Vitus Bering's Kamchatka Expeditions. Kamchatka expeditions (Vitus Bering) 1 Kamchatka Bering expedition

First Kamchatka expedition

Being inquisitive by nature and, like an enlightened monarch, concerned about the benefits for the country, the first Russian emperor was keenly interested in travel descriptions. The king and his advisers knew about the existence of Anian - that was the name of the strait between Asia and America at that time - and expected to use it for practical purposes. At the end of 1724, Peter I remembered “... something that I had been thinking about for a long time and that other things prevented me from doing, that is, about the road across the Arctic Sea to China and India ... Will we not be happier in exploring such a path than the Dutch and the British? ... "and , without delay, drew up an order for an expedition. The captain of the 1st rank was appointed its head, later - the captain-commander, forty-four-year-old Vitus Jonassen (in Russian usage - Ivan Ivanovich) Bering, who had served in Russia for twenty-one years.

The tsar handed him a secret instruction written in his own hand, according to which Bering was to "... in Kamchatka or in another ... place to make one or two boats with decks"; on these boats to sail "near the land that goes to the north ... look for where it met with America ... and visit the shore ourselves ... and put it on the map, come here."

The land going to the north (north) is nothing more than the mysterious "Land of João da Gama" - a large landmass, allegedly stretching in a northwesterly direction near the coast of Kamchatka (on the German map of "Kamchadalia" 1722 that the tsar had of the year). Thus, in fact, Peter I set the task for the Bering expedition to reach this land, pass along its coast, find out if it connects with North America, and trace the coast of the mainland south to the possessions of European states. The official task was to resolve the issue of "whether America came together with Asia" and the opening of the Northern Sea Route.

The first Kamchatka expedition, which initially consisted of 34 people, set off on the road from St. Petersburg on January 24, 1725. Moving through Siberia, they went to Okhotsk on horseback and on foot, on ships along the rivers. The last 500 km from the mouth of the Yudoma to Okhotsk, they dragged the heaviest loads, harnessing themselves to the sledges. Terrible frosts and famine reduced the composition of the expedition by 15 people. At least the following fact speaks of the pace of movement of travelers: the advance detachment led by V. Bering arrived in Okhotsk on October 1, 1726, and the group of Lieutenant Martyn Petrovich Shpanberg, a Dane in the Russian service, who closed the expedition, reached there only on January 6, 1727. To to survive until the end of winter, people had to build several huts and sheds.

The road through the expanses of Russia took two years. On this entire path, equal to a quarter of the length of the earth's equator, Lieutenant Alexei Ilyich Chirikov determined 28 astronomical points, which made it possible for the first time to reveal the true latitudinal extent of Siberia, and, consequently, the northern part of Eurasia.

From Okhotsk to Kamchatka, the expedition members traveled on two small ships. For the sea continuation of the journey, it was necessary to build and equip the boat “St. Gabriel", on which the expedition went to sea on July 14, 1728. As the authors of “Essays on the History of Geographical Discoveries” note, V. Bering, having misunderstood the king’s intention and violating the instructions that ordered him to first go from Kamchatka to the south or east, headed north along the coast of the peninsula, and then northeast along the mainland .

“As a result,” the “Essays ...” read further, “more than 600 km of the northern half of the eastern coast of the peninsula were photographed, the Kamchatka and Ozernoy peninsulas, as well as the Karaginsky Bay with the island of the same name ... The sailors also put on the map 2500 km of the coastline of the North- East Asia. Along most of the coast they noted high mountains, and covered with snow in summer, approaching in many places directly to the sea and rising above it like a wall. In addition, they discovered the Gulf of the Cross (not knowing that it had already been discovered by K. Ivanov), the Bay of Providence and the island of St. Lawrence.

However, the "Land of João da Gama" was not shown. V. Bering, not seeing either the American coast or the turn to the west of the Chukchi coast, ordered A. Chirikov and M. Shpanberg to state in writing their opinions on whether the presence of a strait between Asia and America can be considered proven, whether to move further north and how far . As a result of this "written meeting" Bering decided to go further north. On August 16, 1728, the sailors passed through the strait and ended up in the Chukchi Sea. Then Bering turned back, officially motivating his decision by the fact that everything was done according to the instructions, the coast does not extend further to the north, but “nothing came to the Chukotsky, or Eastern, corner of the earth.” After spending another winter in Nizhnekamchatsk, in the summer of 1729, Bering again made an attempt to reach the American coast, but after walking a little more than 200 km, due to strong wind and fog, he ordered to return.

The first expedition described the southern half of the eastern and a small part of the western coast of the peninsula for more than 1000 km between the mouths of Kamchatka and Bolshaya, revealing the Kamchatka Bay and Avacha Bay. Together with Lieutenant A.I. Chirikov and midshipman Pyotr Avraamovich Chaplin, Bering compiled the final map of the voyage. Despite a number of errors, this map was much more accurate than the previous ones and was highly appreciated by D. Cook. A detailed description of the first marine scientific expedition in Russia was preserved in the ship's log, which was kept by Chirikov and Chaplin.

The northern expedition would not have been successful without auxiliary campaigns led by Cossack colonel Afanasy Fedotovich Shestakov, captain Dmitry Ivanovich Pavlutsky, surveyor Mikhail Spiridonovich Gvozdev and navigator Ivan Fedorov.

It was M. Gvozdev and I. Fedorov who completed the opening of the strait between Asia and America, begun by Dezhnev and Popov. They examined both sides of the strait, the islands located in it, and collected all the materials needed to put the strait on the map.

| |

The results of the expedition for the Russian were colossal. Bering has come a long way. The gradual development of the eastern outskirts of the empire began. During the expedition, Kamchatka was studied and mapped, cities and peoples, relief, hydrography and much, much more were studied ... but in St. Petersburg the results of Bering's voyage were very dissatisfied. At the head of the Admiralty were at that time people with broad views, "the chicks of Petrov's nest." They believed that after Bering's first expedition "about the non-connection" of Asia and America "it is doubtful and unreliable to establish itself truly" and that it is necessary to continue research. Bering, by his actions during the First Kamchatka Expedition, showed that he could not direct such research. But he was supported by influential "Bironites". Bering was already familiar with the area, and he was asked to draft a new expedition.

This project at the Admiralty Board, headed by Admiral Nikolai Fedorovich Golovin, with the participation of the Chief Secretary of the Senate Ivan Kirillovich Kirilov, Captain-Commander Fedor Ivanovich Soimonov and Alexei Ilyich Chirikov, was radically revised and expanded.

As we have seen, Bering's First Kamchatka Expedition was not crowned with new geographical discoveries. She only partly confirmed what Russian sailors had long known and what was even put on the map of Ivan Lvov in 1726. The only thing that the expedition proved with complete obviousness was the great difficulty of transporting more or less heavy loads to Okhotsk and Kamchatka by land. And Okhotsk for a long time played the same role for the Sea of Okhotsk, on which the interests of the state were growing, the same role that Arkhangelsk played for the White Sea.

It was necessary to look for cheaper sea routes. Such routes could be the Northern Sea Route, skirting Asia from the north, and the southern route, skirting Africa and Asia or South America from the south.

At that time, it was already known that almost the entire Northern Sea Route, albeit in parts, was traversed by Russian sailors in the 17th century. It had to be checked, it had to be put on the map. At the same time, the Admiralty Board discussed the issue of sending an expedition to the Far East by the southern sea route, but this issue was not resolved at that time. The vast expanses of Eastern Siberia were comparatively recently annexed to Russia. It was necessary to collect more or less accurate information about this vast country.

Finally, information reached the Admiralty Boards that somewhere around 65N. North America comes relatively close to Asia's northeast bulge. On the position of the western coast of North America between 45 and 65N. nothing was known. The extension of Japan to the north was known only up to 40N. It was assumed that the large and indefinite Ezzo Land and Company Land were located to the north, and between them the island of the States, allegedly seen in 1643 by the Dutch navigators De Vries and Skep. To the east of them between 45 and 47N. "Land da Gama" was drawn, allegedly discovered in 1649 by an unknown navigator Zhuznom da Gama. It was necessary to check the existence of these lands, to bring their inhabitants into Russian citizenship, if these lands exist. Most importantly, it was necessary to find sea routes to the already known rich countries to North America and Japan and, if possible, establish trade relations with them.

On February 23, 1733, the Senate finally approved the plan for a new expedition. Vitus Bering was again appointed its head, despite the fact that his voyages in 1728 and 1729. already showed his incompetence and indecision. But if Bering was appointed to the First Kamchatka Expedition because he was in the "East Indies and knows how to get around", then he was appointed to the Second Kamchatka Expedition partly because he was already in Siberia and the Pacific Ocean. In 1732, under the leadership of the President of the Admiralty Colleges, Admiral N.F. Golovin developed a new instruction for Bering, providing for the construction of three dubel-boats with decks with 24 oars for the study of the northern seas; one was decided to be built in Tobolsk on the Irtysh and two in Yakutsk on the Lena. On two ships they were supposed to go to the mouths of the Ob and Lena rivers, and then by sea near the coast to the mouth of the Yenisei towards each other. And on the third double-boat, sail east to Kamchatka. It was also supposed to explore the seashore from the city of Arkhangelsk to the Ob River.

But the main task of V. Bering's expedition was still the discovery of the western shores of North America and the strait separating it from Asia.

After the approval of the instruction by the Senate at the end of 1732, active preparations for the Second Kamchatka Expedition immediately began. It was now headed by Captain-Commander V. Bering. Nearly a thousand people were sent on the expedition. In addition to the crews of the future six ships, along with navigators and sailors, shipwrights, caulkers, carpenters, sailboats, healers, surveyors, and soldiers for protection rode. Several professors of the Academy of Sciences were also included in the "Kamchatka" expedition (as it was officially called).

In the spring of 1733, wagon trains with anchors, sails, rope and cannons stretched from St. Petersburg along the last sledge track. Among the leaders of the future detachments was the commander of the detachment assigned to explore the coast to the west of the Lena River, Lieutenant Vasily Vasilyevich Pronchishchev, with his young wife Maria, who decided to accompany her husband on the upcoming long-term wanderings in northern Siberia.

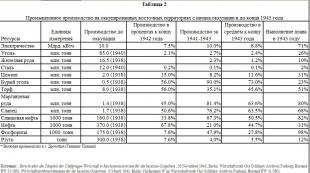

Tab. 1 Catalog of cities and significant places mapped during the First Kamchatka Expedition.

|

Cities and places of honor |

Length from Tobolsk to the east |

|||

|

City of Tobolsk |

||||

|

Samarovsky pit |

||||

|

The town of Sorgut |

||||

|

Narym town |

||||

|

Ketskoy jail |

||||

|

Losinobor Monastery |

||||

|

Makovsky prison |

||||

|

City of Yeniseisk |

||||

|

Kashin Monastery |

||||

|

At the mouth of the Ilim River, the village of Simakhina |

||||

|

Gorook Ilimsk |

||||

|

Ust-Kutsk jail |

||||

|

Kirinsky prison |

||||

|

City of Yakutsk |

||||

|

Okhotsk prison |

||||

|

Mouth of the Bolshoi River |

||||

|

Upper Kamchatka Ostrog |

||||

|

Lower Kamchatka Ostrog |

||||

|

Mouth of the Kamchatka River |

||||

|

Corner of the Holy Apostle Thadeus |

||||

|

Gulf of the holy cross vestibule |

||||

|

Onaya gulf core corner |

||||

|

Bay of the Holy Transfiguration |

||||

|

Chukotka corner to the east |

||||

|

Saint Lawrence Island |

||||

|

Saint Deomede Island |

||||

|

The place from which they returned |

||||

|

Kamchatka land to the south |

The famous English navigator J. Cook 50 years after Bering, in 1778, passing along the same path along the shores of the Bering Sea, checked the accuracy of the mapping of the coasts of northeast Asia, made by V. Bering, and on September 4, 1778 made the following entry in his diary: "Paying tribute to the memory of Bering, I must say that he marked this coast very well, and determined the latitudes and longitudes of its capes with such accuracy that it was difficult to expect, given the methods of definitions that he used." Convinced that the northwestern coast of Asia was put on the map by Bering quite correctly, on September 5, 1778, Cook wrote the following about this: “Convinced of the accuracy of the discoveries made by the said gentleman Bering, I turned to the East.

F.P. Litke, who 100 years later, in 1828, sailed along the coasts mapped by Bering, checked the accuracy of his navigational, astronomical and other definitions of coastal points and gave them a high rating: "Bering did not have the means to produce inventories with the accuracy that is required now; but the line of the coast, simply outlined along its path, would have a greater resemblance to its present position than all the details that we found on the maps.

V.M. Golovnin admired the fact that Bering gave names to the discovered lands not in honor of noble persons, but of the common people. “If the current navigator succeeded in making such discoveries as Bering and Chirikov did, then not only all the capes, islands and American bays would receive the names of princes and counts, but even on bare stones he would seat all the ministers and all the nobility; and compliments Vancouver, to the thousand islands, capes, etc., which he saw, distributed the names of all the nobles in England and his acquaintances ... Bering, on the contrary, having discovered the most beautiful harbor, named it after his ships: Petra and Paul; a very important cape in America called Cape St. Elijah ... a group of fairly large islands, which now would certainly have received the name of some glorious commander or minister, he called Shumagin islands because he buried a sailor who died with him on them ".

The first Kamchatka expedition 1725-1730 occupies a special place in the history of science. She is

was the first major scientific expedition in the history of the Russian Empire, undertaken by decision of the government. In organizing and conducting the expedition, a great role and merit belongs to the navy. The starting point of the First Kamchatka Expedition was the personal decree of Peter I on the organization of the "First Kamchatka Expedition" under the command of Vitus Bering, December 23, 1724. Peter I personally wrote instructions to Bering.

The sea route from Okhotsk to Kamchatka was discovered by the expedition of K. Sokolov and N. Treska in 1717, but the sea route from the Sea of Okhotsk to the Pacific Ocean had not yet been opened. It was necessary to walk across the mainland to Okhotsk, and from there to Kamchatka. There, all supplies were delivered from Bolsheretsk to the Nizhnekamchatsky prison. This created great difficulties in the delivery of materials and provisions. It is difficult for us even to imagine all the incredible burden of the journey through the deserted thousand-mile tundra for travelers who do not yet have organizational skills. It is interesting to see how the journey proceeded, and in what form people and animals arrived at their destination. Here, for example, is a report from Okhotsk dated October 28: “Provisions sent from Yakutsk by land arrived in Okhotsk on October 25 on 396 horses. On the way, 267 horses disappeared and died for lack of fodder. During the journey to Okhotsk, people suffered a great famine, they ate belts from a lack of provisions,

leather and leather pants and soles. And the horses that arrived fed on grass, getting it out from under the snow, since they did not have time to prepare hay due to their late arrival in Okhotsk, but it was not possible; all froze from deep snow and frost. And the rest of the servants arrived by sledges on dogs in Okhotsk. From here the cargoes were transported to Kamchatka. Here, in the Nizhnekamchatsky prison, on April 4, 1728, under the leadership of Bering, a boat was laid, which in June of the same year was launched and named "St. Archangel Gabriel."

On this ship, Bering and his companions in 1728 sailed through the strait, which was later named after the head of the expedition. However, due to dense fog, it was not possible to see the American coast. Therefore, many decided that the expedition was unsuccessful.

Results of the I Kamchatka expedition

Meanwhile, the expedition determined the extent of Siberia; the first sea vessel in the Pacific Ocean was built - "Saint Gabriel"; open and mapped 220 geographical features; the presence of a strait between the continents Asia and America was confirmed; the geographical position of the Kamchatka Peninsula was determined. The map of V. Bering's discoveries became known in Western Europe and immediately entered the latest geographical atlases. After the expedition of V. Bering, the outlines of the Chukotka Peninsula, as well as the entire coast from Chukotka to Kamchatka, take on maps a look close to their modern images. Thus, the northeastern tip of Asia was mapped, and now there was no doubt about the existence of a strait between the continents. In the first printed report on the expedition, published in the St. Petersburg Vedomosti on March 16, 1730, it was noted that Bering reached 67 degrees 19 minutes north latitude and confirmed that “there is a truly northeastern passage, so that from Lena ... by water to Kamchatka and further to Japan, Khina

(China) and the East Indies, it would be possible to get there.

Of great interest to science were geographical observations and travel records of the expedition members: A.I. Chirikova, P.A. Chaplin and others. Their descriptions of coasts, relief,

flora and fauna, observations of lunar eclipses, currents in the oceans, weather conditions, observations about earthquakes, etc. were the first scientific data on the physical geography of this part of Siberia. The descriptions of the expedition members also contained information about the economy of Siberia, ethnography, and others.

The first Kamchatka expedition, which began in 1725 on the instructions of Peter I, returned to St. Petersburg on March 1, 1730. V. Bering presented to the Senate and the Admiralty Board a report on the progress and results of the expedition, a petition for promotion and awarding officers and privates.

Sources:

1. Alekseev A.I. Russian Columbuses. - Magadan: Magadan book publishing house, 1966.

2. Alekseev A. I. Brave Sons of Russia. - Magadan: Magadan book publishing house, 1970.

3. Berg A. S. Discovery of Kamchatka and Bering's expedition 1725-1742. - M .: Publishing house of the Academy

Sciences of the USSR, 1946.

4. Kamchatka XVII-XX centuries: historical and geographical atlas / Ed. ed. N. D. Zhdanova, B. P. Polevoy. – M.: Federal service of geodesy and cartography of Russia, 1997.

5. Pasetsky V. M. Vitus Bering. M., 1982.

6. Field B. P. Russian Columbuses. - In the book: Nord-Ost. Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, 1980.

7. Russian Pacific epic. Khabarovsk, 1979.

8. Sergeev VD Pages of the history of Kamchatka (pre-revolutionary period): teaching aid. - Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky: Far Eastern Book Publishing House, Kamchatka Branch, 1992.

While England, France and Holland shared the colonial legacy of Spain and Portugal, a new world power was rapidly rising in the east of Europe. Having victoriously ended the war with Turkey, Russia, under the leadership of Peter I, reached the shores of the Sea of Azov. To establish direct ties with the West, it remained to return the Russian lands occupied by Sweden, and thus break through to the Baltic. The Northern War, which lasted more than 20 years, ended in complete victory: under the Treaty of Nystadt in 1721, Russia received lands in Karelia and the Baltic states with the cities of Narva, Revel, Riga and Vyborg. And immediately after that, as a result of the Persian campaign, the western coast of the Caspian Sea with Derbent and Baku was conquered. Russia strengthened its positions in the west and south. What happened in the east?

Kamchatka is the most distant Russian territory. Chukotka, of course, is to the east, but in order to get to Kamchatka by land, and not by water or air, you must first go through Chukotka. Therefore, Kamchatka was discovered later than the rest of the mainland territories of Russia. For a long time, this achievement was attributed to the Cossack Pentecostal Vladimir Vasilyevich Atlasov, who in 1697 came here from Anadyr at the head of a large detachment. Atlasov overlaid yasak on the local population, built two prisons, and on the bank of one of the tributaries of the Kamchatka River he installed a large cross, a symbol of the annexation of a new land to Russia. However, Atlasov, whom A. S. Pushkin called "Kamchatka Yermak", went to the peninsula in the footsteps of Luka Staritsyn (Morozko), who had been there several years earlier.

There is evidence of Russian explorers staying in Kamchatka even in more remote times. According to some historians, almost 40 years before Atlasov, Fyodor Chukichev and Ivan Kamchatoy passed a significant part of the peninsula; in honor of the latter, the largest local river was named, and only then the peninsula itself. The explorer of Kamchatka, S.P. Krasheninnikov, claimed that even earlier, in 1648, a storm had thrown Fedot Popov and Gerasim Ankidinov, Semyon Dezhnev's companions, here.

But it was after Atlasov's campaign that the annexation of Kamchatka to Russia began. Moreover, thanks to him, it became known in Moscow that some kind of large land lies to the east of Chukotka. Neither Atlasov nor the others saw her, but in winter, when the sea froze, foreigners came from there, bringing "sable" (in fact, it was an American raccoon). Simultaneously with the news about the land east of Chukotka, Atlasov brought to Moscow information about Japan, and at the same time the Japanese Denbey, captured by the Russians in Kamchatka.

In the reign of Peter I, Russian science took leaps and bounds forward. The need for its development was dictated by practical needs, economic and military. So, by order of Peter I, the beginning of the geographical study of the country and mapping was laid. A large detachment of travelers and geodesists trained at the Navigation School and the Naval Academy began to study the vast country. In 1719, Ivan Evreinov and Fyodor Luzhin, on behalf of the Tsar, surveyed Kamchatka and the Kuril Islands and compiled their maps.

Peter I attached paramount importance to the study of trade routes, in particular to India and China. In this sense, Atlasov's information about Japan was of undoubted interest. However, the king was even more interested in information about the mysterious big land near Chukotka. Peter I corresponded with many scientists, including Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. The latter was extremely interested in the question: are America and Asia separated or do they converge somewhere? And the place where two continents can meet is just east of Chukotka. Leibniz repeatedly wrote about this to Peter I. Note that Dezhnev's discovery went unnoticed for a long time - even in Russia.

Sending Evreinov and Luzhin to Kamchatka, Peter I gave them the task of determining the location of America. For obvious reasons, surveyors could not solve this problem. In December 1724, shortly before his death, the emperor wrote instructions for the First Kamchatka Expedition, which was to find out whether Asia was connected to America in the north. To do this, it was necessary to get to Kamchatka, build one, or better two deck boats there and go to them in a northerly direction. Having found America, the expedition had to move south along its coast - to the first city founded by Europeans, or to the first oncoming European ship. It was necessary to map all open lands, straits and settlements, collect information about the peoples who inhabited the northeast of Russia and the northwest of America, and, if possible, begin trade with America and Japan.

Peter appointed Vitus Bering, a Dane, who had been in the Russian service for more than 20 years, as the head of the expedition. Vitus Jonassen Bering, born in 1681 in Horsens, was trained in the naval cadet corps in Holland, sailed the Baltic and Atlantic, and visited the East Indies. Being invited to Russia by Peter I, he participated in the Russian-Turkish and Northern wars. Bering's assistants were Martin (Martyn Petrovich) Shpanberg, also a native of Denmark, and a graduate of the Naval Academy Alexei Ilyich Chirikov.

The expedition was equipped immediately, but ... First, several groups traveled to Vologda, then more than a month to Tobolsk. Several detachments again went through Siberia - sometimes on horseback, sometimes on foot, but mostly along the rivers. In the summer of 1726 we reached Yakutsk. From here it was necessary to go more than 1000 km to Okhotsk - through the mountains, through the swamps, and even with tools, sails, anchors for ships that were planned to be built for a sea voyage. The horses could not endure the hardships of the journey, and every single one fell. Now the loads were carried on boards up the Maya and Yudoma, and when winter came, on sleds.

Only in January 1727 did the expedition reach Okhotsk. Even earlier, Bering's group arrived there, moving light. Here, travelers were already waiting for the Shitik (a boat with sewn sides) “Fortune”. In September, the expedition members, along with all the equipment, moved on the "Fortune" to the western coast of Kamchatka, to Bolsheretsk, then by dog sled - to the eastern coast. In March 1728 the expedition arrived in Nizhnekamchatsk.

The boat "St. Gabriel" was built here, which in July 1728 went north. From the first day of the voyage, the navigators recorded the results of navigational and astronomical observations in the logbook, took bearings from mountains, capes and other coastal objects. Based on all these measurements, maps were drawn up. On the way to the north, the expedition discovered the bays of Karaginsky, Anadyrsky, Providence Bay and Cross Bay, St. Lawrence Island.

August 16 "Saint Gabriel" reached 67 ° N. sh. A day earlier, in the west, the sailors saw mountains - apparently, it was Cape Dezhnev. Thus, the Bering expedition for the first time after Dezhnev passed through the strait between Asia and America, this time from the south. Travelers did not see the opposite, American coast: the distance between the continents at the narrowest point of the strait is 86 km. Since there was open sea ahead, and the Asian coast went west, Bering decided that the existence of the strait could be considered proven, and turned back. Only Chirikov offered to continue sailing in a westerly direction, to the mouth of the Kolyma, in order to finally be convinced of the validity of this assumption. But Bering and Spanberg, foreseeing worsening weather conditions, insisted on returning. On the way back, one of the Diomede Islands was discovered. Already in early September, "Saint Gabriel" reached the mouth of Kamchatka, where the travelers wintered. In June of the following year, Bering put to sea and headed straight east. So he thought to reach America. After passing about 200 km in dense fog and not meeting land, he turned back, rounded Kamchatka and arrived in Okhotsk. In two years, Bering with satellites surveyed more than 3,500 km of the coast.

In early March 1730, the expedition members returned to St. Petersburg. In the capital, Bering presented the materials of the voyage to the Admiralty Board - a magazine and maps. The final map of the expedition was widely used in Russia and abroad. Although it contains many errors (the outlines of Chukotka are distorted, the Gulf of Anadyr is too small, etc.), it is much more accurate and detailed than all the previous ones: it contains the islands of St. Lawrence and Diomede, the Kuril Islands, the coast of Kamchatka, and most importantly, the Chukotka Peninsula east is washed by water. As a result, this map became the basis for later maps by J. N. Delil, I. K. Kirilov, G. F. Miller, as well as the Academic Atlas (1745). James Cook, half a century later, following Bering's route along the coast of northeast Asia, noted the accuracy of the cartographic work carried out by the expedition.

However, her main goal - the American coast - was not achieved. Moreover, the Admiralty considered that the evidence presented by Bering for the absence of a land connection between the two continents was unconvincing. At the same time, he received the highest permission to lead a new expedition to the Pacific Ocean. By the way, in 1732, navigator Ivan Fedorov and surveyor Mikhail Gvozdev on the "St. Gabriel" again passed through the strait and made a map of it. Unlike Bering, they approached American soil - Cape Prince of Wales.

The sea in the North Pacific Ocean and the strait between Asia and America, at the suggestion of James Cook, were named after Bering, because Dezhnev's notes had been collecting dust in the Yakut archive for a long time. Maybe this is a kind of justice: Dezhnev discovered, but did not know what, and Bering did not discover, but he knew what he was looking for.

NUMBERS AND FACTS

Main character

Vitus Jonassen Behring, a Dane in Russian service

Other actors

Peter I, Russian emperor; Martin Spanberg and Alexei Chirikov, Bering's assistants; Ivan Fedorov, navigator; Mikhail Gvozdev, geodesist

Time of action

Route

Through all Russia to Okhotsk, by sea to Kamchatka, from there to the north, to the strait between Asia and America

Target

Find out if Asia and America connect, reach American shores

Meaning

Second passage of the Bering Strait, numerous discoveries, mapping of the coast of northeast Asia

Doctor of Historical Sciences V. Pasetsky.

Vitus Jonassen (Ivan Ivanovich) Bering A681-1741 years) belongs to the number of great navigators and polar explorers of the world. His name is given to the sea washing the shores of Kamchatka, Chukotka and Alaska, and the strait separating Asia from America.

Science and life // Illustrations

Science and life // Illustrations

Science and life // Illustrations

Science and life // Illustrations

Science and life // Illustrations

Science and life // Illustrations

Science and life // Illustrations

Bering was at the head of the greatest geographical enterprise, the equal of which the world did not know until the middle of the 20th century. The First and Second Kamchatka expeditions led by him covered the northern coast of Eurasia, all of Siberia, Kamchatka, the seas and lands of the northern Pacific Ocean, discovered the northwestern shores of America unknown to scientists and navigators.

The essay on the two Kamchatka expeditions of Vitus Bering, which we are publishing here, was written on the basis of documentary materials stored in the TsGAVMF (Central State Archive of the Navy). These are decrees and resolutions, personal diaries and scientific notes of the expedition members, ship's logs. Many of the materials used have never been published before.

Vitus Beriag was born on August 12, 1681 in Denmark, in the city of Horsens. He bore the name of his mother Anna Bering, who belonged to the famous Danish family. The navigator's father was a church warden. Almost no information has been preserved about Bering's childhood. It is known that as a young man he participated in a voyage to the shores of the East Indies, where he went even earlier and where his brother Sven spent many years.

Vitus Bering returned from his first trip in 1703. The ship on which he sailed arrived in Amsterdam. Here Bering met with the Russian admiral Kornely Ivanovich Kruys. On behalf of Peter I, Kruys hired experienced sailors for the Russian service. This meeting led Vitus Bering to serve in the Russian navy.

In St. Petersburg, Bering was appointed commander of a small ship. He delivered timber from the banks of the Neva to the island of Kotlin, where, by order of Peter I, a naval fortress was created - Kronstadt. In 1706, Bering was promoted to lieutenant. Many responsible assignments fell to his share: he followed the movements of Swedish ships in the Gulf of Finland, sailed in the Sea of \u200b\u200bAzov, ferried the Pearl ship from Hamburg to St. Petersburg, and made a trip from Arkhangelsk to Kronstadt around the Scandinavian Peninsula.

Twenty years have passed in labors and battles. And then came a sharp turn in his life.

On December 23, 1724, Peter I instructed the Admiralty Colleges to send an expedition to Kamchatka under the command of a worthy naval officer.

The Admiralty College proposed to put Captain Bering at the head of the expedition, since he "was in the East Indies and knows how to get around." Peter I agreed with Bering's candidacy.

On January 6, 1725, just a few weeks before his death, Peter signed the instructions for the First Kamchatka Expedition. Bering was ordered to build two deck ships in Kamchatka or in another suitable place. On these ships, it was necessary to go to the shores of the "land that goes to the north" and which, perhaps ("they do not know the end after it"), is part of America, that is, to determine whether the land going north really connects with America.

In addition to Bering, naval officers Aleksey Chirikov and Martyn Shpanberg, surveyors, navigators, ship masters were assigned to the expedition. A total of 34 people went on the trip.

Petersburg left in February 1725. The path lay through Vologda, Irkutsk, Yakutsk. This difficult campaign lasted for many weeks and months. Only at the end of 1726 did the expedition reach the shores of the Sea of Okhotsk.

The construction of the ship began immediately. The necessary materials were delivered from Yakutsk throughout the winter. This came with many difficulties.

On August 22, 1727, the newly built ship "Fortuna" and the small boat accompanying it left Okhotsk.

A week later, the travelers saw the shores of Kamchatka. Soon a strong leak opened in Fortuna. They were forced to go to the mouth of the Bolshaya River and unload the ships.

Bering's reports to the Admiralty Board, preserved in the Central State Archive of the Navy, give an idea of the difficulties that travelers encountered in Kamchatka, where they stayed for almost a year before they were able to set sail again, further to the North.

“... Upon arrival at the Bolsheretsky mouth,” Bering wrote, “materials and provisions were transported to the Bolsheretsky prison by water in small boats. With this prison of Russian housing there are 14 courtyards. And he sent heavy materials and some of the provisions up the Bystraya River in small boats, which were brought by water to the Upper Kamchadal prison for 120 miles. And in the same winter, from the Bolsheretsky prison to the Upper and Lower Kamchadal prisons, they were transported quite according to the local custom on dogs. And every evening on the way for the night they raked their camps out of the snow, and covered them from above, because the great blizzards live, which are called blizzards in the local language. And if a blizzard finds itself in a clean place, but they don’t have time to make a camp for themselves, then it covers people with snow, which is why they die.

On foot and on dog sleds they traveled more than 800 versts across Kamchatka to Nizhne-Kamchatsk. There was built a boat "St. Gabriel". On July 13, 1728, the expedition set sail again on it.

On August 11, they entered the strait that separates Asia from America and now bears the name of Bering. The next day, the sailors noticed that the land they had sailed past was left behind. On August 13, the ship, driven by strong winds, crossed the Arctic Circle.

Bering decided that the expedition had completed its task. He saw that the American coast did not connect with Asia, and he was convinced that there was no such connection further north.

On August 15, the expedition entered the open Arctic Ocean and continued to navigate in the fog to the north-northeast. Lots of whales appeared. The boundless ocean spread all around. The Chukotka land did not extend further north, according to Bering. Not approaching the "Chukotka corner" and America.

On the next day of sailing, there were no signs of the coast either in the west, or in the east, or in the north. Having reached 67 ° 18 "N, Bering gave the order to return to Kamchatka, so that "for no reason" not to spend the winter on unfamiliar treeless shores. On September 2, "St. Gabriel" returned to the Lower Kamchatka harbor. Here the expedition spent the winter.

As soon as the summer of 1729 came, Bering set sail again. He headed east, where, according to the inhabitants of Kamchatka, on clear days one could sometimes see land "across the sea". During the burden of last year's voyage, travelers "did not happen to see her." Berig decided to "be informed for sure" about whether this land really exists. Strong northerly winds were blowing. With great difficulty, the navigators traveled 200 kilometers, “but they didn’t see any land,” Bering wrote to the Admiralty College. The sea was enveloped in a "great fog", and with it a fierce storm began. They set a course for Okhotsk. On the way back, Bering for the first time in the history of navigation rounded and described the southern coast of Kamchatka.

On March 1, 1730, Bering, Lieutenant Shpanberg and Chirikov returned to St. Petersburg. Correspondence about the completion of Vitus Bering's First Kamchatka Expedition was published in Sankt-Peterburgskiye Vedomosti. It was reported that Russian navigators on ships built in Okhotsk and Kamchatka went up into the Polar Sea well north of 67°N. sh. and thereby proved ("invented") that "there is a truly north-eastern passage." Further, the newspaper emphasized: “Thus, from Lena, if ice did not interfere in the northern country, it would be possible to get to Kamchatka by water, and also further to Yapan, Khina and the East Indies, and besides, he (Bering.- V.P.) and from the local residents was informed that before 50 and 60 years a certain ship from Lena arrived in Kamchatka.

The first Kamchatka expedition made a major contribution to the development of geographical ideas about the northeastern coast of Asia, from Kamchatka to the northern coast of Chukotka. Geography, cartography and ethnography have been enriched with new valuable information. The expedition created a series of geographical maps, of which the final map is of particular importance. It is based on numerous astronomical observations and for the first time gave a real idea not only of the eastern coast of Russia, but also of the size and extent of Siberia. According to James Cook, who gave the Bering name to the strait between Asia and America, his distant predecessor "mapped the shores very well, determining the coordinates with an accuracy that, with his" capabilities, it would be difficult to expect. "The first map of the expedition, which shows the areas Siberia in the space from Tobolsk to the Pacific Ocean, was reviewed and approved by the Academy of Sciences. The final map was also immediately used by Russian scientists and soon spread widely in Europe. In 1735 it was engraved in Paris. A year later, published in London, then again in France And then this map was repeatedly republished as part of various atlases and books ... The expedition determined the coordinates of 28 points along the route Tobolsk - Yeniseisk - Ilimsk - Yakutsk - Okhotsk-Kamchatka-Chukotsky Nose-Chukotskoye Sea, which were then included in the "Catalogue of cities and noble Siberian places, put on the map, through which they had a path, in what width and length they are.

And Bering was already developing a project for the Second Kamchatka Expedition, which later turned into an outstanding geographical enterprise, the equal of which the world had not known for a long time.

The leading place in the program of the expedition, headed by Bering, was given to the study of all of Siberia, the Far East, the Arctic, Japan, northwestern America in geographical, geological, physical, botanical, zoological, ethnographic terms. Particular importance was attached to the study of the Northern Sea Passage from Arkhangelsk to the Pacific Ocean.

At the beginning of 1733, the main detachments of the expedition left St. Petersburg. More than 500 naval officers, scientists and sailors were sent from the capital to Siberia.

Bering, together with his wife Anna Matveevna, went to Yakutsk to manage the transfer of cargo to the port of Okhotsk, where five ships were to be built to sail the Pacific Ocean. Bering followed the work of the detachments of X. and D. Laptev, D. Ovtsyn, V. Pronchishchev, P. Lassinius, who were engaged in the study of the northern coast of Russia, and the academic detachment, which included historians G. Miller and A. Fisher, naturalists I. Gmelin, S. Krasheninnikov, G. Steller, astronomer L. Delacroer.

Archival documents give an idea of the unusually active and versatile organizational work of the navigator, who led from Yakutsk the activities of many detachments and units of the expedition, which conducted research from the Urals to the Pacific Ocean and from the Amur to the northern coast of Siberia.

In 1740, the construction of the St. Peter" and "St. Pavel", on which Vitus Bering and Aleksey Chirikov undertook a transition to the Avacha harbor, on the shore of which the Peter and Paul port was laid.

152 officers and sailors and two members of the academic detachment went on a voyage on two ships. Professor L. Delacroer Bering identified the ship "St. Pavel”, and took adjunct G. Steller to “St. Peter" to his crew. Thus began the path of a scientist who later gained worldwide fame.

On June 4, 1741, the ships put to sea. They headed southeast, to the shores of the hypothetical Land of Juan de Gama, which was listed on the map of J. N. Delil and which was ordered to be found and explored on the way to the shores of northwestern America. Severe storms hit the ships, but Bering persistently walked forward, trying to accurately fulfill the decree of the Senate. There was often fog. In order not to lose a friend of a friend, the ships rang the bell or fired cannons. Thus passed the first week of sailing. The ships reached 47°N. sh., where the Land of Juan de Gama was supposed to be, but there were no signs of land. On June 12, the travelers crossed the next parallel - no land. Bering ordered to go to the northeast. He considered his main task to reach the northwestern shores of America, which had not yet been discovered and explored by any navigator.

As soon as the ships passed the first tens of miles to the north, they found themselves in thick fog. Packet boat "St. Pavel "under the command of Chirikov disappeared from sight. For several hours they could hear the bell being struck there, letting them know their whereabouts, then the bells were not heard, and a deep silence lay over the ocean. Captain-Commander Bering ordered the cannon to be fired. There was no answer.

For three days, Bering plowed the sea, as agreed, in those latitudes where the ships parted, but did not meet the detachment of Alexei Chirikov.

For about four weeks, the packet boat "St. Peter" walked the ocean, meeting only herds of whales along the way. All this time, storms mercilessly battered a lonely ship. The storms followed one after another. The wind tore the sails, damaged the spars, loosened the fasteners. There was a leak somewhere in the grooves. The fresh water we brought with us was running out.

“July 17,” as recorded in the logbook, “from noon at half past one we saw land with high ridges and a hill covered with snow.”

Bering and his companions were impatient to quickly land on the American coast they had discovered. But strong winds were blowing. The expedition, fearing stone reefs, was forced to stay away from the land and follow along it to the west. Only on July 20 did the excitement decrease, and the sailors decided to lower the boat.

Bering sent the naturalist Steller to the island. Steller spent 10 hours on the coast of Kayak Island and during this time managed to get acquainted with the abandoned dwellings of the Indians, their household items, weapons and clothing remnants, described 160 species of local plants.

End of July to August “St. Peter "walked either in the labyrinth of islands, or at a small distance from them.

On August 29, the expedition approached the land again and anchored between several islands, which were named Shumaginsky after the sailor Shumagin, who had just died of scurvy. Here the travelers first met the inhabitants of the Aleutian Islands and exchanged gifts with them.

September came, the ocean stormed. The wooden ship could hardly withstand the onslaught of the hurricane. Many officers began to talk about the need to stay for the winter, especially since the air was getting colder.

The travelers decided to rush to the shores of Kamchatka. More and more alarming entries appear in the logbook, testifying to the difficult situation of the navigators. The yellowed pages, hastily written by duty officers, speak of how they sailed day after day without seeing the land. The sky was covered with clouds, through which for many days no sunbeam broke through and not a single star was visible. The expedition could not accurately determine its location and did not know how fast they were moving towards their native Petropavlovsk...

Vitus Bering was seriously ill. The disease was further aggravated by dampness and cold. It rained almost continuously. The situation became more and more serious. According to the captain's calculations, the expedition was still far from Kamchatka. He understood that he would not reach his native promised land until the end of October, and this only if the western winds changed to favorable eastern ones.

On September 27, a fierce squall hit, and three days later a storm broke out, which, as noted in the logbook, spread "great excitement." Only four days later the wind decreased somewhat. The respite was short-lived. On October 4, a new hurricane hit, and huge waves again fell on the sides of the St. Peter."

Since the beginning of October, most of the crew had already become so weak from scurvy that they could not take part in shipboard work. Many lost their arms and legs. Stocks of provisions were disastrously melting ...

Having endured a severe multi-day storm, “St. Peter" began to move forward again, despite the oncoming west wind, and soon the expedition discovered three islands: St. Markian, St. Stephen and St. Abraham.

The dramatic situation of the expedition was aggravated every day. Not only food was lacking, but also fresh water. The officers and sailors, who were still on their feet, were exhausted by overwork. According to navigator Sven Waxel, "the ship sailed like a piece of dead wood, almost without any control and went at the behest of the waves and wind, wherever they only decided to drive it."

On October 24, the first snow covered the deck, but, fortunately, did not last long. The air became more and more cold. On this day, as noted in the watch log, there were "28 people of various ranks" who were sick.

Bering understood that the most crucial and difficult moment had come in the fate of the expedition. Himself, completely exhausted by the disease, he nevertheless went up on deck, visited the officers and sailors, tried to raise faith in a successful outcome of the journey. Bering promised that as soon as land appeared on the horizon, they would certainly moor to it and stop for the winter. Team "St. Petra "trusted her captain, and everyone who could move their legs, straining their last strength, corrected urgent and necessary ship work.

On November 4, early in the morning, the contours of an unknown land appeared on the horizon. Having approached it, they sent officer Plenisner and naturalist Steller ashore. There they found only thickets of dwarf willow, creeping along the ground. Not a single tree grew anywhere. In some places on the shore lay logs thrown out by the sea and covered with snow.

A small river flowed nearby. In the vicinity of the bay, several deep pits were found, which, if covered with sails, can be adapted for housing for sick sailors and officers.

The landing has begun. Bering was transferred on a stretcher to a dugout prepared for him.

The landing was slow. Hungry sailors, weakened by illness, died on the way from ship to shore or barely set foot on land. So 9 people died, 12 sailors died during the voyage.

On November 28, a strong storm tore the ship off the anchors and threw it ashore. At first, the sailors did not attach any serious importance to this, since they believed that they had landed on Kamchatka, that the locals would help the pits on dogs to get to Petropavlovsk.

The group sent by Bering for reconnaissance climbed to the top of the mountain. From above, they saw that a boundless sea spread around them. They landed not in Kamchatka, but on an uninhabited island lost in the ocean.

“This news,” wrote Svey Waxel, “acted on our people like a thunderclap. We clearly understood what a helpless and difficult situation I was in, that we were in danger of complete destruction.

In these difficult days, the illness tormented Bering more and more. He felt that his days were numbered, but he continued to take care of his people.

The captain-commander was lying alone in a dugout covered with a tarpaulin on top. Bering suffered from a cold. The strength left him. He could no longer move his arm or leg. Sand sliding down from the walls of the dugout covered the legs and lower part of the body. When the officers wanted to dig it up, Bering objected, saying that it was warmer that way. In these last, most difficult days, despite all the misfortunes that befell the expedition, Bering did not lose his good spirits, he found sincere words to encourage his despondent comrades.

Bering died on December 8, 1741, unaware that the last refuge of the expedition was a few days of good ship progress from Petropavlovsk.

Bering's satellites survived a hard winter. They ate the meat of marine animals, which were found here in abundance. Under the leadership of officers Sven Waxel and Sofron Khitrovo, they built a new ship from the wreckage of the St. Peter". On August 13, 1742, the travelers said goodbye to the island, which was named after Bering, and safely reached Petropavlovsk. There they learned that the packet boat "St. Pavel, commanded by Alexei Chirikov, returned to Kamchatka last year, having discovered, like I Bering, the northwestern shores of America. These lands were soon called Russian America (now Alaska).

Thus ended the Second Kamchatka Expedition, whose activity was crowned with great discoveries and outstanding scientific achievements.

Russian sailors were the first to discover the previously unknown northwestern shores of America, the Aleutian ridge, the Commander Islands and crossed out the myths about the Land of Juan de Gama, which Western European cartographers depicted in the North Pacific Ocean.

Russian ships were the first to pave the sea route from Russia to Japan. Geographical science received accurate information about the Kuril Islands, about Japan.

The results of discoveries and research in the northern part of the Pacific Ocean are reflected in a series of maps. Many of the surviving members of the expedition took part in their creation. A particularly prominent role in summarizing the materials obtained by Russian sailors belongs to Alexei Chirikov, one of the brilliant and skillful sailors of that time, Bering's devoted assistant and successor. It fell to Chirikov to complete the affairs of the Second Kamchatka Expedition. He compiled a map of the North Pacific Ocean, which shows with amazing accuracy the path of the ship "St. Pavel”, the northwestern shores of America discovered by sailors, the islands of the Aleutian ridge and the eastern shores of Kamchatka, which served as the starting base for Russian expeditions.

Officers Dmitry Ovtsyn, Sofron Khitrovo, Alexei Chirikov, Ivan Elagin, Stepan Malygin, Dmitry and Khariton Laptev compiled a “Map of the Russian Empire, the northern and eastern shores adjacent to the Arctic and Eastern Oceans with a part of the western American coasts and islands newly found through sea navigation Japan".

Equally fruitful was the activity of the northern detachments of the Second Kamchatka Expedition, often separated into an independent Great Northern Expedition.

As a result of sea and foot campaigns of officers, navigators and surveyors operating in the Arctic, the northern coast of Russia from Arkhangelsk to Bolshoy Baranov Kamen, located east of Kolyma, was explored and mapped. Thus, according to M. V. Lomonosov, “the passage of the sea from the Arctic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean was undoubtedly proved.”

To study the meteorological conditions of Siberia, observation posts were established from the Volga to Kamchatka. The world's first experience in organizing a meteorological network over such a vast area was a brilliant success for Russian scientists and sailors.

Visual and, in some cases, instrumental meteorological observations were carried out on all ships of the Second Kamchatka Expedition, which sailed through the polar seas from Arkhangelsk to Kolyma, across the Pacific Ocean to Japan and northwestern America. They are included in logbooks and have survived to this day. Today, these observations are of particular value also because they reflect the features of atmospheric processes in the years of extremely high ice cover in the Arctic seas.

The scientific heritage of the Second Kamchatka Expedition of Vitus Bering is so great that it has not been fully mastered so far. It was used and is now widely used by scientists in many countries.