of the victors, except for the abolition of episcopacy. Parliament was ready to make peace on these terms, but the army, imbued with the Puritan spirit, fiercely opposed this concession. On December 6, a detachment of soldiers under the command of Colonel Pride expelled 40 deputies from the House of Commons who were inclined to compromise with the king. The next day, the same number were expelled. Thus, independents, acting in concert with the army, received a majority in parliament. In reality, this coup marked the beginning of Cromwell's sole rule. He entered the capital as a triumphant man and took up residence in the royal rooms of Guategall Palace as sovereign of the state. Now, on his initiative, parliament decided to put the king on trial as a rebel who had started a war with his own people. Charles was taken under guard to Windsor and then to St. James's Palace. At the beginning of 1649, a tribunal of fifty people was formed. On January 20, it began its meetings at the Palace of Westminster. Karl was brought to court three times to testify. From the very beginning he declared that he did not recognize the right of the House of Commons to put him on trial, nor the right of the tribunal to condemn him. He considered the power appropriated by parliament to be usurpation. When they told him that he received power from the people and used it to harm the people, Charles replied that he received power from God and used it to fight the rebels. And when he was accused of starting a civil war and bloodshed, he replied that he took up arms to preserve the rule of law. It is obvious that each side was right in its own way, and if the case had been considered legally, the resolution of all legal difficulties would have taken more than one month. But Cromwell did not consider it possible to delay the process for so long. On January 27, the tribunal announced that “Charles Stuart,” as a tyrant, rebel, murderer and enemy of the English state, was sentenced to beheading. The king was given three days to prepare for death. He used them in prayers with Bishop Joxon. All these days, right up to the very last minute, he maintained exceptional courage. On January 30, Charles was beheaded on a scaffold placed near the Guategoll Palace, and a few days later parliament declared the monarchy abolished and proclaimed a republic.

All the monarchs of the world. Western Europe. Konstantin Ryzhov. Moscow, 1999.

Read further:

Literature:

Higham F. M., Charles I., L., 1932;

Wedgwood C. V., The Great Rebellion: v. 1-The King's peace. 1637-1641, L., 1955; v. 2 - The King's war. 1641-1647, L., 1958.

Can't be washed away by all the waters of the furious sea

Holy oil from the royal brow

And he is not afraid of human machinations

Whom the Lord appointed as viceroy.

W. Shakespeare "Richard III", Act III, Scene II"

On January 30, 1649, after a shameful trial, the English king Charles I of the Stuart dynasty was executed by Judaizing heretics - Puritans, revolutionaries of the 17th century. During the reign of his son Charles II, the martyr king was canonized as a monarch who accepted death for the Faith, for he sought to preserve the Episcopal Church and the apostolic reception in it (according to the Anglicans) and to protect church life and the monarchical foundations of the English state from encroachment heretics.

Portrait of King Charles I, painted in the 1630s.

Charles was the third son of King James I and became heir only in 1616, after the death of his two older brothers. As a child, he was a meek and submissive child, and in his youth he was distinguished by his piety (as, indeed, throughout his entire adult life), diligence and penchant for theological debates.

In the last years of his reign, King James I hatched plans for an alliance with Spain and wanted to marry his son to a Spanish princess. The Tsar's favorite, the Duke of Buckingham, convinced Charles to follow his bride to Madrid in the role of a wandering lover. This romantic adventure captivated Karl so much that even his father’s insistent arguments did not force him to abandon this idea. Karl and Buckingham arrived in Madrid in disguise, but here their appearance aroused more surprise than joy. Long negotiations came to nothing, and Charles returned to England a convinced enemy of Spain. Soon Jacob died, and Charles ascended to the English throne. The new king lacked neither courage nor military skill. With the virtues of the father of the family, he combined the virtues of the head of state. Unfortunately, during his reign, the king made many mistakes (and which of the rulers does not have them), was often too soft when he should have been harsh, and often made mistakes in choosing advisers.

From the very beginning of his reign, he had to face the willfulness and disrespect of his subjects. At the meeting of the first parliament of his reign in 1625, he demanded subsidies for the war with Spain. Deputies agreed to allocate 140 thousand pounds sterling for military needs and approved a “barrel tax” for this purpose, but only for one year. The angry king dissolved the chambers. Parliament in 1626 began its sessions with an attempt to place the royal favorite, the Duke of Buckingham, in court. Charles went to the House of Lords and announced that he accepted responsibility for all the orders of his minister. He again dissolved parliament, and in order to get money, he had to resort to a forced loan, which caused general indignation. With great difficulty, only minor funds were obtained, which were then spent without any benefit on the war with France. In 1628, Charles convened his third parliament.

Skirmishes between the deputies and the king began again. The Magna Carta, which was not remembered during the entire reign of the Tudors, was brought out of oblivion. Which is not surprising: under the syphilitic tyrant Henry VIII and his red-haired beast, daughter Elizabeth, stuttering “about liberties” was fraught, but under the meek Charles I...

On the basis of it, the House of Commons drew up the “Petition of Rights,” which was, in essence, a statement of the English Constitution. After much hesitation, Karl approved it. From that time on, the “petition” became the basic English law, and was constantly appealed to in clashes with the king. Charles, who agreed to such an important concession, did not gain anything in return, since Parliament did not agree to approve the subsidies and again demanded that Buckingham be brought to court. However, the Duke was killed in 1628 by the fanatic Felton. Charles dissolved parliament and ruled without it for the next eleven years.

The main work of the entire life of Sovereign Charles I(and this is what ultimately brought the martyr king to the chopping block) was concern for strengthening the autocratic royal power and concern for the greatness and prosperity of the Church of England. He directed all his efforts to, if possible, destroy or mitigate the harmful consequences of the Reformation.

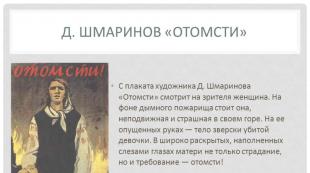

King Charles - Defender of the Faith. Engraving from 1651.

However, the Sovereign did not at all seek to return the Church of England to the bosom of the papal curia, but appealed to the times of the Undivided Church of the first 10 centuries of the existence of Christianity. In his own words, he wanted the Church of England to be more Catholic (that is, essentially Catholic! Orthodox!) than the contemporary papacy. Of course, Charles cannot be called Orthodox, but we can safely say that in his deeds and aspirations he was the forerunner of those remarkable Anglican figures who sought rapprochement with the Orthodox Church in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Hieromartyr Archbishop William Laud and King Charles I. Stained glass window in St. Mary's Church. USA, Southern California.

By order of the king, Archbishop Laudoux introduced celibacy of the clergy, the doctrine of purgatory, prayer for the dead, veneration of saints and the Virgin Mary, the doctrine of Communion as the actual Body and Blood of Christ (the doctrine of transubstantiation) and many other dogmas.

The king's church policy aroused particular resistance in Scotland, where the Calvinist heresy (Puritanism) had violently taken root.

In 1625, Charles I issued the Act of Revocation, which revoked all land grants from the kings of Scotland since 1540. This concerned, first of all, former church lands, secularized during the Reformation and illegally appropriated by the local nobility. The nobles could retain these lands in their ownership, but subject to monetary compensation, which went to support the church. This decree affected most of the Scottish nobility and caused widespread discontent, but the king refused to consider the Scots' petition. The Sovereign's faithful associate, Archbishop Laud of Canterbury, began severe persecution of the Puritans and forced many of them to emigrate to America. In 1633, during the king's first visit to Scotland, the local parliament was convened, which, under pressure from Charles I, approved an act of supremacy (supremacy) of the king in matters of religion.

Depiction of King Charles, founder of the Diocese of Edinburgh in the Anglican Church in Scotland.

At the same time, Charles I introduced a number of Anglican canons into Scottish worship and formed a new bishopric - Edinburgh, headed by William Forbes, an ardent supporter of Anglican reforms. This caused an explosion of indignation among Scottish heretics, but Charles I again refused to consider the petition of the Scottish nobles against church innovations and the king's manipulation of parliamentary elections. One of the authors of the petition, Lord Balmerino, was arrested and sentenced to death in 1634 on charges of treason. Almost from the very beginning of his reign, Charles I, who had great respect for bishops, began to actively attract them to senior government positions. The first person in the royal administration of Scotland was John Spottiswoode, Archbishop of St. Andrews, Lord Chancellor since 1635. The majority in the royal council passed to the bishops to the detriment of the Scottish aristocrats, the bishops also actually began to determine the composition of the Committee of Articles and candidates for the posts of justices of the peace. A significant part of the representatives of the Scottish episcopate of that time did not enjoy authority among their flock, which was mired in heresy and had no connections with the nobility. The aristocracy, pushed out of government, did not have access to the king, whose court was almost constantly located in London. In 1636, signed by the king, the reformed canons of the Scottish Church were published, in which there was no mention of presbyteries and parish assemblies, and in 1637 a new liturgy was introduced, providing for a number of Anglican elements, the invocation of saints and the Virgin Mary, and rich church decoration. These reforms were perceived in Scottish society as an attempt to restore Catholic rites, which in turn led to an uprising in Scotland on July 23, 1637, followed by the so-called. "Bishop Wars".

In addition to the Puritans, the Tsar had to fight the greed of his subjects (primarily aristocrats), who did not want to fork out for state needs. Seeking funds, the king introduced new taxes with his authority. Thus, in 1634, a “ship duty” was introduced. But collecting these taxes became more and more difficult every year. The government had to initiate legal proceedings against malicious tax evaders, which caused loud murmurs of public indignation. Pamphlets directed against the king began to appear in large quantities. The police searched for their authors and punished them. This in turn gave rise to new indignation. In Scotland, where the Puritan position was much stronger than in England, the king's policies led, as mentioned above, to a powerful uprising. Leslie's army of twenty thousand invaded England from Scotland. Charles did not have the strength to fight her, and in 1640 he had to convene the fourth parliament.

The king hoped that, under the influence of patriotism, the deputies would allow him to raise the funds necessary to wage the war. But he was wrong once again. At the very first meeting of the House of Commons, the deputies announced their intention to review everything that had been done without their participation over these eleven years. The king declared parliament dissolved, but he was in a very difficult position: his army did not have high combat capability and was constantly defeated in the war. In November 1640, he unwillingly convened a new parliament, which went down in history under the name of the Long. On November 11, deputies demanded a trial of the royal minister Strafford. On the same day he was arrested and, together with Archbishop Laud, imprisoned. Everyone who took any part in collecting the “ship duty” was persecuted. Without any military force in its hands and relying only on the London crowd, Parliament actually seized government control into its own hands. Karl made one concession after another. Ultimately, he was forced to sacrifice his minister, and Strafford was beheaded in May 1641. Parliament soon abolished all tribunals that did not obey the general rules, including the Star Chamber (Supreme Court for Political Affairs) and the High Commission (Supreme Tribunal for Religion). Laws were passed stating that the interval between the dissolution of the previous parliament and the convening of a new one could not exceed three years and that the king could not dissolve parliament against his will.

Charles defended the divine right of kings as best he could. In January 1642, he accused five members of the House of Commons of secret relations with the Scots and demanded their arrest. He himself went to Westminster, accompanied by nobles and bodyguards, to capture the suspects, but they managed to flee to the City. Karl, annoyed, hurried after them, but failed to take the troublemakers into custody. The sheriffs refused to carry out his order, and a violent crowd, running from all sides, greeted the king with loud cries of “Privilege! Privilege!" Karl saw that he could do nothing and left London that same day. Five members of the House of Commons solemnly returned to Westminster under the protection of the city police.

The king settled in York and began to prepare for a campaign against the capital. All attempts to peacefully resolve the conflict ended in failure, as both sides showed intransigence. Parliament demanded for itself the right to appoint and dismiss ministers and sought to subordinate all branches of government to its control. Charles replied: “If I agree to such conditions, I will become only a ghostly king.” Both sides were gathering troops. Parliament introduced taxes and formed an army of 20 thousand. At the same time, the king's supporters flocked to the northern counties. The first battle, which took place in October at Edgegill, did not have a decisive outcome. But soon uprisings began in the western counties in favor of the king. The city of Bristol surrendered to the Royalists. Having firmly established himself in Oxford, Charles began to threaten London, but resistance to him grew with each passing month. Since all the pious bishops sided with the king, parliament in 1643 announced the abolition of bishoprics and the introduction of Presbyterianism. Since then, nothing has prevented a close rapprochement with the rebel Scottish Puritans. In 1644, the king had to simultaneously wage war against the army of Parliament and the army of Leslie. On July 3 the royalists were defeated at Merston Moor. The decisive role in this victory was played by Oliver Cromwell's detachment, composed of fanatical Puritans. The northern counties recognized the authority of Parliament. For some time, Charles continued to win victories in the south. Throughout this war, he showed, along with his usual fearlessness, composure, energy and outstanding military talents. The Parliamentary army under Essex was surrounded and capitulated in Cornwall on 1 September. This defeat led to the fact that the Independents (extreme Puritans) led by Cromwell took over in the House of Commons. The people in the capital were filled with enthusiasm. The Independents banned all entertainment; time was divided between prayer and military exercises. In a short time, Cromwell formed a new army, distinguished by extremely high fighting spirit. On June 14, 1645, she met the royalists at Nezby and inflicted a decisive defeat on them. The king retreated, leaving five thousand dead and one hundred banners on the battlefield. In the following months, parliament extended its influence throughout the country.

Accompanied by only two people, Charles fled to Scotland, wanting to get support from his fellow countrymen. But he miscalculated. The Scots captured the king and handed him over to parliament for 800 thousand pounds sterling. Karl found himself a prisoner in Golmeby. True, even now his situation was far from hopeless.

The House of Commons offered him peace on the condition that he agree to the destruction of the episcopal structure of the Church of England and submit the army to the subordination of parliament for twenty years. Soon a third force intervened in these negotiations. During the war years, the army turned into an independent and powerful organization with its own interests and was not always ready to carry out the instructions of parliament. In June 1647, several squadrons captured the king at Golmsby and took him under escort to their camp. Here negotiations began between the king and the commanders of the army. The conditions proposed by these latter were less restrictive than parliamentary ones. Thus, the period for which the king had to give up command of the army was reduced to ten years. Karl hesitated to make a final decision - he hoped that he could still be the winner; on November 11, he fled from Hampton Court to the Isle of Wight. Here, however, he was immediately captured by Colonel Grommond and imprisoned in Kerisbroke Castle. However, the king's flight served as a signal for a second civil war. Violent royalist revolts broke out in the southeast and west of the country. The Scots, to whom Charles had agreed to promise the preservation of their Presbyterian “church,” supported him. But even after this, the king had no hope of victory. Cromwell defeated the Scots and, pursuing them, entered Edinburgh. The rebellious Colchester capitulated to Fairfax's army.

In July 1648, new negotiations began. Charles accepted all the demands of the victors, except for the abolition of episcopacy. For for the Sovereign, consent to church reform according to the patterns of heretics was tantamount to renouncing Christ. In his Newport Declaration a year before his execution, he firmly stated

I am clearly aware that the Episcopal government is most consonant with the Word of God, and this ecclesiastical institution was instituted and practiced by the apostles themselves, and from them the apostolic succession is preserved, and it will be preserved until the end of time among all bishops in Christ's Churches, and therefore my conscience does not allow I should agree to the government's condition.

Parliament was ready to make peace on these terms, but the army, imbued with the Puritan spirit, fiercely opposed this concession. On December 6, a detachment of soldiers under the command of Colonel Pride expelled 40 deputies from the House of Commons who were inclined to compromise with the king. The next day, the same number were expelled. Thus, independents, acting in concert with the army, received a majority in parliament. In reality, this coup meant the beginning of the one-man rule of the bloody dictator Cromwell. He entered the capital as a triumphant man and took up residence in the royal rooms of Guategall Palace as sovereign of the state.

Cromwell's soldiers mock God's Anointed as the guards mocked Christ.

Now, on his initiative, parliament decided to put the king on trial as a rebel who had started a war with his own people. Charles was taken under guard to Windsor and then to St. James's Palace. At the beginning of 1649, a tribunal of fifty people was formed. On January 20, it began its meetings at the Palace of Westminster. Karl was brought to court three times to testify.

The trial of King Charles.

From the very beginning he declared that he did not recognize the right of the House of Commons to put him on trial, nor the right of the tribunal to condemn him. He considered the power appropriated by parliament to be usurpation. When they told him that he received power from the people and used it to harm the people, Charles replied that he received power from God and used it to fight the rebels. Moreover, he demanded that his accusers prove the illegality of his claims to authority from God by reference to the Holy Scriptures. When it was pointed out to him that kings were elected in ancient England, he objected - starting from the 11th century, royal power in the country was hereditary. And when he was accused of starting a civil war and bloodshed, he replied that he took up arms to preserve the rule of law. It is obvious that each side was right in its own way, and if the case had been considered legally, the resolution of all legal difficulties would have taken more than one month. But Cromwell did not consider it possible to delay the process for so long. On January 27, the tribunal announced that “Charles Stuart,” as a tyrant, rebel, murderer and enemy of the English state, was sentenced to beheading.

The sympathies of the vast majority of those gathered in Westminster Hall were on the side of the king. When, in the afternoon on the last day of the meeting, Charles was denied the right to be heard and led to the exit, a quiet but clearly audible roar of voices rushed through the hall: “God save the king!” The soldiers, trained by their corporals and spurred on by their own courage, responded to this with cries of “Justice! Justice! Execution! Execution!

King Charles is led to execution. Artist Ernst Crofts.

The king was given three days to prepare for death. He used them in prayers with Bishop Joxon. All these days, right up to the very last minute, he maintained exceptional courage.

Execution of King Charles I. Stained glass window of the church in Dark Harbor. England.

On the morning of January 30, 1649, Charles was taken to Whitehall. It was snowing, and the king put on warm underwear. He walked briskly, accompanied by guards, saying: “Make way.” His final journey was about half a mile and brought him to the Banqueting House. Most of those who signed the death warrant were horrified by the act committed, for the severity of which they still had to bear retribution.

At one o'clock in the afternoon Karl was informed that his time had come. Through the high window of the Banqueting House he emerged onto the scaffold. The soldiers kept the huge crowd at bay. The king looked with a contemptuous smile at the instrument of execution, with the help of which the sentence was to be carried out if he refused to obey the decision of the tribunal. He was allowed to say a few words if he wished. The troops could not hear him, and he turned to those who stood near the platform. He said that he was dying as a good Christian, that he forgives everyone, especially those who are responsible for his death (without mentioning anyone by name). He wished them repentance and expressed his desire that they would find a way to peace in the kingdom, which could not be achieved by force.

Then he helped the executioner tuck his hair under his white satin cap. He laid his head on the scaffold, and at his signal his head was cut off with one blow. The severed head was presented to the people, and someone exclaimed: “This is the head of a traitor!”

A huge crowd flocked to the place of execution, experiencing strong, albeit restrained, feelings. When those gathered saw the severed head, thousands of those present released such a groan, wrote one contemporary, that he had never heard before and had no desire to hear in the future.

A few days later, parliament declared the monarchy abolished and proclaimed a republic.

It is interesting that the events of the English Revolution caused a sudden break in the diplomatic relations between England and Russia that had been steadily developing for almost a hundred years. The reason for the break was the execution of King Charles I. On June 1, 1649, Alexei Mikhailovich issued a decree on the expulsion of all British merchants with the following words: “and now... the whole earth has committed a great evil deed, their sovereign, King Charles, was killed to death... and for such an evil “You didn’t happen to be in the Moscow state.” Until the execution of the king, the government of Alexei Mikhailovich closely monitored the events of the revolution, but responded to requests for help with silence, delaying negotiations. However, the execution of the king probably caused unpleasant associations with the 1648 uprising in Moscow; Behind the expulsion of British merchants (most of whom, following the example of the Moscow Company, were supposed to support parliament), one can discern the Moscow government’s fear for the stability of its own positions.

After the execution of Charles I, translations of English brochures and pamphlets published by the royalists appeared in Moscow. In the list of translations made by Epiphany Slavinetsky, the work “about the murder of the king of Aggelsky from the Latin language…” that has not reached the composition is mentioned. More famous is “The Legend of How the English King Charles Stewart was executed...”. At the same time, in Britain (1650) a false “Declaration” made by the royalists appeared, supposedly a translation of the decree of Alexei Mikhailovich. Around the same time, in 1654, an unexpected anonymous pamphlet appeared in London, signed by J.F., the author of which, an obvious admirer of Boris Godunov, praised Russia for the democratic foundations of legislation; This is an unexpected work that contradicts the traditional opinion of the British about the Russian state structure.

Charles was buried on the night of 7 February 1649 in St George's Chapel at Windsor Castle. The king's son, King Charles II, later planned to build a royal mausoleum in his father's honor, but unfortunately was unable to bring his idea to fruition.

After the restoration of the monarchy and church hierarchy in England on May 29, 1660, by decision of the church councils in Canterbury and York, the name of King Charles was included in the church calendar in the Book of Common Prayer, where he was commemorated on the day of his death. During the reign of Queen Victoria, the great feast in honor of St. Charles was removed from the liturgical texts at the request of the House of Commons; January 30th is listed as a "Small Celebration" only. The holiday was restored in the 1980 edition of the Alternative Book of Worship and in the General Worship Book in 2000. However, the holiday has not yet been included in the Book of Common Prayer.

In England, Canada, Australia and even in the USA, an initially republican country, there are religious communities dedicated to the memory of the martyr king Charles I. In England and English-speaking countries there are several churches in honor of the holy king.

Compiled by:

All the monarchs of the world. Western Europe. Konstantin Ryzhov. Moscow, 1999