Gilgamesh king of Uruk. Myths and legends. The biblical flood in the legend of Ancient Sumer

Left a reply Guest

Gilgamesh is a real historical person who lived at the end of the 27th - beginning of the 26th century. BC e. Gilgamesh was the ruler of the city of Uruk in Sumer. He began to be considered a deity only after his death. It was said that he was two-thirds god, only one-third man, and reigned for almost 126 years.

At first his name sounded different. The Sumerian version of his name, according to historians, comes from the form “Bilge - mes”, which means “ancestor - hero”. Strong, brave, decisive, Gilgamesh was distinguished by his enormous height and loved military fun. The inhabitants of Uruk turned to the gods and asked to pacify the militant Gilgamesh. Then the gods created the wild man Enkidu, thinking that he could quench the giant. Enkidu entered into a duel with Gilgamesh, but the heroes quickly found out they were of equal strength. They became friends and accomplished many glorious deeds together.

One day they went to the land of cedar. In this distant country, on the top of a mountain lived the evil giant Huwawa. He caused a lot of harm to people. The heroes defeated the giant and cut off his head. But the gods were angry with them for such insolence and, on the advice of Inanna, sent an amazing bull to Uruk. Inanna had long been very angry with Gilgamesh for remaining indifferent to her, despite all her signs of respect. But Gilgamesh, together with Enkidu, killed the bull, which angered the gods even more. To take revenge on the hero, the gods killed his friend.

Enkidu - This was the most terrible disaster for Gilgamesh. After the death of his friend, Gilgamesh went to find out the secret of immortality from the immortal man Ut-Napishtim. He told the guest about how he survived the Flood. He told him that it was precisely for his persistence in overcoming difficulties that the gods gave him eternal life. The immortal man knew that the gods would not hold a council for Gilgamesh. But, wanting to help the unfortunate hero, he revealed to him the secret of the flower of eternal youth. Gilgamesh managed to find the mysterious flower. And at that moment, when he tried to pick it, a snake grabbed the flower and immediately became a young snake. Gilgamesh, upset, returned to Uruk. But the sight of a prosperous and well-fortified city pleased him. The people of Uruk were glad to see him return.

The legend of Gilgamesh tells of the futility of man's attempts to achieve immortality. A person can become immortal only in the memory of people if they tell about her good deeds and exploits to their children and grandchildren.

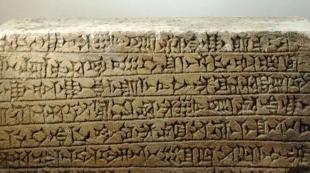

The epic (from the gr. “Word, narrative, story”) about Gilgamesh was written down on clay tablets for 2500 BC. Five epic songs about Gilgamesh have been preserved, telling about his heroic adventures.

Epic texts consider Gilgamesh to be the son of the hero Lugalbanda and the goddess Ninsun. The “Royal List” from Nippur - a list of the dynasties of Mesopotamia - dates the reign of Gilgamesh to the era of the First Dynasty of Uruk (27–26 centuries BC). Gilgamesh is the fifth king of this dynasty, whose name follows those of Lugalbanda and Dumuzi, the consort of the goddess Inanna. Gilgamesh is also attributed divine origin: "Bilgames, whose father was the demon-lila, en (i.e., "high priest") of Kulaba." The duration of Gilgamesh's reign is determined by the "Royal List" to be 126 years.

The Sumerian tradition places Gilgamesh as if on the border between the legendary heroic time and the more recent historical past. Starting with the son of Gilgamesh, the length of the years of reign of the kings in the “Royal List” becomes closer to the terms of human life. The names of Gilgamesh and his son Ur-Nungal are mentioned in the inscription of the general Sumerian sanctuary of Tummal in Nippur among the rulers who built and rebuilt the temple.

During the First Dynasty, Uruk was surrounded by a 9 km long wall, the construction of which is associated with the name of King Gilgamesh. Five Sumerian heroic tales recount the deeds of Gilgamesh. One of them - “Gilgamesh and Agga” - reflects real events of the late 27th century. BC e. and talks about the victory won by the king over the army of the city of Kish that besieged Uruk.

In the tale “Gilgamesh and the Mountain of the Immortal,” the hero leads the youths of Uruk into the mountains, where they cut down evergreen cedars and defeat the monster Humababu. The poorly preserved cuneiform text “Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven” tells of the hero’s struggle with the bull sent by the goddess Inanna to destroy Uruk. The text "The Death of Gilgamesh" is also presented only in fragments. The legend “Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the Underworld” reflects the cosmogonic ideas of the Sumerians. It has a complex composition and is divided into a number of separate episodes.

In the ancient days of the beginning of the world, a huluppu tree was planted in Inanna’s garden, from which the goddess wanted to make her throne. But the bird Anzud hatched a chick in its branches, the demon maiden Lilith settled in the trunk, and a snake began to live under the root. In response to Inanna's complaints, Gilgamesh defeated them, cut down a tree and made from it a throne, a bed for the goddess and magical objects “pucca” and “mikku” - musical instruments, the loud sound of which made the young men of Uruk dance tirelessly. The curses of the women of the city, disturbed by the noise, led to the fact that “pukku” and “mikku” fell underground and remained lying at the entrance to the underworld. Enkidu, Gilgamesh's servant, volunteered to get them, but violated magical prohibitions and was left in the kingdom of the dead. Heeding Gilgamesh's pleas, the gods opened the entrance to the underworld and Enkidu's spirit came out. In the last surviving episode, Enkidu answers Gilgamesh's questions about the laws of the kingdom of the dead. The Sumerian tales of Gilgamesh are part of an ancient tradition that is closely related to oral tradition and has parallels with fairy tales of other peoples.

The motifs of the heroic tales of Gilgamesh and Enkidu were reinterpreted in the literary monument of the Ancient East - the Akkkadian “Epic of Gilgamesh”. The epic survives in three main versions. This is a Nineveh version from the library of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal, dating back to the second half of 2 thousand BC. e.; the contemporary so-called peripheral version, represented by the Hittite-Hurrian poem about Gilgamesh, and the most ancient of all, the Old Babylonian version.

The Nineveh version, according to tradition, was written down “from the mouth” of the Uruk spellcaster Sin-leke-uninni; its fragments were also found in Ashur, Uruk and Sultan-tepe. When reconstructing the epic, all published fragments are taken into account; unpreserved lines of one text can be filled in from other versions of the poem. The Epic of Gilgamesh is written on 12 clay tablets; the last of them is compositionally unrelated to the main text and is a literal translation into Akkadian of the last part of the tale of Gilgamesh and the Huluppu tree.

Table I tells about the king of Uruk, Gilgamesh, whose unbridled prowess caused a lot of grief to the inhabitants of the city. Having decided to create a worthy rival and friend for him, the gods molded Enkidu from clay and settled him among wild animals. Table II is devoted to the martial arts of the heroes and their decision to use their powers for good, cutting down a precious cedar in the mountains. Tables III, IV and V are devoted to their preparations for the road, travel and victory over Humbaba. Table VI is close in content to the Sumerian text about Gilgamesh and the celestial bull. Gilgamesh rejects Inanna's love and reproaches her for her treachery. Insulted, Inanna asks the gods to create a monstrous bull to destroy Uruk. Gilgamesh and Enkidu kill a bull; Unable to take revenge on Gilgamesh, Inanna transfers her anger to Enkidu, who weakens and dies.

The story of his farewell to life (VII table) and Gilgamesh’s cry for Enkidu (VIII table) become the turning point of the epic tale. Shocked by the death of his friend, the hero sets out in search of immortality. His wanderings are described in Tables IX and X. Gilgamesh wanders in the desert and reaches the Mashu Mountains, where scorpion men guard the passage through which the sun rises and sets. “Mistress of the Gods” Siduri helps Gilgamesh find the shipbuilder Urshanabi, who ferried him across the “waters of death” that are fatal to humans. On the opposite shore of the sea, Gilgamesh meets Utnapishtim and his wife, to whom in time immemorial the gods gave eternal life.

Table XI contains the famous story about the Flood and the construction of the ark, on which Utnapishtim saved the human race from extermination. Utnapishtim proves to Gilgamesh that his search for immortality is futile, since man is unable to defeat even the semblance of death - sleep. In parting, he reveals to the hero the secret of the “grass of immortality” growing at the bottom of the sea. Gilgamesh obtains the herb and decides to bring it to Uruk to give immortality to all people. On the way back, the hero falls asleep at the source; a snake rising from its depths eats the grass, sheds its skin and, as it were, receives a second life. The text of Table XI known to us ends with a description of how Gilgamesh shows Urshanabi the walls of Uruk he erected, hoping that his deeds will be preserved in the memory of his descendants.

As the plot of the epic develops, the image of Gilgamesh changes. The fairy-tale hero-hero, boasting of his strength, turns into a man who has learned the tragic brevity of life. The powerful spirit of Gilgamesh rebels against the recognition of the inevitability of death; only at the end of his wanderings does the hero begin to understand that immortality can bring him eternal glory to his name.

Gilgamesh Gilgamesh

semi-legendary ruler of the city of Uruk in Sumer (XXVII-XXVI centuries BC). In the Sumerian epic songs of the 3rd millennium BC. e. and a large poem from the end of the 3rd - beginning of the 2nd millennium BC. e. describes, in particular, the wanderings of Gilgamesh in search of the secret of immortality. The legend of Gilgamesh also spread among the Hittites, Hurrians, and others.

GILGAMESHGILGAMESH (Sumerian. Bilga-mes - this name can be interpreted as “hero ancestor”), semi-legendary ruler of Uruk (cm. URUK), hero of the epic tradition of Sumer (cm. SUMER) and Akkad (cm. AKKAD (state)). Epic texts consider Gilgamesh to be the son of the hero Lugalbanda (cm. LUGALBANDA) and the goddess Ninsun. "Royal List" from Nippur (cm. NIPPUR)- list of dynasties of Mesopotamia - dates the reign of Gilgamesh to the era of the First Dynasty of Uruk (27–26 centuries BC). Gilgamesh is the fifth king of this dynasty, whose name follows those of Lugalbanda and Dumuzi (cm. DUMUZI), wife of the goddess Inanna (cm. INANNA). Gilgamesh is also attributed divine origin: "Bilgames, whose father was the demon-lila, en (i.e., "high priest") of Kulaba." The duration of Gilgamesh's reign is determined by the "Royal List" to be 126 years.

The Sumerian tradition places Gilgamesh as if on the border between the legendary heroic time and the more recent historical past. Starting with the son of Gilgamesh, the length of the years of reign of the kings in the “Royal List” becomes closer to the terms of human life. The names of Gilgamesh and his son Ur-Nungal are mentioned in the inscription of the general Sumerian sanctuary of Tummal in Nippur among the rulers who built and rebuilt the temple.

During the First Dynasty, Uruk was surrounded by a 9 km long wall, the construction of which is associated with the name of King Gilgamesh. Five Sumerian heroic tales recount the deeds of Gilgamesh. One of them - “Gilgamesh and Agga” - reflects real events of the late 27th century. BC e. and talks about the victory won by the king over the army of the city of Kish that besieged Uruk (cm. KISH (Mesopotamia)).

In the tale “Gilgamesh and the Mountain of the Immortal,” the hero leads the youths of Uruk into the mountains, where they cut down evergreen cedars and defeat the monster Humababu. The poorly preserved cuneiform text “Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven” tells of the hero’s struggle with the bull sent by the goddess Inanna to destroy Uruk. The text "The Death of Gilgamesh" is also presented only in fragments. The legend “Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the Underworld” reflects the cosmogonic ideas of the Sumerians. It has a complex composition and is divided into a number of separate episodes.

In the ancient days of the beginning of the world, a huluppu tree was planted in Inanna’s garden, from which the goddess wanted to make her throne. But in its branches the bird Anzud hatched a chick (cm. ANZUD), the demon maiden Lilith settled in the trunk, and a snake began to live under the root. In response to Inanna's complaints, Gilgamesh defeated them, cut down a tree and made from it a throne, a bed for the goddess and magical objects “pucca” and “mikku” - musical instruments, the loud sound of which made the young men of Uruk dance tirelessly. The curses of the women of the city, disturbed by the noise, led to the fact that “pukku” and “mikku” fell underground and remained lying at the entrance to the underworld. Enkidu, Gilgamesh's servant, volunteered to get them, but violated magical prohibitions and was left in the kingdom of the dead. Heeding Gilgamesh's pleas, the gods opened the entrance to the underworld and Enkidu's spirit came out. In the last surviving episode, Enkidu answers Gilgamesh's questions about the laws of the kingdom of the dead. The Sumerian tales of Gilgamesh are part of an ancient tradition that is closely related to oral tradition and has parallels with fairy tales of other peoples.

The motifs of the heroic tales of Gilgamesh and Enkidu were reinterpreted in the literary monument of the Ancient East - the Akkkadian “Epic of Gilgamesh”. The epic survives in three main versions. This is the Nineveh version from the library of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (cm. ASSHURBANIPAL), dating back to the second half of 2 thousand BC. e.; the contemporary so-called peripheral version, represented by the Hittite-Hurrian poem about Gilgamesh, and the most ancient of all, the Old Babylonian version.

The Nineveh version, according to tradition, was written down “from the mouth” of the Uruk spellcaster Sin-leke-uninni; its fragments were also found in Ashur, Uruk and Sultan-tepe. When reconstructing the epic, all published fragments are taken into account; unpreserved lines of one text can be filled in from other versions of the poem. The Epic of Gilgamesh is written on 12 clay tablets; the last of them is compositionally unrelated to the main text and is a literal translation into Akkadian of the last part of the tale of Gilgamesh and the Huluppu tree.

Table I tells about the king of Uruk, Gilgamesh, whose unbridled prowess caused a lot of grief to the inhabitants of the city. Having decided to create a worthy rival and friend for him, the gods molded Enkidu from clay and settled him among wild animals. Table II is devoted to the martial arts of the heroes and their decision to use their powers for good, cutting down a precious cedar in the mountains. Tables III, IV and V are devoted to their preparations for the road, travel and victory over Humbaba. Table VI is close in content to the Sumerian text about Gilgamesh and the celestial bull. Gilgamesh rejects Inanna's love and reproaches her for her treachery. Insulted, Inanna asks the gods to create a monstrous bull to destroy Uruk. Gilgamesh and Enkidu kill a bull; Unable to take revenge on Gilgamesh, Inanna transfers her anger to Enkidu, who weakens and dies.

The story of his farewell to life (VII table) and Gilgamesh’s cry for Enkidu (VIII table) become the turning point of the epic tale. Shocked by the death of his friend, the hero sets out in search of immortality. His wanderings are described in Tables IX and X. Gilgamesh wanders in the desert and reaches the Mashu Mountains, where scorpion men guard the passage through which the sun rises and sets. “Mistress of the Gods” Siduri helps Gilgamesh find the shipbuilder Urshanabi, who ferried him across the “waters of death” that are fatal to humans. On the opposite shore of the sea, Gilgamesh meets Utnapishtim and his wife, to whom in time immemorial the gods gave eternal life.

Table XI contains the famous story about the Flood and the construction of the ark, on which Utnapishtim saved the human race from extermination. Utnapishtim proves to Gilgamesh that his search for immortality is futile, since man is unable to defeat even the semblance of death - sleep. In parting, he reveals to the hero the secret of the “grass of immortality” growing at the bottom of the sea. Gilgamesh obtains the herb and decides to bring it to Uruk to give immortality to all people. On the way back, the hero falls asleep at the source; a snake rising from its depths eats the grass, sheds its skin and, as it were, receives a second life. The text of Table XI known to us ends with a description of how Gilgamesh shows Urshanabi the walls of Uruk he erected, hoping that his deeds will be preserved in the memory of his descendants.

As the plot of the epic develops, the image of Gilgamesh changes. The fairy-tale hero-hero, boasting of his strength, turns into a man who has learned the tragic brevity of life. The powerful spirit of Gilgamesh rebels against the recognition of the inevitability of death; only at the end of his wanderings does the hero begin to understand that immortality can bring him eternal glory to his name.

The history of the opening of the epic in the 1870s is associated with the name of George Smith (cm. SMITH George), an employee of the British Museum, who, among the extensive archaeological materials sent to London from Mesopotamia, discovered cuneiform fragments of the legend of the Flood. A report on this discovery, made at the end of 1872 by the Biblical Archaeological Society, created a sensation; Seeking to prove the authenticity of his find, Smith went to the excavation site in Nineveh in 1873 and found new fragments of cuneiform tablets. J. Smith died in 1876 in the midst of work on cuneiform texts during his third trip to Mesopotamia, bequeathing in his diaries to subsequent generations of researchers to continue the study of the epic he had begun. The Epic of Gilgamesh was translated into Russian at the beginning of the 20th century. V. K. Shileiko and N. S. Gumilyov (cm. GUMILEV Nikolay Stepanovich). A scientific translation of the text, accompanied by detailed comments, was published in 1961 by I. M. Dyakonov (cm. DYAKONOV Igor Mikhailovich).

encyclopedic Dictionary. 2009 .

Synonyms:See what "Gilgamesh" is in other dictionaries:

Gilgamesh ... Wikipedia

Sumerian and Akkadian mythoepic hero (G. Akkadian name; the Sumerian version apparently goes back to the form Bilha mes, which possibly means “ancestor hero”). A number of texts published in recent decades allow us to consider G. real... ... Encyclopedia of Mythology

Gilgamesh- Gilgamesh. 8th century BC. Louvre. Gilgamesh. 8th century BC. Louvre. Gilgamesh is the semi-legendary ruler of the 1st dynasty of the city of Uruk in Sumer (BC), the hero of Sumerian myths. He is credited with reigning for 126 years; was distinguished by his masculinity, enormous... Encyclopedic Dictionary of World History

Semi-legendary ruler of the city of Uruk in Sumer (27-26 centuries BC). In the Sumerian epic songs of the 3rd millennium BC. e. and the great poem con. 3rd beginning 2nd millennium BC e. describes Gilgamesh's friendship with the wild man Enkidu, Gilgamesh's wanderings in... Big Encyclopedic Dictionary

Noun, number of synonyms: 1 heroine (17) ASIS Dictionary of Synonyms. V.N. Trishin. 2013… Synonym dictionary

Gilgamesh- (Gilgamesh), the legendary ruler of the Sumerian city of the state of Uruk in the South. Mesopotamia ca. 1st half of 3 thousand BC and the hero of the epic of the same name, one of the most famous lit. works of Dr. East. The epic tells about G.’s attempts to achieve... ... The World History

GILGAMESH- Sumerian and Akkadian mythological hero. G. Akkad. name, Sumerian the variant seems to go back to the form Bil ha mes, which may have meant "ancestor hero". Research conducted in recent decades allows us to consider G. a real historical... ... Orthodox Encyclopedia

Semi-legendary ruler of the city of Uruk in Sumer (28th century BC). In the 3rd millennium BC. e. Sumerian epic songs about God that have come down to us arose. At the end of the 3rd beginning of the 2nd millennium, a large ... ... Great Soviet Encyclopedia

It is the shortest Sumerian epic poem and contains no mention of any gods. Apparently, this legend can be considered as a historiographical text. Tablets with this myth were found by an expedition of the University of Pennsylvania in Nippur and date back to the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC, possibly being copies of earlier Sumerian texts.

Agga was the last ruler of the 1st Dynasty of Kish, which dominated Sumer after the flood. Seeing the rise of Uruk, where Gilgamesh ruled, Agga sent envoys there demanding that the inhabitants of Uruk be sent for construction work in Kish. Gilgamesh turned to the council of elders of his city and they recommended submission. Then the disappointed Gilgamesh goes to a meeting of the “men of the city” and they support his desire to free himself from the hegemony of Kish. The ruler of Uruk refused the ambassadors.

Soon, “it wasn’t five days, it wasn’t ten days,” Agga besieged Uruk. Despite the incendiary speeches, fear settles in the hearts of the city's residents. Then Gilgamesh, turning to the heroes of the city, asks them to go beyond the fortifications and fight the king of Kish. The chief councilor Birhurturre (Girishhurturre) responds to his call, but as soon as he leaves the gate, he is captured, tortured and brought to Agga. The ruler of Kish starts a conversation with him. Here another hero Zabardibunug climbs the wall. Seeing him, Agga asks Birhurturre if this is Gilgamesh. He gives a negative answer and the people of Kish continue to torture Birhurturre.

Now Gilgamesh himself climbs the wall and all of Uruk freezes in horror. Having learned from Birhurturre that this is the ruler of Uruk, Agga holds back the troops who are ready to rush into battle.

Gilgamesh expresses his gratitude to Agga and the poem ends with the praise of the savior of Uruk, the ruler of Gilgamesh.

Ambassadors of Aga, son of En-Mebaragesi,

From Kish to Uruk they came to Gilgamesh.

Gilgamesh before the elders of his city

The Word speaks, the words seek them:

"So that we can dig wells,

Dig all the wells in the country,

Meeting of the Elders of the City of Uruk

Answers Gilgamesh:

"So that we can dig wells,

Dig all the wells in the country,

Big and small in the country to dig,

To complete the work, attach the bucket with a rope,

We will bow our heads before Kish, we will not defeat Kish with weapons!”

He trusts in Inanna,

I did not accept the words of the elders with my heart.

And the second time Gilgamesh, priest of Kulab,

He speaks the word before the men of the city, seeks their words:

"So that we can dig wells,

Dig all the wells in the country.

Big and small in the country to dig,

To complete the work, attach the bucket with a rope,

Don’t bow your head before Kish, strike Kish with weapons!”

Meeting of the Men of Uruk

Answers Gilgamesh:

"O those who stand, O those who sit!

Those who follow the military leader!

The donkey's sides are squeezing!

Who breathes to protect the city? -

We will not bow our heads before Kish, we will defeat Kish with weapons!”

Uruk is God's work,

Eanna - a temple that descended from heaven:

Great gods created it!

The Great Wall - the touch of menacing clouds,

From now on, you are the guardian, the military leader-leader!

From now on, you are the warrior, Anom’s beloved prince!

How can you be afraid of Aga?

Agha's army is small, its ranks are thinning,

People don’t dare raise their eyes!”

Then Gilgamesh, priest of Kulab, -

How my heart leaped at the speeches of the soldiers,

The liver rejoiced! -

He says to his servant Enkidu:

“Now the ax will replace the hoe!

The weapon of war will return to your thigh,

You will cover it with the radiance of glory!

And Agu, when he comes out, he will cover my radiance!

And there are not five days, and there are not ten days,

And Aga, the son of En-Mebaragesi, is on the outskirts of Uruk.

Uruk's thoughts are confused,

Gilgamesh, High Priest of Kulab,

To his valiant men he says a word:

"My heroes! My sharp-eyed ones!

Let the brave one rise up and go to Are!”

Girishkhurtura, chief adviser to the leader,

He praises his leader!

"Truly I will go to Are!

May his thoughts be confused, his mind clouded!”

Girishkhurtura comes out of the main gate.

Girishkhurturu at the main gate, upon exit,

On leaving the main gate they grabbed me.

They torture Girishkhurtura's body.

They bring him to Are.

He addresses Are.

He speaks, and the handsome Uruk climbs the wall.

He hung his head over the wall.

Yeah I noticed him there

Girishhurture says:

"This husband is not my leader!

For my leader is truly a husband!

His brow is menacing, truly so!

The anger of the tour is in the eyes, truly so!

The beard is lapis lazuli, truly so!

Grace is in the fingers, truly so!

Wouldn't he have brought down people, wouldn't he have lifted people up?

Wouldn't he mix people up with dust?

Wouldn't you crush hostile countries?

Wouldn’t you cover the “mouth of the earth” with ashes?

Wouldn't you cut off the loaded bow of a boat?

Agu, the leader of Kish, would not have taken him prisoner among the army?

They beat him, they tear him,

They torture the body of Girishkhurtura,

Following the handsome Uruk, Gilgamesh climbed the wall.

His radiance fell on the small and old of Kulaba.

The warriors of Uruk grabbed their weapons,

They stood at the city gates and in the alleys.

Enkidu walked out of the city gates.

Gilgamesh hung his head over the wall.

Yeah I noticed him there.

“Servant! Is this husband your leader?”

"This husband is my leader!

It’s truly said, truly so!”

He brought down people, he lifted up people,

He mixed people with dust,

He crushed hostile countries,

He covered the “mouth of the earth” with ashes,

The rooks are loaded with a bow compartment,

Agu, the leader of Kish, took him prisoner among the army.

Gilgamesh, High Priest of Kulab,

Addresses to Are:

“Aga is my headman, Aga is my work supervisor!

Yeah - the boss of my troops!

Yeah, you feed the runaway bird grain!

Yeah, you're bringing fugitives home!

Aha, you gave me back my breath, Aha, you gave me my life back!”

"Uruk is God's work!

The Great Wall - the touch of menacing clouds -

The buildings of the mighty are the creation of heavenly steeps, -

You are the guardian, the leader-leader

Warrior, Anom's beloved prince!

Pred Utu regained his former strength,

He freed Aga for Kish!

O Gilgamesh, high priest of Kulab,

A good song of praise for you!”

A brave, fearless demigod named Gilgamesh became famous thanks to his own exploits, love for women and ability to be friends with men. The rebel and ruler of the Sumerians lived to be 126 years old. True, nothing is known about the death of the brave warrior. Perhaps the fame of his deeds does not embellish the reality, and the brave Gilgamesh found a way to achieve the immortality that he so persistently sought.

History of creation

The biography of Gilgamesh has reached the modern world thanks to cuneiform writing called “The Epic of Gilgamesh” (another name is “Of the One Who Has Seen All”). The literary work contains scattered legends telling about the exploits of an ambiguous character. Some of the records included in the collection date back to the 3rd millennium BC. The heroes of the ancient creation were Gilgamesh himself and his best friend, Enkidu.

The name of the hero is also found in the Tummal inscriptions - a chronicle of the reconstruction of the city of Tummal, which took place in the 2nd millennium BC. The inscriptions claim that Gilgamesh rebuilt the temple of the goddess Ninlil, which was damaged by the flood.

The mythology dedicated to the Sumerian ruler was reflected in the “Book of Giants,” which was included in the Qumran manuscripts. The manuscripts briefly touch on the king of Uruk, without focusing on the man’s exploits.

Written evidence and analysis of the work of Sumerian masters suggest that the character of the ancient epic has a prototype. Scientists are confident that the image of the ancient hero is copied from the real-life ruler of the city of Uruk, who ruled his fiefdom in the 17-16th century BC.

Myths and legends

The wayward Gilgamesh is the son of the great goddess Ninsun and the high priest of Lugalbanda. The biography of the Sumerian hero has been known since the global flood, which wiped out most of humanity from the face of the Earth. People who were saved thanks to Ziusudra began to build new cities.

Due to the growth in the number of settlements, the influence of Aggi, the last of the rulers of Sumer, began to decline. Therefore, when the matured Gilgamesh overthrew the governor of Aggi in the city of Uruk, the ruler of Sumer sent an army to destroy the daring rebel.

Gilgamesh had already become famous among the common people as an honest ruler of the city of Kullaba, located next to Uruk. After overthrowing the local government, Gilgamesh proclaimed himself king of Uruk and united both cities with a thick wall.

Agga attacked the enemy in rage, but the brave hero did not retreat. The man gathered an army of young residents and began to defend the freedom of cities from the oppression of a greedy ruler. Despite a large army, Agga was defeated. Gilgamesh received the title of ruler of the Sumerians and moved the capital of the state to Uruk.

However, Gilgamesh was distinguished not only by his strength and determination. Because of the violent temper and inappropriate pride of the leader of the Sumerians, the gods sent Enkidu to Earth to pacify and defeat the man. But instead of fulfilling the mission entrusted to him, Enkidu joined Gilgamesh and became the best friend of the ruler of Uruk.

Together with Enkidu, the man went to the country of Huwawa, the giant who sowed death. Gilgamesh wanted to get the cedars that the huge monster grew and glorify his own name among his descendants.

The road to Huwava took a long time, but the Sumerian ruler reached the magical forest, cut down the cedars and destroyed the giant. The extracted raw materials were used to build new palaces in the capital.

Despite his proud disposition and disregard for laws, Gilgamesh respected the gods. Therefore, when the goddess of love Inanna turned to a man for help, he dropped everything and rushed to the temple glorifying the goddess.

A beautiful willow tree grew in this temple, which pleased Inanna. But among the roots of the tree there was a snake. The demon hollowed out a shelter for herself in the willow trunk, and a bloodthirsty eagle built a nest in the crown.

The hero cut off the snake's head with one blow. Seeing the cruel reprisal, the eagle flew away, and Lilith disappeared into the air. Grateful Inanna gave Gilgamesh a piece of wood from which the carpenters made a magic drum. As soon as the ruler of Uruk struck a musical instrument, all the young men rushed to carry out orders, and the girls without hesitation surrendered to the power of Gilgamesh.

The contented man spent a lot of time in lovemaking, until the gods, who were tired of listening to the complaints of grooms left without brides, took away the magic instrument from Gilgamesh.

Seeing how his friend suffered from the loss of his favorite toy, Enkidu went to the underworld, where the gods transferred the magic drum. But the man did not take into account that only a person who does not break the rules can get out of the underworld. Alas, Enkidu found the drum, but was unable to leave the kingdom of the dead to return it.

Another legend tells the death of Gilgamesh's friend in a different way. The goddess, impressed by Gilgamesh's appearance and courage, invited the hero to marry her. But Gilgamesh refused the beauty, because he knew that Ishtar was not constancy.

The offended goddess complained to the god Anu, who sent a monster to Uruk. A huge celestial bull descended to Earth to destroy his beloved city. Then Enkidu rushed at the enemy, and Gilgamesh soon arrived to help. Together the men defeated the dangerous beast.

But for the massacre of the heavenly bull, the gods decided to punish Gilgamesh. After much debate, it was decided to leave the ruler of Uruk alive and take the life of Enkidu. Prayers and requests could not delay the man’s death. After 13 days, Gilgamesh's best friend died. Having mourned his comrade, the king of Uruk erected a beautiful monument in honor of Enkidu.

Saddened by the loss, the man realized that one day he too would die. Such a turn did not suit the wayward Gilgamesh, so the hero set off on a dangerous journey to meet Utnapishtim. In search of immortality, the hero overcame many obstacles. Having found a wise old man, the hero found out that eternal life is given by advice-grass that grows at the bottom of the sea.

The news did not cool Gilgamesh's ardor. Having tied stones to his feet, the man took out the magic herb. But while the hero was putting his own clothes in order, a snake dragged away the council-grass. Frustrated, Gilgamesh traveled back to Uruk to live a life of adventure and inevitably die.

- The meaning of the name "Gilgamesh" is the ancestor of the hero. Researchers claim that the word sounded like “Bilga-mas” in the Sumerian manner. And the version that has become widespread is a late variation from Akkadia.

- The character became part of the multi-part anime “Gates of Babylon”.

- Like the Bible, the stories of Gilgamesh raise the issue of the Great Flood, which destroyed many people. There is a theory that the biblical catastrophe was borrowed from the Sumerians.

Quotes

“Here in Uruk I am the king. I walk the streets alone, for there is no one who dares to come too close to me.”

“Enkidu, my friend, whom I loved so much, with whom we shared all our labors, he suffered the fate of a man!”

“I will chop cedar, - the mountains will grow over it, - I will create an eternal name for myself!”

“After wandering around the world, is there enough peace in the land?”

“Let your eyes be filled with sunlight: darkness is empty, as light is needed!”